- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

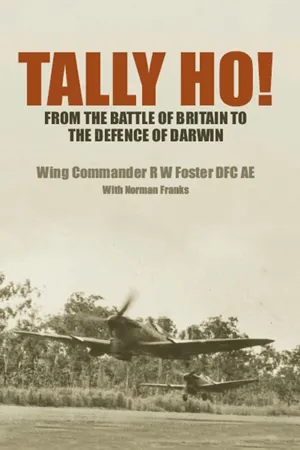

A memoir of the life and World War II service of Battle of Britain veteran, RAF fighter pilot Bob Foster.

Bob Foster's flying years began shortly before WWII, when he learned to fly with the RAFVR. Called up for war service in September 1939, he completed his training and was posted to 605 Squadron, equipped with Hawker Hurricanes. By early September 1940 he and his Squadron were in the thick of the air fighting over southern England, operating from Croydon.

Surviving the Battle, he later became an instructor, but shortly after joining 54 Squadron, which had Spitfires, he and his unit were sent to Australia to defend the Darwin area from Japanese incursions. Awarded the DFC for his efforts, he returned to the UK and was given an assignment with a RAF public relations outfit, ending up in Normandy within three weeks of the invasion of 1944.

Often serving right up in the front lines, Bob

saw the war at very close hand, and then quite by chance became one of the first, if not the first, RAF officer to enter Paris with the liberating French army, and again, by chance, was in General de Gaulle's triumphant procession down the Champs-Élysées.

His memoir is an entertaining collection of stories and reminiscences of two distinct areas of WWII, which also shows how luck often shaped the lives of the fighter pilots involved. Bob Foster later became a successful sales manager with Shell-Mex and BP, as well as serving with the Royal Auxiliary Air Force. He now lives with his wife Kaethe near Bexhill in East Sussex.

Bob Foster's flying years began shortly before WWII, when he learned to fly with the RAFVR. Called up for war service in September 1939, he completed his training and was posted to 605 Squadron, equipped with Hawker Hurricanes. By early September 1940 he and his Squadron were in the thick of the air fighting over southern England, operating from Croydon.

Surviving the Battle, he later became an instructor, but shortly after joining 54 Squadron, which had Spitfires, he and his unit were sent to Australia to defend the Darwin area from Japanese incursions. Awarded the DFC for his efforts, he returned to the UK and was given an assignment with a RAF public relations outfit, ending up in Normandy within three weeks of the invasion of 1944.

Often serving right up in the front lines, Bob

saw the war at very close hand, and then quite by chance became one of the first, if not the first, RAF officer to enter Paris with the liberating French army, and again, by chance, was in General de Gaulle's triumphant procession down the Champs-Élysées.

His memoir is an entertaining collection of stories and reminiscences of two distinct areas of WWII, which also shows how luck often shaped the lives of the fighter pilots involved. Bob Foster later became a successful sales manager with Shell-Mex and BP, as well as serving with the Royal Auxiliary Air Force. He now lives with his wife Kaethe near Bexhill in East Sussex.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tally Ho! by R W Foster,Norman Franks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Just a Lad from London

I was born into what might be called a military family. My paternal grandfather, William Foster, himself the son of a soldier, had at the age of 13 years and ten months, enlisted in the 36th Regiment of Foot at Peshawar, India, now Pakistan, in 1869 and spent altogether 26 years in the service. In 1885, whilst stationed in Jersey, he married my grandmother Frances Boyd Fasson, and when he retired from the army, they set up home in England, initially living in Broad Street, Holborn, London. They had three sons; William Thomas – my father [pictured overleaf], Robert Henry and Albert George. William and Robert both joined the army, while Albert went into the Metropolitan Police Force. Some time later, my grandparents moved to Sangora Road, Battersea, off St John’s Hill, where my grandfather died in 1916.

Somewhere along the way, Robert met a young lady named Violet, who came from a farming family in Crowborough, Sussex, and just prior to the start of the 1914-18 war they became engaged to be married. Robert, a regular soldier, went to France with the British Expeditionary Force, as a lance-corporal with the 2nd Worcestershire Regiment, as soon as the war began in August 1914. He saw a good deal of action in those first weeks, but his luck ran out on 20 October, during what was later called the First Battle of Ypres, and he was reported missing, believed killed. He is remembered on the Le Touret Memorial, some five miles north-east of Béthune. Presumably Violet had also met my father when she was engaged to Robert, and subsequently, following Robert’s death, their relationship blossomed after his eventual return from France.

