- 833 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

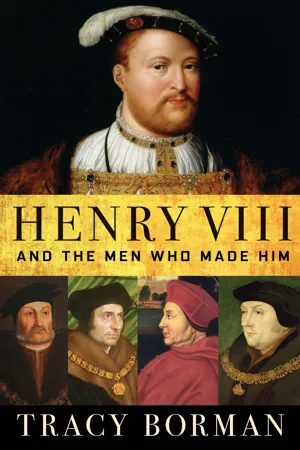

Henry VIII and the Men Who Made Him

About this book

The acclaimed historian presents a "beautifully perceptive and dynamic reassessment of Henry VIII…in this highly engrossing biography" (

Booklist, starred review).

Henry VIII is best known for his tempestuous marriages and the fates of his six wives. But his reign and reputation were hugely influenced by his confidants, ministers, and even occasional rivals—many of whom have been underplayed in previous biographies. Exploring these relationships in depth, Tracy Borman offers a fresh perspective on the legendary king, revealing surprising contradictions in his beliefs and behavior.

Henry was capable of fierce but seldom abiding loyalty, of raising men up only to destroy them later. He loved to be attended by boisterous young men like his friend Charles Brandon, who shared his passion for sport. But the king could also be diverted by men of intellect, culture, and wit, as his longstanding interplay with Cardinal Wolsey and his reluctant abandonment of Thomas More attest.

Eager to escape the shadow of his father, Henry was easily led by male advisors early in his reign. In time, though, he matured into a profoundly paranoid and ruthless king. Recounting the great Tudor's life and signal moments through the lens of his male relationships, Henry VIII and the Men Who Made Him sheds fresh light on this fascinating figure.

Henry VIII is best known for his tempestuous marriages and the fates of his six wives. But his reign and reputation were hugely influenced by his confidants, ministers, and even occasional rivals—many of whom have been underplayed in previous biographies. Exploring these relationships in depth, Tracy Borman offers a fresh perspective on the legendary king, revealing surprising contradictions in his beliefs and behavior.

Henry was capable of fierce but seldom abiding loyalty, of raising men up only to destroy them later. He loved to be attended by boisterous young men like his friend Charles Brandon, who shared his passion for sport. But the king could also be diverted by men of intellect, culture, and wit, as his longstanding interplay with Cardinal Wolsey and his reluctant abandonment of Thomas More attest.

Eager to escape the shadow of his father, Henry was easily led by male advisors early in his reign. In time, though, he matured into a profoundly paranoid and ruthless king. Recounting the great Tudor's life and signal moments through the lens of his male relationships, Henry VIII and the Men Who Made Him sheds fresh light on this fascinating figure.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Henry VIII and the Men Who Made Him by Tracy Borman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

‘The king’s second born son’

THE YEAR 1486 began with a momentous event. On 18 January, the citizens of London lined the streets in hopes of catching a glimpse of their new king, Henry VII, who had been crowned just eleven weeks before. As he made his way to Westminster Abbey once more, it was to take as his bride Elizabeth of York. Their union would mark the end of more than thirty years of bitter civil strife, in which two rival branches of the Plantagenet dynasty had battled for supremacy. Thereafter, the red rose of Lancaster would be intertwined with the white rose of York to represent a single, united dynasty: the House of Tudor.

But the marriage promised more to Henry than the end of civil war. Elizabeth of York’s blood was unquestionably royal. She was the eldest daughter of Edward IV and, with both of her younger brothers presumed dead after their disappearance in the Tower during the brief, bloody reign of her uncle Richard III, she was the most senior representative of the House of York. Although her new husband was the chief Lancastrian claimant, he could hardly boast the same pedigree. Henry’s great-grandfather had been the son of John of Gaunt (the third son of Edward III) and his long-standing mistress Katherine Swynford. The new king was thus descended from an illegitimate branch of the royal family. His father Edmund Tudor, meanwhile, had been the child of Henry V’s queen, Catherine of Valois, by her Welsh page. With such a dubious bloodline, Henry desperately needed to strengthen his right to the throne by marrying well. And the sooner he could beget an heir on his new wife, the better.

According to the humanist scholar, priest and diplomat, Polydore Vergil, who penned a history of England during his many years there, Elizabeth had been appalled by the idea of marrying the man who had usurped the York throne. ‘I will not thus be married,’ she declared, ‘but, unhappy creature that I am, will rather suffer all the torments which St Catherine is said to have endured for the love of Christ than be united with a man who is the enemy of my family.’1 If his account is true, then she soon suppressed her ‘singular aversion’. The lure of the throne must have offered a strong enticement, and Elizabeth might have reflected that it was better to marry the king than to be palmed off on one of his followers. It was not an age when women were at liberty to choose for themselves.

