- 381 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

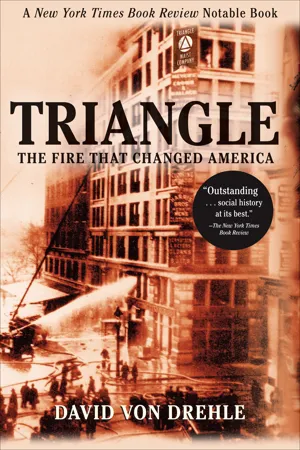

This "outstanding history"

of the 1911 disaster that changed the course of 20th-century politics and labor relations "is social history at its best" (Kevin Baker,

The New York Times Book Review).

New York City, 1911. As the workday was about to end, a fire broke out in the Triangle shirtwaist factory of Greenwich Village. Within minutes it consumed the building's upper three stories. Firemen were powerless to rescue those trapped inside: their ladders simply weren't tall enough. People on the street watched in horror as desperate workers jumped to their deaths.

Triangle is both a harrowing chronicle of the Triangle shirtwaist fire and a vibrant portrait of an era. It follows the waves of Jewish and Italian immigration that supplied New York City's garment factories with cheap, mostly female labor. It portrays the Dickensian work conditions that led to a massive waist-worker's strike in which an unlikely coalition of socialists, socialites, and suffragettes took on bosses, police, and magistrates. And it shows how a public outcry over the fire led to an unprecedented alliance between labor reformers and Tammany Hall politicians.

With a memorable cast of characters, including J.P. Morgan's blue-blooded activist daughter Anne, and political king maker Charles F. Murphy, as well as the many workers who lost their lives in the fire, Triangle presents a dramatic account of early 20th century New York and the events that gave rise to urban liberalism.

A New York Times Book Review Notable Book

New York City, 1911. As the workday was about to end, a fire broke out in the Triangle shirtwaist factory of Greenwich Village. Within minutes it consumed the building's upper three stories. Firemen were powerless to rescue those trapped inside: their ladders simply weren't tall enough. People on the street watched in horror as desperate workers jumped to their deaths.

Triangle is both a harrowing chronicle of the Triangle shirtwaist fire and a vibrant portrait of an era. It follows the waves of Jewish and Italian immigration that supplied New York City's garment factories with cheap, mostly female labor. It portrays the Dickensian work conditions that led to a massive waist-worker's strike in which an unlikely coalition of socialists, socialites, and suffragettes took on bosses, police, and magistrates. And it shows how a public outcry over the fire led to an unprecedented alliance between labor reformers and Tammany Hall politicians.

With a memorable cast of characters, including J.P. Morgan's blue-blooded activist daughter Anne, and political king maker Charles F. Murphy, as well as the many workers who lost their lives in the fire, Triangle presents a dramatic account of early 20th century New York and the events that gave rise to urban liberalism.

A New York Times Book Review Notable Book

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Triangle by David von Drehle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

SPIRIT OF THE AGE

Burglary was the usual occupation of Lawrence Ferrone, also known as Charles Rose. He had twice done time for that offense in New York state prisons. But Charley Rose was not a finicky man. He worked where there was money to be made. On September 10, 1909, a Friday evening, Rose was employed on a mission that would make many men squeamish. He had been hired to beat up a young woman. Her offense: leading a strike at a blouse-making factory off Fifth Avenue, just north of Washington Square in Manhattan.

He spotted his mark as she left the picket line. Clara Lemlich was small, no more than five feet tall, but solidly built. She looked like a teenager, with her soft round face and blazing eyes, but in fact Lemlich was in her early twenties. She had curly hair that she wore pulled tight in the back and sharply parted on the right, in the rather masculine style that was popular among the fiery women and girls of the socialist movement. Some of Clara’s comrades—Pauline Newman and Fania Cohn, for example, tireless labor organizers in the blouse and the underwear factories, respectively—wore their hair trimmed so short and plain that they could almost pass for yeshiva boys. These young women often wore neckties with their white blouses, as if to underline the fact that they were operating in a man’s world. Men had the vote; men owned the shops and hired the sometimes leering, pinching foremen; men ran the unions and the political parties. At night school, in the English classes designed for immigrants like Clara Lemlich, male students learned to translate such sentences as “I read the book,” while female students translated, “I wash the dishes.” Clara and her sisters wanted to change that. They wanted to change almost everything.

