eBook - ePub

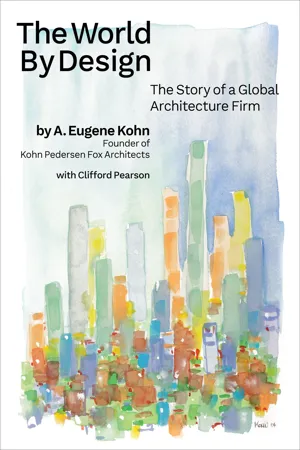

The World by Design

The Story of a Global Architecture Firm

- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Sharing stories and inspiring lessons on leadership and design, one architect explains how he helped build one of the world's most successful firms

Founded on July 4, 1976, Kohn Pedersen Fox quickly became a darling of the press with groundbreaking buildings such as the headquarters for the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) in New York, 333 Wacker Drive in Chicago, the Procter & Gamble headquarters in Cincinnati, and the World Bank Headquarters in Washington, DC.

By the early 1990s, when most firms in the U.S. were struggling to survive a major recession, KPF was busy with significant buildings in London, Germany, Canada, Japan, Korea, and Indonesia—pioneering a model of global practice that has influenced architecture, design, and creative-services firms ever since. Like any other business, though, KPF has stumbled along the way and wrestled with crises. But through it all, it has remained innovative in an ever-changing field that often favors the newest star on the horizon.

Now in its fifth decade, the firm has shaped skylines and cities around the world with iconic buildings such as the World Financial Center in Shanghai, the International Commerce Centre in Hong Kong, the DZ Bank Tower in Frankfurt, the Heron Tower in London, and Hudson Yards in New York.

Forthright and engaging, Kohn examines both award-winning achievements and missteps in his 50-year career in architecture. In the process, he shows how his firm, KPF, has helped change the buildings and cities where we live, work, learn, and play.

"A must-read for all of those who love cities and the buildings and skylines that define them." —Stephen M. Ross, chairman and founder of The Related Companies

Founded on July 4, 1976, Kohn Pedersen Fox quickly became a darling of the press with groundbreaking buildings such as the headquarters for the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) in New York, 333 Wacker Drive in Chicago, the Procter & Gamble headquarters in Cincinnati, and the World Bank Headquarters in Washington, DC.

By the early 1990s, when most firms in the U.S. were struggling to survive a major recession, KPF was busy with significant buildings in London, Germany, Canada, Japan, Korea, and Indonesia—pioneering a model of global practice that has influenced architecture, design, and creative-services firms ever since. Like any other business, though, KPF has stumbled along the way and wrestled with crises. But through it all, it has remained innovative in an ever-changing field that often favors the newest star on the horizon.

Now in its fifth decade, the firm has shaped skylines and cities around the world with iconic buildings such as the World Financial Center in Shanghai, the International Commerce Centre in Hong Kong, the DZ Bank Tower in Frankfurt, the Heron Tower in London, and Hudson Yards in New York.

Forthright and engaging, Kohn examines both award-winning achievements and missteps in his 50-year career in architecture. In the process, he shows how his firm, KPF, has helped change the buildings and cities where we live, work, learn, and play.

"A must-read for all of those who love cities and the buildings and skylines that define them." —Stephen M. Ross, chairman and founder of The Related Companies

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The World by Design by A. Eugene Kohn,Clifford Pearson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Perspective

For more than four decades, Kohn Pedersen Fox has shaped skylines and redefined cities around the globe. Launched by William Pedersen, Sheldon Fox, and me on July 4, 1976—at the nadir of a long recession—it has taken a few hits over the years but has prospered in both good times and bad. Along the way, it has had the good fortune to work with some remarkable clients, engineers, and consultants in creating buildings and places that have contributed to an urban resurgence transforming cities as varied as New York, Shanghai, London, Hong Kong, Frankfurt, and Jakarta. Just as important as any individual project has been the creation of a firm that embodies a set of values defined by its founders. My goal as an architect has always been to create a built environment that improves the lives of people and brings them joy, regardless of their ethnicity, nationality, religion, or economic status. KPF embodies that goal in action.