Besides, if his pedigree was questionable, the first Tudor king at least presented an impressive sight to his subjects. His contemporary biographer Vergil described him as ‘extremely attractive in appearance’, with a ‘slim, but well-built and strong’ figure, above the average height, and a ‘cheerful’ face, which became animated when he spoke. Francis Bacon agreed that he was of a ‘comely personage, a little above just stature, well and straight limbed, but slender’, and added that his face was ‘a little like a churchman’. He was also ‘wise and prudent’, shrewd in business and ‘not devoid of scholarship’.2 Having spent much of his adult life in exile in Brittany, Henry had honed his military skills in readiness for the day when he would launch an invasion of England and claim the crown that his indomitable mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, had always insisted was his by right. The new king had spent most of these formative years surrounded by men, his uncle Jasper Tudor foremost among them. But even though he enjoyed a reputation for piety, he had not entirely resisted the temptations on offer in Brittany and had sired a bastard son, Roland de Velville.

Although Henry was naturally reserved and introspective, which earned him the reputation of a serious and sober-minded monarch, in the company of close family and friends he was much more relaxed and convivial. Vergil describes him as ‘gracious and kind and … as attentive to his visitors as he was easy of access. His hospitality was splendidly generous.’3 The new king’s privy chamber accounts include payments to jesters, minstrels, pipers and singers. He liked to gamble and, despite his reputation as a miser, he thought nothing of waging substantial amounts on card games. He was also very fond of sport and employed two professional tennis players to help improve his game. He always took care to dress in magnificent style, anxious to project an image of majesty that might disguise his questionable claim to the throne.

Henry’s bride was no less magnificent. Aged nineteen at the time of her marriage, Elizabeth of York was nine years younger than Henry and in the full bloom of youth. She was tall like her father Edward IV and, with her lustrous blonde hair and rosebud mouth, had inherited the famed good looks of both of her parents. Elizabeth was also intelligent and a shrewd political operator, having lived her life at court. The Venetian envoy described her as ‘a very handsome woman, and of great ability’.4

Expectations were high for this union of the warring houses of York and Lancaster. ‘Everyone considers [the marriage] advantageous to the kingdom,’ observed one foreign ambassador, adding that ‘all things appear disposed towards peace’.5 But Henry looked for more from his bride than the resolution of conflict. She had to fill the royal nursery with children and thus secure the future of his fledgling Tudor dynasty.

The new queen did not disappoint. Just eight months after the wedding, she gave birth to a son, Arthur. The name was significant: Henry had displayed King Arthur’s red dragon on his banner at Bosworth, and Elizabeth’s own father had claimed descent from the legendary hero. At a stroke, Arthur’s birth rendered his father significantly more secure on his throne. Now he could boast a male heir, as well as a wife of unquestionable royal blood. His Yorkist rivals had been dealt a crushing blow.

The precious infant was soon moved to Farnham in Surrey, along with a sizeable and costly household.6 Security was of paramount importance, and the king made sure that only men of proven fidelity were chosen to care for this tiny scion of the House of Tudor. The personnel included Arthur’s wet nurse, dry nurse, yeomen, grooms and, at the head of the nursery, lady governess. The most senior official was the king’s cousin, Sir Reginald Pole, who was appointed chamberlain of the prince’s household.

The same attention to detail was applied to Arthur’s education. The respected scholar John Rede, formerly head of Winchester College, was appointed tutor and devised a classical curriculum for the infant prince. Almost from the moment that he took his first, tottering steps, Arthur also began the physical training that formed an important part of a royal heir’s education. He must be a prince in the Renaissance model, as skilled in riding and combat as he was in languages and rhetoric.

Although Elizabeth had been quick to conceive her first child, it would be more than two years before she fell pregnant again.7 In late October 1489, the queen entered her confinement at the palace of Westminster, where she herself had been born, and on 28 November she gave birth to a daughter. The arrival of a girl tended to be something of a disappointment in royal and noble families, and the London Grey Friars chronicler did not even trouble to record the infant princess’s arrival. She was christened Margaret two days later in honour of her paternal grandmother. Henry’s reaction to the birth of his daughter is not recorded. Although he must have hoped for a son to strengthen his dynasty, Margaret would still prove useful in forging an international alliance through marriage.

The queen soon assumed responsibility for the upbringing of her new daughter. This was entirely in keeping with royal tradition, whereby the male heir was groomed for kingship by specially appointed tutors and attendants, leaving the other royal children to the care of their mother. Elizabeth had been raised by her mother, Edward IV’s scandalous queen Elizabeth Woodville, so she knew what was expected of her.