Lemlich was headed downtown, toward the crowded, teeming immigrant precincts of the Lower East Side, but it is not likely that she was headed home. Her destination was probably the union hall, or a Marxist theory class, or the library. She was a model of a new sort of woman, hungry for opportunity and education and even equality; willing to fight the battles and pay the price to achieve it. As Charley Rose fell into step behind her—this small young woman hurrying along, dressed in masculine style after a day on a picket line—the strong arm perhaps rationalized that her radical behavior, her attempts to bend the existing shape and order of the world, her unwillingness to do what had always been done, was precisely the reason why she should be beaten.

Lemlich worked as a draper at Louis Leiserson’s waist factory—women’s blouses were known as “shirtwaists” in those days, or simply as “waists.” Draping was a highly skilled job, almost like sculpting. Clara could translate the ideas of a blouse designer into actual garments by cutting and molding pieces on a tailor’s dummy. In a sense, her work and her activism were the same: both involved taking ideas and making them tangible. And the work paid well, by factory standards, but pay alone did not satisfy Clara. She found the routine humiliations of factory life almost unbearable. Workers in the waist factories, she once said, were trailed to the bathroom and hustled back to work; they were constantly shortchanged on their pay and mocked when they complained; the owners shaved minutes off each end of the lunch hour and even “fixed” the time clocks to stretch the workday. “The hissing of the machines, the yelling of the foreman, made life unbearable,” Lemlich later recalled. And at the end of each day, the factory workers had to line up at a single unlocked exit to be “searched like thieves,” just to prevent pilferage of a blouse or a bit of lace.

With a handful of other young women, Clara Lemlich joined the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) in 1906. She and some of her fellow workers formed Local 25 to serve the mostly female waist makers and dressmakers; by the end of that year, they had signed up thirty-five or forty members—roughly one in a thousand eligible workers. And yet this small start represented a brazen stride by women into union business. The men who ran the ILGWU, which was young and struggling itself, composed mainly of male cloak makers, did little to support Local 25. Most men saw women as unreliable soldiers in the labor movement, willing to work for lower wages and destined to leave the shops as soon as they found husbands. Some men even “viewed women as competitors, and often plotted to drive them from the industry,” according to historian Carolyn Daniel McCreesh. This left the women of Local 25 to make their own way, with encouragement from a group of well-to-do activists called the Women’s Trade Union League.

The Leiserson’s strike was Lemlich’s third in as many years. Using her gifts with a needle as an entrée, Lemlich “zigzagg[ed] between small shops, stirring up trouble,” as biographer Annelise Orleck put it. She was “an organizer and an agitator, first, last and always.” In 1907, Lemlich led a ten-week wildcat strike at Weisen & Goldstein’s waist shop, protesting the company’s relentless insistence on ever-faster production. She led a walkout at the Gotham waist factory in 1908, complaining that the owners were firing better-paid men and replacing them with lower-paid women. The Louis Leiserson shop was next. Did Leiserson know what he was getting when the little draper presented herself at his factory and asked, in Yiddish, for a job? Leiserson was widely known around lower Manhattan as a socialist himself, so perhaps he was complacent about agitators. More likely, he had no idea what was in store when he hired Clara Lemlich, beyond the appealing talents of a first-rate seamstress. The waist industry was booming in New York: there were more than five hundred blouse factories in the city, employing upward of forty thousand workers. It was all but impossible to keep track of one waist maker in the tidal wave of new immigrants washing into the shops.

A socialist daily newspaper, the New York Call, was a mouthpiece for the garment workers and their fledgling unions. According to the Call, late in the summer of 1909 Louis Leiserson, self-styled friend of the workers, reneged on a promise to hire only union members at his modern factory on West Seventeenth Street. Like many garment makers, Leiserson shared the Eastern European roots of much of his workforce and, like them, he started out as an overworked, underpaid greenhorn fresh off the boat. But apparently he had concluded that his promise was too expensive to keep. Leiserson secretly opened a second shop staffed with nonunion workers, and when the unionists at the first shop—mostly men—found out about this, they called a clandestine strike meeting. Clara Lemlich attended, and demanded the floor. A men’s-only strike was doomed to fail, she insisted. A walk-out must include the female workers. “Ah—then I had fire in my mouth!” Lemlich remembered years later. She moved people by sheer passion. “What did I know about trade unionism? Audacity—that was all I had. Audacity!”

