![]()

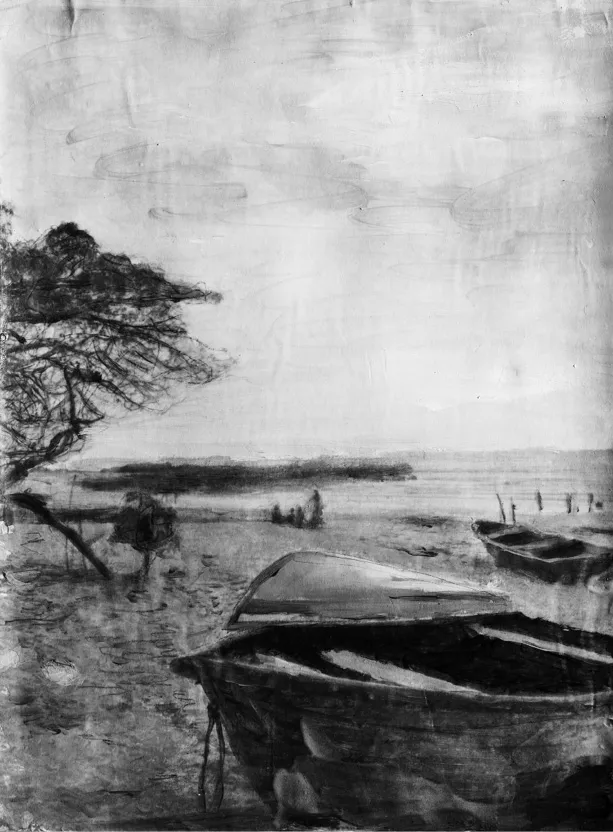

We were seated at a weathered picnic table on the beach behind the Fragata Lounge with a view of old fishing boats tossing on their moorings in the wide bay. The high tide was practically touching our feet. Rachel was across from me talking in Spanish with her aunt, a few cousins, and some others. She had wanted me to meet her family.

Rachel’s aunt María José was wearing a tight, low cut dress that left little to the imagination. While María José spoke, Rachel translated in a musical voice trained over the years to rise and fall in counterpoint with the surf. “The women in Fragata are the most beautiful in the world,” said María José. She paused to let this sink in. “We’re known for this.” I guessed she was in her middle fifties, about ten years younger than me.

“Big breasts and butts,” she continued. María José was dressed to be noticed and when I took a look, she smiled. Rachel’s aunt had the carriage and confidence of a lady who has been beautiful her entire life. “Men hear about this place and they arrive in luxury convertibles. They have money and after a few days the girls drive off in the fancy cars with hardly a wave. I left when I was seventeen. All the beautiful ones leave.”

I looked over at Rachel who had never left, who would like to leave, if someone would take her. Unless that time had already passed for her.

“Really?” I asked while Rachel translated. “Where do they go?”

“They go all over the world,” she said, “Spain, New York.”

I tried to take this in. Men came to this tiny Costa Rican village of 150 and few more to take away the beautiful women.

“I went to Italy with an older man.”

“The most beautiful women in the world?”

“Yes,” she said smiling at me. “But when they reach the age of thirty-five or forty, they return here.”

The warm Pacific was washing onto my sandals, but the others didn’t seem to notice as they ate rice and beans with fried eggs.

Ten days earlier, I’d been driving from the airport along a hot, deeply rutted dirt road to nowhere, or so it seemed. On both sides of the road were rows of skinny teak trees covered by gray dust as if there had been a frost. Occasionally a doleful dark-skinned woman appeared walking slowly toward me from the gloom or a sorrowful cow or several emaciated horses. Every mile or two a little dog appeared to be wandering, confused or sleeping in the road. Then came a six-year-old on a bike pedaling furiously for his life. It was a beaten landscape, which mirrored my state of mind arriving here from New York. Eventually the teak trees gave way to dusty lush mango trees heavy with dangling gray fruit. Sooty air made it challenging to stay on the road as I passed slatted wooden shacks snowed in by road dust with men in undershirts, sitting in chairs, drinking beer, the wash getting filthy on the line. A tiny grocery with its sign obliterated. How did these people breathe?

Until the curtain lifted unexpectedly, gloriously, to the Pacific on the south side of the road, a white beach, trussed on both sides by rocky cliffs, a calm blue-green ocean with a few moored skiffs somewhat protected by a breaking reef fifty yards offshore. A perfect place to cast a line. I stopped for lunch at the tiny fishing village, rickety homes on the beach, several pangas pulled up on the sand beneath palm trees, one huge Guanacaste tree in the center.