As well as playing an active role in her daughter’s upbringing, Elizabeth also resumed her wifely duties shortly after the birth. Less than a year later, she was pregnant again. The child who would grow up to be England’s most famous king may have been conceived at Ewelme in Oxfordshire: Henry VII and his queen had stayed there in October 1490.8 Today, it is a picturesque village in the heart of the Chilterns, but in the late fifteenth century it was a place of some status, with strong links to the powerful de la Pole family, who were close blood relatives of the queen.

The queen’s pregnancy proceeded without incident, and she chose Greenwich as the place for her third confinement. Originally built in 1453 as ‘Bella Court’ by Humphrey Duke of Gloucester, regent to the young King Henry VI, the palace had been taken over by the king’s formidable wife, Margaret of Anjou, who renamed it ‘Placentia’ and carried out a series of substantial improvements. Soon after coming to the throne, Henry VII had enlarged the palace further, refacing the entire building with red brick and changing its name to Greenwich. Even so, the palace was considerably smaller than the other royal residences in London. But it was the queen’s favourite house. She may also have wished to retreat to the relative quiet and privacy of this, the easternmost royal palace in the capital, for her first summer birth.

There is no surviving record of when Elizabeth arrived at Greenwich, but it is likely to have been in late May or early June, when her pregnancy had entered its ninth month. Her husband was preoccupied with the threat posed by Perkin Warbeck, a young man claiming to be Richard, Duke of York, the younger of the ‘Princes in the Tower’. This second ‘pretender’ constituted a significant risk to Henry’s throne because he had secured a powerful patron in the form of Margaret of Burgundy, sister of the Yorkist king Edward IV and therefore aunt to Henry’s queen. Many in England were willing to give him credence, and the old antipathies between York and Lancaster that had torn the country apart for so many years looked set to be revived. ‘The rumour of Richard, the resuscitated duke of York, had divided nearly all England into factions, filling the minds of men with hope or fear,’ recounted Polydore Vergil.9 Deeply insecure about his right to the throne and increasingly paranoid about any rival claimants, the king was plunged into the greatest crisis of his reign so far.

What Henry needed to secure his dynasty and send a powerful message to his enemies was another son. The four-year-old Prince Arthur was thriving under the care of his tutors and household, but in this age of high infant mortality one male heir was not enough. It was therefore to his great satisfaction when news arrived that his wife had been safely delivered of a boy on 28 June. Interestingly, though, his indomitable mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, seemed to pay less attention to the birth of her new grandson than to his elder siblings. She had recorded the precise time of Arthur and Margaret’s births in her Book of Hours, but merely noted the date of this latest prince’s arrival – and even then had to correct it.10

The second Tudor prince was named after his father and baptised in the church of the Observant Franciscans, close to the palace at Greenwich. This would have pleased the king, whom Vergil noted was ‘especially attached to those Franciscan friars, known as Observants, for whom he founded many convents so that with his help this brotherhood should flourish for ever in his kingdom’.11 Even though Prince Henry was just the ‘spare heir’, his father did not stint upon the arrangements. The church was lavishly decorated with cloth of gold and damask, rich tapestries and cypress linen. A temporary wooden stage was erected, on which stood a silver font brought over from Canterbury Cathedral. The tiny prince was conveyed there, wrapped in a mantle of cloth of gold trimmed with ermine.12 Richard Fox, Bishop of Exeter and a close adviser to the king, presided over the ceremony.

If royal protocol was observed, Henry would have remained at court until he was three months old. It was at this tender age that royal babies were then established in their own household, separate from their parents. As only the second-born son, however, Prince Henry was not afforded such a privilege, and instead joined his sister Margaret at the Palace of Sheen. Their mother loved this beautiful and tranquil residence, which lay eight miles west of London. She had spent many of her own childhood years here, and it had strong associations with her own mother, to whom it had been bequeathed by Edward IV. The royal nursery was a predominantly female environment, supervised by the queen. Elizabeth’s gentle and affectionate nature formed a welcome contrast to the prince’s seemingly cold and distant father, and his domineering paternal grandmother. She doted on her younger son, and he returned her love in equal measure. It is likely that young Henry learned to read and write from his mother, and there are similarities in their handwriting.13

When Henry was three years old, his mother appointed Elizabeth Denton, one of her own gentlewomen, as head of the royal nursery. However, ‘Lady Mistress’ Denton continued to draw a salary from the queen’s household, which suggests that the latter continued to spend a great deal of her time at Sheen. There was one significant male influence present almost from the moment of his birth, however, because another member of his mother’s household to whom he was introduced was her cupbearer (and illegitimate brother), Arthur Plantagenet.

