![]()

1

Chief of Staff of the XIII Army Corps

The XIII Army Corps with the Fifth Army

War Breaks Out

On 1 October 1913, I was assigned as the chief of the General Staff of the XIII (Royal Württemberg) Army Corps, commanded by General of the Infantry Hermann Gustav Karl Max von Fabeck. The corps consisted of the 26th Division, commanded by Lieutenant General Wilhelm Karl Florestan Gero Crescentius, Herzog von Urach, Graf von Württemberg, and the 27th Division, commanded by Lieutenant General Friedrich Woldemar Franz, Graf von Pfeil und Klein-Ellguth. In the course of the nine months of peacetime before the war broke out I had adjusted quite well to the commanding general and to the corps General Staff. The entire staff was bound together by complete trust. Inspection trips during the winter and spring, during which I accompanied the commanding general, almost always showed a broad picture of first-class and—above all—wartime-appropriate training of all the troops and their leaders. The Württembergers are born soldiers. Differences between city and country folk are hardly noticeable. Large industrial centers in which socialist tendencies could grow were almost nonexistent in Württemberg. The entire population has a strong work ethic and is intelligent, physically tough, and productive. Class differences are not evident. Every well-educated person speaks the Swabian dialect, which is quite common among the people and which generates a bond to the Homeland and a feeling of togetherness for those from every town, no matter how small. Recognizing this characteristic in the entire population, the Württemberg Ministry of War acted wisely in reorganizing the military districts so that each division received its replacements from a specific region. That was done in anticipation of the large engagements in which the Württemberg divisions engaged. Thus, officers, noncommissioned officers, and enlisted soldiers largely knew each other from their hometowns and saw each other as comrades, which they often had been since youth. From this firm bond of camaraderie and based on my many wartime experiences with the Württembergers I concluded that among all the Germanic tribes they were the best soldiers. Not a single Württemberg unit failed during the war.

I can attest from my own experience that the war broke out as a surprise to Germany and that we did not want it. On 20 July 1914, I was granted a three-week leave, which I intended to spend with my two oldest children on the estate in Holstein that I managed for my wife’s parents. Shortly before my departure I received news of my oldest brother’s acute illness. I rushed to Berlin and soon after my arrival there I had to say farewell to him forever. Meanwhile, the news in the papers prompted me on 27 July to inquire at the Great General Staff1 as well as at the Ministry of War whether I should return to my duty station in Stuttgart. At both offices no one believed that war was imminent. Nevertheless, I also made the same inquiry to my commanding general and received instructions to continue my leave. I continued on to Holstein, but there on 29 July I received a telegram instructing me to return to Stuttgart immediately. This experience indicates to me that Germany did not want this war, but that it was forced into it by our enemies.2

Because of major delays in the rail network I did not arrive in Stuttgart until the night of 30 July. In the meantime, the corps headquarters had received orders recalling to their garrisons all troops away on exercises. The corps sent two anti-balloon guns to Friedrichshafen to protect the Zeppelin factory there. The railroad security units were already reinforced, and the railroad employees had been issued arms.

On 30 July at 1345 hours the corps headquarters received the “Imminent War Warning” order from Berlin, declaring the existence of a state of war. The order also activated the railroad security units and the replacement commands for the regional commands. In accordance with the prepared plans, the mobile units of the 53rd Infantry Brigade, which included the 1st Squadron, 19th Lancer Regiment, and the 2nd Battalion, 29th Field Artillery Regiment, called up their reservists for an exercise and proceeded to purchase horses. All the other troop units also initiated their preparations for mobilization.

On 1 August 1914 at 1808 hours the corps headquarters received the mobilization order and distributed it immediately.

On 2 August 1914 (1st mobilization day) the reinforced 53rd Infantry Brigade under the command of Major General Otto von Moser was transported to Thionville.3 The brigade consisted of the 123rd Grenadier Regiment; 124th Infantry Regiment; 2nd Squadron, 19th Lancer Regiment; and 2nd Battalion, 29th Field Artillery Regiment.

Planned and organized by the General Staff officers of the XIII Army Corps, Major Reinhardt the Ia4 and Captain von Brandenstein the Ib,5 the mobilization proceeded with no hitches. On its own initiative the corps headquarters ordered every infantry regiment and every infantry battalion to mount two to six soldiers on horseback as internal messengers. The establishment of these elements produced distinct advantages for communications and the transmission of orders within the infantry units in the environment of mobile warfare. A peculiar recommendation came in from a General Staff officer with the 27th Division in Ulm. On his own initiative, and without the knowledge of his divisional commander, he hand-carried the written recommendation to Stuttgart proposing that the additional horses acquired by the cavalry units would first have to be trained for the attack on the squadron level, and therefore the cavalry units should deploy ten to fourteen days later. After receiving a very strong counseling, the officer was sent back to his post.

