- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

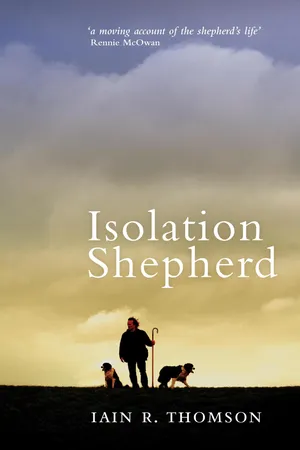

Isolation Shepherd

About this book

In this classic memoir of rural life in the Scottish Highlands, a shepherd chronicles his years in a remote glen before the introduction of electricity.

In August 1956, Iain Thomson and his wife Betty, along with their two-year-old daughter and ten-day-old son, sat huddled in a small boat on Loch Monar in Ross-shire as a storm raged around them. They were bound for a tiny, remote cottage at the western end of the loch which was to be their home for the next four years. Isolation Shepherd is the moving story of those years.

Set against the awesome splendor of some of Scotland's most spectacular scenery, Thomson's classic memoir provides a sensitive, richly detailed account of the shepherd's life through the seasons. In vivid, poetic prose, he recreates the events that shaped his family's life in Glen Strathfarrar before the area was flooded as part of a huge hydro-electric project.

In August 1956, Iain Thomson and his wife Betty, along with their two-year-old daughter and ten-day-old son, sat huddled in a small boat on Loch Monar in Ross-shire as a storm raged around them. They were bound for a tiny, remote cottage at the western end of the loch which was to be their home for the next four years. Isolation Shepherd is the moving story of those years.

Set against the awesome splendor of some of Scotland's most spectacular scenery, Thomson's classic memoir provides a sensitive, richly detailed account of the shepherd's life through the seasons. In vivid, poetic prose, he recreates the events that shaped his family's life in Glen Strathfarrar before the area was flooded as part of a huge hydro-electric project.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

IN WINTER’S GRIP

A portent of winter’s steady approach, is the first faint scatter of snow dressing the high tops of Strathmore during late September. Lying, perhaps for a couple of hours, in the wan morning light there is still enough warmth in the southing sun to clear the peppered flecks by midday. The air feels different; man and beast sense the coming change and react according to age-old instincts. A vague, almost intangible, feeling of unease pervades. The flow of migration heightens apprehension in those who remain. Winter’s threat weighs on mind and action. A need to prepare is felt deep in the very bones of existence.

Sheep must be gathered in early October for their pre-winter waterproofing dip. It is our last visit of the season to the summer pathways of peak and corrie. The changing scene from the lofty ground tells its own story. Grey curtains of rain hang on the horizon. Chill and sweeping, they cut into dull-brown hills pushing the clinging mists of summer heat before them. There is a sense of subduedness for the impending struggle of living through the barren winter is at hand.

One day early in October I reached the narrow sheltered ridge of Bidean with such a feeling within my inner self. Away to the west the view was obscured by low folds of iron cloud driven by the Atlantic winds. Below me, the deer corrie lochan which sparkled only months ago with emerald light was that day, a menacing wave-flecked black surface. I felt an involuntary shudder as I looked down. The cold, damp wind of a changing day blew with plucking fingers at shirt, neck and jacket. Not a day to stand. Mists began to race towards me, precursors of stinging rain which was now driving hard and relentlessly across the Attadale hills. Dropping down a few hundred feet from the crest I came to the bubbling spring which rises clear from a cleft of rock at the head of Coire nam Minn. Of artesian force, its flow remained unchecked in summer or winter – mysterious welling bubbles lipped by green mosses. I paused for a mouthful. Its coldness stung my throat but its sweetness held the elixir of life for those who cared to drink and ask of the ageless hills their secret.