With his auburn hair, athletic build and easy manner, Arthur was every inch a Yorkist. One friend described him as ‘the pleasantest man in the world’.14 He certainly enjoyed all of the pleasures on offer at court, and was particularly fond of jousting and fine wine. The same would be said of Henry in later years. Elizabeth was as keen to shape the character as she was the intellect of her younger son, and judged her half-brother to be an ideal role model. Henry soon established a close bond with his uncle, and later reflected that Arthur had been ‘the gentlest heart living’.15 Such warmth contrasts sharply with his more restrained, respectful references to his father. Their closeness would endure, with only one notable interruption, for many years to come, and Arthur would serve his nephew faithfully until the end of his days.

The queen had fallen pregnant very soon after Henry’s birth, and in June 1492 she began her fourth confinement at Sheen. This resulted in the birth of another daughter, Elizabeth, on 2 July. The event was tinged with sadness because the queen’s mother had died a few weeks before, on 8 June. The royal nursery subsequently transferred to Eltham Palace, south-east of London. Eltham had been an important royal residence for almost 200 years, and the favourite home of the queen’s father, Edward IV, who had built the magnificent great hall, which still survives today. Prince Henry would have been presented with a reminder of his maternal grandfather every time he visited the great hall because Edward’s rose en soleil emblem was carved above the entrance. Already, the one-year-old prince was beginning to physically resemble this popular Yorkist king.

Although the contemporary records include only a handful of references to Prince Henry’s early years at Eltham, they suggest that he enjoyed a very comfortable, even indulgent, upbringing. There were numerous servants to attend to his needs and those of his siblings, and for his entertainment, there was a troupe of minstrels and a fool named John Goose. It is likely that the young prince, along with his sisters, was present at the great court gatherings, which were dictated by the most important dates in the religious calendar, such as Christmas and Easter.

But Henry’s presence at such occasions was always overshadowed by that of his brother Arthur. Five years Henry’s senior and heir to their father’s throne, it was natural that the eldest prince should claim all of the attention. From a young age, it was obvious that Arthur was growing into a serious-minded young man who closely resembled his father. He excelled at his studies and was also acquiring the military prowess expected of a future monarch. The king must have been gratified to see the shaping of his son into a ruler who would emulate his own style of kingship.

Henry’s feelings towards his elder brother are not recorded. They were raised separately, and there is no evidence that they ever exchanged letters or gifts. If the younger prince harboured any resentment at being forever cast into the shadows, then he left no trace of it. Francis Bacon later recorded that, although Henry was not ‘unadorned with learning … therein he came short of his brother Arthur’.16 Such comparisons must have been irksome, but it is also possible that Henry grew to enjoy his status as the second in line, with its comparative lack of responsibility.

Bacon also paints a picture of Henry VII as a loving father: ‘Towards his children he was full of paternal affection, careful of their education, aspiring to their high advancement, regular to see that they should not want of any due honour and respect: but not greatly willing to cast any popular lustre upon them.’17 This is wide of the mark. There is little evidence that the king paid much heed to his younger son’s upbringing (or indeed that of Henry’s sisters), but he was certainly not blind to the advantages of adding to his ‘lustre’ in public. On 5 April 1493, for example, Henry granted his ‘second born son’ the office of Constable of Dover Castle and the wardenship of the Cinque Ports.18 This ceremonial post had been in existence since at least the twelfth century and carried responsibility for five strategically important coastal towns in Kent and Sussex.

An even more prestigious appointment was ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Also by Tracy Borman

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface: ‘The son was born to a greater destiny’

- Introduction: ‘The changeableness of this king’

- Chapter One: ‘The king’s second born son’

- Chapter Two: ‘Having no affection or fancy unto him’

- Chapter Three: ‘Lusty bachelors’

- Chapter Four: ‘His Majesty’s second self’

- Chapter Five: ‘The servant is not greater than his lord’

- Chapter Six: ‘Youths of evil counsel’

- Chapter Seven: ‘The most rascally beggar in the world’

- Chapter Eight: ‘The inconstantness of princes’ favour’

- Chapter Nine: ‘The man who enjoys most credit with the king’

- Chapter Ten: ‘I shall die today and you tomorrow’

- Chapter Eleven: ‘Resisting evil counsellors’

- Chapter Tweleve: ‘Every man here is for himself’

- Chapter Thirteen: ‘A goodly prince’

- Chapter Fourteen: ‘The greatest wretch ever born in England’

- Chapter Fifteen: ‘He has not been the same man’

- Chapter Sixteen: ‘My dearest son in Christ’

- Chapter Seventeen: ‘I have been young, and now am old’

- Epilogue: ‘Some special man’

- Preview: Crown & Sceptre

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Author’s note

- Bibliography

- Notes

- Index

- Picture acknowledgements

- Back Cover