![]()

SECTION 1

THE GRAND CHALLENGE

HÅKAN NORDKVIST, who manages sustainability innovation at the IKEA Group, told a fascinating story recently. He was taking part in a panel discussion on the stage of the Grand Hotel’s elegant Winter Garden in Stockholm. In the audience were 150 business leaders, policymakers, and experts eager to hear the latest thinking about sustainability and business.

As Nordkvist explained, IKEA is now deeply involved in transitioning its energy supply to renewable sources. The company owns about 140 windmills and has installed more than 550,000 solar panels on its buildings around the world. By 2020, IKEA plans to produce more energy than it consumes, contributing to global sustainability while making IKEA more competitive.

What caught my ear was Nordkvist’s comments about a discussion in IKEA’s boardroom. When asked about the idea of investing in renewable energy, the company’s financial people apparently had urged against it, maintaining there was no economic case to do so. Investing in solar and wind would be more expensive than the alternatives, they’d pointed out. But when Ingvar Kamprad, the founder of IKEA, spoke up, he insisted that they should go ahead anyway. When asked why, Kamprad’s answer was simple: “Because it is the right thing to do.”

The story resonated with me because it reflects a huge shift taking place in the way that businesses treat sustainability. A decade ago, many companies dismissed sustainability as an aside—an engagement in corporate social responsibility (CSR) outside of core business. But today, companies are integrating sustainability into core business strategy. Issues related to climate change or ecosystems are no longer the exclusive realm of directors for the environment; they’re an agenda item for boardrooms. Resource efficiency, circular business models, low-carbon value chains, and environmental accounting are all key pieces of strategies, not only to be profitable but also to produce long-lasting companies.

Some game-changers are happening already. The B Team, a non-profit initiative started by Jochen Zeitz of Puma and Richard Branson of Virgin, has been promoting serious integration of sustainability across business sectors. Unilever, Royal DSM, and Walmart are each pioneering sustainable value chains in the food industry. Carl-Henrik Svanberg, chairman of BP, has lent his support to a global price on carbon, saying it’s not reasonable that oil companies should be able to pollute the atmosphere for free. General Electric (GE) has saved 300 million US dollars (USD) from energy and water improvements in their own operations (since 2005) and has generated more than 160 billion USD in revenue from technology solutions that have saved money and reduced environmental impacts.

More and more businesses have reached the conclusion that sustainability gives them an edge over competitors who can’t keep up with change. The old strategy of exploiting Earth’s natural resources and polluting the planet as much as possible no longer works, as The Economist noted not long ago in a special issue about the future of oil. Industries that continue to invest in fossil fuels are doomed to fail, the magazine maintained, not on environmental grounds primarily, but because clean energy will become so abundant, cheap, and attractive it will outcompete the volatile, dangerous, unhealthy, risky, and increasingly scarce fossil alternatives.

The writing’s on the wall. As the chapters in this section detail, humanity’s very survival depends on a deep shift in the way we think about natural resources, energy use, pollution, fairness, and sustainability. As pressures mount from population growth, climate change, ecosystem degradation, and the increasing likelihood of sudden changes in Earth’s behavior, a growing number of business leaders have discovered that a safe pathway into the future can also be a profitable one.

Walking down the snow-covered streets of Davos, Switzerland, during the annual World Economic Forum these days, one can’t help but notice that every company wants to brag about its most innovative ideas. Whether it’s the electric car manufacturer Tesla, VW E-Up, or Audi’s E-tron, solar technologies, or new lightweight carbon materials, everybody’s talking about innovation aimed at sustainability. Think about it: When a business really wants to show off today, it doesn’t hang its logo on the equivalent of a gas-guzzling Hummer; it proudly puts forward its leanest, cleanest, and coolest new product.

Because it’s the right thing to do.

The loss of rainforest such as this in the Bandan River area of Sarawak, Malaysia, may affect moisture feedback from the forest, thereby changing regional rainfall patterns.

