- 366 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The acclaimed novelist's award-winning memoir of growing up in a remote Chinese fishing village is "a rich and insightful coming-of-age story"

(

Kirkus).

The acclaimed author of A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers and I Am China, Xiaolu Guo grew up an unwanted child in a poor fishing village on the East China Sea. But a Taoist monk made a startling prediction to her grandmother: that Guo would prove herself to be a peasant warrior and grow up to travel the nine continents.

In Nine Continents, Guo tells the story of a curious mind coming of age in an inhospitable country, and her determination to seek a life beyond the limits of its borders. From her family's village to a rapidly changing Beijing, to a life beyond China, Nine Continents presents a fascinating portrait of how the Cultural Revolution shaped families, and how the country's economic ambitions have given rise to great change. This "moving and often exhilarating" memoir confirms Xiaolu Guo as one of world literature's most urgent voices ( Financial Times, UK).

The acclaimed author of A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers and I Am China, Xiaolu Guo grew up an unwanted child in a poor fishing village on the East China Sea. But a Taoist monk made a startling prediction to her grandmother: that Guo would prove herself to be a peasant warrior and grow up to travel the nine continents.

In Nine Continents, Guo tells the story of a curious mind coming of age in an inhospitable country, and her determination to seek a life beyond the limits of its borders. From her family's village to a rapidly changing Beijing, to a life beyond China, Nine Continents presents a fascinating portrait of how the Cultural Revolution shaped families, and how the country's economic ambitions have given rise to great change. This "moving and often exhilarating" memoir confirms Xiaolu Guo as one of world literature's most urgent voices ( Financial Times, UK).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nine Continents by Xiaolu Guo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I | SHITANG: TALES OF THE EAST CHINA SEA

Once upon a time, there was neither East nor West. There were neither animals nor human beings. Aeons passed. Water appeared. Algae and fish grew. Plants began to root themselves on sandy shores. Birds flew from one hill to another. More aeons passed – tigers, lions, phoenix, serpents, salamanders and tiny slithering creatures all found their quarters in the jungle to hunt and rest. But still, the world was quiet, as if waiting for some momentous event, the birth of some wicked and powerful creature. One day, Heaven’s Eyes saw a piece of five-coloured stone shining on a mountain in the east. The stone kept shining until suddenly it burst into pieces and a monkey jumped out from the dust. The monkey had a handsome face, four long limbs and a slim body. He moved about in the fresh mountain air as he looked around with enormous curiosity. He then bowed to each of the four quarters of the sky, expressing gratitude for his birth.

The little monkey explored his world with gaiety. He fed on bananas and peanuts and drank from brooks and springs. He made friends with tigers and leopards, sloths and baboons. But one autumn day when the sun was going down, he suddenly felt sad and burst into tears. He raised his eyes to the risen moon in the east. He felt lonely. A great urge inside him told him to do something deserving with his life. But he didn’t know what this great task could be. He stared at the moon slipping towards the west and fell asleep. During the night, he felt a drop of dew falling on his face. Then he heard someone speaking in his ear. The voice said:

‘Little creature, you are not an ordinary monkey. You were nourished by the five elements of this planet, and have received the energy of heaven and earth from the beginning of time. You are the force of human life. You need to find the human world and to help a monk called Xuanzang to obtain the purest Buddhist scripture on earth. Once the sutra is secured, humans will achieve real knowledge of life and death.’

The monkey woke up under the moonlight, his ears still echoing with these words. Through the fragrant banana leaves, he felt a polar star shooting light right into his forehead.