She was born with it, in 1886 (some accounts say 1888), in the Ukrainian trading town of Gorodok. Clara’s father was a deeply religious man, one of about three thousand Jews in the town of ten thousand. He spent long days in prayer and studying the Torah, reading and pondering and disputing the mysteries of sacred scripture. He expected his sons to do the same with their lives. It was the job of his wife and daughters to do the worldly work that made such devotion possible. Clara’s mother ran a tiny grocery store, and Clara and her sisters were expected to help.

A memoirist once described life in a similar Russian shtetl. It “was in essence a small Jewish universe, revolving around the Jewish calendar,” he wrote, a place where a wedding celebration might go on for a week and where the Sabbath was inviolate. Twice a week, however, Clara went with her mother to the yarid, or marketplace, and there her life intersected, at least briefly, with the Russian Orthodox Christians who alone were allowed to own and farm the land.

Lemlich’s childhood corresponded with a period of enormous upheaval for Eastern European Jews, a time, as Gerald Sorin has written, “of great turmoil, but, also, [of] effervescence.” The traditions of shtetl life eroded under a wave of youthful radicalism, which erupted in response to the traumatic decline of the Russian monarchy. It was a very hard time for Russian Jews, a time of forced poverty and violent oppression, but it was also an environment where a girl could assert herself. Clara Lemlich was not content simply to work while her brothers studied and prayed. She hungered for an education. Realizing that she would have to pay for it herself, Lemlich learned to sew buttonholes and to write letters for illiterate neighbors whose children had immigrated to America. With the money she earned, she bought novels by Turgenev, Tolstoy, and Gorky, among others. But Clara’s father hated Russians and their anti-Semitic czars so deeply that he forbade the Russian language in his home. One day, he discovered a few of the girl’s books hidden under a pan in the kitchen, and he flung them into the fire.

Clara secretly bought more books.

In 1903, Lemlich and her family joined the flood of roughly two million Eastern European Jewish immigrants that entered the United States between 1881 and the end of World War I. This was one of the largest, and most influential, migrations in history—roughly a third of the Jewish population in the East left their homes for a new life, and most of them found it in America. What was distinctive about the emigration was that an entire culture pulled up stakes and moved. It was not just the poor, or the young and footloose, or the politically vanquished that left. Faced with ever more crushing oppression and escalating anti-Jewish violence, the professional classes, stripped of their positions, had reason to leave. So did parents eager to save their sons from mandatory service in the czar’s army; so did the idealists frustrated by backsliding conditions, as did the luftmenschen, the unskilled poor who had no clear way of supporting themselves in a harsh land. Although most of the arrivals in America were met by severe poverty, they kept coming. If their numbers were averaged, they arrived at the rate of almost two hundred per day, every day, for thirty years. They made a life and built a world with their own newspapers, theaters, restaurants—and radical politics.

She would not be able to run very fast in her long skirt, and was no match for a gangster. But to be on the safe side Charley Rose had recruited some help. William Lustig fell in alongside the burglar as they started down the street after Clara Lemlich. Lustig was best known as a prizefighter in the bare-knuckle bouts held in Bowery back rooms. Several other men tagged along, lesser figures from the New York underworld. In their derby hats and dark suits, they moved quickly along the sidewalk, past horse-drawn trucks creaking down the crowded avenue. With each step they narrowed the distance.

The policemen patrolling the picket line watched the gangsters set off, but did nothing to stop them. The cops weren’t surprised to see notorious hoodlums moonlighting as strikebreakers. Busting up strikes was a lucrative sideline for downtown gangsters. So-called detective agencies were constantly looking for strikebreaking contracts from worried bosses in shops where there was unrest. One typical firm, the Greater New York Detective Agency, sent letters to the leading shirt-waist factory owners in the summer of 1909, promising to “furnish trained detectives to guard life and property, and, if necessary, furnish help of all kinds, both male and female, for all trades.” In other words, this single company would—for a price—provide sewing machine operators and the brawny bodyguards needed to escort them into the factory. “Help of all kinds” might also describe the professional gangsters occasionally dispatched to beat some docility into strike leaders.

