![]()

1

FLINT IS A GHOST TOWN

THE EARLY YEARS

Could secrets hidden in the history of Flint’s founding father be the source of some of the city’s troubles? Did his misdeeds leave a stain on the very fabric this city was built on?

Jacob Smith’s story starts in Quebec, where he was born in 1773 to a Canadian soap maker of German descent, John Rudolf Smith.

The memory of Jacob Smith is both obscure and romanticized. Stories abound of his deeds; some are completely fictionalized, while others hold a hint of accuracy.

Historian Kim Crawford dug deep into historical records to find the truth about Flint founder Jacob Smith. His book The Daring Trader: Jacob Smith in the Michigan Territory, 1802–1825 paints a picture of an enigma, creating as many questions as he answers, showcasing a man both self-serving and heroic. He was a man who cared deeply for the Native Americans even while helping the U.S. government take their land.

Some men claim Smith was a rascal of dubious nature; others thought him to be a very good man to know in the wilds of Michigan. Stories of his heroic actions during the War of 1812 are many. It is said he risked his own life and fortune on behalf of his adopted country and that he continued to secretly serve his country for many years after the war.

Not much can be found about his early life before leaving Quebec. Jacob married Mary Reed in 1798 and worked as a butcher before leaving Canada. Sometime between 1799 and 1801, he became a fur trader. Records show him in the Detroit area around 1800.

Smith, already fluent in French, German and English, became fluent in the Chippewa-Ottawa dialect of the Algonquin language and forged a skill of fostering positive relationships with the Native Americans. Sometime around 1811, he established a trading post at the Grand Traverse, the southernmost point of the Flint River. He was the first white citizen to farm on the Flint River, thanks to his close relationships with the Chippewa.

In 1811, Smith’s trading post alongside the Flint River was the beginning of one of the nation’s most resilient and inspiring cities. The City of Flint has enjoyed both triumph and misery. It has gone from a shining example of what the United States can be, to a tragic example of what it could become, to the icon of perseverance and pride that it is today. The city has produced heroes of commerce, business, manufacturing, solidarity, athletics, the arts, and philanthropy. Flint’s fortune has ebbed and flowed like that of its namesake and like its namesake, it is forever moving forward, unstoppable. Since 1811, Flint has been a great piece of the fabric of our nation. [Peter Hinterman, “Flint through the Decades”]

Smith fought in the War of 1812 and ingratiated himself with powerful men, like Lewis Cass, who became the territorial governor after the war ended. During the war, Smith worked as an intelligence gatherer, confidential agent and Indian interpreter-liaison. This work was unofficial yet acknowledged by Cass. Smith’s good relations with the Chippewa helped him become close to Chief Neome. The Chippewa “adopted” him and gave him the name Wahbesins, “Young Swan.” (On his gravestone in Glenwood, it is spelled “Wah-be-seens.”)

Thanks to Smith’s ties to both the native tribes and the white men in power, he played a major role in negotiating the treaty of 1819. The Saginaw Cession and Treaty ceded over six million acres of land to the U.S. government. A large piece of that land was located along the Flint River.

In addition to being on the government payroll, “Smith also carved out his own personal reward in the treaty, pulling off a real estate sleight of hand that makes all disreputable land speculators in present-day Flint look like amateurs” (Gordon Young, Tear Down, 39).

“The audacity of Jacob Smith at the Treaty of Saginaw was truly impressive. On one hand, he was acting as a secret agent on behalf of Cass to get the Chippewa and Ottawa to approve the cession of a huge portion of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula. At the same time, he was also laying groundwork for his children to claim and eventually receive thousands of acres of land by getting Indian names for them into the treaty.” (Kim Crawford, Daring Trader)

The treaty reserved large tracts of land for several white and mixed-blood Native Americans. Each was to receive 640 acres. Jacob Smith used his role as a negotiator to get portions of the land into the hands of friends and family members who were given Chippewa names, including five of his children. Some say Smith claimed that his wife, Mary, was Chippewa (Ojibwa), while many historians say she was a Canadian of Irish descent. Eventually, there were battles over the land, as many people tried to claim they were actually the Chippewa named in the treaty. Legal battles went on for years; in the end, Smith’s heirs held on to the land.

