- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

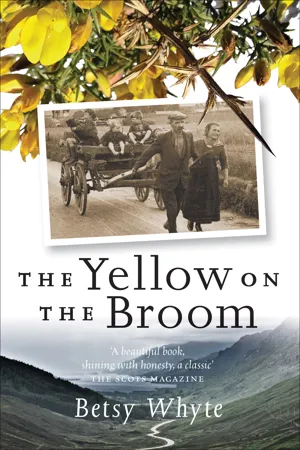

The Yellow on the Broom

About this book

This classic memoir of a Scottish woman's traditional nomadic family offers an intimate glimpse at girlhood in a bygone way of life.

A rare firsthand account of Scotland's indigenous traveler culture, The Yellow on the Broom has earned its place as a modern classic of Scottish literature. Here, Betsy Whyte vividly recounts the story of her childhood in flowing prose reminiscent of oral storytelling. Through the 1920s and 30s, she and her family spent much of the year traveling from town to town, working odd jobs while maintaining their centuries-old language and a culture.

Whyte's people were known by many names—mist people, summer walkers, tinkers, and gypsies. As their way of life became increasingly marginalized, they faced greater hardship, suspicion and prejudice. Together with her second memoir, Red Rowans and Wild Honey, Whyte's story is a thought-provoking account of human strength, courage, and perseverance.

A rare firsthand account of Scotland's indigenous traveler culture, The Yellow on the Broom has earned its place as a modern classic of Scottish literature. Here, Betsy Whyte vividly recounts the story of her childhood in flowing prose reminiscent of oral storytelling. Through the 1920s and 30s, she and her family spent much of the year traveling from town to town, working odd jobs while maintaining their centuries-old language and a culture.

Whyte's people were known by many names—mist people, summer walkers, tinkers, and gypsies. As their way of life became increasingly marginalized, they faced greater hardship, suspicion and prejudice. Together with her second memoir, Red Rowans and Wild Honey, Whyte's story is a thought-provoking account of human strength, courage, and perseverance.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

‘What’s that you’re doing, lassie?’

My mother’s voice startled me as I was sitting in the tent combing my hair—when I should have been away to work. The others had left over half an hour earlier.

Then I heard Mary’s voice answer Mother. ‘I’m just washing out some clothes.’ ‘I can see that you’re washing but, lassie dear, you can’t hang your knickers out like that there with all the men passing by looking at them. Look, lassie, double them over like this or pin that apron over them and they will dry just as quickly. If Johnnie comes home and sees your knickers hanging there, he will be your death.’

Mother came back into the tent muttering to herself ‘God knows what he was doing marrying a scaldie for anyway. You can put sense into them no way.’ Then she spoke to me. ‘Are you not going to any work today?’ ‘I’m just going, Ma.’

When I stepped out of the tent, I met Mary. She had not argued back with Mother but had done as Mother told her. ‘Are you going to the field?’ she asked. ‘Aye,’ I answered. ‘Are you?’

As the two of us made our way down the old road she asked me ‘Did you hear your mother at me again this morning?’ ‘Mother is only telling you for your own good. Remember the beating you got from Johnnie when you sat in front of the men with your legs apart?’ (Traveller men hate their wives doing things like that. A traveller woman would never do so, anyway.)

Mary was not a traveller. Johnnie, my mother’s nephew, had met her when he was working in Perth. She had worked in Stanley Mill and went into Perth some weekends, for her mother lived there. She had been cooped in the mill for five years and the fresh air and outside life since she married Johnnie had agreed with her. But she was a bit befuddled with some of our strange customs.

‘Ach, you’ll soon learn,’ I told her. ‘You’ve only been married four months.’ We were all really fond of Mary.

Soon we reached the field where several men and women were pulling turnips. My father, uncles and their wives, Johnnie (Mary’s man) and also a man called Hendry Reid who none of us was very fond of. Hendry was too soulless-hearted, having been known to kick and batter his wife and children—and horse when he had one.

This Hendry Reid was talking away as they worked. ‘That man is always ganshin’,’ I said to Mary. ‘Some of the men are sure to lose the head with him one of these days. He is always bragging about how he can get other men’s wives, and about what he done in the War, but my mother says that he hid himself in a cave in Argyllshire all the time of the War. His poor mother was trauchled to death carrying food for miles to him. Oh aye, he was a brave soldier!’

We picked up our hukes (sickles, if you like) and started to pull the neeps. Mary was not very good at it, but Johnnie helped her to keep up. Soon it was after midday and, although it was October, the sun was beaking down on us. Hendry was still ganshin’. My father and the other men and women could have seen him in hell. Nothing could have been more nerve-racking than his loud, squeaky, incessant voice.

2

Then Dad shouted to Mary and me. ‘You two lassies go down to that farm and see if you can get a drop of milk, and if you see the old keeper ask him for a seed of tobacco for me. I’ll have the water boiling for you coming back, so hurry up! Johnnie, you go for sticks—and Liza, you can look for some clean water.’ (Liza was Mother’s brother’s wife.)

