![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE MAKING OF A KENTUCKY GENTLEMAN

Cut the Crap Principle 1: There’s no excuse for failure because we can always do things better.

While my parents, grandfather, aunts, and uncles usually voted for Democrats, they were staunch conservatives in their approach to life. My parents were intolerant of excuses for poor performance or poor behavior. On many occasions, I witnessed them finding creative ways to solve their personal problems and challenges, and I have seen other people face the same problems and challenges and simply give up.

My parents taught me that most of life’s problems are within our control to resolve and that it is our personal responsibility to do so. My mother made me gentle, and my father made me a man.

My mother was a saint. She was the most beautiful woman in the world. She used to claim that she was a softy with a tender heart, especially for underdogs; however, she was clearly not a pushover. She was a combination of steel, resilience, and perseverance. She never gave up on herself, and she never gave up on me. She was a good listener, and she was nonjudgmental of others, no matter what they experienced in their lives. She was a natural caretaker, counselor, social worker, and therapist.

For years, my mother worked all day at Eastern State Hospital, a large psychiatric hospital in Lexington, Kentucky, only to return home in the evening to prepare dinner for her family and then accept pressing, late-night phone calls from other women and friends. These callers were fighting giants in their lives, including bipolar disorder, alcoholism, poverty, physical abuse, and depression.

My father always believed that every healthy, grown man needed to be responsible and accountable to himself and his family, not a burden on his community, country, friends, or family. His favorite saying was, “If you can’t find a good job, plant a tree. Do something to make a difference, but for God’s sake, get a job and don’t be lazy.” My father believed that “most people in this world are simply lazy and too ornery to change their ways.” He always thought that things could be done better. He was an early adopter and pioneer of the Cut the Crap and Close the Gap management approach. He was clearly a process-improvement trailblazer as early as 1950, ten years before I was even born. This is why I strongly embrace this management approach today.

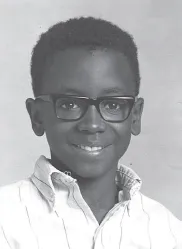

After receiving training on the Cut the Crap and Close the Gap approach from my father for the first twenty-nine years of my life, I became obsessed with process improvement and closing performance gaps in my personal and professional life. Even when I completed my chores on our family farm, like feeding the hogs, spreading manure over our fields, cleaning up the barn, parking the pickup truck and tractor in the barn for the night, or when I got an B in a difficult subject in school or perfectly played “At the Cross” on our family piano, my father would still say, “Is that the best you can do? There’s always room for improvement.” At the time, I thought my father was just being unfair to me, but today, though he’s been in heaven since 1989, I still respond to his guidance, and I even hear his voice saying there’s always room for improvement.

My father beat the odds all his life. He lost his mother, Mollie Coleman, who died at age fifty-two in 1933, when he was only ten years old. Right after her funeral, he had to be a little man. He became the caretaker for his youngest sister, Anna, and he had to care for his father, who was suffering from loneliness, depression caused by losing his wife, and alcoholism. My father deeply mourned the loss of his mother for next fifty-nine years of his life. He was overwhelmed by a sense of abandonment, saying often, “My mother died on me when I was ten years old.” While I never met my father’s mother, I somehow joined him in this mourning process. It impacted my own life and created in me a difficulty in accepting deep loss and abandonment, too. I even miss Mollie Coleman till this very day, and I’m still sad she died at such an early age.

In his early twenties, the United States Army drafted my father into service, and he was sent off to fight the Nazis in Italy during World War II. He faced a fierce enemy that sent massive fire, bullets, and bombs his way, but he survived. After his service, he returned to an American society that did not honor his service but rather mistreated him because of the color of his black skin. Through it all, my father remained focused and did not allow this injustice to blow out the candle in his life. Till the day he died, he stayed focused on seizing the moment that was available for him and his family in America.

My father, who was born during the Great Depression, believed that walking away from a problem was never acceptable. He’d lost his childhood the day he lost his mother, and as a result, he was a grown man for fifty-nine of his sixty-nine years. He had an intense disdain for anyone who was not willing to embrace responsibility. As a result of facing a challenging life at a very young age, he developed the divine gift of being a problem solver. He was obsessed about closure and bottom-line results, solving difficult problems, and protecting and providing for his family. Maybe this is why his young heart gave out at the early age of sixty-nine.