Stepping out to the flat curving plateau of Sgurr a’ Chaorachain, now bleak with its crumbled shattered rocks, I was met by a rolling wall of shivering mist. To be certain of my bearings, I paused to note familiar objects in a world which suddenly changed its dimensions. I stood, the dogs beside me, winds ruffling their coats as they sniffed into the enveloping fog. Suddenly wheeling in, it seemed from nowhere and not ten yards from me, landed a large flock of golden plover. They alighted in unison with such grace of movement. Each bird, as they touched the ground, raised beautifully long, slender wings to arch and meet tip-to-tip over a grey feathered back. Gone was the glossy black breast of courting spring days. Gone the golden back which had glinted in the summer sun. In place was a quiet winter dress, smart and storm-proof, to carry them many weary leagues to some sun-locked strand in Northern Africa. They perched to rest. I stood to watch, conscious of some inner calling. Buffeted by the swirling mists, they shuffled feet to balance in the crude gale’s thrust. Without warning, after some minutes, again with a unity of purpose, they lifted their wings to display the downy white underneath. Then, giving no signal, they took silent flight, instantly to be swallowed by the rain-filled vapours. In a second, however, their enigmatic whistle, an echo from summer ridges, caught my ear. They headed south. I made my way carefully first, for even known rocks become false friends, and then I prodded my way down, anxious to get below the mist and into safe ground. The long-fingered hand of winter was clawing its way into the glen.

Outlying sheep had to be pulled in, often from the grounds of neighbouring estates. Dipped and painted with bright red keel they were easily recognised by their darker colour from the white-coated ewes that had missed these gatherings. The lamb crop was drawn off and along with the cast ewes, or ewes too old to remain another season on the ground, we drove big flocks down to Monar and onto the transport waiting to take them to market. There was a close relationship between sheep prices and shepherds’ wages at that time which is no longer the case when comparing with today’s ratios. In due course I ran about 40 Blackfaced breeding ewes of my own which, allowed as the shepherd’s ‘pack’, were a perquisite of the job. Our own lambs went away with the estate sheep, and marked separately they became the first livestock I ever sold under my own name. Good fresh lambs, they made 84 shillings a head in the Inverness auction mart. My wage at that time totalled eight pounds per week, less the various government deductions. On that same day old Kenny sold three year-old wedders which, being heavy and in good condition, made £6 10s 0d, roughly equalling the shepherd’s weekly wage per head. It took two lambs to make my pay. It now takes approximately five lambs to make up a shepherd’s wage.

These autumn sales saw the culmination of a year’s work and care. With any additional expenses incurred very likely to depress profits below an acceptable level, it became a time of financial worry for many estates. For us it held the delights of a sale’s bustle with the added thrill of seeing stock go through the ring which had been the personal achievement of caring hard work. Days spent away at the sales meant somebody had to stay at home to tend the stock and invariably it was the womenfolk of either household. The two habitations were separated by boat and long paths, so it was a comfort to see that all was well when the first morning smoke drifted from respective chimneys.

After the MacKays retired and the boys left, we were alone for twelve months in Strathmore. Our neighbours were greatly missed in many ways. It is true to say that glen living depended for its practical existence on neighbourliness and the general communal help. Never could one wish for better neighbours than our friends at Pait. I ran Teenie and old Kenny down to Monar with the last of their flitting. Forty years of living in surroundings of complete familiarity is hard to put aside and I saw how keenly the parting was felt as we sailed down that afternoon. Soon we were to feel the difference. I had lambs to sell in Inverness and notice arrived that sheep belonging to Strathmore and the MacKays had been picked up away west at Beinn Dronaig. The letter informed me that the strays lay awaiting collection out at fanks above Attadale. It suited to combine the two jobs.

Betty, children, myself and dogs left Strathmore after dinner on the following day in the Spray and sailed down to Monar. Fortunately not a stormy day, I had persuaded Betty that she could easily manage the boat and the navigating. She looked a little doubtful but after gathering the mails at Monar pier, no objection was made and I watched them sail away west to round the point into the narrows. There was no way of knowing how they would get on. The children waved as the boat vanished from my sight.

Taking Nancy I set off for Inverness with a lift from the ‘postie’ down the pot-holed miles to Struy. For one reason or another I stayed away over two nights and on the third day a plan was made for Sandy, the Fairburn shepherd, to run me round to Attadale by Land Rover. A grand stategy, we would go across to the awaiting sheep and he could then take home to Fairburn any old creatures that might not stand the long drive back to Strathmore.