It was more than a mile to the farm, so Mary and I walked quickly down the old road. ‘I could do with a smoke,’ Mary said. ‘Aye, and me too,’ I answered.

Then Mary looked startled. ‘Look over in that field. What are all they men doing over there?’ ‘That’s shooters,’ I told her. ‘Do you not see their guns? They are just stopped for a smoke.’ ‘Smoke!’ I said again. ‘What’s about asking them for tobacco?’ ‘I’m game if you are,’ Mary said. So we climbed through the paling and walked across the field. ‘They can only say aye or no,’ I told Mary.

There must have been about twenty men with plusfours, deerstalker hats and leather boots. As we drew near they stared at us. ‘What are you doing here, and what do you want?’ a huge man with a red mouser, and a face to match, shouted. He was holding a whisky flask in his hand, as were several of the others.

‘I wonder if any of you would have a wee bit tobacco to spare?’ I asked. ‘It’s for my father.’ I thought Beetroot Face was going to have a fit. ‘Get out of here before I put the dogs on you!’ The other men were all laughing. But one of them said ‘Wait a minute. Give this to your father’ and he threw a tin which landed at my feet. ‘Just take the tin with you,’ he said. I lifted it and took to my heels, Mary after me. We threw ourselves over the fence and collapsed, breathless and giggling, at the side of the old road.

‘He is a civil man, that one with the face like a harvest moon,’ I said. ‘You wouldn’t want for your supper if everybody was like him.’ Mary looked blankly at me and said ‘Eh?’ I sometimes forgot that she wasn’t a traveller, and didn’t understand this travellers’ habit of saying the opposite of what they meant.

‘Never mind,’ I said to her, opening the tin of tobacco. ‘This is not tobacco, it’s shag,’ I said. ‘Let me see.’ Mary took the tin. ‘It is tobacco. The very best of tobacco.’ ‘Well, I’ve never seen tobacco like that,’ I answered her, ‘but I’m going to make a fag with some of it anyway. Do you have a match?’ ‘No,’ she said. ‘Then we are as well worried as hung. We have tobacco now and no match. We’ll get one down at the farm.’

‘But wheesht, Mary! I hear something coming up the road. Come through the paling into the field and let it pass. It’s a car of some kind.’ It was a shooting brake. ‘Sit down Mary, and they won’t see us. Some of they gentry,’ I said, as it passed along the narrow road. ‘Come on and we’ll hurry to the farm for milk.’

The back door of the farm was wide open and the savour of cooking and baking nearly took the heart from me. I hadn’t as yet broken my fast. The farm-wife was a pleasant person. When we told her our errand she said ‘Aye, plenty, lassies—but it’s been skimmed. Give me your flagon and I’ll fill it for you.’

‘Did you come down the way?’ she asked, as she ladled the milk into the can. ‘Aye,’ I answered. ‘Then you must have seen the Duchess passing, in a shooting brake, and her two bonny wee lassies with her. The Duke is up there somewhere with the shooters. They say he is a good shot. He’s the Duke of York, you know, and he’s married to Elizabeth, one of the Bowes-Lyons from Glamis Castle. His father is the King,’ she went on.

‘Do you mean that one of they men shooting up the road is the King’s son?’ I asked. ‘That’s what I’m telling you,’ she answered. Mary and I exchanged glances. ‘Shaness, shaness,’ I whispered. The farm-wife was very pleased and excited at having seen the gentry. ‘The Duchess is likely away up with their lunch,’ she said. ‘My two laddies are away beating for them.’

‘Would you like a piece?’ she asked. She came out with two large pieces of still-warm scone. ‘Oh! Thank you very much, Missis.’ Mary rived into her piece but me, being a traveller, thought about my daddy pulling heavy swedes and without even a smoke. The scone would have choked me if I had eaten it past him. ‘If you don’t mind, Missis, I’ll take my piece up to my father. He is working just up the road a bit.’ ‘Och, just you eat it up, lass. I have plenty and I’ll give you some to take away with you.’ I sank my teeth into the scone. It was dripping with syrup and never, I thought, had I tasted anything better. ‘Well, goodbye Missis, and thank you kindly for being so nice to us. God bless you.’ ‘Away you go, lassies, it’s nothing.’

‘I’m not going up the road,’ I said to Mary. ‘Come on and we’ll cut across the fields.’ As we hurried over the fields Mary said ‘You forgot to ask for a match.’ ‘Oh, so I did,’ I answered. ‘I’m that worried about begging that tobacco. Don’t tell my daddy, mind.’

As we approached, Father asked sarcastically ‘Where did you go for the milk, to Kirriemuir? I’m sure I could have been in Inverness the time you’ve taken.’

Instead of answering him I took the tin of tobacco out of my pocket, opened it and held it out to him. ‘Where did you get that, lassie?’ ‘Lying on the ground,’ I said truthfully. ‘Look, boys!’ Daddy turned to let them all see it.