My father was an incredible multitasker—a farmer, a postal mail carrier, and a waiter at private parties that were hosted in the homes of prominent, multimillionaire Kentucky horse breeders. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in agriculture from Kentucky State University, but at the end of the day, the best job in Lexington, Kentucky, for an educated black man was being a mail carrier for the United States Postal Service.

Of all the jobs my father had, he enjoyed being a waiter at the big, private parties. That’s where he earned a special master’s degree in business administration from prominent Kentucky horse breeders and successful businessmen, like Mr. Leslie Combs, owner of the great Spendthrift Farm of Lexington.

According to New York Times journalist Thomas Rogers, “Spendthrift Farm, which Mr. Combs bought in 1936 with a $600,000 inheritance and proceeds from selling an insurance agency he had founded in West Virginia, enjoyed early prosperity and grew from 126 acres to 6,000.

“After World War II, Mr. Combs revitalized the practice of syndicating stallions, beginning with Beau Pere, whom he syndicated to 20 investors for $5,000 each. He later syndicated such champion thoroughbreds as Nashua, Majestic Prince and Raise a Native.”

Furthermore, Thomas wrote, “Spendthrift, named for a famous racehorse owned by Mr. Combs’s great-grandfather, was once the home of Seattle Slew and Affirmed, the Triple Crown winners of 1977 and 1978, and the farm may have reached its peak in stallion syndication in 1978, when those two champions were syndicated for $12 million and $16 million, respectively.”

According to my father’s many stories, Mr. Combs seemed to be very determined to achieve perfection, profit, and success in his horse breeding business. My father always told me stories about how he was teased by the other waiters during Mr. Combs’s private parties for being what they called “Spendthrift Farm’s Biggest Uncle Tom.”

Mr. Combs would often rely on my father’s advice in dealing with a given prospective buyer of his young thoroughbreds. My father would always tell the story about how Mr. Combs would almost come to tears after receiving a large, six-figure check from a wealthy international buyer of one of his thoroughbreds. Mr. Combs would turn to my father and ironically say, “Coleman, they stealing all of Cousin Les’s ponies today. Cousin Les is barely making a dime.”

At one of Spendthrift’s big parties, Mr. Combs listened in to one of the regular teasing sessions that was conducted by my father’s colleagues, who were fellow waiters, about my father being “Spendthrift Farm’s Biggest Uncle Tom.” When Mr. Combs had heard enough, he quickly entered the kitchen and said, “Coleman is not Spendthrift Farm’s Biggest Uncle Tom. I am Spendthrift Farm’s Biggest Uncle Tom. And if Coleman and I stop Uncle Tomming, none of us will be working.”

My father often told me another Spendthrift story about how he personally welcomed former California Governor and Mrs. Ronald Reagan into Spendthrift’s mansion for a requested private meeting with Mr. Combs shortly after the Kentucky Derby. Apparently, Governor Reagan had approached Mr. Combs during the derby and asked if he could stop by the farm later to discuss purchasing any of his retired horses for his ranch in California. According to my father, after he settled Governor and Mrs. Reagan down in the living room with refreshments, he went upstairs to inform Mr. Combs that his important guests had arrived and were anxiously waiting to meet with him. Mr. Combs continued to talk on the phone long distance with New York bankers and other syndicate investment partners about the concerns related to the operations at Spendthrift. After more than an hour had passed while Mr. Combs remained on the phone, Governor and Mrs. Reagan decided to leave.

When Mr. Combs finally came downstairs, he was astonished to find that the Reagans had been too impatient to wait and had left. “Where are Ronnie and Nancy?” he asked my father. My father informed him that the Reagans had left because they felt they had been treated disrespectfully. According to my father, Mr. Combs shot back, “Forget’em. They wanted my ponies for nothing.”

Spendthrift Farm was a success because Leslie Combs managed his farm with a very deliberate, focused management style, combined with his seductive, Kentucky gentlemanly selling skills. Combs was ahead of his time when it came to syndicate financing in the horse business. He used innovative syndicated financing models that other breeding farms were not using. These models led to Spendthrift’s global success in producing winning thoroughbreds.

