- 437 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A biography that "restore[s] this remarkable young man to his rightful position as a leading figure in Scotland's contribution to our imperial history" (

The Scottish Review).

This is an astonishing true tale of espionage, journeys in disguise, secret messages, double agents, assassinations and sexual intrigue. Alexander Burnes was one of the most accomplished spies Britain ever produced and the main antagonist of the Great Game as Britain strove with Russia for control of Central Asia and the routes to the Raj. There are many lessons for the present day in this tale of the folly of invading Afghanistan and Anglo-Russian tensions in the Caucasus. Murray's meticulous study has unearthed original manuscripts from Montrose to Mumbai to put together a detailed study of how British secret agents operated in India.

The story of Burnes' life has a cast of extraordinary figures, including Queen Victoria, King William IV, Earl Grey, Benjamin Disraeli, Lola Montez, John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx. Among the unexpected discoveries are that Alexander and his brother James invented the myths about the Knights Templars and Scottish Freemasons which are the foundation of the Da Vinci Code; and that the most famous nineteenth-century scholar of Afghanistan was a double agent for Russia.

"An important re-evaluation of this most intriguing figure." —William Dalrymple, bestselling author of The Anarchy

"Murray's book is a terrific read. He has done full justice to the life of a remarkable British hero, without ignoring his faults." — Daily Mail

"A fascinating book . . . his research has been prodigious, both in libraries and on foot. He knows a huge amount about Burnes's life and work." — The Scotsman

This is an astonishing true tale of espionage, journeys in disguise, secret messages, double agents, assassinations and sexual intrigue. Alexander Burnes was one of the most accomplished spies Britain ever produced and the main antagonist of the Great Game as Britain strove with Russia for control of Central Asia and the routes to the Raj. There are many lessons for the present day in this tale of the folly of invading Afghanistan and Anglo-Russian tensions in the Caucasus. Murray's meticulous study has unearthed original manuscripts from Montrose to Mumbai to put together a detailed study of how British secret agents operated in India.

The story of Burnes' life has a cast of extraordinary figures, including Queen Victoria, King William IV, Earl Grey, Benjamin Disraeli, Lola Montez, John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx. Among the unexpected discoveries are that Alexander and his brother James invented the myths about the Knights Templars and Scottish Freemasons which are the foundation of the Da Vinci Code; and that the most famous nineteenth-century scholar of Afghanistan was a double agent for Russia.

"An important re-evaluation of this most intriguing figure." —William Dalrymple, bestselling author of The Anarchy

"Murray's book is a terrific read. He has done full justice to the life of a remarkable British hero, without ignoring his faults." — Daily Mail

"A fascinating book . . . his research has been prodigious, both in libraries and on foot. He knows a huge amount about Burnes's life and work." — The Scotsman

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Montrose

Alexander Burnes has no grave and no memorial. When hacked to death in the Residence garden in Kabul, the bodies of Alexander and his younger brother Charles disappeared. Unlike other victims of the uprising, no severed body parts were hung in the bazaar by triumphant Afghans or paraded on spears to taunt British prisoners. Burnes’ boss, William Macnaghten, was to be displayed in parts through the city, but somehow, a year of vicious war later, enough bits of him were reassembled by the British for a burial ceremony. There is no definite evidence of what happened to the remains of Alex and Charlie, and nobody in the British army tried to collect them.

Nor did their family put a plaque in the local kirk of Montrose. This is something of a mystery. The churches of the United Kingdom are replete with memorial tablets to those who fell in the Empire’s wars, many very much less distinguished than Lieutenant Colonel Sir Alexander Burnes KCB, FRS, FRGS, Légion d’Honneur, Knight Commander of the Royal Dourani Empire. Not to mention, a greater honour than all that in Alex’s own estimation, great-nephew of Robert Burns.

Montrose is a bustling and handsome market town on the East Coast of Scotland, with the county of Angus as its hinterland. Services to the North Sea oil industry have attracted corporate outposts and a technical training industry and given new life to its port. It is neither sleepy nor backward looking, and retains virtually no memory of Alexander Burnes.

This is a shame because Burnes never forgot Montrose, and he had the Montrose Review sent out to him in Bombay, Bhuj and Kabul. He was Montrose through and through. His father, brother and grandfather were all Provost and his mother’s cousin was the minister.

The Burnes family had lived in north-eastern Scotland for at least 200 years. We know rather a lot about Alexander Burnes’ ancestors because, being also Robert Burns’ ancestors, they are the second most studied family in Scottish history. Alexander’s brother James was to become an obsessive genealogist, for the most curious of reasons.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century the Burnes family had been tenant farmers on the fertile coastal lands of Earl Marischal Keith; sufficiently well-to-do to intermarry with junior brides of the Keith family.1 Unfortunately, as the hereditary leader of the King’s military forces in Scotland, the Keith raised the standard of Jacobite rebellion in 1715, when Westminster proclaimed the German and unpleasant but Protestant George I as the replacement for the last Stuart monarch, Anne. The Burnes family followed the Stuarts loyally in both 1715 and 1745, and suffered despoilation and deprivation as a result. As Robert Burns put it:

What they could, they did, and what they had, they lost: with unshaken firmness and unconcealed Political Attachments, they shook hands with Ruin for what they esteemed the cause of their King and their Country.