My father, William Thomas Foster, had been a regular army man from 1901, having joined as a boy soldier with the Royal Engineers, did his twelve years, and came out in 1913. He too joined the police force, but was called back into the army with the advent of World War One on 14 August 1914.

He went to France with the REs but was wounded in 1915 whilst laying wire between front line trenches and ‘no-man’s-land’, also somewhere near the Belgian town of Ypres – or Wipers as he and other WW1 soldiers would have called it. Due to the ferocity of the action at the time, he was forced to lay out on the edge of no-man’s-land for some 48 hours before his mates could bring him back in, and as a result of his injury he had to have his right leg amputated. This had to be taken off very high which made it then impossible to fit a prosthetic – artificial leg – so this necessitated him having to get around on a pair of crutches for the rest of his life. He did however receive the Distinguished Service Medal for his bravery, of which he was very and rightly proud, although I personally have no doubt he would have preferred the leg to his medal.

He married my mother Violet (Vi) in 1919 and they lived in Mysore Road, Battersea, which for those who do not know the area, runs from Lavender Hill to Clapham Common, North Side, adjacent to Elspeth Road. When the time came for me to make my entrance, my mother went into a nursing home situated in nearby Lavender Gardens, just the other side of Elspeth Road, and she was delivered of me on 14 May 1920. I was to be their only child and was given the name of Robert in memory of my father’s late brother. Battersea, of course, was a very different place then, than it is today.

Oddly enough we later moved to Lavender Gardens so remained near to two of London’s famous landmarks, Clapham Junction railway station and Battersea Power Station with its four huge chimneys. In my early youth there were two great play areas very conveniently placed for me, Clapham Common and Wandsworth Common, while London itself was just minutes away by train or just a little longer by bus.

Being educated in London in the 1920s and 1930s was a straightforward affair. Although the London County Council, which controlled schools was strongly Labour, pupil selection was the order of the day. At 11 years of age all children in council schools took an examination. Those who failed stayed on in the elementary school system till the age of 14, at which time they were sent out into the wide world. It sounds strange, but in those days there were plenty of jobs to be had in shops, offices and factories for these youngsters. Those who did slightly better in the exams went to a central school till they were 15, and were then sent out to make a living for themselves. The rest who had obviously achieved far better results were sent on to secondary grammar schools.

I was lucky enough to attend one such school, the Henry Thornton Grammar School, a newly built establishment on the south side of Clapham Common, and better still, it was within walking distance of home.

The name of the school came from the grounds of the house on which it was built, the former home of Sir Henry Thornton, who in the early 1800s, was one of the so-called Clapham Sect, a body of philanthropists and leaders of the anti-slavery movement. Men such as Cavendish, Cook, McCauley, Pepys, Stephens, Wilberforce, were all part of this sect.

The school was good enough to provide me with a wonderful education. I like to think I did fairly well, if not academically, then certainly as far as sport was concerned. I became captain of games, played lacrosse for the school, and the south of England against the north, enjoyed football and I was also quite a good runner. In 1936 I won both the 220 and 440 yards championships, also setting up a school record. In tennis I won in the doubles, the school fives and the Victor Ludorum.

This idyllic situation continued until 1937 by which time, having passed my matriculation and so on, I decided against further education and at the tender age of 17, left to become employed by the Shell-Mex company, at their offices in Shell-Mex House in the Strand, London, as a very junior office boy. Not that it was my own idea. In fact I had no comprehension of what sort of life lay ahead of me nor of what I wanted to do in it, so it was a comfort when someone else decided for me.

My father’s brother Albert had by this time progressed with the police and was number two in Special Branch at Scotland Yard, and with that sort of job and an influential circle of friends and associates, he knew just the right people to ask about a job for his young nephew. One of these was Sir Robert Waley Cohen, the managing director of Shell, and I remember being instructed to put on my best bib and tucker and go with my uncle to lunch at the National Liberal Club in Whitehall, where an informal meeting was to take place. The lunch and casual interview must have gone well for a few days later I received an application form and was told to attend Shell-Mex House for a formal interview. From this I was taken on as an employee.

In those days one came into Shell, certainly at my level, as a very junior boy, starting off by taking messages around, going out and doing all manner of tasks for the company directors and board members. All very basic but to someone of my tender years, not totally unexciting and with a bit of freedom thrown in to discover London’s west end. This went on for a while and I had obviously kept my nose clean and not been found particularly wanting, so I was sent along to what was then called the buying department and given a job which I found quite interesting. I was lucky in that the boss of the department, Mr Anderson, who in the Great War had been in the Royal Flying Corps as an engineer, was very keen on young people joining the military or territorial services, no doubt alive to the worsening situation in Europe in the late 1930s.

