- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Army of the Roman Emperors

About this book

An illustrated history exploring the Imperial Roman army's many facets, including uniforms, weapons, buildings, and their duties.

Compared to modern standard, the Roman army of the Imperial era was surprisingly small. However, when assessed in terms of their various tasks, they by far outstrip modern armies—acting not only as an armed power of the state in external and internal conflicts, but also carrying out functions nowadays performed by police, local government, customs, and tax authorities, as well as constructing roads, ships, and buildings.

With this volume, Thomas Fischer presents a comprehensive and unique exploration of the Roman military of the Imperial era. With over 600 illustrations, the costumes, weapons and equipment of the Roman army are explored in detail using archaeological finds dating from the late Republic to Late Antiquity, and from all over the Roman Empire. The army's buildings and fortifications are also featured. Finally, conflicts, border security, weaponry, and artifacts are all compared, offering a look at the development of the army through time.

This work is intended for experts as well as to readers with a general interest in Roman history. It is also a treasure-trove for re-enactment groups, as it puts many common perceptions of the weaponry, equipment, and dress of the Roman army to the test.

Compared to modern standard, the Roman army of the Imperial era was surprisingly small. However, when assessed in terms of their various tasks, they by far outstrip modern armies—acting not only as an armed power of the state in external and internal conflicts, but also carrying out functions nowadays performed by police, local government, customs, and tax authorities, as well as constructing roads, ships, and buildings.

With this volume, Thomas Fischer presents a comprehensive and unique exploration of the Roman military of the Imperial era. With over 600 illustrations, the costumes, weapons and equipment of the Roman army are explored in detail using archaeological finds dating from the late Republic to Late Antiquity, and from all over the Roman Empire. The army's buildings and fortifications are also featured. Finally, conflicts, border security, weaponry, and artifacts are all compared, offering a look at the development of the army through time.

This work is intended for experts as well as to readers with a general interest in Roman history. It is also a treasure-trove for re-enactment groups, as it puts many common perceptions of the weaponry, equipment, and dress of the Roman army to the test.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Army of the Roman Emperors by Thomas Fischer, M.C. Bishop in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Dietrich Boschung

