![]()

1

Nakhon Phanom

It was with great anticipation that the people of the United States heralded the “Agreement in Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam”—the so-called cease-fire agreement. Most Americans, myself included, thought that this agreement was the prelude to a stable and lasting peace. I, for one, tried to put the Vietnam War out of mind. The newspapers and television journalists would occasionally cover stories concerning the continuing conflict between the South and North Vietnamese; however, the extent of the ongoing cease-fire violations did not fully register with me. So, in the late summer of 1973 when I was made USSAG deputy commander, to be stationed at the Royal Thai Nakhon Phanom Airbase in northeast Thailand, the successor to the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV), which had the responsibility for supervising U.S. contributions to the wars, I had to get up to speed on the situation in Southeast Asia.

I received a thorough joint staff briefing at the Pentagon; this included the situations in Cambodia, South Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand as well as North Vietnamese logistics. There were also operations and air force briefings and a joint conference at the state department with the assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific Affairs and others.

At my Pentagon briefings I learned of two subjects that required looking into. One, Cambodians were apparently utilizing too much artillery with respect to the funding authorizations, an indication that the Pentagon was already concerned about the adequacy of Southeast Asia funding. Two, the North Vietnamese were stating that the South Vietnamese were habitually violating the cease-fire agreement. A recent Senate Foreign Relations Committee staff study noted: “Lack of respect for the Agreement is so widespread that it is impossible to apportion responsibility for the continued fighting.” Which side was initiating the armed conflicts? For propaganda purposes, in their regular weekly news conferences the Viet Cong (VC) always brought up the subject of South Vietnam’s cease-fire violations. For example, as late as 20 August 1974, Col. Vo Dong Giang, deputy chief of the VC military delegation to the Two-Party Joint Military Commission, said, “It was obvious that the U.S. Government continues to help Thieu to prolong the war of aggression against South Vietnam.” He claimed that from 16–20 August 1974, the Saigon government had committed four thousand cease-fire violations—including 664 land-grabbing operations, 2,593 police and pacification operations, 219 shellings, and 216 bombings, and reconnaissance—bringing the total number of violations since January 1973 up to 428,165.1 By any type of reckoning, this was an amazing number of cease-fire violations, and it clearly showed that the war had never ended. The cease-fire agreement prohibited all acts of force and hostile acts; both sides were to avoid armed conflict and refrain from using the territory of Cambodia and Laos to encroach upon the security of one another. North Vietnam blatantly violated almost all aspects of the cease-fire agreement.

When the cease-fire agreement was signed on 28 January 1973, and U.S. combat forces were evacuated from South Vietnam, many of the responsibilities of MACV were assigned to the USSAG, which was joined with the U.S. Seventh Air Force (USSAG/7AF). It was a multiservice integrated staff established under a U.S. Air Force commander with a U.S. Army deputy. Our headquarters was under the operational control of the commander in chief of the Pacific (CINCPAC), and its mission3 was five-fold: to plan for the resumption of an effective air campaign in Southeast Asia; to establish and maintain liaison with South Vietnamese armed forces (RVNAF) joint general staff (JGS); to exercise command over the Chief, Defense Resource Support, and Termination Office, Saigon, usually known as the Defense Attaché Office (DAO); to exercise operational control of all U.S. forces and military agencies that might be assigned for the accomplishment of its mission (this occurred for the evacuations of Phnom Penh and Saigon and the recovery of the Mayaguez); and to supervise the Joint Casualty and Resolution Center activities, resolving the status of those dedicated servicemen who were missing in action.4

The Little Pentagon

Headquarters USSAG/7AF was established in northeast Thailand at the Royal Thai Air Force Base, a few miles west of the Mekong River town of Nakhon Phanom, slightly north of the parallel delineating the Vietnam demilitarized zone. During its participation in South Vietnam, the United States had constructed a modern facility with the most advanced computer and electronic capabilities for the purpose of monitoring the millions of electronic intrusion devices placed below the demilitarized zone to detect North Vietnamese infiltration. This large, windowless building was dubbed the “Little Pentagon.” With its communications, it was tailor-made to control air force units stationed in Thailand—which in January 1973 were supporting the Cambodian armed forces (FANK) with close air support—and, in fact, was the primary reason FANK could withstand the communist attack on Phnom Penh that summer. However, on 15 August 1973 Congress passed a law terminating all combat air operations in Southeast Asia.5 There remained, however, the important aerial reconnaissance missions and search and rescue operations in Southeast Asia and adjacent waters, the former being conducted to provide indicators of communist intentions and capabilities. In compliance with the peace agreement, unarmed aircraft carried out these aerial reconnaissance activities, which were essential for providing intelligence.