The day started in fine form considering the previous two nights. Could it have been the fumes of the vehicle? By midday we both succumbed, victims to a distinct and debilitating thirst. By unanimous vote we pulled into the station bar on the platform at Achnashellach. Two trains and several hours were required to quench our affliction. By three o’clock, however it became abundantly clear even to us in the warm sanctity of a convivial hostelry that time and daylight were becoming distinctly limited. We sped off round to Attadale, twice circled the ‘Big House’ to correct our orientation, before, with masterly insight on the original purpose of the day, we chose the long rough pull up to the fanks at Beinn Dronaig. Here we were met by a motley collection of wide-eyed sheep, some of them estate, some of old Kenny’s and one or two my own. Man and beast viewed each other with certain misgivings. With the enthusiasm of crusaders, in not many minutes Sandy and I divided the startled animals according to their category and condition. The old ‘has-beens’ were bundled unceremoniously into the back of the Land Rover and with an unsteady but optimistic wave, in a shower of tyre spurted gravel, Sandy shot away. It was getting late. I looked dubiously out to the fast fading hills and thought of the twelve-mile hike home. Nancy seemed keen and driving about fifty ewes we set off.

The route climbed a faint track high above a steep slope that fell into a dangerous many-waterfalled burn which led into the oppressively narrow pass of Bealach a’ Sgoltaidh. Adding to the gloom, mist began to form with the darkness. We toiled upwards. I now depended on the leading sheep to stay on the track themselves and Nancy to hold any side wanderers. Black cliffs hung with foreboding over the ominous pass, adding evil to the darkness. Mist swirled up from the flats far below, catching a rock, a crevice, a gully here and there, like the touch of white hands clawing with death’s clamminess over grotesque faces. The wind mocked with a hollow laugh amongst bare stones. It grew chilly. I began to think ahead and wonder uneasily for the first time if the boat had reached Strathmore. On into the black chasm, now working by instinct and glad of my ability to see well in the dark, I hurried on. With great relief I felt the track under my feet turn downhill and dimly against the odd star which now broke through the gloom I could see the outline of my own hills of Strathmore.

The sheep, weary and hungry after their imprisonment, became increasingly difficult to handle. My aim had been to reach the stone fank halfway down Strathmore glen, but still some distance from this objective, I peered ahead, my eyes searching the cursed night for a glimpse of the lights of home. From a point I knew the house to be in view, no yellow dot of welcome could be seen. I became prey to increasingly wild conjecture. Finally, with snapping resolve, the sheep were abandoned. I ran, and ran hard, the remaining three or four miles down the rock-strewn stumbling path to the gate of home. Not once did I see a light. My mind jumped alive with horrors. After all, a woman and two small children had been left three days ago to get home by boat without any neighbours to note arrival. No means of communication existed. My fears reached fever pitch before I caught a chink of light from the back room as I ran into the croft and down to the house, breathless and tired, to find all well. The tilley had given bother; a candle stood jauntily in a tin lid on the table beside Betty who sat knitting and wondering if anything had happened to me to explain why I was so overwraught.

Our last visit to neighbour Dolian over in Glen Cannich turned out to be memorable. Again to collect straggler sheep, myself and the boys set out to visit this hardy shepherd’s hideaway, the Nissen-hut bothy of Benula. It lay on the shores of Loch Mullardoch, twelve miles from us by way of Bealach Toll a’ Lochan, the high pass between Sgurr na Lapaich and Riabhachan. We arrived over there late one afternoon to find the shepherd infusing the umpteenth tea of the day. Hard by the hut, to our surprise for the season wore on, was pitched a hiker’s tent. Packed into the bothy, hosted by Dolian and being regaled with tea and a mixture of elaborate stories, were four English hikers. This ex-army hut could not be described as salubrious even amidst the primitiveness of west Benula, nor had any effort been made to redecorate or at least erase the most lurid graffiti which soldiers’ sex-starved imaginations could devise. A perusal of this art form itself took some little time for any who might be so inclined. No matter, Dolian bade us welcome in his grandly magnanimous style and tea in cracked mugs was liberally dispensed. The southern hikers sat ranged open-mouthed on a bench, at once enraptured and engulfed by a brogue-filled flow of west coast humour. In an accent specially tuned for such occasions, the ‘singing shepherd’, as he styled himself, crooned stories which ranged from the corridors of Buckingham Palace to the back of an unseemly pub in Fort William.