![]()

1

OUR NEW PREDICAMENT

THE WORLD AS WE KNOW IT is a relatively new phenomenon. For most of Earth’s 4.5 billion-year history, conditions on the planet have been far less hospitable than they are today. It has only been during the past 10,000 years, in fact, that factors necessary for human societies to develop have been reliably present. Before that, Earth was often a horror show.

When our ancestors, the earliest hominids, first appeared in Africa some 2.5 million years ago, for example, they faced a series of crises as Earth shifted back and forth between punishing ice ages and lush warm periods. Even when modern human beings began to walk the planet about 160,000 years ago, survival was still not a sure thing. The world’s climate kept alternating between cold episodes of expanding ice sheets, water scarcity, low sea levels, and food shortages, and warm episodes of abundant water, high seas, and lush biomass resources. Although these swings weren’t extraordinary from a geological perspective—global temperatures varied less than 5°C (9°F) one way or the other—their consequences were huge for human survival.

Back then, the relatively small human population, fluctuating between a few million and tens of millions, lived as hunters and gatherers. During periods of extreme climate shifts, when it was hard to find food and shelter, they were confined to pockets of productive savannahs in Africa. In a critical cold period about 75,000 years ago, as DNA analyses have revealed, the entire human population may have dwindled to as few as 15,000 fertile adults, confined to the high plateau in northern Ethiopia. This constituted a profound crisis for our species. We’ve never been as close—in fact, one cannot be closer—to extinction. To find new sources of food, groups of survivors set out along the coasts of the Red Sea, which at the time may have been as much as 100 m (328 ft) lower than it is today (because so much freshwater was tied up in the polar ice sheets). Walking first through the southern Arabian Peninsula—then, as now, an arid and inhospitable environment—and then moving along the coast toward India, these groups, among others, eventually spread to Australasia and Europe some 40,000 years later.

It was the scale and rapidity of climatic changes that locked humanity into a semi-nomadic lifestyle. Sometimes these changes were abrupt. As researchers have discovered from ice cores drilled deep into ice sheets on Greenland, some changes over the past 100,000 years took place in a matter of only decades. About 11,500 years ago, for example, temperatures in Greenland shot up by 5–10°C (9–18°F) over a period of barely 40 years.

But then, about 11,700 years ago, Earth’s stormy climate tapered off, as we left the last ice age and entered a planetary state of natural harmony, the inter-glacial period we now call the Holocene. Humanity literally came in from the cold into a remarkably stable warm environment. Compared to what we faced during the Pleistocene 2.6 million years ago, humans now enjoyed relatively minor changes in climate. In fact, in both the Northern and Southern hemispheres, we quickly grew accustomed to an incredibly narrow range of climatic variation, with temperatures wobbling only about 1°C (1.8°F) up or down.

The impact was immediate. Almost as soon as we entered the Holocene, groups of hunters and gatherers in at least four different parts of the world independently invented agriculture more or less simultaneously. Clearly, the warm, wet, and predictable environment agreed with us. Within 1,000–2,000 years of this new regime, we saw a transformation of our way of life in many places from semi-nomadic hunting and gathering to sedentary farming, which proved to be the key to the development of modern societies. Agriculture allowed specialization, technology development, rules and norms, and dramatic growth in our capacity to provide food for populations.

It was at this point in history that we saw the rise of the earliest advanced human cultures: the Longshan Neolithic agrarian cultures of the Yellow River Valley in China; the ancient Egyptian irrigation societies along the Nile; the Mesopotamian irrigation societies along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers; the Greek and Roman empires; the Islamic civilizations in a large part of Africa and Central Asia; the agrarian societies of the Maya civilization in Central America. In their own ways, each of these agrarian cultures developed into advanced societies. Civilizations evolved through the Middle Ages, the evolution of the feudal merchant societies, eventually coupling with the rise of modern science during the late Renaissance, and ultimately the birth of nation states. We reached our first billion people by the year 1800, growing to three billion by the middle of the 20th century.