As my father would explain, Combs was maniacally focused on profitable results. Movie stars, elected officials, and anyone else who could not pay full, premium prices for his horses or help him meet his own personal and business objectives did not impress him. Business was personal with Combs. He would even make that clear to my father when he would see him serving his family members during a big horse sale instead of paying greater attention to prospective customers who were ready to pay full, six-figure prices for Spendthrift’s thoroughbreds. Combs once told my father, “Coleman, remember to always take care of our paying guests first and let my family get their own drinks. My family is as po’ as me. Dealing with po’ people will break you. As long as you live, always deal with your equals or your superiors because po’ people will break you!”

Combs was an early adopter and professor of the Cut the Crap and Close the Gap management approach. My father greatly admired Combs’s ruthless but gentlemanly style, and he embraced and deployed Combs’s aggressive, deliberate, results-oriented, impatient management approach in how he managed our farm, Coleman Crest, his family, and his own life.

My parents made me a Kentucky gentleman in the likes of Sam Coleman and Leslie Combs—proud, fierce, deliberate, impatient, sensitive, kindhearted, generous, tough, focused, resourceful, and never a quitter. This has enabled me to survive personal and professional setbacks, as well as to thrive in all my endeavors over the last forty-five years of my life.

CLOSE THE GAP TAKEAWAYS:

• We have the power to choose between being a victim or being an active participant in the American free enterprise system.

• We have the power to eliminate or provide access to the right people in our lives.

• No matter how difficult life can get, we can always focus on the controllables in our lives to achieve desired results.

• Successful people are deliberate and focused; very few people achieve desired results through luck.

• Carefully choosing your friends is important; we are the average of our five best friends.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

SEIZING THE MOMENT

Cut the Crap Principle 2: It’s always darkest before the dawn.

My ancestors were kidnapped from western Africa. They didn’t travel to America on a passenger ship like the Mayflower. Passenger ships were reserved for other immigrants who were headed to America to discover freedom from burdensome government and to claim a new beginning and new opportunities. According to my family’s verbal historian, Uncle Sam D. Coleman, my grandfather’s brother, my ancestors crossed the Atlantic on a slave ship headed for Spotsylvania, Virginia, only to discover slavery, oppression, and torture upon arrival.

When my ancestors arrived in Spotsylvania, there was no fanfare or well-wishers waiting to greet them at the dock. There were no photographers to take their pictures and no special transportation to take them to their final destination in the New World. What awaited them was a job that had no pay, crops to raise without adequate tools, and broken down, crumbling shacks, at best, for shelter.

Of course, “Coleman” was not my ancestors’ original name. Their African name was left at the docks of western Africa, and to this day, I still do not know my original African surname. Uncle Sam used to tell my mother all the time, “Cleo, we were Duersons before we were Colemans, and I don’t know why.” I recently connected the dots of Uncle Sam’s account of our history by discovering that my ancestors were given the name Duerson because they had been purchased upon their arrival to America by a wealthy family in Spotsylvania called the Duersons.

From what I have put together from the available information, combined with Uncle Sam’s recitation of our history, it is believed that my ancestors’ owners were John and Nellie Duerson. John and Nellie had five children: Thomas, Maria, Salina, John, and Mary. Mary left Spotsylvania and relocated to Fayette County, Kentucky (Lexington), in the late 1700s. She took several slaves with her, and they are believed to be my ancestors. When Mary arrived in Kentucky, she met and married a man named Coleman, and when her last name changed from Duerson to Coleman, so did my ancestor’s last name change to Coleman.

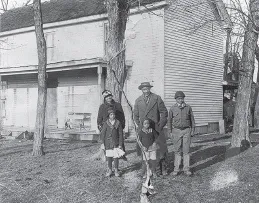

My great-grandfather James Coleman and his parents were slaves on a farm in Uttingertown, a small town eight miles from Lexington. My great-grandfather and his parents and siblings raised crops and livestock. They worked hard in the fields and in the kitchens for their slave owners. They closely observed how their wealthy slavemasters would leverage the value of their land to finance the purchase of farm equipment, supplies, and the education of their children. Much of the knowledge they picked up through observation and listening while serving their master’s dinner, they later employed to purchase property and change the lives of future generations.

According to research conducted by Kentucky Education Television (KET), “As the conflict over slavery heated up in the early 1800s, many abolitionists hoped that removing former slaves to Africa would further their cause by eliminating the need for whites and freed blacks to live and work together (a possibility only radicals entertained at the time). Some slaveholders were troubled by the morality of slavery and wanted to free their slaves—but only if the former slaves could then be sent far a...