![]()

I

The Code and the Censors

A scene from Cecil B. DeMille’s Sign of the Cross, a film that outraged the Catholic clergy and helped to establish the Legion of Decency and strengthen the Production Code. (Courtesy of Photofest.)

![]()

1

Origins of the Code

The Motion Picture Production Code was a self-inflicted wound that took over thirty-four years to heal, affecting more than eleven thousand films, weakening most and leaving only a few stronger for the encounter.

The origins of the Production Code were grounded in a 1915 Supreme Court decision that motion pictures were “a business pure and simple,” and thus not protected speech under the Constitution. This decision paved the way for censors at all levels, and by 1921 five states—Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maryland, Kansas, and New York—had established censorship boards to assuage growing fears that the immorality emanating from Hollywood might infect society at large. These states, which controlled nearly 30 percent of the ticket sales in the United States, had the power to ban individual films or snip selected scenes at will. They wielded this power with little oversight or consistency. Women could not smoke onscreen in Kansas, but they could in Ohio. Pregnant women could not appear on-screen in Pennsylvania, but they could in New York.1 When the New York Times asked the first chairman of New York’s Board of Censors, George H. Cobb, what principles of censorship the board followed, he replied, “So far I haven’t been able to find any.”2 A few major cities also established their own censorship boards, so that a well-traveled film could experience enough cuts to render it incoherent.

Fearing that they might eventually have to march to the tune of forty-eight different state drummers, and possibly follow a conductor at the federal level, the studio heads countered the move to state censorship boards early in 1922 by forming the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA—the forerunner of today’s Motion Picture Association of America). To lead the MPPDA, the studio heads selected Will Hays, who had successfully run Warren G. Harding’s 1920 presidential campaign and been rewarded with the job of postmaster general. The studio heads, who were predominately Jewish, understood that in 1920s America they needed a front man like Hays, “folksy and Protestant, a Republican from Indiana, who could speak the language of the American heartland.”3 Hays’s primary jobs were to stem the rising tide of state and local censorship boards and to improve the public image of the movie industry.

Hays succeeded admirably at the first of these jobs. Of the thirty-seven states with censorship bills pending before he took over as head of the MPPDA, only one, Virginia, succeeded in creating a censorship board. In Massachusetts, the bill to create such a board passed the state legislature but needed the approval of a public referendum to become law. Prior to the referendum in November 1922, Hays sent lobbyists to small-town papers and encouraged exhibitors to screen slides between movies encouraging viewers to vote against the censorship proposal. As a result, the bill was defeated by a walloping 2.5 to 1 majority.

Massachusetts eventually sidestepped the results of the vote by invoking “blue laws” that forbade immoral undertakings on the Sabbath, empowering state officials to act as censors on Sundays. Since exhibitors weren’t likely to show one version of a film on Sunday and another on the other six days of the week, Massachusetts effectively became the seventh state to create a censorship board. But the state’s overwhelming public vote against censorship was not lost on other states considering censorship legislation.

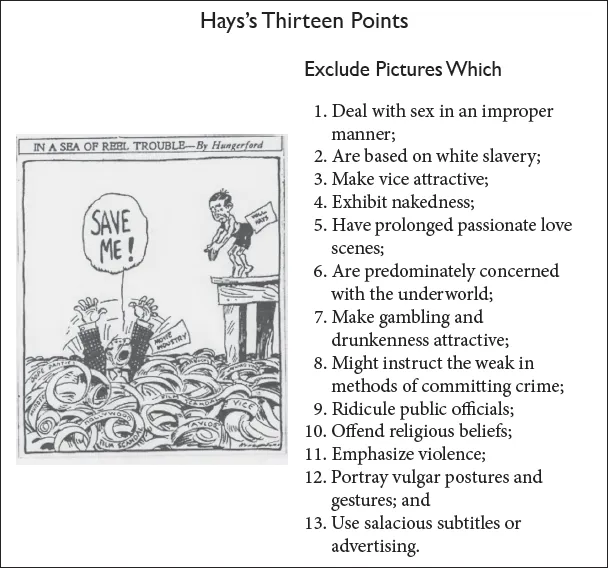

Hays attempted to polish the public face of the film industry in a number of ways. He encouraged studios to incorporate a morals clause in their actors’ contracts, hoping to avoid scandals like the Fatty Arbuckle rape trials and the William Desmond Taylor murder case, which ruined the careers of established stars in the early 1920s. To avoid future scandals, he issued what Hollywood unofficially called “The Doom Book,” a list of 117 actors deemed unfit for movie roles by reason of their personal involvement with drug use, illicit sex, or other licentious behavior.4 To convince state agencies, civic groups, and religious organizations that they didn’t have to police the industry because the industry would police itself, Hays adopted and publicized a list of thirteen screen no-nos, shown in the inset.5

Hays also created a Public Relations Committee (later the Studio Relations Committee) under Colonel Jason S. Joy to review plays and novels considered for screen adaptation and advise studios on those elements likely to offend local censor boards. However, there was no mechanism forcing studios to submit materials for review or requiring them to follow the committee’s recommendations. As a result, studios began withholding materials and ignoring the committee’s recommendations on material that they did submit.6 So, operating behind the shield of their burnished public image, the major studios quickly returned to business as usual, and films became more and more daring as the 1920s progressed. The introduction of sound in 1927 added another dimension to the movies and presented another potential avenue that could threaten public morality.