In the same department I had made friends with Dick Morley, and in early 1939, following on from the time of Munich and Neville Chamberlain’s ‘peace in our time’ display after his talks with Herr Hitler in Germany, Dick and I made a decision. We thought that if there was indeed going to be a war, which despite Chamberlain, seemed almost inevitable, neither of us wanted to await being conscripted into something where we might have no choice but to accept. Dick had decided it would be a good idea to be an officer, so off he went and volunteered for service with the HAC – Honourable Artillery Company. This seemed to me to be far too noisy an outfit with guns going bang all over the place and in any event I had no desire to become some second-lieutenant in the army, feeling that this was the worst job anyone could have. So I took myself off to Adastral House, in Kingsway, which was within a short walk from Shell House, and applied to join the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve.

It wasn’t long before I had the usual short, sharp medical, had my chest tapped, ears looked into, and after the obligatory trouser-dropping and cough, was moved onto the next stage. This consisted of some rudimentary tests, one of which was being swung round in a chair to see if I would become giddy and fall over. Having got over that hurdle without falling down, I suddenly found myself accepted into the RAFVR.

As can be imagined, Mr Anderson was very pleased at my acceptance and managed to get the Shell bosses to allow me two months paid leave of absence in order to have some ab initio flying training, which consisted of a short course which was run by the short service commission people. This led me to doing 50 hours of pre-war flying which became the start of my flying career. I had always been keen on aviation as many young lads in the 1930s had been, reading stories of air battles over France in WW1, and of men and women pioneers who had started to open up the Empire by flying to all parts of the compass in small, light aeroplanes, and being thrust into the forefront of the news with little less than hero status. However, equally like those many youngsters, I had never been anywhere near an aeroplane in my 19 years.

On 1 May 1939, just a couple of weeks away from my 19th birthday, I duly reported to Anstey, situated just outside Coventry, and to 9 E&FTS, where the ab initio courses were being held, and run by a civilian company called Air Service Training. The chief flying instructor (CFI) was Flight Lieutenant J B Veal RAFO. Their job was to train short service commission types and they had also agreed to take in a certain number of VR types on their courses.

So I reported to Anstey, where I found there was a mix of about 50/50 of VR and SSC people on the two-month course. We joined the VR as AC2s but we were then made sergeants two days after our arrival. This must have annoyed the poor old regular NCOs in the RAF who had struggled for years of peacetime service at home and abroad, the lucky ones having dragged themselves up to corporals, sergeants or even flight sergeants, to find all these ‘wet behind the ears’ novices, suddenly on a par with them, or for the corporals to be outranked by us. Still, there was little they could do about it, and as the old saying goes, if you can’t take a joke you shouldn’t have joined!

I remember vividly my first flying day. We had been issued with flying clothing and there we were, all togged up and raring to go. With some anticipation we awaited the arrival of our flying instructors who were about to take us into the blue and make airmen of us all. Suddenly this chap came into the crew room and called for Sergeant Foster. I held up my hand and walked towards him. This was, I later discovered, Pilot Officer B R Tribe RAFO (Reserve of Air Force Officers) – pictured above in the front cockpit with me behind.

‘Ah, Sergeant,’ he began, and noting that I was an NCO continued, ‘you’ve probably done a bit of flying, yes?’ I told him that I had never been in an aeroplane in my life. He was visibly deflated.

‘Oh, Christ,’ was his response, then with a wave of his hand merely said, ‘Come on,’ and turned for the door.

The aeroplane in which I was about to ascend into the late spring day was an Avro Tutor, a single-engined biplane used by the RAF as an elementary trainer. It had an Armstrong Siddeley Lynx IVC engine, of around 220-240 horse-power and had been the replacement trainer after the old WW1 design, the Avro 504N, since 1932. Its maximum speed was 122 mph, it could cruise at 105 at 1,000 feet, was able to reach the dizzy height of 16,200 feet and stay aloft for nearly three hours. Of course, all this was lost on us and me in particular. All I saw as I manfully strode towards it, dutifully a couple of paces behind Pilot Officer Tribe, was a silvery looking machine with two wings looking like something from the films Dawn Patrol or Hell’s Angels and aware that this man who was going to show me how it worked, was far from impressed at having this complete novice in his care.