The onset of the Holocene, in short, was the planetary equivalent of establishing the ultimate shopping mall for humanity. Suddenly we had a reliable source of goods and services delivered from a stable equilibrium of forests, savannahs, coral reefs, grasslands, fish, mammals, bacteria, air quality, ice cover, temperatures, freshwater availability, and productive soils. The point of this story is as simple as it is dramatic: We still depend on the Holocene for our prosperity and wellbeing. It is the Garden of Eden for our civilizations. In fact it’s the only state of the planet we know that can support modern societies and a world population of more than seven billion people.

That’s why what we’re doing right now ranks as the most disturbing event in the history of humankind: We’re pushing our planet out of the Holocene into new and uncharted territory.

WELCOME TO THE ANTHROPOCENE

It didn’t take long—only a half-century or so—for the rapid pace of industry and agriculture to threaten the world as we know it. Since the great acceleration of the human enterprise, kicking off in the mid-1950s, humanity’s wide-ranging impacts—including climate change, chemical pollution, air pollution, land and water degradation, nutrient overload, and the massive loss of species and habitats—have put nearly all of Earth’s major ecosystems under stress. In fact, we humans, Anthropos in ancient Greek, have become such a massive source of global change that we now constitute a geological-size force on the planet, one even more extensive in magnitude and pace than volcanic eruptions, plate tectonics, or erosion. With reckless abandon, we’ve introduced our own geological epoch, the “Anthropocene.”

The trend started in the mid-18th century with the industrial revolution, when we learned how to exploit fossil fuels as a new, cheap, and effective energy source. This broke many constraints that had previously hampered social and economic development. Now we could clear land in an unprecedented way, changing a landscape almost instantly. We developed an industrial process, only possible with fossil-fuel energy systems, to convert nitrogen from the atmosphere into fertilizers, breaking a fundamental constraint on food production. We improved sanitation systems, which, along with major medical advances, yielded great benefits for human health and improved urban environments. Our populations grew rapidly as a result of higher life expectancy and wellbeing.

Manufacturing systems emerged that used fossil fuels to greatly increase production of goods. Unknown to us at the time, this rapid expansion of fossil-fuel usage was slowly raising CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere. By the early 20th century, CO2 concentrations had reached the highest limits since the Holocene epoch began. Even back then, in other words, we were saying goodbye to the world as we know it.