The widely rumored “gold car” that was supposed to be carrying large amounts of gold from France to Russia through Germany kept the people of Württemberg in a state of great agitation. At many locations the home defense troops shot at ordinary civilian cars if they did not stop immediately upon being challenged. In Stuttgart this unfortunately resulted in the death of a brave one-year volunteer who was on his way to say farewell to his parents in Canstatt. He was shot and killed in a taxi that did not stop immediately after having been challenged.

Rumors of espionage generated unnecessary excitement among the population. At around noon on 4 August a great commotion arose right in front of my office window. When I demanded silence, I was told that just a few minutes earlier a spy who had been cutting the telegraph lines on top of the nearby main post office had been shot and killed. An officer we sent there to investigate reported back to me that everything was fine at the main post office, nobody had been on the rooftop, and not a single shot had been fired.

Transport and Deployment of the XIII Army Corps

On 6 August 1914 the transportation movements of the XIII Army Corps to Thionville began as planned. From our advance party the 1st Battalion, 124th Infantry Regiment, was sent forward to reinforce the IV Cavalry Corps (Höheres Kavallerie-Kommando 4), consisting of the 3rd and the 6th Cavalry Divisions and already in position west of the town. The lead detachment of the corps headquarters left Stuttgart on 7 August, arrived in Thionville about 1900 hours on 8 August, and went into quarters. By 11 August all the XIII Army Corps troops had unloaded in the vicinity of Thionville and were billeted according to plan. On 8 August the 13th Engineer Battalion built a bridge across the Moselle River to replace the ferry, and in the following days the unit built another bridge capable of carrying all weapons systems, including heavy artillery. All the routes to be used for the advance were reconnoitered in detail. The entire billeting was organized based on the assumption that the advance movements would proceed toward the west and northwest, but possibly also through Metz toward the south.

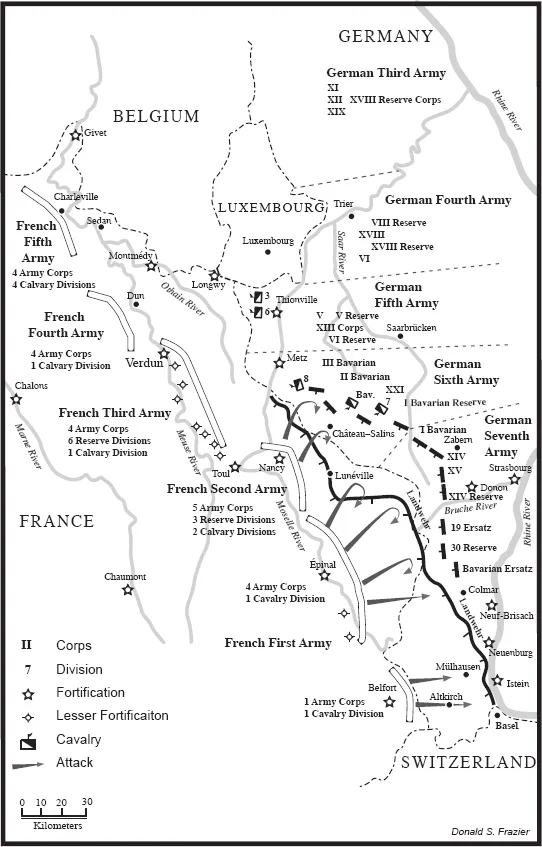

The XIII Army Corps along with the IV Cavalry Corps was assigned to the Fifth Army, which was positioned far forward northwest of Thionville.6 Initially we found only weak enemy forces at the border, and they evaded any serious contact. A French cavalry division also evaded contact. By the morning of 10 August the IV Cavalry Corps had identified on its wide front line the French 4th and 9th Cavalry Divisions and apparently two additional French corps-level cavalry regiments eastward of the Othain sector. That sector itself appeared to be occupied by infantry and artillery units. Reportedly Fortress Montmédy was occupied by infantry and possibly artillery. At the fortress at Longwy there were supposed to be two infantry regiments and horse artillery units. Ordered by Fifth Army headquarters to develop quickly a clear picture of the enemy situation beyond the front line, the IV Cavalry Corps on 10 August conducted a forced reconnaissance against the Othain sector, with the 3rd Cavalry Division to the north and the 6th Cavalry Division to the south. During the early hours of 11 August a General Staff officer from the IV Cavalry Corps arrived in Thionville and reported that the forced reconnaissance had failed, with the 6th Cavalry Division having suffered heavy losses in its Jäger battalion and its mounted artillery. The Othain sector was occupied by strong enemy infantry supported by strong field artillery and heavy artillery. The IV Cavalry Corps had been forced to withdraw, but the enemy had not pursued. The morale of the IV Cavalry Corps was low because of their failure.