The conversation turned to music. In a trice Dolian, from behind a cushion, dragged out an old set of pipes. The narrow tin bothy soon reverberated to March, Strathspey and tramping feet. The MacKays, not to be outdone, took a turn. The English hikers after some ten minutes of this treatment looked visibly shaken and between a change in performers broke in to thank Dolian for all his kindness but indicated they were going to bed. With an imperious nod he blasted them out to ‘Scotland the Brave’. The making of supper, fried venison chops, did not halt the performance for an amateur piper with the reed once between his teeth is hard to stop. Sometime after one o’clock the musical trio, tired of their recital or perhaps out of tunes, retired to various corners. Breakfast was to be early, for some reason which I don’t recall.

Sure enough Dolian came awake before six. However, instead of reaching for the frying pan he, presumably still gripped by some musical infatuation lingering from the recent performance, caught up his pipes. We rose at his opening blast. Soon the smell of the frying pan full of ham and eggs mingled with ‘The 79th’s Farewell to Gibraltar’. The entertainment continued during breakfast and only with reluctance did we leave the bothy about eight o’clock stirred by that splendid tune ‘Leaving Glen Urquhart’. Having forgotten the ensnared English hikers up to that point, our memories were jogged as from an unzipping slit in their tent appeared a pale and haggard face. It blinked. Dolian, at once the cheerful host spoke down, ‘Well, boys, and did yous have a good night?’ The face withdrew without comment. ‘Ach well,’ Dolian turned to us, ‘didn’t I tell them the ground was pretty hard.’

The ‘white shepherd’ became our friend in October. This old shepherding term referred to the line of snow which would settle for the winter at about 1,500 to 2,000 feet. Some mornings, after a night of sleet, we looked out and across to the bold form of Sgurr na Lapaich to see the snow down at its feet. The day would clear with a little sun and the ‘white shepherd’ creep back to his heights, his job done; the straggler sheep being forced down from many an inaccessible rock and lofty corrie, appeared without excuse for having dodged all the summer gatherings. Some proudly had a fine lamb running at heel, long-tailed and lacking any stock mark. Worst of all, if a male lamb, he might be uncastrated and a strong tup lamb left out on the hill unknown to the shepherd could start mating too early in the season. Most ewes were ready for the tup in October and a lamb or stray ram running about could result in the lambing season the following spring being in danger of beginning far too early. The consequent loss might be considerable and this important husbandry feature required special vigilance. Other ewes hunted down by our friend the ‘white shepherd’ often carried their wool clip, and big rolly balls they looked with the new growth pushing up under the old coat. Occasionally sheep came in with two or three season’s fleeces, one on top of the other. The mystery of where these elusive sheep lived, out of sight summer and winter, could never be solved.

By the end of October the breeding flocks had been dipped, worm drenched and clearly keeled with fresh, bright marking fluid. The smell of dip, if they had been through the dipper on a dry day, remained strong on their coats for the rest of the winter. Dipping days held a special terror for the ewes. They played every trick to avoid being put into the pen beside the dipper. Their final desperate act was dumb obstinacy. Nothing for it but brute force and a heavy drag for the shepherd. Care in not breaking off their horns during such heavy handling was essential. If the horn was being used to manhandle a recalcitrant beast then the ear gripped in with the horn helped to take the weight. In spite of precautions, horns broke off, especially in the cross-bred sheep, whose growth was not as strong. A gruesome sight, I hated to see it for you looked down a hole right into the suffering beast’s head. I smartly filled up the gaping orifice with tar.

At the dipper it was a lift and a heave into an opening which projected the panic-stricken animal into freezing water for a full half minute. The brave individuals who had been through the process on too many previous occasions took an almighty leap in an effort to land at the far end of the bath and thus shorten the torture period. The resulting colossal splash rightly infuriated poor Betty. Stationed at the side of the dipper with a forked stick to push each sheep’s head under water she received a faceful of the vile, dirty, stinging dipper wash. The work was best carried out wearing coat and leggings. Steam from trembling sheep and sweating men rose over the sheep-packed pens and out into the thin sunshine of chill October days which often cleared away to frost by the evening. An early start gave the soaking ewes a chance to dry before such a night.