Oh, barry! They were so pleased. Few of them had seen tobacco like this before. ‘That’s the kind of tobacco the gentry smoke,’ Father explained to them. ‘One of them must have lost it. Maybe one of those who are shooting over there.’ (They had heard the gunshots from where we worked.) Soon they were all stuffing it into their pipes. Everyone had a clay pipe of his or her own. Yes, men and women.

‘Give Mary a wee puckle to make a fag, Daddy.’ ‘Better Mary would learn to smoke the pipe. They fags are not good for anyone,’ he said—passing Mary enough for a couple of roll-ups.

After a few minutes I asked Daddy for a draw of his pipe. ‘Just a wee draw, Daddy, to taste it.’ He took the pipe out of his mouth, wiped the shank with a corner of his shirt and handed it to me. This although I was only eleven years old at the time. Travellers are very fond of tobacco.

‘Come, wee woman, I think that should do you now.’ ‘If you filled a kettle with tobacco this lassie would smoke it to the bottom through the stroup, without a halt,’ he said to the others. ‘I always put my pipe and matches into my bonnet at the front of the bed at night, and I’ve seen her when she thought her mother and I were sleeping. She would creep cannyways over our feet and get the pipe and matches to light it, then put them back canny again after she had her wee draw. When she was only four years old!’

‘Now if a body had a drop tea . . .,’ Uncle Duncan said. ‘Who’s making the tea?’ The tea had been forgotten in the excitement over the tobacco.

3

The fire they had made was just embers and the water in the big black can had nearly all boiled away.

Liza had made a well over at the corner of the field. ‘Go and get some fresh water,’ Father said and I went to do as he asked.

‘Watch and no’ burn yourself,’ Liza shouted to me, as I went to get the black can. ‘Do you think I’m silly?’ I answered her. My mother had taught me the dangers of fire when I was still on the breast. (In those days they kept bairns on the breast long after they were running about.) I picked a couple of docken leaves and lifted the can from the fire, protecting my hands with the dockens. Then, throwing out the little water that remained in the can, I made my way down for fresh water—taking a cup with me to lift it in.

It was a lovely little spring. I wondered to myself how Liza could always manage to find water like this. She could be walking along the edge of a field, an old road or even a main road, and she would stop and say ‘I think there is clean water hereabouts.’ Then she would poke about with a stick and after a while lovely spring water would come bubbling up the stick like a fountain. Then she would dig with her hands, tearing away clods of earth and make a nice wee well, placing chuckie stones at the bottom of it. Soon the earth would settle down and you could lift the clean water.

This well was surrounded with watercress and already dozens of water spiders had found it. I marvelled at the speed with which these little creatures moved, darting out of the way of the cup as I lifted the water. Mother had often told me that they only lived on pure water.

Haws were hanging in bunches from a hawthorn tree. I must have still been hungry, as I pulled handfuls and ate them as I made my way back, spitting out the stones.

They had built up the fire again and were all sitting around it. The October sun had been warm while we worked but now, after sitting a while, you could feel the nip in the air.

Soon the water was boiling. Liza had made a big iron frying pan of skirlie (‘toll’ we called it) and was piling the skirlie on to slices of bread and handing them around. My other aunt, Bet, was dishing out the tea shortly after. She just threw the tea into the boiling water, lifted the can to the side of the fire then spooned sugar into it, finally adding the milk and stirred it up.

Mary had showed them the scones while I was away for the water. Four big thick scones cut into fours and spread thickly with home-made butter and cheese! They were shared equally.

‘She must be a nice woman, that farmer’s wife.’ ‘Aye, she is,’ I said, ‘and she has gallons of that beautiful skimmed milk.’ It was my Uncle Duncan, Liza’s man, who had spoken. He was my favourite uncle—tall, well-built and good-looking. Although his eyes were like indigo, his hair was black and curly. He never spoke a lot. He didn’t need to as he could learn more from one glance than most people could in an hour’s conversation.

‘The country people are awfully stupid in some ways.’ ‘How, Uncle?’ I asked. (We always said how instead of why.) ‘Well,’ he said, ‘there is that farmer’s wife. She will likely throw out all of that skimmed milk to the pigs and other animals. They think there is no value in it but, if they only knew, it is the best of the milk. The juice of the grass and herbs that the cow eats. The cream is only the fat of the cow.’

‘If Hendry doesn’t come, his wee drop tea is going to be stone cold.’ Someone else was speaking. ‘Where did he go?’ I ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Editor’s Note

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Chapter 31

- Chapter 32

- Chapter 33

- Chapter 34

- Chapter 35

- Chapter 36

- Chapter 37

- Chapter 38

- Chapter 39

- Chapter 40

- Chapter 41

- Chapter 42

- Chapter 43

- Chapter 44

- Chapter 45

- Chapter 46

- Chapter 47

- Chapter 48

- Chapter 49

- Chapter 50

- Chapter 51

- Chapter 52

- Chapter 53

- Traveller cant and Scots words used in my story

- Red Rowans and Wild Honey

- Plates

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Yellow on the Broom by Betsy Whyte in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.