The gang’s footfalls sounded quickly on the pavement behind Clara Lemlich. When she stopped and turned, she recognized the men instantly from the picket line. The beating was quick and savage. Lemlich was left bleeding on the sidewalk, gasping for breath, her ribs broken.

Charley Rose had done his job, and no doubt he collected his pay. But Lemlich returned to the strike a martyr and a catalyst. Within days after the beating, she could be found on street corners around the garment district, brandishing her bruises and stirring up her comrades. Everywhere she went, she preached strike, strike, strike—not just for Leiserson’s but for the whole shirtwaist industry.

This violent convergence of the hired hoodlums and the indomitable Clara Lemlich was the clashing of the old against the new. From the summer of 1909 to the end of 1911, New York waist makers—young immigrants, mostly women—achieved something profound. They were a catalyst for the forces of change: the drive for women’s rights (and other civil rights), the rise of unions, and the use of activist government to address social problems. One man who grew up on New York’s Lower East Side in the 1880s remembered his mother’s desperation the day his father died. There were no government programs to help her, no pension or Social Security. Yet she knew that if she couldn’t support her children they would be taken away from her to be raised in an orphanage. So she went directly from the funeral to an umbrella factory to beg for a job. Eighteen thousand immigrants per month poured into New York City alone—and there were no public agencies to help them.

The young immigrants in the garment factories, alight with the spirit of progress, impatient with the weight of tradition, hungry for improvement in a new land and a new century, organized themselves to demand a more fair and humane society.

What begins with Clara Lemlich’s beating leads to the ravenous flames inside the Triangle Waist Company, which trapped and killed some of the hardiest strikers from the uprising Lemlich worked to inspire. Together, the strikes and the fire helped to transform the political machinery of New York City—the most powerful machine in America, Tammany Hall.

Late summer in those days was almost unbearable for the poor in New York. “It sizzles in the neighborhood of Hester Street on a sultry day,” a magazine writer summed up simply. Swampy and feverish, the heat soaked into the stone and iron of the city by day and leaked out again by night, so that it was never gone but was just ebbing and surging like a simmering tide. Heat amplified the smells, the overripe scent of sweaty humans lacking adequate plumbing, the sickly sweet pungency of baking garbage, the sour-earth odor of wet manure from the countless horses pulling the wagons of the city’s insatiable commerce.

So many people in so little space: eight hundred per acre in some city blocks. Flies were fat and brazen and everywhere, because in summer the windows and doors had to be open all the time in hopes that a breeze might find its way down the river and through the crowded streets and among the close-packed tenements and across the back of one’s neck. Along with the flies came the noise of steel wagon wheels on paving stones, the wails of babies, peddlers bellowing, the roar of elevated trains, hollering children, and the scritch-scratch and tinkle of windup phonographs.

Late summer was a season of dust and grime. Half the metropolis, it seemed, was under construction, a new tower of ten or more stories topping out every five days, competing skyscrapers racing toward the clouds, a third and then a fourth bridge stretching across the East River (where a generation earlier there had been none). The hot, damp air was full of dirt, cement powder, sawdust, and exhaust from the steam shovels.

Inside a sweltering, poorly ventilated, three-room apartment, the whole thing no more than four hundred square feet, the air never seemed to stir. It was so stifling inside the tenements that in late summer people slept on the rooftops, on the fire escapes, on concrete stoops, or in the parks. Yet the air did move. The mothers, the sisters, the wives could read the evidence written in gray on the family linens. A white tablecloth—an heirloom or a wedding present from an earlier life across the ocean—would turn dingy within a day or two beside an open window.

Then there was nothing to do but scrounge a penny from the purse and put it in the gas meter on the kitchen wall. Enough gas would flow to heat water for the laundry. Out came the washboard and up went the sleeves. Late summer was the season of exhausted women with sweat running in streams down their necks and noses, dripping from tendrils of upswept hair, women bent over steaming tubs of water to scrub the grime from the tablecloths, and from the dirty white workshirts of their husbands and sons and brothers, and from their own white aprons and their light cotton shirtwaists. Beside them, inches away, fires roared in coal stoves to heat the irons and warm the starch. Scrub. Rinse. Scrub again. Then the bluing solution, the starch, the isometric muscle strain of wringing the laundry dry. After the hot irons, a day or two later, the grime was back.