In my opinion the advance elements of the IV Cavalry Corps had done their duty and had accomplished their mission of clarifying the enemy situation. I passed that opinion on to the chief of staff of the Fifth Army, Lieutenant General Konstantin Heinrich Schmidt von Knobelsdorf, whom I called immediately. After some back and forth discussion, the Fifth Army headquarters gave us permission to send a XIII Army Corps officer to the IV Cavalry Corps in order to pass on the commendation of the Fifth Army headquarters for the courageous conduct of the mission. A senior officer of the corps staff with the appropriate instructions then drove immediately to the commander of the IV Cavalry Corps, to whom he skillfully conveyed the praise. That action quickly changed the despondent morale of the IV Cavalry Corps’ leadership into one of confidence, which in turn led to the initiation of forceful action. In the evening of 12 August our staff officer returned with very encouraging—and as it later developed—accurate reports from the IV Cavalry Corps.

Those reports were also augmented with telegraphic reports from the IV Cavalry Corps. The composite reports and the reconnaissance results of the next few days gave the Fifth Army headquarters a clear picture of the opposing enemy positioned to the west. Aerial reconnaissance also provided information about the enemy’s deployments in depth. The overall picture was confirmed when the IV Cavalry Corps captured a message indicating that the entire width of the IV Cavalry Corps’ front was held by the French II Army Corps, along with the 52nd Reserve Division and elements of French VI Army Corps. The fortresses at Verdun, Longwy, and Montmédy were garrisoned and reinforced. On 14 August aerial reconnaissance reported the movement in a northwesterly direction of two enemy army corps west of Fortress Verdun. Finally, Fifth Army intelligence officers attached to the adjacent Fourth Army on our northern flank received copies of the order of battle and plans of that headquarters and its left-wing corps, which were then transmitted to the XIII Army Corps and the IV Cavalry Corps.

Map 1.

Initial Face-Off, August 1914

On 14 August at 2200 hours the Fifth Army alerted us by telephone that during the night an order would be issued for the displacement of the corps by 0800 hours on 15 August. We immediately initiated all the preparatory actions. At approximately 0300 hours that morning the order arrived, directing the strong concentration of the XIII Army Corps around Thionville, with the option of advancing either toward the west or toward the south (through Metz). We executed the order immediately. Because of the water shortages in the summer heat, the mounted troops and all of the convoys and trains were bivouacked close to the Moselle River. In the evening of 15 August a strong but short thunderstorm burst, cooling everything down.

On 16 August the troops were billeted in the town, since no order to advance had been received. That evening the commanding general of the Fifth Army, Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia, arrived in Thionville for a briefing, along with his chief of staff.

Composition, Situation, and Missions of the Fifth Army on 16 August 1914

The XVI Army Corps was positioned facing west within the extended fortifications zone of Metz, and in such a manner that it was capable of deploying toward the south on both sides of the Moselle River, or to the north.

North of the XVI Army Corps the XIII Army Corps’ reinforced 53rd Infantry Brigade had been moved forward to provide border security. To its front the IV Cavalry Corps was reconnoitering to the west. The main body of the XIII Army Corps was located around Thionville, with marching routes available to the south through Metz, or to the west.

The V Army Corps was positioned with its combat units on both sides of the Moselle. It was linked to its right with the Fourth Army’s VI Army Corps.

The V Reserve Corps was positioned behind the V Army Corps.

The VI Reserve Corps was positioned behind the XIII Army Corps.

On 16 August, the Fifth Army began displacing its headquarters forward from Saarbrücken to Thionville. The tight deployment of the Fifth Army, which was completed by 16 August, secured the options of initiating attacks to the south, the west, or the northwest. Advancing south, the XVI Army Corps, XIII Army Corps, and VI Reserve Corps proceeded as the first wave, followed by the V Army Corps and the V Reserve Corps in the second wave. An advance to the west or northwest could proceed with the V Army Corps, XIII Army Corps, and XVI Army Corps in the first wave, followed in the second wave by V Reserve Corps and VI Reserve Corps.

