- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A look at Scotland before it was Scotland, with illustrations and photos included: "An outstanding book." —

Current Archaeology

Early historic Scotland—from the fifth to the tenth century AD—was home to a variety of diverse peoples and cultures, all competing for land and supremacy. Yet by the eleventh century it had become a single, unified kingdom, known as Alba, under a stable and successful monarchy. How did this happen, and when?

At the heart of this mystery lies the extraordinary influence of the Picts and of their neighbors, the Gaels—originally immigrants from Ireland. In this new and revised edition of her acclaimed book, Sally M. Foster establishes the nature of their contribution and, drawing on the latest archaeological evidence and research, highlights numerous themes, including the following: the origins of the Picts and Gaels; the significance of the remarkable Pictish symbols and other early historic sculpture; the art of war and the role of kingship in tribal society; settlement, agriculture, industry and trade; religious beliefs and the impact of Christianity; and how the Picts and Gaels became Scots.

Early historic Scotland—from the fifth to the tenth century AD—was home to a variety of diverse peoples and cultures, all competing for land and supremacy. Yet by the eleventh century it had become a single, unified kingdom, known as Alba, under a stable and successful monarchy. How did this happen, and when?

At the heart of this mystery lies the extraordinary influence of the Picts and of their neighbors, the Gaels—originally immigrants from Ireland. In this new and revised edition of her acclaimed book, Sally M. Foster establishes the nature of their contribution and, drawing on the latest archaeological evidence and research, highlights numerous themes, including the following: the origins of the Picts and Gaels; the significance of the remarkable Pictish symbols and other early historic sculpture; the art of war and the role of kingship in tribal society; settlement, agriculture, industry and trade; religious beliefs and the impact of Christianity; and how the Picts and Gaels became Scots.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Setting the scene

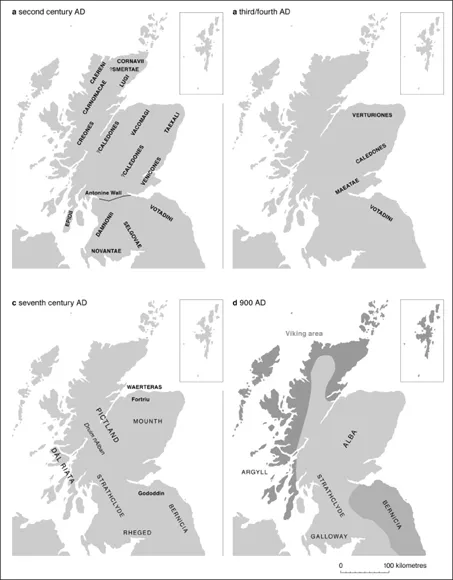

Early historic Scotland, from the 5th to 10th centuries, was home to five different peoples and cultures: the Picts, Dál Riata (Gaels), Britons, Angles and latterly the Vikings. By the early 11th century the first four of these groups were unified and Scotland had established a stable and successful monarchy. Geographically it extended south into modern England, while its western and northern fringes, including Caithness, were Norwegian. Since the 10th century, historians have tended to credit one man with laying the foundations of this modern Scottish nation, Cinaed mac Ailpín (Kenneth son of Alpin), a Gael who in 842/3 rose to prominence as ruler of the Picts. Today historians have a different view of Cinaed’s role. On the one hand, the earlier achievements of the Picts in beginning the process of consolidation of the Scottish kingdom is recognised; on the other hand, the events of c.900 are identified as the more important political landmark than the beginning of Cinaed’s reign. At this point the name Alba, which had originally been the Gaelic word for Great Britain as a whole, was appropriated for Pictland by a new Scottish nation consciously attempting to break with the past. It did so by defining a new type of kingdom, which could be expressed in terms of a territory as well as a group of people.

The key questions are therefore: when did this process of consolidation take place, and why, how and where? There are no ready answers to any of these questions, but as we review the various strands of evidence for the Picts and Dál Riata a clearer picture will begin to emerge.

Who were the Picts?

Classical and later early historic sources use a variety of evolving terms to signify the people who inhabited the area of modern Scotland and/or their territorial divisions prior to the late 8th century (7). Of these terms Picti, first recorded in 297 and possibly a Roman derisory nickname meaning ‘the painted ones’, has been the most enduring. Then, as in later Classical sources, the Picts were referred to as assailants of the Roman frontier in Britain (8). Much ink has been spilt over exactly who the ancient writers meant by Picts, but it seems to be a generic term for threatening peoples living north of the Forth–Clyde isthmus who lacked romanitas; unlike the people in southern Britain and within the empire, these were barbarians. The Alexandrian geographer Ptolemy, writing c. 140–150, recorded as many as twelve tribes inhabiting the region. His sources included information gathered by Agricola, whose son-in-law Tacitus, the Roman historian, documented how in 83 at the battle of Mons Graupius (precise location unknown) some of these tribes combined against the army of his father-in-law. We do not know how individuals identified themselves with such tribes. They may have only been loose confederations of people with limited potential for corporate activity, yet they apparently had meeting places, were able to muster military forces when required, had widespread contacts and were capable of participating in long-distance relationships.