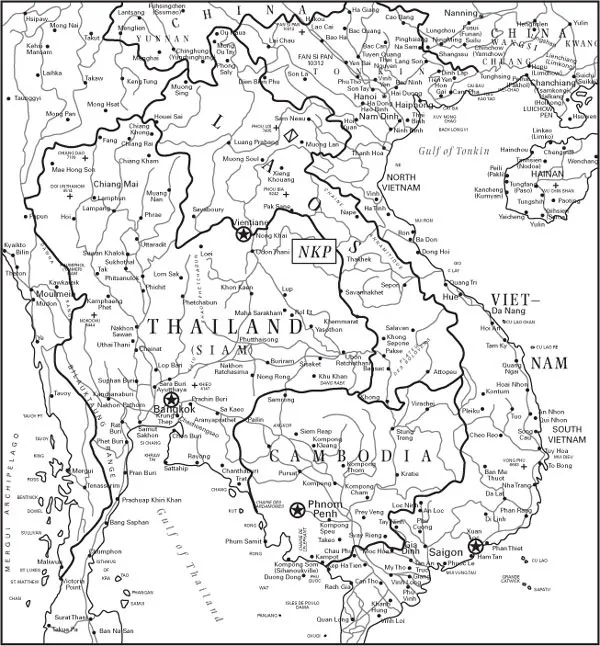

Nakhon Phanom

The Royal Thai Air Force Base at Nakhon Phanom (NKP) was a busy airfield. The U.S. Air Force had several squadrons stationed there, and, of course, there was also Headquarters USSAG/7AF. Nakhon Phanom was a hotbed of activity—50 percent of the population favored North Vietnam. The only landmark, located in the town center, was the Ho Chi Minh Tower, a clock tower donated by North Vietnam. Nakhon Phanom was located across the Mekong River from the Laotian town of Thakhek. Located in Thailand in juxtaposition to Laos with responsibilities in Cambodia and South Vietnam, Headquarters USSAG was totally involved in Southeast Asia (see map 1). I looked forward to this assignment, having served in South Vietnam before. When I was division chief of staff, the Thai component in the Vietnam War, the Queen’s Cobra infantry regiment, was attached to the unit, and its liaison officer, Major Narong, whom I had seen almost daily, was now a member of the ruling triumvirate in Thailand. I was also very familiar with the Vietnamese JGS. Brig. Gen. Tran Dinh Tho, the J-3, was a very good friend. So I wasted no time in getting to NKP. The USSAG commander, U.S. Air Force (USAF) General Timothy O’Keefe, was one of the finest officers I ever met. At the time there were ten general or flag officers assigned, and we had over 425 personnel—more than 350 assigned to USSAG and about seventy-five assigned to the Seventh Air Force. The airbase was a restricted area, requiring clearance to visit, so there were few interruptions—our headquarters was focused.

Map 1. Southeast Asia. (Source: Headquarters USSAG, Nakhon Phanom, Thailand.)

![]()

2

South Vietnam

The Defense Attaché Office

The U.S. military assistance objectives in the Republic of Vietnam, to be carried out by the DAO, were to “help to achieve and maintain the stable balanced conditions necessary to ensure peace in Indochina and Southeast Asia; assist in the development of an increasingly effective government responsive to the South Vietnamese people’s needs and wishes; support a balanced Republic of Vietnam armed force of sufficient size, strength, and professionalism to counter the principal threat facing South Vietnam; and contribute to the healing of the wounds of war and the postwar reconstruction and rehabilitation of South Vietnam.”6

Unquestionably, these objectives were related to circumstances well beyond U.S. control. Obviously, when they were made public, the Pentagon envisioned that the Vietnamese parties would undertake to maintain the cease-fire and ensure a lasting and stable peace, not a de facto state of war. In reality, the military assistance objectives boiled down to just one: to support balanced Republic of Vietnam armed forces. That support depended directly upon the receipt of sufficient congressionally approved funding to ensure the maintenance and replacement of essential military equipment and to procure necessary supplies, particularly ammunition and petroleum, to enable the country to counter the North Vietnamese threat.

To provide that support was a huge undertaking; consequently the DAO was a major operation. Not only did it support the 1.1 million-man RVNAF, but it had to provide housekeeping activities for the approximately sixty-five hundred U.S. personnel associated with the mission. There were about four thousand direct-hire and contract employees and twenty-five hundred U.S. citizen dependents. Additionally, the total local national workforce exceeded twenty thousand personnel. The DAO had personnel scattered throughout South Vietnam, but its main effort was in a compound at Tan Son Nhut Air Force Base in Saigon.7

The DAO’s internal budget was about $40 million, and it had an authorized strength of about 940 personnel. It was a huge, busy organization. Maj. Gen. John Murray was the first defense attaché and was succeeded by Maj. Gen. Homer Smith in September 1974. Both were extremely competent managers and outstanding logisticians. The DAO people were dedicated, hard-working personnel and they provided superior support to the RVNAF.