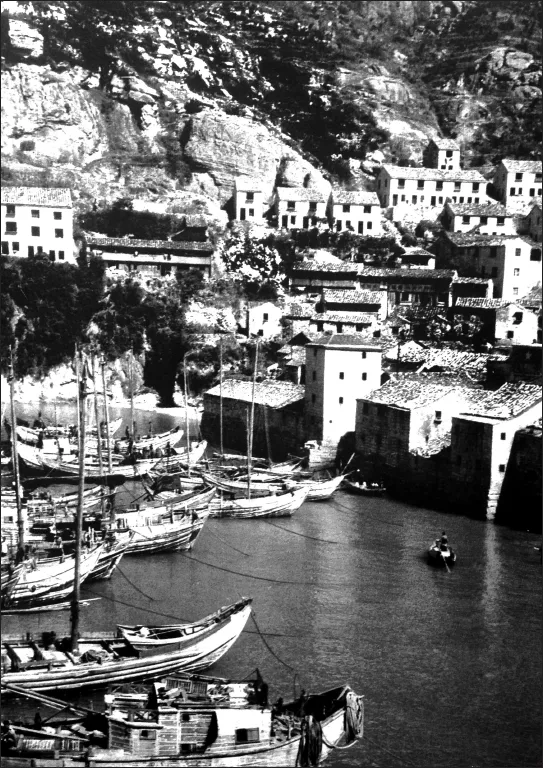

Village of Shitang, Zhejiang Province, where I spent my first seven years, 1970s

After I Was Born

I was born an orphan. Not because my parents had died, no, they were both still very much alive. Rather, they gave me away.

Of course, I don’t remember anything specific about my first two years. No one in my family does. As a newborn, I had been given to a peasant couple who lived in a mountain village somewhere in our province by the East China Sea. Many years later, I was told a story that my mother couldn’t raise me as my father had been imprisoned in a labour camp at the time. So that’s where I lived, on that mountainside, for the first two years of my life. The only memory I have is a false one, told to me by my grandparents, who recounted the day when the barren couple from the highlands brought me, the unwanted child, back down the mountain to them.

Only a baby, and already given away twice.

The couple had found out where my grandparents lived and taken the long-distance bus all the way to our humble home. The first thing they did was place me in my grandmother’s arms and say:

‘This little child will die if she continues living with us. She is dying. You can see that. We have nothing to eat. We only manage to grow fifty kilos of yam every autumn. But we need to save them to sell at the market. So we have been feeding her the mashed leaves. But every time she sees the green mush on the spoon she turns her head away, or spits it out. She refuses to eat anything green any more! You know we don’t have much rice, so the leaves are all we have. Look at her, her face is yellow and her limbs are weak. She never stops crying. She won’t eat. She won’t survive if she stays with us. So, take her back, we beg you! Take her back right now! We know we couldn’t conceive, but we don’t need a dying baby. We beg you to take her back!’

My grandparents were perplexed upon receiving me. They had nothing to say since they were not the ones who had sent me to this family in the first place. They took me without a word. From that day on, I lived with my grandparents by the sea, and my adopted parents returned to their yams, never to be heard of again. I was told later that the family bore the name Wong, that they lived on a mountain, with their yams, and apparently a few goats. Since the woman was infertile (or perhaps the man was infertile, but with peasants the woman is always to blame) she had no milk for me. I often wonder if she fed me with goat’s milk, or whether their goats produced any milk at all. In China at that time no one drank animal milk. We were all lactose-intolerant. They must have fed me with soya milk before I had teeth. What else could they have done with a starving baby whose mother had decided to give her away to a family with no milk? I will never know.

Years later, when I pored over the map of the province and tried to find the mountain village where my adopted parents might have lived, I was struck by how many there were, scattered across the country, and how many nameless places were marked only by obscure yellow and green dots. Thousands of named hamlets, and many more anonymous ones. Was it Diaotou? Pingshan? Yongjia? Hengshantou? Changshi? Shifou? I gave up. After closing the map, I was told that most of these villages had become construction sites for the expanding cities. Even the mountains had been decapitated, their peaks shaved off in order to make way for roads or quarries to provide for the country’s great development.

When I think of the first two years of my life, the image that spontaneously comes to mind is that of a small skinny goat trotting over bare mountains. Where is all the succulent grass that will satisfy her hunger? Where is the water to quench her thirst? The mountain is naked. There are only rocks and fertiliser-poisoned soil. But somehow the little goat managed to survive the impoverishment of her early life.

Grandfather

My grandfather was a bitter, failed fisherman. He was born in 1905, just one year before China’s Last Emperor Puyi was born. I don’t know if that was an ominous sign, an explanation for his fate – the last generation born under the imperial system was bound to be wiped out by new fashions. The day when he was born, his own father was apparently out at sea. In a fishing village, people say a child born while his father is at sea and the tide is rising will grow up to be a good fisherman. But the tide was receding when my grandfather emerged from his mother’s womb. He never told me this himself. Other villagers gossiped about it on benches in front of their houses. But after hearing this story, I never liked watching the tide go out.