However, I survived my first flight, which I enjoyed immensely, and knew that so long as I didn’t break anything (me included) I was going to like this flying game. Pilot Officer Tribe did his job well and got me solo in about nine hours, but it wasn’t a happy relationship. We just didn’t get on and it seemed that everything I did was wrong, and as soon as I soloed, he very quickly handed me over to someone else. It was no doubt the system that newly soloed pupils went onto another stage with another sort of instructor, but there was certainly no love lost and we were both happy to divest ourselves of each other.

It had not helped when I blotted my copy-book with him after he sent me off on my third or fourth solo, for some local flying. I was so happy and absorbed flying around on my own that after about half an hour I looked down and about, only to discover I hadn’t got the slightest idea where I was. There were no recognisable landmarks, nothing that looked even remotely familiar. In short, I was lost.

There was only one option for me, and that was to find a nice big, flat field where I could put down without smashing anything, and ask someone where the heck I was. This I proceeded to do, although it was then impossible for me to restart my engine, so although I soon found where I was, I had then to telephone the aerodrome for help.

Tribe and the CFI, Flight Lieutenant Veal, both flew over, landed in my field, started up the aeroplane, and while one of them flew my machine home, I was taken back in the rescue ’plane. It was a rather frosty return to Anstey, although I thought that even though I had got myself well and truly lost, I had acted responsibly, had not bent the aeroplane and reported my location to my superiors at base in what I imagined to be good aviation practise.

It was long after the war, somewhere around 1960, that I bumped into Tribe again. It was at Farnborough during one of those annual air shows and I was in the Shell marquee when we suddenly came face to face. We both recognised each other instantly, but his only comment was, ‘You’re still alive then!’

Towards the end of the course we had to take examinations on all aspects of flight and flying, but one thing we were not very happy about was one exam that tested our knowledge of armaments. We were not happy because none of us had ever been given or shown any form of armament training. No lectures, no books to read, absolutely nothing, and it didn’t seem to matter that we hadn’t done anything, an exam on the subject was still to be taken.

Luck was with us, however, for there was an armament instructor at Anstey, an ex-army man, now a flight sergeant armourer, and when we voiced our misgivings to him, he told us not to worry. A couple of days before this particular examination was due, he turned up with what he said was a sample paper on the stuff we might expect to be asked in the exam. So we quickly studied this paper, and then he went through it all with us telling us what the answers to the various questions were.

Forty-eight hours later we all trooped into the examination room, sat down and our exam papers were dished out to us as we sat there with some trepidation. We could not believe our eyes. The exam paper was exactly the same as we had been shown in what he had said was a ‘sample’. So we all passed with flying colours and the flight-sergeant’s reputation as a great instructor was substantially enhanced. He was a real old soldier and did not want any of us to fail.

I continued to add flying hours to my log-book total and reached my 50 without any trouble, finishing up with an ‘Average’ pilot rating. It was now the end of June 1939, and having acquired the knowledge and ability to pilot an aeroplane, I returned home to Battersea, and back to the office, to await information and details of where I would be requested to continue weekend training. I fully expected to be asked to go to Redhill Flying Club which was about the nearest civilian airfield to me that also catered for VR pilots but of course, nothing happened. July came and went, then August, until Sunday 3 September 1939, the same Neville Chamberlain was talking on the radio in the late morning, informing the country that for the second time in 20-odd years Britain and her Empire were once again at war with Germany.

On Friday, 1 September I had received my call-up papers, so I said goodbye to everyone in the office, went home, packed my bags and, having been told to report to the VR centre in Coventry, probably because my records were still in the system at Anstey, started my journey north.

I duly caught the train to Coventry, reported to the centre, where I was asked who I was. Giving my name to the chap at the desk he promptly said he had never heard of me, and to return home! So, having left home in the morning, very much the young lion going off to a fate unknown now that Germany had invaded Poland, I was back home on leave that same night. This was a real anti-climax for me but I have to say it gave much relief to my parents.

The following day, Sunday morning, just after Neville Chamberlain announced that war had been declared, I was out in the street along with everyone else when the first air-raid siren went off. With thoughts of that Raymond Massey film, The Shape of Things to Come, buzzing through my mind, nothing happened and ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Plates

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- Chapter One Just a Lad from London

- Chapter Two 605 Squadron

- Chapter Three The Battle of Britain

- Chapter Four Dangerous Skies

- Chapter Five Instructor

- Chapter Six Off to Australia

- Chapter Seven Darwin

- Chapter Eight Dog-Fights over Darwin

- Chapter Nine Zeros at Six O’clock

- Chapter Ten Back to Europe – and to Normandy

- Chapter Eleven TParis and Peace

- Chapter Twelve Après la Guerre

- Epilogue

- Appendix Record of Service

- Bibliography

- Notes