I | ICONOGRAPHIC SOURCES FOR THE ROMAN MILITARY |

1. Introduction

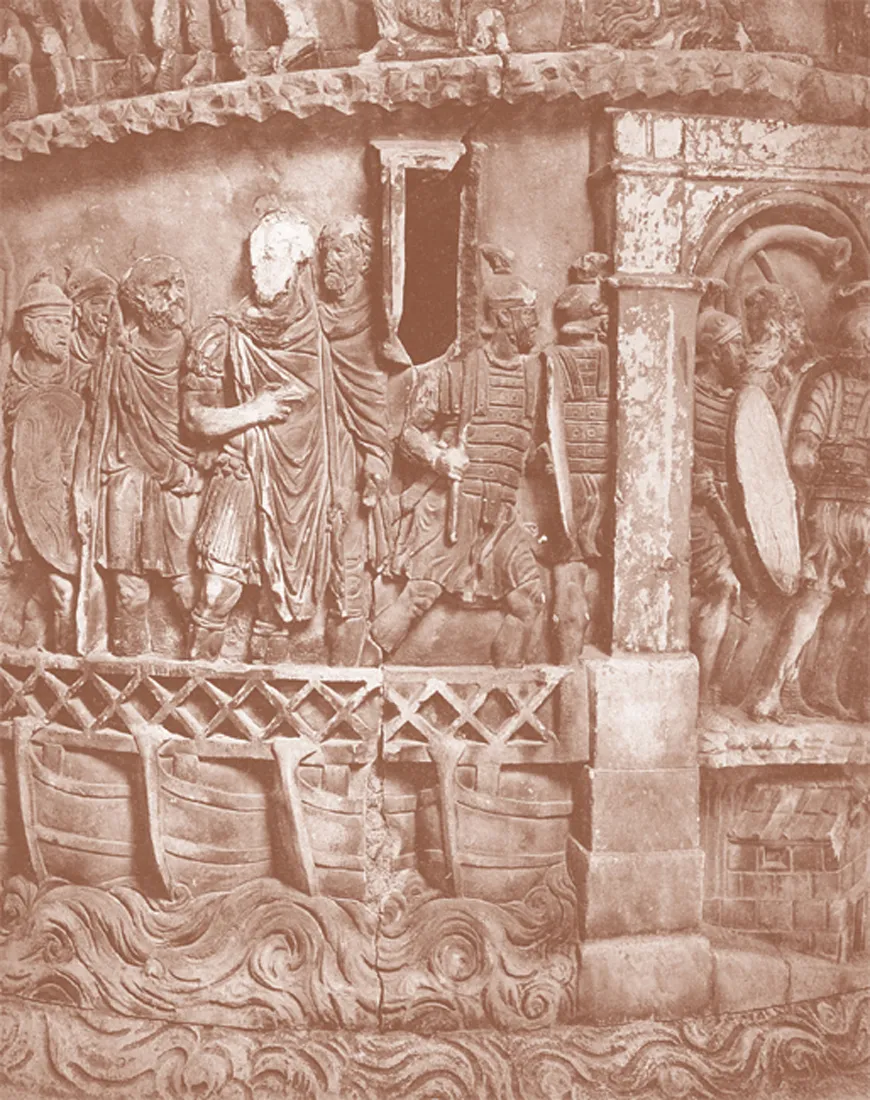

The numerous representations of the Roman military mainly fall into two categories: Roman funerary art, where soldiers are depicted on their gravestones, and state reliefs. They were not produced as an end in themselves, nor were they created with the intention of faithfully illustrating the structure or equipment of the Roman army, but for other reasons: with gravestones, a representative moment was always chosen, showing the depicted with his equipment to the best advantage.1 With state reliefs, the main purpose of the representations was to display the model behaviour of the exemplary commander in charge, i.e. the emperor. Among his main tasks was the provision of appropriate equipment for the soldiers, and especially the leadership of the army. Even if the emperor was not personally involved, he was ultimately responsible as holder of the auspices. The abundance of iconographic sources does not allow a comprehensive treatment of the subject here. Instead, I have restricted myself to a few, particularly informative, monuments. From these, it will become clear that there is no homogeneous convention for the representation of military themes in Roman art.

2. Republican representations

The frieze on the monument of L. Aemilius Paullus at Delphi

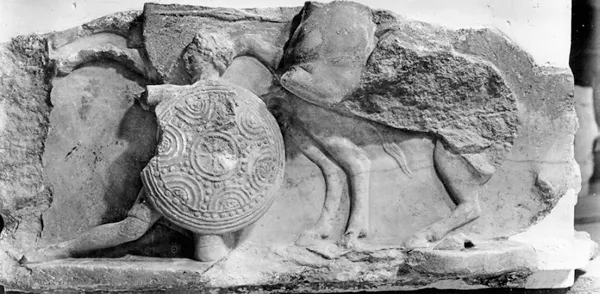

By the end of the 19th century, Théophile Homolle had already recognized the association of a four-sided frieze from the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi with the pillar monument of L. Aemilius Paullus, mentioned in several literary sources, and, as the subject of the representation, the battle between Macedonians and Romans at Pydna (168 BC).2 Further research has followed him in this,3 although some points are still very unclear. It seems the monument was initially started for the Macedonian king Perseus, the Roman imperator then appropriating the monument as booty after his victory.4

The subject of the frieze has been repeatedly associated with individual episodes of the Battle of Pydna,5 which is described in Livy and Plutarch. Homolle interpreted the striking representation of a fleeing horse without a bridle, occupying the middle of the long side (Fig. 12), with the help of literary information about the onset of battle.6 However, ownerless horses in flight are also common in mythological battle scenes, such as Amazonomachy representations from the 5th century BC through to the Roman Imperial period.7 At the same time, in contrast to the frieze in Delphi, the animal is usually associated with a fallen rider figure in these depictions and provided with a bridle. The motif of the riderless horse is thus presented in a different manner on the Paullus frieze and must be of particular importance, as has often been emphasized.8

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figures 12–15 Delphi, frieze from the pillar monument of Aemilius Paulus. Figures 12–13: eastern frieze; Figure 14: southern frieze (detail); Figure 15: western frieze (detail). Images: Cologne Digital Archaeology Laboratory

Other attempts to restore historically attested episodes of the combat in the frieze have been abandoned, however.9 Like the ownerless fleeing horse, some of the other figures also comply with the iconographic repertoire of mythological representations. These include horses with saddle blankets made from the fur of a predator (panther, lion), collapsed horses, and fallen mounts holding themselves upright with their front legs.10 The pose of a dying youth, with his head hanging back, crossed legs, and arm falling across his face, also corresponds closely with a traditional representational scheme in Greek art and is similar to the late classical theme of the dying children of Niobe.11

