![]()

CHAPTER

1

Why Smaller Can Be Better

From an emotional point of view, I certainly agree with the above statement. After all, elephants don’t bite, and they certainly look much better than fleas. Nevertheless, the flea can outperform the elephant ounce for ounce when it comes to physical power. Why is this, and does the same relationship apply to businesses?

To say that smaller companies can be more profitable sounds like heresy in an age that glorifies mergers and big business. Certainly, a larger company has more sales and typically more profit than a smaller enterprise, but what we usually don’t see is that the percentage of profit on sales of a very large enterprise is usually lower than that of a smaller or midsize competitor. In other words, small or medium-sized enterprises tend to be more efficient than their larger brethren. We may be better able to understand why this is by observing nature.

In nature, we see distinct differences in metabolism and work performed per given time between smaller and larger animals, all following so-called scaling laws, which define the rate of metabolism per unit of body weight between larger and smaller animals. These laws also govern the ratio between the surface area and the volume of a sphere. Could such scaling laws apply to businesses?

For modeling purposes, one could consider that, like the surface area of a sphere, the number of effective (i.e., profit-producing) employees— factory workers, for example—increases only to the square of the diameter, while the total number of employees (including production and office workers) increases proportionally to the cube of the diameter, much like the volume of the sphere, as I will explain later.

Hence, the larger the company gets, the smaller the number of effective employees compared to the overall number of workers. As a result, the rate of profit (the margin) decreases. Some companies are quite aware of this problem and try to correct it. Take General Electric, for example, whose net earnings increased from 11% to 12.6% of sales between 2004 and 2006. Yet, it could only do this by severely pruning its overhead expenses from 35.2% to 24.8 % of sales. Without this drastic measure, its 2006 earnings would have shrunk to only 2.2% of sales!

Scaling Factors in Nature

Scaling laws in nature regulate certain physical phenomena and behavior. Some of us have experienced dust storms driven by forty- or fifty-mile-per-hour winds. Luckily for us, the sand particles we feel are rather small, averaging less than five one-hundredths of an inch in diameter. Larger stones—those, say, one-half inch in diameter—stay on the ground. The reason is that the stones obey the 2/3 power scaling factor, or the “principle of similitude,” as D’Arcy Thompson3 called it in his 1917 book On Growth and Form.

“It often happens,” Thompson writes, “that of the forces in action in a system some vary as one power and some as another, of the … magnitudes involved.” Thus, returning to our sandstorm example, a half-inch-diameter stone weighs 1000 times more than the average grain of sand because the volume and weight vary to the third power.

However, the same stone exposes just 100 times greater surface area to the wind than the grain of sand because surface area varies only to the second power. Hence, the larger stone has only 10 percent of the surface area per ounce than the smaller one. The wind pressure must therefore increase by ten times to lift the larger stone!

Scaling factors affect the animal kingdom, too. A smaller animal has proportionally more surface area than a larger one, approximating the ¾ power-scaling factor (see explanation later). More surface area means that more thermal energy is radiated away from the surface of the animal, allowing for more work to be done in the form of muscle movement in a given time period. The transfer of heat through the radiation of thermal energy results from a temperature differential that provides the thermodynamic potential for work. The more efficiently heat is continuously radiated, the more power can be produced. A smaller body with a larger surface area does this more efficiently. This is also reflected by the differences in caloric requirements between different-sized animals. As stated by Thompson, a man weighing seventy kilograms consumes thirty-three calories per kilogram in a day, while a whale weighing 150,000 kilograms consumes about 1.7 calories per kilogram of its own weight per day.

People experience this power-scale relationship whenever we work in the tropics, where we find that our rate of work slows down considerably without the benefit of air conditioning. This means that it would take us perhaps twice as long to dig a ditch as it would up north (we perform the same work while using only half the power). The reason is that while we have an unchanged surface area, the temperature difference is lower between our body temperature and that of the surrounding air. Therefore, less thermal energy can be radiated and less muscle power produced. We would notice the same effect if our body surface were somehow reduced while our weight remained the same. This is exactly what happens to obese people even in moderate climates. Conversely, a very lean person has relatively more radiating body surface and therefore can produce more power per ounce of body weight, as photographs of the winners of the Boston Marathon illustrate.

To take another example, a mouse weighs about one ounce (0.0625 pounds) while a man may weigh 160 pounds. Assuming a ¾ power scaling factor, the surface area—and thereby the metabolic rate—of the mouse is about seven times greater than that of a human per ounce of body weight. D’Arcy Thompson and others have shown that the absolute work output (which is different than the power output) per ounce of body weight is roughly the same in all animals. It follows from the simplest definition of work (weight times distance) that, say, a flea, a man, or an elephant jumping seven inches straight up (a feat of which each is capable) will produce about the same work per unit weight.