Robert Burns’ view of family history tallies exactly with the later manuscript researches of James Burnes, who specifically mentions Robert Burnes of Clochnahill as fighting at Sheriffmuir and Fetteroso.2 Some writers on Robert Burns have dismissed his Jacobite ancestry as romantic speculation. But it is now plainly understood that the majority of Jacobite volunteers were in fact from north-east Scotland rather than the Highlands proper, and were not Roman Catholic.3 Their motivation was primarily nationalist.4 If the Burnes family were not out, who would be? Besides, as chief tenants of Earl Keith, they would have been expected to follow him into the field.

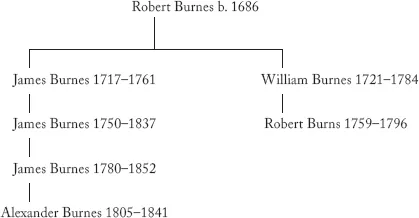

The diagram shows Alexander Burnes’ relationship to Robert Burns.5

Alexander’s eldest brother was also a James Burnes (b. 1801). Historians have previously made the relationship between Alexander and Robert closer, claiming Alexander Burnes’ grandfather and Robert Burns’ father as brothers. This seems to have been done by collapsing James Burnes 1750–1837 and James Burnes 1780–1852. This mistake is easily made as father and son worked for thirty years in the family law firm, both were on Montrose town council, and one married a Miss Greig and the other a Miss Gleig.6

The poet was the first in the family to drop the ‘e’. His father William moved to Ayrshire where the surname was usually spelt ‘Burns’, and that is probably why Robert changed. William had left Angus when his father’s farm at Clochnahill failed and, via Edinburgh, moved to Ayr and life as a landscape gardener and farm improver. Robert Burnes – as his baptism record spells it – the future poet, was born in Alloway on 25 January 1759.7

On leaving Clochnahill, William’s brother James moved to Montrose, where he worked as a builder and achieved respectability as a member of the town council. His son, also James, studied law in Edinburgh8 and eventually established his own law firm in Montrose, and set his son James on the same path. This James, b. 1780, was a contemporary at Montrose Academy of Joseph Hume and James Mill; after studying law at Edinburgh he became apprenticed to his father and entered the family law firm.

In 1793 James Burnes (b. 1750), Writer to the Signet, built a house at Bow Butts, a name denoting the archery range. The Burnes house today stands neglected and on the buildings at risk register.9 It is a solid home in a vernacular take on classical architecture. The ceilings are low and the building a little squat, hunkered down against the icy winter blasts on this north-eastern coast. Extended later, in Alexander’s boyhood it had four bedrooms, three reception rooms and a kitchen. In its day, Bow Butts would have been one of the major houses of Montrose.

I commissioned an architect’s report in 2008 which commences: ‘The house is in a fairly dilapidated state with many areas of water penetration and broken and built-up windows. There is quite a bit of internal damage and mild vandalism and there are many dead pigeons […]’10 Most of the architectural features have been robbed out. All the land with the house was sold, and later buildings have been constructed right up against it. The Provost lamp11 which is recorded as being above the front gate has been removed. The house is not listed for protection.

James (b. 1750)’s wife, Anne Greig, died in 1796. In 1800 his nineteen-year-old son brought home a seventeen-year-old bride, Elizabeth Gleig, daughter of the Provost of Montrose, to his widowed father’s home, shared also with the groom’s three sisters and brother. None of these married or lived past thirty. They remained in the home, which James and Elizabeth started to crowd further with many children. Alex was to reminisce that his bedroom was the cupboard under the stairs.12

On 12 February 1801, seven months after her marriage, Elizabeth Gleig gave birth to non-identical twins. They were baptised James and Anne. Anne survived baptism only a few days. James grew up to become a doctor.

In February 1802 Elizabeth gave birth to another healthy son, named Adam, who was to become the third generation in the family law business. In 1803 Robert arrived; he died aged twenty-two. No children were born to Elizabeth in 1804, but on 16 May 1805 Alexander, our hero, came into the world.

He was premature and baptised quickly in case he did not survive, but grew into a robust child. He was to have plenty of company; the fifth surviving sibling, David, was just a year younger and their first surviving sister, Anne, brought what must have been a welcome feminine touch to the brood. One year later she had a sister, Elizabeth, to keep her company. The next year, 1810, they were joined by Jane. In 1812 another boy came along, Charles, of whom Alex, seven years older, was extremely fond. It was 1815 before Cecilia joined the family. William was born in 1818, and Edward in 1819.

So when Alexander left home in 1821 he had eleven living siblings, while his grandfather also lived at home with with his mother and father. His three unmarried aunts, who had lived with them, had all died in their twenties, which gave Alexander early acquaintance with death. Yet another brother, George was born in 1822, though, with the two toddlers, William and Edward, he died the same winter. A final sister, Margaret, born 1824, also only lived a few weeks.