Rachel translated as her aunt spoke of the young women taken from Fragata like precious minerals. Meanwhile the others at the table are speaking rapidly in Spanish. I try to grab a word or two. I decide they are saying I will take Rachel away like all the others. But does she want that? Or do I?

Unlike her aunt and her younger sister, Sondra, Rachel never shows her breasts. Even in the heat of the afternoon she dresses modestly in shorts and a loose long-sleeved shirt. At thirty-six Rachel is already too old. It’s almost time to come back to the tiny village she never left. She feels the sadness of this, and I could love her for it.

A few chickens wander through the sandy yard. Rachel’s wash hangs haphazardly across a neighbor’s picket fence. Her eighteen-month-old baby, Angelo, is standing in his playpen screaming, let me out.

“How long has this bar been here?” I ask Rachel, who is distracted by her screaming child.

“Why don’t you ask my aunt?” she answers curtly. “She came here to speak to you.”

I supposed it was true. María José had walked down from a small house on the hill to meet Rachel’s new friend from New York. María José and I were a perfect match, an appropriate age difference and she loved good writing. Except the whole story for me was Rachel. I was straining to be polite to her aunt who was dressed for a party.

“How did this place get its start?” I asked.

“My sister, Rachel’s mom, bought the property for next to nothing, less than a hundred dollars. Actually, she had a big king-sized bed in her house, sold it and bought the land. She put up a little bar but after a year she lost interest. She wanted to live in San José. She was beautiful then. All the girls here know that their time will pass quickly. They are racing against time.”

I was watching Rachel’s face while her aunt spoke. When she is relaxed Rachel has a soft welcoming face, but when she is cornered or nervous her face puckers and creases, the coming attraction of old age.

“By luck an older man from the states came here and rented the lounge. That was before we had it fixed up,” Marí a José said, a quick trace of smile underscoring her irony. “I met him the year before I left for Italy. We’d talk sometimes on the beach where he liked to sit in the morning to smoke a cigarette. He always carried a book and hummed classical music. He told me about Gabriel García Márquez. He said that this village was right out of a Márquez novel.”

As she spoke the tide washed over my ankles. I noticed an old man tossing a handline from a rock a hundred yards down the beach. I wondered what he was fishing for.

“He was a kind man, cultured and gentle. He didn’t care for people his own age. He liked children. Each afternoon he invited all the town kids inside the lounge and closed the gate,” she continued. “He gave the kids burgers and fries and ice cream. Then he put cartoons on the little TV, and after that, videos with kids touching one another. He was very inventive. He taught the children to play sex games with one another and then he played along with them. These activities went on for several years until he was arrested. One of the little boys from that time, Daniel, still comes here for a beer in the evening. I can introduce you if you like.”

I nodded yes, but my mind was all over the place. Rachel moved off to the kitchen to prepare the lunch. One of the fishing boats had caught my attention. It was heeled onto its side very close to the building surf. One large wave and the boat would be swamped. María José was looking at me directly, waiting, perhaps for another question. I just wasn’t so interested in the history of this run-down place with broken benches and a few torn beach umbrellas.

I smiled to be polite.

“He might tell you more about those days,” she said, surprising me with her fluent English. “But he is very moody. Some evenings he is pleasant but other times he sits for hours and won’t say a word.”

Before leaving, Marí a José told me that she had a home nearby. She pointed to a hill in the distance as an invitation. She had a beautiful smile. From the kitchen, I could smell the shrimps simmering in garlic.

I didn’t know what to say to María José. I didn’t want to hurt her feelings.

•

It was April, high point of tourist season in Costa Rica. Hotels and restaurants and even broken bars like this one had to make a few colones before torrential rains came in August, and Americans stopped flying into Liberia and San José to party and explore remote beaches. When the rains came the tiny bridges and dirt roads leading to Rachel’s village would be flooded out, and the locals would hibernate in damp shabby homes, watch soccer on TV.

Each morning I met Rachel and we sat on torn beach chairs beneath a palm, talking until it was time for her to begin preparing shrimps, red snapper, or chicken on the wood stove, unless Sondra was in a good mood and happened to come in to do the cooking.

“When the pedophile left, the lounge went to shit,” Rachel said returning to the story of her life. I had the feeling Rachel had told this story before and would need to tell it again and again. “The way he had it fixed up for the kids was charming, painted in gay colors, animal drawings on the wall. I was studying for one year in San José. I wanted to be a doctor. I’d had this dream from when I was a child. When I came back to visit after he was arrested, drunks and addicts had moved into the lounge. Everything in the place was broken, the stove and refridge were gone. They’d shit and pissed on the floors. The pedophile had made it beautiful. They turned it to sin.”