My grandfather used to own a fishing boat, and was able to make a living from selling fish on the dock every few days. The boat was the only thing he ever cared for in his life. Nothing else mattered to him. His boat, like others in the village, was painted with two large eyes. The fishermen called them dragon eyes – a boat is a dragon that conquers the waves. The vivid colours scare away other sea creatures. Every few months, as was local practice, he would repaint the eyes a dark red, and retouch the black and blue lines along the body of the boat. From a distance, it looked like a gigantic tropical fish, with jewel-like power. Every now and then he reapplied a layer of tar, hoping that with a shiny new skin it would ride the waves like a whale. After a big catch, he let his boat bathe in the sun, fixing any broken bits, while my grandmother helped mend the fishing nets. Then he would launch the boat into the sea again, on one of those very early blue mornings. He would sail far offshore, even with limited petrol supplies. Sometimes he reached Gong Hai – the strait between mainland China and Taiwan – beyond which further navigation was forbidden. On the open water there were fewer vessels and he felt the sea belonged to him. The fish were more abundant and the eels fat and long. He would return two or three days later, sometimes quite exhausted, carrying a good catch.

In those days, no one in a Chinese fishing village would buy dead or even only half-dead fish – it was considered a bad deal. In our kitchen we cooked everything alive – preserving as much of the energy, the chi, from the sea as we could. So as the fishing boats were returning, my grandmother and the other fishermen’s wives would gather on the beach with buckets around their feet and wait. Once their husbands had hauled the boats in, the women would rush to separate the catch immediately. Shrimps went into one bucket, eels into another. Snapper were thrown into a basin of water, clams and crabs together in a large barrel, and so on. Within minutes, the fishmongers from the village markets would arrive to pick the freshest items, peeling greasy notes from their pockets. There was no need for negotiation – the prices of shrimp, crab and snapper were always the same. With eels, a delicacy in the south, prices fluctuated with the season and the difficulty of catching them.

But those were the good old days, when the villagers were free-for-all sea scavengers. Then, in the 1970s, the Communist government decided to construct the Fish Farming Collective. Individual boats like my grandfather’s were snatched away, to be ‘managed’ by the state. Fishermen were teamed together according to regional population, and then assigned a certain sector of the sea to fish in a big, industrial fishing boat. All catches belonged to the state, who would then distribute the harvest to every family according to a quota system. My grandfather was unhappy that his old way of life had been taken away, that time alone on his boat, away from the day-to-day grind and people he didn’t like. Besides, he would have had to learn industrial fishing techniques with people he had never met before, under state supervision and with everyone reporting on everyone else behind their backs. He didn’t have the character for that sort of life. He was a man born in the Qing Dynasty, the same age as our Last Emperor. For him, his days belonged to the Qing, not some quick-thinking Communist Party. So in the early 1970s, after his own boat was destroyed in a typhoon – one of those deadly storms that sweep up every summer from the South Pacific into the East China Sea – he gave up fishing. He became grumpy, spent his days drinking, and started hitting my grandmother regularly. From the age of three or four, I only really remember seeing him brooding in his room, a bottle glued to his palm.

Unfortunately, he had no other skills with which to make a living. He was starving and had virtually nothing to feed my grandmother and me. Then, one day, he found a big wooden board on a street corner. He took two benches from the kitchen and constructed a makeshift store outside our house. He would sell anything he could find – vegetables, pickled fish, shrimp paste, soap, nails and cigarettes. His cigarettes were a bit funny-looking, sold as singles, ‘treasures’ he found by the seashore. The cigarettes were originally packed tight in boxes like fancy Western biscuits. But storms and war with the Communists sunk many Taiwanese Nationalist boats and released their goods into the sea. Those ‘treasure chests’ floated ashore along with other flotsam and jetsam. And my grandfather, a proper sea scavenger, spent his days walking along the beach, picking from the goods. Somehow, he always found boxes of cigarettes, soaked through with seawater. Sometimes he would find stylish American cookies in brightly coloured tin boxes. Occasionally he would turn up with tinned food, typically beans. The cigarettes he would unpack and dry under the hot sun. He would then beautify them and sell them at a cheap price. This business worked for a while, but it depended on continued conflict in the Taiwan Strait – there wasn’t exactly a daily supply of shipwrecks in the East China Sea, and currents were also liable to take what had been wrecked further south.