Driven back to the hill after the October dipping, the flocks were left quietly grazing the lower grounds to help them put on a little condition and give heart before the onset of winter. Our rams spent the summer down on the strong lush pastures of the home estate, but about the middle of November a lorry-load of these fat well-holidayed gentlemen arrived at Monar. On rare occasions we spared the tups a walk up the lochside by loading them into one of the boats and sailing them up to their work. However, as this practice made so much mess in the boats we generally opted for the long walk. All the tups would leave Monar pier with great vigour and enthusiasm, but shortly any with excess fat began to show signs of distress. Panting and tongue out, the very heavy boys fell to the back whilst the thin, spry individuals, scenting the ewes, galloped on ahead. It became a difficult drive. Forty tups, half keen as mustard to get ahead, the other half wishing they could go home. Sometimes a really determined ram would just break off and go his own way. Neither dog nor man had any chance to stop him. To make the job easier in latter years I took down a cut of ewes to Monar in the boat, mixed them in with eager tups and then set off up the winding lochside path. The contingent got home in half the time.

To help with the impregnation of the gimmers (young maiden sheep going to the tup for the first time), we made a practice of clipping the wool from their tails. The tups would also have their bellies sheared clear of wool. This latter exercise was as much to facilitate the ram’s movements under snow conditions as to help him in serving the ewes.

In 1956 I put the tups out on 15 November in conditions of singular severity. It started to snow quietly during the afternoon of the previous day. The portents had been ominous, a strange stillness enveloped the glen. Our world seemed to hold its breath. First morning rays had fired the sky an ominous orange-yellow and the daylight began to fail by midday. The tilley, which had to be lit early, shone from the window as I gave the hungry tups a small feed of hay and bruised oats out on the croft under the straggling birch trees. I looked west as the flakes, small at first, puffed down the glen, the sky now of uniform steel-grey shaded the hills to charcoal black. Not a cloud as such was visible. In one vast blanket the heavens looked heavy and solid. For a moment the air on my cheek seemed to warm as a tiny breath of wind hurried on before the first few straying flakes. A storm of unleashed power with all the stealth of a stalking giant seemed to be creeping in on us. On the flats not a hoof was to be seen, the deer must have climbed out to sheltered haunts earlier in the day. A lone hoodie crow silently skudded down before the now-freshening wind, doubtless making for the pines of Reidh Cruaidh.

I busied myself about the byre getting in the cattle early, putting hay into the hakes up above their heads, dry rashes and bracken under their feet for bedding. The first rattle of the corrugated iron sheets at the corner of the byre told of wind to come and the blast was not long delayed. I noted the barometer had fallen near to the 28° mark as I went in for an afternoon mouthful of tea. The tups, having finished their bite of hay, stood in a tight group behind a low line of dyke which ran out from the kitchen garden. I went out for a last look round. The glen had vanished before an advancing white wall. The wind, now blowing hard, snatched at the last of the yellowed birch leaves and caught the white strands of dying grass on the bare croft, threshing them against the dyke side. At last, almost in relief, came the snow, blasting, stinging with an eye-screwing ferocity. The world shrank to only a few paces wide and was suddenly dense with choking particles which filled the mouth and cut the breath. In an instant cheeks and ears lost feeling, the hair on my head became coated, caked and heavy. A turn of the head snatched the breath away. A savage blizzard, the most dangerous of all weather conditions, held us in its merciless grip. I made for the house. Betty was making up the fire, stacked peats lay to one side of the range, cu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Isolation Shepherd (poem)

- Map of Loch Monar and District

- By Storm to Strathmore

- The Great Strath

- Shepherding Ways

- Remoteness Living

- Filling the Salt Barrel

- The Lambing Round

- On the Loch

- A Night Sail

- Droving Home

- The Pait Blend

- The Last Stalk

- In Winter’s Grip

- The Christmas Pipe

- Epilogue

- Burning Yesterday (poem)

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Isolation Shepherd by Iain Thomson,Iain R. Thomson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.