So much of Rachel’s passion and remorse went into her story. Occasionally I took her hand while she spoke. It felt like we were together in this beautiful ocean world, joined. But after ten or fifteen minutes, she gently took her hand back.

“It’s sweating,” she said a little sadly as though it were a malady. She turned over her palm to show me little rivulets of moisture on her palm.

Okay, too hot for holding hands. But just sitting close to her was intoxicating.

“So you came back to the lounge?”

“Sí … no one else could do it. No more school. I needed to make money for my family. My mom was away with a sea captain boyfriend. Sondra had another life. She’s always had another life…. I was here. I’m always here. I gave massages to tourists for a year in Nicoya and saved enough to buy a stove and a pizza oven.”

Soon we were joined by María José, who often took morning walks on the beach. The two women talked rapidly in Spanish as if I weren’t there. I could hardly catch a word. They would have talked for an hour but I interrupted.

“I was curious about why you said this village is right out of Márquez?”

“Just look around,” María José said with her delightful smile. “The beach life is very sexual. Everyone’s almost naked.”

María José was almost naked in a skimpy bikini. Not Rachel, who was again wearing a long-sleeved white shirt.

“In the North you are super cold and you don’t show more than your eyes. The women here are very beautiful, even when they return to the village. A lot of shape. The men are lean and strong from physical work. You’re drinking rum at night sitting by the ocean. You’re eating seafood. Drink some more. You’re almost naked. You’re talking with someone, touching a little. You walk down the beach together. It’s very natural…. Doesn’t matter so much who it is, a man or woman … or maybe he’s the lover of your sister…. It’s part of the life here.”

“Really?”

Rachel nodded, sí.

“I need to read Márquez again.”

“You don’t need to,” said Rachel’s aunt with her generous smile. “It’s all right here.”

•

I was thirty years old when I sold my first novel to a renowned editor at Random House, Joe Fox, who had worked on the celebrated fiction of Ralph Ellison, Phillip Roth, and Truman Capote. The day before I went to his office for the first time, Truman Capote’s obituary had appeared in the New York Times along with quotes from my new editor. On that first meeting, Joe remarked on my “narrative talent,” a term I didn’t quite understand, and then said to me with his trademark smirk, “I lost Capote yesterday but today I got you.” The irony didn’t escape me, but I knew the book was good and so did he.

I’d gone from zero straight to the top. Random House, Roth, Capote, and me. While working on revisions for half a year, Fox—that’s how he was known in publishing circles—and I became friends. We went drinking together, talked books, sports, and his broken heart after his much younger wife left him. Joe took me to swanky restaurants frequented by literary heavyweights, one night joining George Plimpton and Gay Talese for drinks at Elio’s. For sure I was a rookie but we were all on the same team, or so it seemed. I’d made it into the big leagues.

My novel was reviewed warmly by the New York Times. My wife showed the review to her girl friends and parents living in Ohio, but in truth, my writer’s life and vainglorious aspirations were boring to her. It was a good review but without the superlatives I’d hoped for. In my mind I typed them into the review and over time I came to believe they’d actually been there.

My wife was an Ohio girl who had quickly decided that New York was unfriendly and without redeeming charm. This confused me because New York made me feel alive. Many nights I narrated stories I encountered on the subway or on the street chatting with strangers that occasionally became my characters. I tried hard to win her over, but my fervent shop talk was boring to her. Often when I spoke of my writing, Beth waited a respectful moment or two before flipping on the TV.

Our first months together had been a sexual hurricane, and any differences between us were lost in passion. But over the expanse of seven years, and almost without noticing, we’d become strangers at home. When she finally left me to move back in with her parents, it didn’t feel like a catastrophe. In truth, heartache was wonderful to feel again and I coveted what little I had. I could draw on it and put this mistaken marriage into a book.

And I was writing again. That’s what I loved, spending days making stories, refining sentences and paragraphs. I wanted to fill a bookshelf with my novels like Roth and Updike. I was certain that I would. Joe was still my friend. The Times had referred to me as a “promising young author” and I tried to hold onto that as the years passed.

My second book took me more than five years to complete. Joe wouldn’t buy this one, which hurt a lot. His note to me was gentle but brief and I was too insecure to ask for a long explanation. After a dozen rejections my agent sold the book to Putnam. The Times didn’t review my second novel and those few reviews that appeared in obscure places were south of lukewarm. I tried to rewrite them in my mind so that I could sleep nights.

•

“Maybe...