Until 15 August the German High Command (Oberste Heeresleitung—OHL) assessed that the main body of the French Army, with sixteen army corps, six cavalry divisions, and the associated reserve division groupings—approximately 60 percent of the total French force—was positioning for a major offensive between Metz and the Vosges Mountains, in order to force a decision in the campaign. To ensure unified planning of the German counteroffensive, all German forces in the Imperial Territories of Alsace and Lorraine (Reichsländer)7 were initially under the command of Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, commanding general of the Sixth Army. By pulling the Sixth Army back behind the Saar River, OHL planned to draw the French from Metz along the Nied River and the Saar to the Vosges Mountains, into an arch. Then we would press ahead with superior forces against both French flanks, with the Fifth Army from the north through Metz and via the Nied Position, which had been reinforced and manned with five Landwehr brigades,8 and with the mass of the Seventh Army from the east out of the Vosges Mountains. The plan also called for committing elements of the Fourth Army and reinforcing the attack front with the IX Reserve Corps, which was then located in the Nordmark,9 and including six and a half Ersatz (replacement) divisions and four Landwehr brigades.

On 16 August OHL came to the erroneous conclusion that the French main forces were no longer in Lorraine. Unfortunately, OHL then abandoned its plan for a double envelopment of the strong French forces that had been rushing into Lorraine since 14 September. If that plan had been executed, it undoubtedly would have produced a great operational victory, resulting in the destruction of major elements of the French First and Second Armies. By foregoing the operation in Lorraine by the Fourth and Fifth Armies, OHL decided to force the decision of the war by the wide envelopment through Belgium with the First through Fifth Armies, which only appeared to be opposed by inferior forces. Regrettably, the six and a half Ersatz divisions already heading toward Lorraine were not rerouted toward the German right wing.

On the German left wing the Sixth and Seventh Armies and the III Cavalry Corps were all under Crown Prince Rupprecht, who had been given the mission of securing the overall left flank of the German Army in the west. The execution of that mission was left to the crown prince’s discretion. On 16 August he ordered the start of an evasive movement by his Sixth Army, which was then in close contact with the enemy at the border. The Sixth Army was to move in the direction of the Saar River line and Saarbrücken, and then south of there in such a manner that at any time they could shift back to an offensive posture.

Considering OHL’s decision based on the events as they unfolded, it is quite clear that the operational actions of the Sixth and Seventh Armies should have been controlled by OHL on a situational basis. Only OHL could have seen clearly in the context of the overall situation how the security of the left flank of the attack front could have been executed in the most efficient manner. (The advance of the First through Fifth Armies did not start until 18 August.) Thus, for example, strong enemy pressure between the Swiss border and Metz might have resulted in the operational necessity of limiting the defense of the Nied and Saar lines and linking it into the south by holding the line Molsheim (Fortification Kaiser Wilhelm II)–Bruche River Position–Strasbourg–Neuf-Brisach–the right bank of the Rhine. Such a decision only could have been made by OHL. The ordering of other evasive actions, the establishment of new front lines from those actions, and the designation of an operational main effort for a counterattack should have been synchronized with the five attacking armies advancing in Belgium. Furthermore, a key element of OHL’s operational freedom in Lorraine was the easily available OHL reserve located there, with the six and a half Ersatz divisions. OHL also could have used that reserve initially as a follow-on force for the Fifth Army’s second echelon V Reserve Corps and VI Reserve Corps. If the V, XIII and XIV Army Corps in the lead echelon of the Fifth Army had been attacked from the south while advancing to the Meuse north of Verdun, the Fifth Army could have bent back its southern wing and then could have flanked the French attack with the V Reserve Corps and VI Reserve Corps, in conjunction with the Metz Main Reserve launching a surprise attack from the Metz fortifications.

The truth of the matter is that prior to every major decision the commander of the Sixth Army, who had been given an incredible responsibility, correctly contacted OHL, but he never received clear answers. Quite the contrary, the written and oral estimations of officers at OHL, including those by the chief of operations and the assistant chief of staff, were so far apart that the accomplishment of Crown Prince Rupprecht’s mission was not made any easier—in fact it was made extremely more difficult.

Thus, Rupprecht soon gave up on his decision to divert his movement toward the Saar, under the assumption that the French wanted to tie him down with numerically inferior forces. Intending to force a resolution of the situation, he decided on the evening of 19 August to attack. It was a frontal assault against numerically superior enemy forces, and even through it ended in a tactical victory, it cost a great deal of blood. It would have been possible to achieve an operational victory that could have destroyed the enemy only if the French had been allowed initially to move deeply into German-held territory. At that point an attack massing on both wings could have choked them off. After such a victory, which would have had ...