When Bill, Shelley, and I started KPF, we shared a vision of an architecture firm working as a team and pursuing excellence together. We weren’t a single-name firm banking on the talent and allure of one big-time player. Nor were we a collective of design studios, each with its own star at the top. The three of us liked sports a lot and thought of KPF as a team with members playing different positions but all working toward a common goal. When I was a kid, I wanted to be a baseball player and later toyed with the fantasy of becoming a sports broadcaster. I lacked the extraordinary talent needed to be a professional athlete, but I learned how to play on a team. Bill was a superb athlete and played hockey at the University of Minnesota with an eye on the National Hockey League. Corny as it might be, sports were a recurring metaphor for KPF. Fielding a strong team in the New York City corporate softball league was always important to us, and for many years Bill and I went to bat, literally, for the firm. I admit we sometimes hired people for their baseball skills—which helped us win five league championships—but they had to be good at architecture, too. Playing together was essential to us.

From the beginning of KPF, I understood that running an architecture firm was perhaps the most difficult kind of leadership task. Shelley and I had served in the military as officers during the Korean War—he in the Army, I in the Navy—so we knew about chains of command. The military is set up for leadership. Rank has its privileges and is identified very quickly, by stars and stripes. You have to listen and do what you’re told. While officers usually have college degrees, most of the people they command do not. Corporations are different, but they too have management structures that are pretty well spelled out. From the CEO through the department heads and down to the rank and file, everyone knows his or her position within the company’s lines of responsibility. On sports teams, you have owners, coaches, scouts, and players—all with specific roles. They don’t win unless they work together. That’s the key. You can have a fantastic quarterback, but he needs a great offensive line to protect him and receivers to catch the ball. One player’s greatness is dependent on others.

But architecture firms—indeed, all creative service enterprises—are different. Architects are trained to be individuals, to shine as solo talents. Most are college educated, and today more and more of them have master’s degrees, too. So you get a lot of big egos and lots of ambition. They’re smart and have strong ideas. They’re all critics and will take apart everyone else’s ideas. They all want to be the next big star. That makes it hard for them to check their need for individual recognition. Leading a group of people like this, especially a large one, is really difficult. You can’t run an architecture firm like a military unit or a corporation or even a sports team. It won’t work. You’ll lose your best people pretty quickly or won’t be able to attract them in the first place.

Shelley Fox, Bill Pedersen, and I enjoy a light moment in our offices on West 57th Street with a model of a tower we designed for mid-town Manhattan that didn’t get built.

Jamie von Klemperer (right) is now president of KPF, leading a new generation of principals that includes Josh Chaiken (left).

At an event honoring Philip Johnson, I joined a group of illustrious architects all wearing copies of his famous eyewear. I’m the one on the right with my head even with the Chippendale-inspired top of Johnson’s AT&T Building.

Architecture schools, films, and books peddle images of the heroic architect—the master builder, the genius who does everything alone. It’s sexy and it sells. But it’s a myth. Architecture is actually an incredibly collaborative effort. Bill, Shelley, and I knew that from day one. All of us were trained as architects and read The Fountainhead, but none of us wanted to play the hero. It helped that we had different personalities and complementary skills. I’m a very good designer, but Bill is one of the best in the world, so I let him take the lead in that area. Shelley was the most organized person I’ve ever met. At the University of Pennsylvania, where he and I went to architecture school together, Shelley was the only student who would have his project done the day before a design charette ended. He would show up for the final review well rested and dressed in a beautiful sports jacket and tie while everyone one else would look like hell—unshaven and sleep deprived. He was never late. Never. So at KPF, Shelley took care of managing operations. I was the most outgoing of the three and the biggest risk taker. As a result, I took on the role of president and leader, which in the beginning meant getting the work—finding new opportunities and convincing clients to give us jobs. None of us tried to do everything. We each needed the other two. But we could back each other up, if needed. It was a formula that succeeded from the beginning and kept working for many years.