Still, my grandfather managed to sustain us with these meagre pickings, if only temporarily. Every day we drank watery porridge and ate boiled kelp. Our neighbours – families of the men who had joined the collective fishing boats – would give us some extra rice and noodles every now and then. My grandfather’s scavenging days were numbered, we all knew that.

Village of Shitang

Some people said Shitang was an island, others a peninsula. It lay soaking in the salty water between mainland China and Taiwan, three hundred kilometres from the Taiwanese coast, the first place on the mainland to receive the dawn’s rays every morning. In 2000, Shitang was in the news because a ceremonial sun statue had been built on a cliff facing east. The statue didn’t look anything like the sun, but more like a tall, thin monolith out of 2001: A Space Odyssey. It turned the village into a tourist attraction. But for the people of Shitang, it was odd. They had always known their village lay furthest to the east. Why, suddenly, was it such a big deal?

Shitang literally means stone pond. The word pond in old Chinese was associated with fish. Perhaps thousands of years ago, the area had been a salt-water lagoon next to the sea, before inhabitants built up the land along the seafront, just as Hong Kong or Macau had grown up on reclaimed marsh and swamp. Our family house was a small, green-coloured stone dwelling right on the horn of the peninsula. My grandfather lived upstairs, where he could look straight out to sea through a small window by his bed. In my memory, the sea was always yellow-brown, whether seen from my grandfather’s window or from the beach. This yellow-brownness was to do with the large kelp beds growing in the shallow water by the shore. The kelp – we called it haifa, the hair of the sea – had tough stalks with broad leaf-like palms and long green-brown stripes. A swarm of shapeless sea snakes, they entangled themselves in the space between land and water. Despite its monstrous shape, we loved the taste. We either stewed it in eel soup or fried it with pork. We never tired of it, along with the tiny kelpfish we harvested from among the algae.

The soil was very salty in Shitang. It was not land suited to agriculture. There were barely any trees growing in the village. But gardenia trees are a determined species. They grew between rocks, their white flowers swirling in the salt-laden wind. It was the only type that could face the sea’s yellow foam. I loved their strongly scented flowers. Women picked the buds to tie in their plaits. One day, thirty-odd years later, I stumbled across a gardenia in northern Europe. I breathed in the familiar scent under a clear European sky and cried. This tree didn’t belong in my Western life. It was a sorrowful smell, if tinged with a warm feel of nostalgia. It took me straight back to my childhood on the typhoon-ridden coast of the East China Sea.

In that house, only my grandfather had a view over the kelp beds and the foamy sea. My grandmother and I lived downstairs, where the windows on two sides were blocked by our neighbour’s washing lines, dried squid and salted ribbonfish hanging from poles. I couldn’t say then whether I loved or hated that house. I lived there until I was seven. It was simply our house, our village. There was no comparison, no alternative. But years later, after I had left the village, I felt that Shitang had killed all tenderness in my heart. It had become a rock in my chest. Those hard corners, those jagged stone houses had turned me to stone too. The landscape made me merciless and aggressive.

Our street was originally called Anti-Pirates Passage. In the 1980s, the name was changed to Front Barrier Slope by the local authorities. The original name came from the Ming Dynasty. During that time, the area was under constant attack by pirates from the East Pacific, such that the local militia armed themselves with home-made guns and bombs for protection. Eventually, the village was returned into local hands. But that was four hundred years ago. It felt to me that nothing significant had happened since then, apart from when the local government replaced the Buddha posters in their offices with images of Mao. It had been a backwater, from the days of China’s dynasties until now. The only dramatic stories came from the sea, from being close to Taiwan.

In the sixties and seventies, some local fishermen and villagers tried to cross the Taiwan Strait in secret, hoping they would be rewarded by the Nationalist government with gold and farmland as promised. Some succeeded, but very often they were recaptured and punished: someone’s uncle and his brother were caught on the edge of international waters and sentenced to death. In the 1970s, no one had private radios or televisions. All n...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise for Nine Continents

- Also by Xiaolu Guo

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- The Past Is a Foreign Country

- Part I Shitang: Tales of the East China Sea

- Part II Wenling: Life in a Communist Compound

- Part IV Europe: In the Land of Nomads

- Part V In the Face of Birth and Death

- Acknowledgments

- I’ll See You in Berlin

- Back Cover