A 1922 cartoon depicting Will Hays coming to the rescue of the motion picture industry.

As films grew racier, complaints from civic groups and church organizations increased, as did threats of legislation. Sensing the need for tighter controls, Hays sent Joy to meet with the heads of state censorship boards to learn what elements were most often cut from the films they reviewed. Hays used this information to expand his list of thirteen screen no-nos to a broader program of thirty-six guidelines consisting of eleven “Don’ts” and twenty-five “Be Carefuls” (see appendix). The list of “Don’ts” included profanity, nudity, drug trafficking, sex perversion, and willful offense to any nation, race, or creed. In addition, movie makers were admonished to “be careful” when dealing with such issues as the flag, international relations, firearms, robbery, brutality, murder techniques, smuggling methods, the execution of death penalties, sympathy for criminals, sedition, cruelty to children or animals, rape, men and women in bed together, seduction, surgical operations, drug use, law enforcement, and excessive or lustful kissing.

With the revamped guidelines adopted by the MPPDA, the purview of the Studio Relations Committee was expanded from a review of potential source material to a review of scripts and finished films. But Hays’s efforts were doomed to fail. The committee’s function remained advisory, and studios were under no obligation to follow its advice. Nor were they under any obligation to submit films for review. By the close of the 1920s, barely half of the MPPDA members’ scripts were submitted for review, and only 20 percent of finished films were submitted.7 Those producers who followed the committee’s suggestions lost customers to studios offering racier fare. Universal producer Carl Laemmle complained that his company was “losing business because of its reputation for ‘namby-pamby’ movies.”8 It’s hardly surprising, then, that films continued to grow hotter and hotter. In 1929, Joan Crawford doffed her skirt for a sweaty Charleston in Our Dancing Daughters, and Renee Adoree swam nude in Mating Call.

As the movies heated up, so did cries for government oversight. In 1929, William Randolph Hearst directed his newspaper empire to push for federal censorship, and Iowa senator Smith W. Brookhart introduced a bill to place the movie industry under the direct control of the Federal Trade Commission.

Martin S. Quigley was another man who was concerned over the rampant immorality in motion pictures. A devout Catholic and publisher of film trade journals, Quigley had long editorialized against screen immorality and enlisted the aid of a Jesuit priest, Daniel J. Lord, to develop “a reliable yardstick and document of guidance to the appreciation of American mores and American decency.” Recognizing that Hays’s helterskelter lists of “Don’ts” and “Be Carefuls” were nothing more than “isolated statements, unconnected [and] in no way complete or clear,” Quigley and Lord created a code that included not only rules and regulations but a unifying philosophy.9

Their Code contained four thousand words, divided into two sections: a philosophical justification entitled “General Principles” followed by a series of guidelines called “Working Principles.” In an abbreviated addendum designed for easy consumption by studio heads, the General Principles were summarized as follows:

1. No picture should lower the moral standards of those who see it.

2. Law, natural or divine, must not be belittled, ridiculed, nor must a sentiment be created against it.

3. As far as possible, life should not be misrepresented, at least not in such a way as to place in the mind of youth false values on life.

The Code’s Working Principles contained a series of positive and negative injunctions that were far more comprehensive and logically arranged than the “Don’ts” and “Be Carefuls” of the Hays office. For example, there were specific instructions covering “Details of Plot, Episodes, and Treatment”; detailed rules regarding such plot devices as sex, passion, seduction, and murder; and extensive guidelines on such “flashpoints as vulgarity, obscenity, costume, dancing, locations, and religion.” The Code, written while Prohibition was still the law of the land, contained the provision “The use of liquor in American life, when not required by the plot or proper characterization, will not be shown,” a stipulation that continued to be observed long after Prohibition had been repealed.

Will Hays saw the Code as a godsend, and the MPPDA moguls signed onto its provisions in February 1930. This signing led historian Francis G. Couvares to observe that the movies were “an industry largely financed by Protestant bankers, operated by Jewish studio executives, and policed by Catholic bureaucrats.”10 Although the authors of the Code were indeed Catholic, the Code itself was largely nondenominational. However, the Catholic concepts of punishment and redemption did find their way into the practical interpretation of the Code. Sin could be shown on-screen, but only if the perpetrators repented or were appropriately punished.