Given the traditional character types used, it is all the more striking that the warrior figures have contemporary armament. The frieze is supposed to represent an actual event, but uses preset iconographic elements for this, which are reassembled according to its intent. Topical references, especially the characteristic shields, identify the two sides here. Three round shields are depicted as Macedonian by their decoration of concentric circles and semicircles (Liampi 1998). They are consistently assigned to the losing side: the first shield is carried by a foot soldier standing behind a fallen rider and attacked by two Roman riders; a second soldier with a Macedonian shield is already forced onto his knee under the onslaught of the Romans (Fig. 13); and the third Macedonian shield covers a dead man (Fig. 14). The Macedonian troops are therefore hopelessly inferior in all phases of the fight. The shield of a fallen warrior is recognizable by its shape and distinct curvature as Macedonian. Only one Macedonian foot soldier is seen fighting, but showing his shield from the inside, so the decor is not visible. However, all the soldiers shown with the Roman scutum (oval shield) are attacking or fighting (Fig. 15). In four places on the frieze, they are to be found in the immediate vicinity of a falling or dead opponent.

Neither the scutum nor the ‘Macedonian shield’ have been exclusively carried by a single nation. In many cases, the Etruscans and Celts used the scutum, but the precise form used here is repeatedly found as the shield of Roman legionaries.12 Since they are also shown on Roman coins of the 3rd century BC and can be seen on the depiction of a trophy on the coins of Pyrrhus, these defensive weapons seem to have been regarded by both the Romans themselves and by their Hellenistic opponents as typical for the soldiers of Rome.13 On the Aemilius Paullus monument, the consistent distribution of the two shield forms, taken together with the inscription, suffice to characterize the triumphant side as Romans and the defeated as Macedonians.

The dramatic scenes of the Battle of Pydna reported by Plutarch and Livy are not recognizable in the representation on the frieze. Even the active role of the Macedonian cavalry there is in contrast to the historical accounts, whereby Perseus almost withdrew with the cavalry without engaging. The frieze avoids any hint of the menacing Macedonian phalanx, which had temporarily placed the Romans in serious difficulties. The elephants, whose attack initiated the Macedonian defeat,14 are also not included in the frieze. Only the fleeing horse, whose depiction is striking in its isolation and not motivated by later events, can be understood as a reference to the initiation of the battle. This can hardly be accidental because, according to the oracles, the manner in which the battle came about meant that the victory of the Romans was preordained by the gods.15 The frieze shows only a hint of units in close combat on this long side; the two adjacent sides indicate a melee with a more vigorous mixing of the parties. This can be reconciled with the historical accounts, whereby the breakup of the Macedonian phalanx was crucial to the outcome of the battle.

Above the inscription, the front of the frieze depicted the defeat of Perseus, heavily abbreviated:16 a Roman horseman and a Roman legionary storm over a dead man, clearly indicated as a Macedonian by his shield, in pursuit of fleeing enemies (Fig. 14). If the viewer followed the frieze to the adjacent sides and to the back, they could see how the defeat had occurred and that the Romans had started the fight in accordance with the omens. At no point in the battle are the Macedonian soldiers the equals of the Romans.

The Census Relief in the Louvre

In an entirely different context and in a different way, Roman soldiers appear on the Census Relief from Rome in Paris, dating back to the first half of the 1st century BC.17 It is divided into three sections, accentuated by the composition, the middle one of which occupies the most space (Fig. 16). It shows a figure-rich sacrificial scene, in which a rectangular altar is the centre of the action. Next to it, on the left and facing the front, a beardless warrior with helmet and armour holds a spear with his raised right hand and rests his left forearm on a round shield, while his hand grasps the hilt of a sword. His head is turned to the altar, with his right foot resting on its base. Neither the shield nor the armour correspond to contemporary forms of weaponry, so it must be a mythological figure who is accepting the sacrifice.

On the other side, a man is wearing a toga capite velato, i.e. pulled up over the back of his head, as was appropriate for the Roman ritual of sacrifice. His right hand holds a patera above the sacrificial face of the altar, over which an assistant is pouring wine. This is in preparation for a libation, which belongs to the bloodless part of the sacrificial ritual. Two musicians are also playing as part of the s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Translator’s Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I Iconographic sources for the Roman military by Dietrich Boschung

- Part II General remarks on the Roman army

- Part III Costumes, weapons, and equipment of the army from original archaeological finds

- Part IV The buildings of the Roman army

- Part V The development periods of Roman military history

- Part VI The Roman navy

- End matter