As Alexander grew up, his father was at the centre of the social life of Montrose. He had married the daughter of the Provost. He joined Montrose burgh council on 11 December 1817, became Chief Magistrate on 23 September 1818 and was himself elected Provost in 1820 and re-elected in 1824.13 Scottish burghs were extremely corrupt and literally self-perpetuating, the only voters for a new council being the councillors. But the Montrose election was the only exception in Scotland for fifty years, the burgh having obtained a royal warrant for election by all burgesses – a much wider but still limited franchise. James Burnes eventually became Justice of the Peace for Forfarshire, and ‘took a leading part in all the agricultural and municipal improvements which were effected in the eastern district of his native county’.14

Here he is Secretary of the Central Turnpike Trust, meticulously keeping the board minutes and accounts of the project to build a new high road through Angus to Dundee. Here he is Secretary of Montrose Circulating Library, persuading the publisher Constable to provide books at trade prices.15 On 1 February 1799, when the Montrose Loyal Volunteers are raised to fight against any Napoleonic invasion, the General Order commanding their establishment is recorded in the meticulous hand of James Burnes, their newly commissioned adjutant.16 He was Master of St Peter’s Lodge of Freemasons, as had been his father before him.17 Alex Burnes’ family were local movers and shakers.

James also played a wider political role in electing the town’s Member of Parliament. A single member represented the burghs of Montrose, Arbroath, Forfar and Brechin, and again the only electors were the councillors of each burgh. There was therefore much political negotiation, fixing and corruption. The town’s democratic sympathies were generally radical, and fifteen-year-old Alexander enthusiastically recorded in his diary the jubilation at the acquittal in 1820 on adultery charges of Queen Caroline: ‘A most brilliant illumination […] on the ground of the glorious triumph the Queen had obtained over her base and abominable accusers.’ Support for the Queen against the King had become a symbol of radical and anti-monarchical feeling.

The agricultural improvements in which Provost Burnes was involved increased productivity but had profound social effect. In Forfarshire adoption of turnips and clover as rotation crops led to an increase in cattle on previously arable land, raised in the hills to the west then fattened in the lowlands. This led to better manured and more intensively farmed soil and increased grain production. It also meant the end of the run-rig system and the removal of cottars, who lost their smallholdings amidst the inclosure of commonalities. In 1815, fully two-thirds of Scotland was common land, but it was to be grabbed quickly18 by the aristocracy. Lawyers like James Burnes were central to agricultural ‘improvement’, because their role was to dispossess cottars and traditional tenant farmers – who had very little protection under Scots law – and to execute inclosure. The Ramsay family’s Panmure and Dalhousie estates were leading examples of agricultural improvement, and it was chiefly for the Ramsays that James Burnes undertook this work. The Burnes/Ramsay relationship was to extend to India and to Freemasonry and forms a major subject of this book.

The most important buildings in the Montrose lives of the Burnes family are still there, and it is instructive to walk around them. In one sense their world was highly circumscribed. Provost Burnes could walk past his home, his legal office, his kirk, his town hall, his Masonic Lodge in under three minutes. At the bottom of the Burnes’ large walled garden was Montrose Academy, where the children went to school, and next to it the links where they used to play.

Yet in another sense this little world of Montrose was extraordinarily wide. In that three-minute walk, Provost Burnes would pass the homes of the Ouchterlonies, the Craigies, the Ramsays, the Leightons and the Humes. Every one of these families had sons serving as military officers in India. Their residences, behind severe stone exteriors, were ornamented with oriental hardwoods, high ceilings, fancy plaster-work and marble. Their contents were bought with remittances from India and profits from Arctic whalers and Baltic timber, jute and tobacco vessels that lined Montrose’s wharves. In the year of Alex’s birth 142 vessels were registered to Montrose, totalling over 10,000 tons. The town had five shipyards. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface: Historian, Interrupted

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Montrose

- 2 A Rape in Herat

- 3 Scottish Patronage, Indian Career

- 4 A Griffin in India

- 5 Dawn of the North-West Frontier

- 6 The Indus Scheme

- 7 The Shipwreck of Young Hopes

- 8 The Dray Horse Mission

- 9 The Dazzling Sikhs

- 10 Rupar, The Field of the Cloth of Cashmere

- 11 Journey through Afghanistan

- 12 To Bokhara and Back

- 13 The Object of Adulation

- 14 Castles – and Knights Templar – in the Air

- 15 To Meet upon the Level

- 16 Imperial Rivalry in Asia

- 17 While Alex was Away

- 18 Return to the Indus

- 19 The Gathering Storm

- 20 Peshawar Perverted

- 21 The Kabul Negotiations

- 22 Stand-off

- 23 ‘Izzat wa Ikram’

- 24 Regime Change

- 25 Securing Sind 254

- 26 The Dodgy Dossier

- 27 Kelat

- 28 A King in Kandahar

- 29 Death in St Petersburg

- 30 Ghazni

- 31 Mission Accomplished

- 32 Kabul in Winter

- 33 Dost Mohammed

- 34 Discontent

- 35 Dissent and Dysfunction

- 36 Death in Kabul

- 37 Aftermath

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Illustrations

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Sikunder Burnes by Craig Murray in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.