Most architecture firms don’t last very long after the founders retire or die. Usually they sell to or merge with another firm, or their new leaders change the firm’s name and identity. We wanted Kohn Pedersen Fox to be different. From the start, we talked about training the next generation of leaders, developing people who could take over from us. We weren’t a single-name brand or a bunch of star individuals, so this seemed like the right way to go. We liked the idea of creating something bigger than the three of us that would live longer than any of us. To do that we needed to hire people who were as good as or better than the founders.

At the time of this writing, KPF has completed more than three hundred projects (many with multiple buildings) in forty-one countries and won nine National Honor Awards from the American Institute of Architects. We were the youngest practice to be recognized with the AIA Architecture Firm Award (in 1990) and have touched the lives of millions of people. In the process, we have played a critical role in the biggest global construction boom in human history, which has reaffirmed the central role of cities in developed and developing countries alike. At the founding of KPF in 1976, though, the US was still reeling from the oil embargo of three years earlier, and New York City was struggling with its near default the year before. Big corporations were fleeing cities, and crime was on the rise. A lot of things seemed broken. But I just knew KPF would succeed. I’m not sure why I was so confident, but my gut told me to press forward, and I’ve learned to trust my instincts. Certainly, I was—and remain—an optimist.

From the beginning, Bill, Shelley, and I wanted to design commercial projects—such as office towers, apartment buildings, hotels, and retail complexes—because they have the most impact on the public life of cities. Many high-profile architects in the 1970s turned up their noses at such projects, seeing them as mostly dumb boxes with repetitive programs and lots of bottom-line pressure. Instead, they focused on houses, museums, and cultural facilities. But commercial projects are the dominant building type in cities and we felt it was wrong to ignore them. We wanted to tackle the challenge and make these buildings work as positive contributors to a city’s fabric and a neighborhood’s character. If we could do that, we could make a significant contribution to the architectural profession and urbanism.

In our first year, we landed a few significant projects and established relationships with clients who ended up becoming repeat customers and lifelong friends. Within our first few years, we had become a darling of the press and had a major profile in the New York Times Magazine to our credit. We worked really, really hard and had a lot of fun doing it. There were bumps along the way, of course, but we rode a remarkably steady path to the top. I think a lot of this success was due to the fact that Bill, Shelley, and I remained good friends. We liked each other’s families and would vacation together. Through all the years, we always respected one another and enjoyed working together. On numerous occasions, clients would look at the three of us and shake their heads in surprise. “You guys seem to actually like each other!”

In 1989, KPF took its first steps abroad, landing jobs in London and then Frankfurt. By the end of the 1990s, we were a truly global firm with projects in Japan, China, Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore, Indonesia, the United Kingdom, Holland, the Czech Republic, Germany, France, the UAE, and many other countries. It was exhilarating to engage with clients, government officials, design consultants, and the public in foreign places and learn about their cultures. When you design a large building in a city, you need to research everything about that place—its climate, its geology, its building traditions, its economy, and its society. As an outsider, you must prove you have done your homework and really studied the local conditions and the larger context. It’s a huge challenge, but it makes you smarter.

Stephen Ross, the head of the Related Companies, came to one of my Harvard Business School classes and talked to my students about his approach to real estate development.

My wife Barbara (second from right) is active with many nonprofit organizations, including the Paul Taylor Dance Company. Here we are at a Paul Taylor gala with actors Kevin Kline and Phoebe Cates.

Right after the attacks on September 11, 2001, many people wondered if anyone would want to work or live in tall buildings anymore and if people would start abandoning big cities for places that might be seen as safer. Remarkably, the opposite happened. The determination of th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Chapter 1: Perspective

- Chapter 2: Beginnings

- Chapter 3: Launching a Firm

- Chapter 4: Dancing with History

- Chapter 5: First Steps Abroad

- Chapter 6: Pacific Overtures

- Chapter 7: Millennium Approaches

- Chapter 8: London Fire

- Chapter 9: Vertical Urbanism

- Chapter 10: Greater than Ever

- Chapter 11: The Two Bills

- Chapter 12: Re-Generation

- Chapter 13: Future Perfect

- Acknowledgments

- KPF Principals and Employees

- KPF Key Projects, 1977–2024

- Index