This prompts the question: if the work done is the same, why then is the power output of smaller animals higher? Why is the metabolic rate higher in smaller mammals than in larger ones? The answer is that the former can perform the same amount of work much faster. Power is, after all, defined as work per unit time. Calories are converted into power, or work per second. In theory, 192,000 mice (which collectively would weigh the same as one elephant) would be able to move a given object a certain distance in one second, whereas it would take the elephant twenty-one seconds to do the same!

In another example, an elephant can carry a log weighing no more than about 1,100 pounds. Fifteen men can carry the same log (about seventy pounds for each) the same distance and in the same time as an elephant does. Yet it would take seventy men to equal the weight of an average elephant. This shows that a man is, pound for pound, about 445 percent more power efficient than an elephant.

Scaling Factors and Businesses

Just as Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” regulates markets, could the equivalent of natural scaling factors affect the profitability of businesses? Can it be that bigger is not necessarily better? All companies want to grow—a quite healthy thing to do—but how should they go about growing in the most profitable way?

Just as scaling factors apply to mice and elephants, could it not be that a smaller, homogenous manufacturing enterprise could be more power efficient, producing more widgets in a given time period than a larger counterpart?

Scaling laws, when applied to businesses, suggest that profit does not increase in linear proportion to sales growth or business size, but rather at a lesser, exponential rate. This rate could be defined by a power-scaling factor.

Using the ¾ power scaling factor, we could postulate that a company with 100 employees could produce the same number of widgets per employee as a competitor with 1,000 employees, but (100/1000)¾ / (100/1000) = 1.78 times faster. Expressed differently, six plants of the smaller variety could produce the same number of widgets per month as a single plant ten times as big. The reason for this is that more people in the larger plant work in jobs unrelated to the actual production of widgets, and each of the actual production workers in the large plant can only produce as many widgets in a given time period as their counterparts in the smaller plants. Expressed differently again, the larger plants have more overhead (and therefore higher transaction costs) due to the larger number of administrative workers. If this calculation holds true, then smaller, homogeneous enterprises (single, independent profit centers with their own management and accounting systems, and without any subdivisions or subsidiaries) will be more profitable, because they tend to have less overhead.

For our purposes, scaling laws may be usefully employed to help predict certain maximum size relationships within fully integrated (homogeneous) firms, although they certainly will not prevent the incompetent management of a small firm from resulting in a dismal profit picture. On the other side of the coin, a large enterprise might have an exceptionally large profit due to its quasi monopoly in a given business. Such cases should be excluded from this analysis.

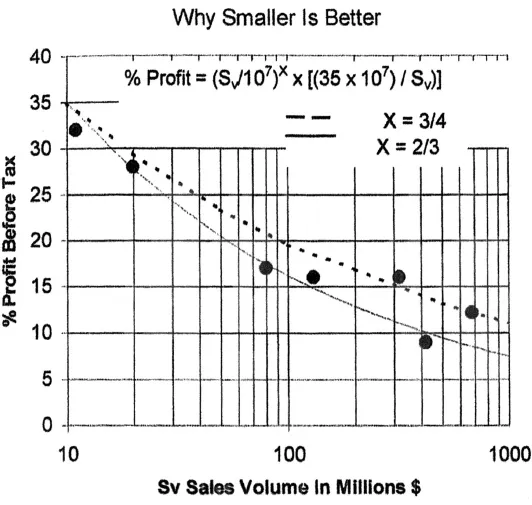

Figure 1-1

Figure 1-1 shows a typical relationship. Here I plotted the pretax earnings, expressed in percentage of sales against annual sales volume, of manufacturing companies that are in the same (or a closely related) market and that are either homogeneous organizations or independent divisions of larger firms. The reference values shown for the calculations were arbitrarily chosen to match the $10-million sales point at a 35 percent profit. A 2/3 and a ¾ power factor are used because both factors appear in nature.

The proposed equation that can be used to predict the percentage of profit as a function of sales at a larger firm using a known reference profit at a smaller (reference) firm with a given smaller sales volume is:

Here is an example: At a given company, we have $10,000,000 in sales and a 35 percent profit. What will the profit be at $100,000,000 in sales?

Note that this equation is not applicable if the growth in sales volume is primarily due to monetary inflation—that is, price increases. In those instances, there are no basic increases in personnel, and hence there is no profit deflator. This situation arises in large and mature companies where the profit level over the years stays basically constant, except for economically caused business disruptions.

In a January 12, 1999 New York Times article entitled “Of Mice and Elephants: A Matter of Scale,” it was stated that Max Kleiber, in the 1930s, found that metabolic rate scales with body mass not with the originally assumed power, but closer to the ¾ power. I therefore superimposed a curve following the ¾-power scale onto figure 1-1. The data points fall somewhere close or unknown in between. Nevertheless, both scaling factors clearly show a trend away from greater efficiency when a homogenous enterprise—or, for that matter, a conglomerate with equally growing divisions—expands. Note that the economy-of-scale effects do not appear in the data shown in figure 1-1 due to the lack of mass-produced items in this particular chosen industry.

Why, then, do larger corporations exist, and why do they make a decent rate of profit? This is becaus...