Vietnam Update

I knew that to properly assess the situation in South Vietnam in 1973 I needed to analyze the capabilities of both the South and North Vietnamese armed forces. It was also essential that I learn how the military situation had changed since I had left South Vietnam in 1969—particularly with respect to the Vietnamization program and the major 1972 all-out North Vietnamese Army (NVA) Easter campaign. What follows, then, is an update on friendly and communist capabilities: their relative manpower; the North Vietnamese infiltration of supplies and equipment; a review of the South Vietnamese Air Force, Navy, and Army armor and artillery capabilities; and the key U.S. funding situation, to include the effects of the worldwide oil-induced inflation on South Vietnam. Only after understanding these elements could I answer the important question “How does the RVNAF stack up against the NVA/VC?”

The NVA/VC

Historical Perspective

In late 1973, the intelligence section of the South Vietnamese joint general staff (J-2) produced a study entitled “Communists’ Assessment of the RVNAF.”8 In wartime, it is always important to know the enemy, and this enemy’s perceptions of the RVNAF were crucial for our understanding of enemy tactics. Although intelligence-gathering necessarily includes considering all sources of inputs, the J-2 study relied primarily on official enemy reports and assessment records on the spirit and combat capabilities of the RVNAF published by communist technical agencies, which were very difficult to acquire because they were classified as VN ABSOLUTE SECRET. However, since there were continuous leaks of important classified information from both sides throughout the conflict, this material was often available.

This study summarized a historical perspective of the Vietnam conflict as well as the enemy’s view of our allies. The North Vietnamese analysis divided the war into eight different periods, commencing with the 1954 post–Geneva Accord political struggle and continuing through the 1973 post-cease-fire episode. The NVA called its 1972 episode “The Period of Ending the War,” and it opted to launch a spring-summer campaign, hoping to shatter the Vietnamization plan and pave the way to ending the war. In the post-cease-fire episode, it regarded the political struggle as its primary stratagem and armed attacks as its supporting means. It estimated the Vietnamese armed forces would be “utterly confused” at the initiation of the cease-fire and it intended to exploit the situation to grab more land and gain a larger population.

After its historical review, the J-2 study continued to compare the communists’ assessments of their opponents in specific areas such as organization, equipment, and combat capabilities.8 With respect to combat capabilities, the communists viewed the South Vietnamese strengths the same as did the DAO’s enemy capabilities versus RVNAF potential review—that is, their strengths were in air and artillery firepower, greater mobility, ability to reinforce the battlefield, and effective logistical support. Thus, the North Vietnamese were well aware of the South’s strengths, and with respect to their own shortcomings they had drawn valuable lessons from their mostly failed 1972 campaign.

The North Vietnamese thought the RVNAF overemphasized tactics based on using modern equipment, resulting in reliance on strong firepower instead of infantry to conduct assaults. They stated that the army often deployed in circle formations rather than defense-in-depth, and consequently their formations could be easily broken. They saw a lack of coordination between mobile units and main attacking units.

The North Vietnamese Army was oriented offensively, both tactically and strategically. To the NVA, the defense was a transitory phase to be used to rebuild, reorganize, and refit resources. These assessments originated in the North Vietnamese’s offensive operational viewpoint: they saw the RVNAF as a basically vulnerable, defensive, reaction-oriented force. In sum, the communists thought the allied forces relied too much on modern weapons and overlooked the individual fighting spirit.

Notwithstanding this high-level assessment, debriefs of prisoners of war and ralliers (those enemy who surrendered to the GVN) in November 1973 revealed several positives concerning the capabilities of the individual South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) soldiers. One prisoner of war “considers the average ARVN soldier to be daring and dedicated.” Another who had fought in two engagements with ARVN stated he found “enemy troops to be spirited fighters.” An enemy lieutenant from the political staff of Military Region 3 (MR-3) “considers ARVN … now superior to the communists in both spirit and equipment.” A source from MR-4 thought “ARVN’s use of firepower strong and logistics to be superior to the Communists.”9

One sunny day I visited one of the RVNAF hospitals. It was hot, and there was no air-conditioning. The patients were dressed only in boxer shorts, bare from the waist up. I stopped to chat with a wounded army noncommissioned officer. I could see several ugly scars on his torso from previous wounds. He told me he had been fighting for seven years and had been wounded five times, yet he was anxious to return to his unit and the war. Considering the length and brutality of the war, the spirit and courage of South Vietnamese soldiers was compelling. Many of the North Vietnamese combatants had been far from home for as long as four or five years. For all involved it was a long war.

The North Vietnamese Army initiated its all-out 1972 Easter Offensive on 30 March 1972, and it culminated by the end of the dry season in late June and early July. The communists launched major attacks on three fronts. At the demilitarized zone, they initially committed three divisions supported by tanks and heavy artillery to seize Quang Tri Province and Hue. Ultimately, eight divisions and fifteen separate armor, artillery, infantry, and sapper regiments were employed. In the central h...