Some argue that the tribes wanted Smith to have the land, that his relationship with the tribes secured their favor: “It is safe to say, that of the 114 chiefs and head men of the Chippewa nation, whose totems were affixed to the treaty, there was not one with whom he had not dealt and to whom he had not extended some act of friendship, either dispensing the rights of hospitality at his trading post, or in substantial advances to them of bread or blankets, as their necessity required.” (F.C. Bald, Detroit’s First American Decade)

There are others who say Jacob Smith used underhanded means when negotiating the treaty, like getting the Chippewa drunk and forcing them to sign. If this is true, it really is a black mark on Flint’s history, a dark stain that seeped deep into the very foundation this city was built on. But the truth is lost in history, and what remains is highly subjective.

Author Kim Crawford’s Daring Trader digs deep into Smith’s life and finally gives us a detailed and more accurate view of Jacob Smith. But even it doesn’t give us all the answers: “Bold and controversial, self-serving and sacrificing, mercenary and patriotic, Jacob Smith served Michigan’s first two territorial governors as translator, soldier, courier and confidential agent among the Saginaw Chippewa and Ottawa Indians.”

“Smith won no battles or blazed new trails; he was not even an official party, signatory, or witness to the 1819 treaty he helped the federal government win from the Indian leaders. Yet no other fur trader in the Michigan Territory had the sort of influence he did” (Kim Crawford, Daring Trader).

Smith was a controversial figure in both life and death. He died in obscurity in 1825. None of his children came to care for him when he was sick; at the end, he was attended only by Jack, a young Indian man Smith had adopted. Several Indians attended his burial, including Chief Neome, who was filled with grief on losing his friend.

When he died, Smith left behind debt and an uncertain legacy for his heirs. Lawsuits that had plagued him in life continued to plague his heirs. He made many reckless business decisions and had a stack of unpaid debts. The land he won for his children in the treaty was disputed, and their resolution of the dispute dragged through the courts for decades.

After Smith died, his son-in-law Chauncey S. Payne came and removed all his belongings from the cabin and left it abandoned. Smith’s estate was divided up and given to his creditors to pay his debts. Flint’s first permanent structure, built by Flint’s first speculator and failed businessman, became its first abandoned building.

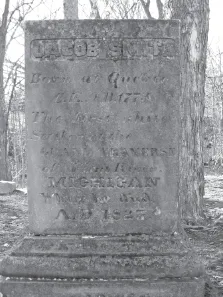

Smith was buried on his land next to his cabin by Baptiste Cochios, a mixed-blood trader. Smith was later reburied in Glenwood Cemetery with his daughters and sons-in-law, the Stocktons and Paynes.

The site where Smith’s cabin stood is now a recognized State of Michigan historical marker. It is located near the corner of West First Avenue and Lyon Avenue in Carriage Town.

In 1873, Smith’s daughter Louisa Payne and her husband, Chauncey, donated the site to the First Baptist Church of Flint. She had received the land through the treaty. The First Baptist Church resided on the site from 1873 to 1889.

Around 1892, Stephen Crocker built five houses in the area, including a Queen Anne Victorian home, which still stands on the site.

Jacob Smith’s grave in Glenwood Cemetery. Courtesy of Ari Napolitano.

Fred Aldrich (1861–1957) moved into the Queen Anne house in 1894. A native of Van Buren County, Aldrich came to Flint when his father purchased the Flint Globe newspaper. Aldrich established the Otter Lake Enterprise newspaper in northeast Genesee County in 1880. He began working for his childhood friend William “Billy” C. Durant as a clerk at the Flint Road Cart Company in 1889. He became secretary of the Durant-Dort Carriage Company on its incorporation in 1896. As a banker, Aldrich was instrumental in building the Durant and Flint Tavern Hotels.

Some of Flint’s most haunting tales have connections to the locations and people tied to those pieces of land from the treaty, including a house located in Section Five of what is known as the old Smith Reservation. The Travel Channel’s The Dead Files investigated the location in an episode that aired in June 2013 titled “Battlefield.” The home was filled with spirits and possibly a demon. The Dead Files team performed an exorcism on the mother living in the home.

Another haunting tie is the Stockton Center at Spring Grove, considered to be Flint’s most haunted location. The house was built by Colonel Thomas Stockton and his wife, Maria, who was the youngest daughter of Jacob Smith. Learn more about Stockton in chapter 6.

AFTER JACOB SMITH

Flint continued to grow and prosper after Smith’s death. In 1835, the Village of Flint began with just over fifty-four acres. In 1855, the small but prosperous village officially became a city with around two hundred residents.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Flint was the center of Michigan’s lumber industry. It had reached its peak as a lumbering town in 1870 with eighteen lumber dealers, eleven sawmills, nine planing mills, a box-making factory and a dealer in pine lands. As the lumber industry boomed, the next industry emerged: transportation. Carts, wagons and carriages were needed for transporting lumber, as well as lumber workers and their families.