A number of filmmakers took immediate advantage of this loophole. The early 1930s brought a rash of gangster films (Little Caesar, Public Enemy, Scarface, I Was a Fugitive from a Chain Gang) that ran roughshod over Code admonitions against brutal killings, excessive liquor use, unrestricted use of firearms, and the depiction of crimes “in such a way as to throw sympathy with the crime as against law and justice.” Gangsters were shown living well, drinking heavily, and sporting mistresses before being dispatched in a hail of bullets in the final scenes.

Cecil B. DeMille was a master at baiting the audience with a hundred minutes of titillation before offering five minutes of punishment before the closing credits. In his 1932 biblical epic, The Sign of the Cross, he filled the screen with pagan sacrifices of scantily clad Christians, Roman orgies, and Claudette Colbert naked in a bath of ass’s milk before getting around to the burning of Rome. This movie drove a wedge between Hollywood and an outraged Catholic hierarchy that perceived, not without reason, that the movie community was going about its business as if the Production Code did not exist.

And as a practical matter it didn’t, because the Studio Relations Committee, which continued to review scripts, had no real power. On the rare occasions (ten times in three and a half years following Code approval) when the committee refused to approve a film, an appeals jury would overturn its verdict. This result was hardly surprising since the jury pool consisted of three producers from competing studios who expected (and received) lenient treatment when their own films flunked the review process. So even though censorship guidelines had grown from the 385 words of Hays’s original thirteen points to nearly 4,000 words, movies kept getting hotter and hotter.

In 1932 an indifferent gangster film starring George Raft introduced the movie public to a scene-stealing sex bomb who would blight the lives of censors for the rest of the decade. Mae West was an instant sensation in the film Night After Night, and Paramount soon announced it would feature her in the film version of Diamond Lil, a stage play laden with double and single entendres she had written. One of her earlier Broadway plays, with the truth-in-advertising title Sex, had landed her in jail for ten days on charges of “obscenity and corrupting the morals of youth.” Will Hays had personally placed Diamond Lil on the Studio Relations Committee’s list of unfilmable properties.

Diamond Lil turned out to be eminently filmable, with a new title, She Done Him Wrong, and the heroine Diamond Lil renamed Lady Lou. In addition to these name changes, the Studio Relations Committee had also managed to snip a few lines of ribald dialogue, but not enough to disguise the film’s heritage or keep it from being a resounding success. As Lady Lou, Mae West still boasted that she was “one of the finest women that ever walked the streets,” and invited a young Cary Grant, acting in only his third film, to “come up sometime and see me.” She also sang songs with such suggestive titles as “A Guy What Takes His Time” and “Easy Rider.” The film clearly made hash of the Code admonitions that “impure love must not be presented as attractive and beautiful … must not be treated as material for laughter, and must not be made to seem right and permissible.” The reactions of the Code’s creators were predictable. Martin Quigley called it a “wash-out,” and Father Daniel Lord, incensed that everyone knew that She Done Him Wrong was just “the filthy Diamond Lil slipping by under a new name,” warned that “producers who decided to ‘shoot the works’ would face a ‘day of reckoning.’”11

The first of a series of Mae West Code busters.

Paramount’s day of reckoning was not quite what Lord had expected. An investment of $200,000 delivered $2 million in domestic business and another $1 million from international releases. It was almost enough to put the studio, which had been hit hard by the Depression, into the black.12 The film would also be judged an artistic success, being nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture. The studio wasted no time in capitalizing on this success, quickly releasing I’m No Angel, in which West once again invites Cary Grant, “Come up and see me,” and sneaks one of her most famous lines, “When I’m good, I’m very good, but when I’m bad, I’m better,” past the censors. Still incensed, Father Lord warned Hays that the “motion picture industry will be very unwise to incur the militant enmity of the Catholic hierarchy.”13

By 1933, increasing dissatisfaction with the perceived immorality of Hollywood films manifested itself on several fronts. Father Lord’s threat of action from the Catholic hierarchy found a voice in a New York speech by the pope’s newly appointed representative in America, Monsignor Amleto Giovanni Cicognani, in which he called for Catholic bishops and priests to undertake “a united and vigorous campaign for the purification of the cinema, which has become a deadly menace to morals.”14 This led to the formation of the Legion of Decency, which applied its own rating system to films, assigning an A to films that were morally unobjectionable, a B to films which were morally objectionable in part, and a C to condemned films. Cincinnati archbishop John McNicholas composed a membership pledge for the Legion, which read in part:

I wish to join the Legion of Decency, which condemns vile and unwholesome moving pictures. I unite with all who protest against them as a grave menace to youth, to home life, to ...