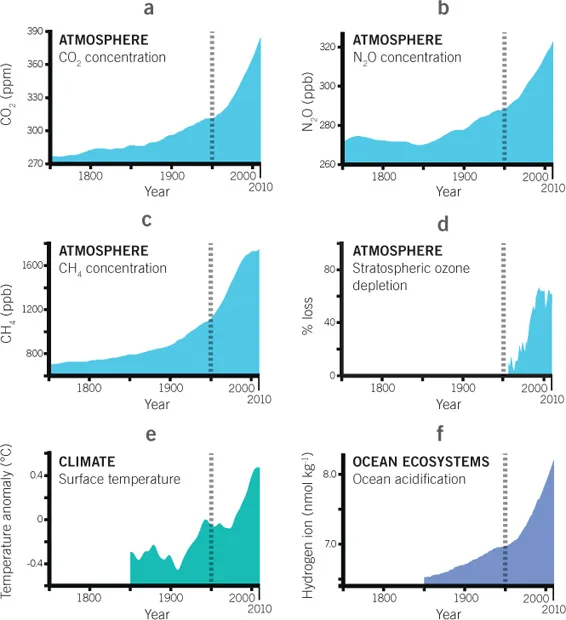

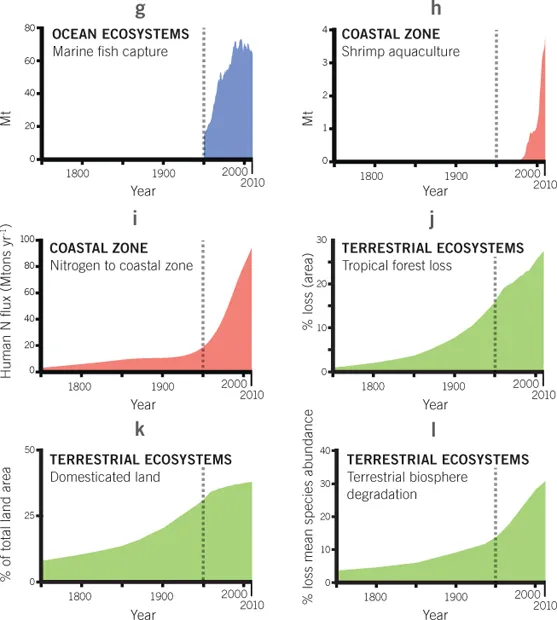

Figure 1.1 The Great Acceleration of Human Pressures on the Planet Starting in the mid-1950s, there has been a rapid increase in changes, on a global scale, to all the environmental processes that form the basis of our modern economy—all of it caused by human activity.

These curves reveal accelerations in the following: (a) the atmospheric concentration of CO2, (b) the atmospheric concentration of N2O due to agriculture and burning fossil fuels, (c) the atmospheric concentration of CH4 due to the expansion of livestock-production systems, (d) the percentage of ozone-layer loss due to ozone-depleting chemicals used by humans, (e) the anomalies in average temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere, (f) the increase in ocean acidification, (g) the percentage of global fisheries either fully exploited, overfished, or collapsed, (h) annual shrimp production as a proxy for coastal zone alteration, (i) nitrogen pollution of coastal areas, (j) the loss of tropical rainforest and woodland in tropical Africa, Latin America, and South and Southeast Asia, (k) land converted to pasture and cropland, and (l) the estimated rate of extinction of species on Earth. (The abbreviations used above are as follows: ppm/ppb is parts per million/ billion, nmol kg is nanomole per kilogram, and Mt is million tons.)

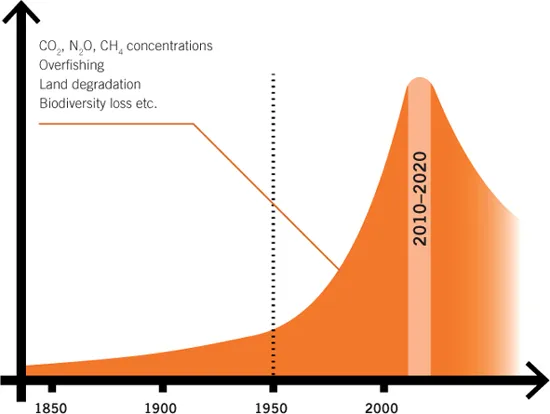

Figure 1.2 Exponential Impacts. The world embarked on the “Great Acceleration” of the human enterprise in the mid-1950s. At that time, the global population was about three billion people, with fewer than 0.4 billion having a lifestyle that significantly and negatively affected the global environment. At the same time industrial growth affected multiple environmental processes, leading to an exponential rise in negative pressures. Today we are at the top of that curve, maintaining the pressure on the planet. More and more science shows that we have reached a saturation point. We have hit the ceiling of what the planet can cope with, risking the onset of catastrophic changes. We urgently need to reverse the trend of detrimental global environmental change. This needs to happen in the current decade for most environmental processes in order to provide stable “Holocene-like” conditions in which we can secure prosperity in a still-growing world.

It wasn’t until the mid-1950s, though, a period we now refer to as the “Great Acceleration,” that the impacts of humankind’s activities grew to dangerous levels. There were still relatively few people on the planet at that point—about three billion in 1955—and we were still working under the mistaken assumption that environmental issues were separate from social and economic ones. But soon, by almost every measure, our growing populations and unsustainable habits piled on more and more environmental pressures. No matter which parameter you chose to look at—whether CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere from fossil fuels; nitrogen concentrations in the soil from agriculture and industry; methane concentrations in the air from livestock; ozone depletion over Antarctica; rising surface temperatures; floods and other extreme weather disasters; disappearing fish stocks; coastal disruption from fish farms; nitrogen pollution of coastal waters; loss of tropical rainforests; wild habitat converted to croplands; or increased rates of biodiversity loss—the trend was the same, with a sharply rising curve head...