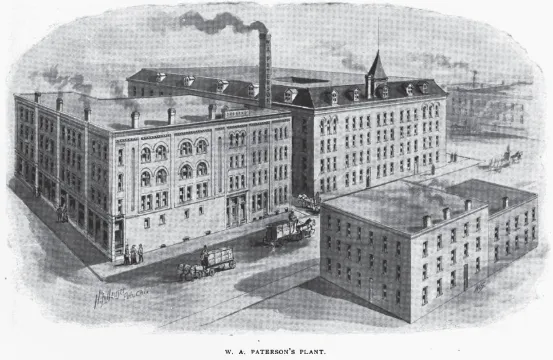

In 1869, the first major carriage factory opened. Incorporated in 1896, the W.A. Paterson Company grew into a three-building complex along Saginaw and Harrison Streets.

In the early 1880s, as the lumber industry faded, Flint Wagon Works was founded. James H. Whiting, manager of the Begole Fox lumber business, suggested the company make wagons. He partnered with Josiah W. Begole, David S. Fox, George L. Walker and Allen Beach Sr. and set up shop on Flint’s West Kearsley Street in a vacant Begole Fox lumberyard.

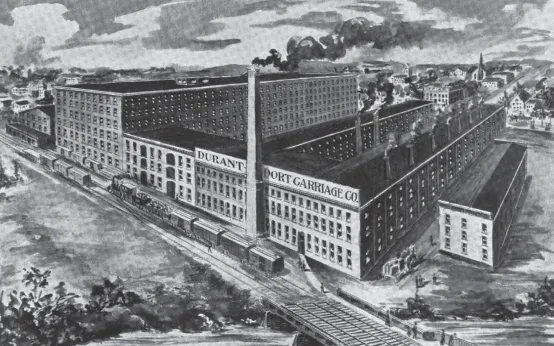

Josiah Dallas Dort and Billy Durant bought the Coldwater Cart Company in 1886 and moved it to Flint, renaming it the Flint Road Cart Company. In 1895, it was renamed the Durant-Dort Carriage Company. These three carriage companies became the original “Big Three.”

A drawing of the Paterson Factory. From the book Headlight Flashes along the Grand Trunk Railway System; Flint, Michigan.

In 1899, seven wrought-iron arches were erected to illuminate the Downtown Flint business district. The electric arches replaced gas lanterns. Flint, ever the source of innovation at the time, was one of the first cities to light up its streets in such a manner. Built by Genesee Iron Works, each arch held no fewer than fifty light bulbs. During holidays and parades, the arches were adorned with festive decorations.

Business was booming, and men from all over the United States came to Flint for manufacturing jobs. By 1900, Flint was producing more than 100,000 horse-drawn vehicles per year. In the early twentieth century, Flint became a successful automobile manufacturing city.

Judge Charles Wisner, a genius who patented five inventions and whose workshop still stands in the historic Crossroads Village, drove Flint’s first horseless carriage down Saginaw Street in the Labor Day Parade in 1900. The carriage moved like magic, wowing approximately ten thousand spectators before it eventually stuttered and stalled. But that ride lasted long enough to catch the eye of Billy Durant. Durant did not buy Wisner’s patent for the automobile, but the idea of a horseless carriage stuck in his head.

A drawing of the Durant-Dort Carriage Company. From the book Headlight Flashes along the Grand Trunk Railway System; Flint, Michigan.

In 1901, the Durant-Dort Carriage Company was the second business to plug into electricity, right behind the Flint Daily Globe newspaper. This completely changed the manufacturing industry.

Flint Wagon Works, a rival of Durant and Dort, pushed the city fully into the automobile craze in late 1903. President James H. Whiting made the decision to purchase David Buick’s fledgling Buick Motor Company to build engines for farm equipment. David Dunbar Buick and his chief engineer, Walter Marr, stayed with the company and convinced Whiting to manufacture the first Buick motorcar. In 1904, Flint Wagon Works had begun producing automobiles, but it was slow and costly. Whiting was frustrated. He dissolved the old Buick Motor Company and incorporated a completely new entity, the Buick Motor Company. Billy Durant then took over management of Buick.

In June 1905, Flint celebrated its fiftieth birthday with a golden jubilee celebration...