Newspapers and magazines frequently published wrenching portraits of the squalor and filth of tenement life. William Dean Howells sounded a fairly typical note in his description of a tenement basement: “My companion struck a match and held it to the cavernous mouth of an inner cellar half as large as the room we were in, where it winked and paled so soon that I had only a glimpse of the bed, with the rounded heap of bedding on it; but out of this hole, as if she had been a rat, scared from it by the light, a young girl came, rubbing her eyes and vaguely smiling, and vanished upstairs somewhere.” In 1909, there were more than one hundred thousand tenement buildings in New York City. About a third of them had no lights in the hallways, so that when a resident visited the common toilet at night it was like walking lampless in a mine. Nearly two hundred thousand rooms had no windows at all, not even to adjoining rooms. A quarter of the families on the Lower East Side lived five or more to a room. They slept on pallets, on chairs, and on doors removed from their hinges. They slept in shifts. Some, especially the women who worked all day and took home piecework from the factories at night, seemed never to sleep at all.

Somehow they kept their dignity even when they had little else, even in the most brutalizing days of summer. Howells noticed this. “They had so much courage as enabled them to keep themselves noticeably clean in an environment where I am afraid their betters would scarcely have had the heart to wash their faces and comb their hair.” A morning glory climbing a trellis outside a third-floor window; tiny rooms painted with a stencil to resemble fancy wallpaper; a starched white tablecloth as crisp and smooth as paper—with signs like these, the poor of New York asserted their humanity.

There were larger signs, too. The summer of 1909 was a season of strikes in New York’s garment district. In August, more than fifteen hundred tailors walked off the job. Then there was a brief strike by the men who ran the buttonhole machines. This activity wasn’t unusual in itself. Garment strikes had long been a regular feature of a hectic, rapidly growing industry. They were generally brief wildcat affairs, single-shop walkouts designed to grab an owner’s attention long enough to squeeze a raise out of him. But the garment industry had become quite large and had begun to mature, having doubled in size over the previous decade. By 1909 more people worked in the factories of Manhattan than in all the mills and plants of Massachusetts, and by far the largest number of them were making clothes.

After the latest in a string of economic depressions, business was once again brisk, but factory owners were slow to raise pay and improve conditions. Young workers earning “training wages” made as little as three dollars per week, barely enough to cover room and board. Even the most highly paid workers, who earned twenty dollars per week or more, had seen their wages decline with the depression. All of them had to tolerate a highly seasonal business with long idle periods of no pay at all.

This was the climate in which Clara Lemlich was operating, buoyed by the Women’s Trade Union League. It says something about the era that the league was founded by a man, William English Walling, the son of a Kentucky millionaire. As a volunteer social worker in the New York slums, Walling had noticed the legions of women going to work in factories, and heard the general contempt for them among the men who ran the unions. Inspired by the labor socialists of England, Walling created the WTUL in 1903 “to assist in the organization of women wage workers into trade unions.” A subcurrent of sexual concern also energized the league: members worried that young women of the New York slums were being forced into prostitution to support themselves and their families. This problem of “white slavery” was a frequent theme of sensational congressional hearings, sermons, and investigative journalism. Higher wages, the WTUL reckoned, would solve the problem, and the way to get higher wages was to build strong unions.

Walling quickly passed the leadership of the WTUL to women. Pioneering reformers, such as Jane Addams of Hull House and Lillian Wald of the Henry Street Settlement, served as early officers, and a young New York society woman named Eleanor Roosevelt—a niece of the president of the United States—was a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Triangle

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Prologue: Misery Lane

- 1 Spirit of the Age

- 2 The Triangle

- 3 Uprising

- 4 The Golden Land

- 5 Inferno

- 6 Three Minutes

- 7 Fallout

- 8 Reform

- 9 Trial

- Epilogue

- Appendix

- Notes

- Notes on Sources

- Selected Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- Footnote