7. The known names of peoples and kingdoms in Scotland between the 1st century and the beginning of the 10th century. Precise locations are often difficult to define and we cannot be certain that the various sources named all the existing peoples or completely understood what they were describing.

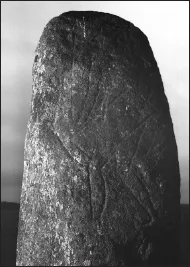

8. The Collessie Stone, Fife: an early native depiction of a Pict.

The appearance of the term Picti cannot be used to infer that the Picts were a ‘nation’ or uniform people prior to the end of the 3rd century, nor that the people to whom this term was applied had suddenly changed in any way. On the contrary, the Romans were simply distinguishing the inhabitants of Britain who had changed by becoming Romanised (Britones) from those to the north who had not. In the Classical sources at least two main internal divisions among this un-Romanised population are referred to: the Maeatae and Caledones of the late 2nd/early 3rd century, and, by the mid 4th century, the Verturiones and Dicalydones. If we follow James Fraser (2009), the political birth of the Picts as a single people ruled by a single king does not take place until the late 7th century, a result of the conscious and determined extension and consolidation of royal authority (see p. 37). It was around 700 that a Pictish scholar apparently chose to reinforce the idea of the Picts as a people with stigmata (marks on their skin) when he invented the story that the Picts sailed from Scythia, where Classical Antique sources also describe painted people. The creation of this origin legend was part of the conscious process of building a transformed Pictish identity and solidarity at a time of political change (Fraser 2011). It suited the people of north-eastern Scotland to adopt the Roman term for them. We cannot be sure that these were the sole inhabitants of the country but we can be confident that all these people were simply the descendants of the native Iron Age tribes of Scotland, most of whom were never part of the Roman Empire, or were only directly affected by it for short periods of time. The notion of the Picts having existed in Galloway is now recognised as a myth that arose out of a misunderstanding by medieval writers; this area was occupied by other tribes (see ‘Who were their neighbours?’, page 5).

Who were the Dál Riata?

The Dál Riata were Gaels who had connections with the Antrim tribe of the Dál Riata in north-east Ireland (Plate 3). Obscure origin legend first documented in the 10th century has it that c. 500 one of their number, Fergus Mór mac Eirc, established a new kingdom in Argyll in response to rival dynastic pressures in Ireland. For many years this ‘event’ has been used to explain why Argyll became Gaelic speaking. However, as David Dumville (2002) baldly puts it, ‘stories of Dalriadic origins cannot be held to be worthy of acceptance as history’, and Ewan Campbell (2001) has emphasised that there is no archaeological evidence for any such migration at this time. The distribution of prehistoric artefacts and similarities in certain monument types attest, rather, to a much longer tradition of contact between north-east Ireland and west Scotland, beginning in Neolithic times, and Campbell argues that Gaelic became the main language in Scotland west of Druim nAlban sometime during the 1st millennium BC, the short sea-crossing of the North Channel linking rather than dividing those who lived on either side. Taking into account the later date of the sources, historians therefore need to seek other explanations for the creation of the Fergus Mór mac Eirc foundation legend. A second and probably older origin legend, reported by Bede in the 8th century, attributes the meaning of Dál Riata (tribe/division of Riata) to a leader, Reuda, who came from Ireland. The evidence for Gaelic speakers in south Scotland, Wales, Cornwall and Devon around the mid 1st millennium should also be noted.

In most modern literature the Dál Riata are referred to as Scots. This is a direct translation of Scot(t)i (perhaps meaning ‘pirates’) first used by the Classical sources to distinguish them from Picti, both of whom are described as early allies in assaults against the Roman Empire in Britain. From the mid 4th century Britain was being ‘harassed in a never-ending series of disasters’ by the Picts, Scoti, Saxons and Attacotti (an unidentified belligerent tribe from either Ireland or the Western Isles). This was part of a pan-European phenomenon of attacks against the empire that culminated, in some areas, in new settlements, such as the Anglo-Saxon takeover of southern and eastern Britain.

But, in fact, when Classical authors and later early historic sources used the term Scoti it had a completely different meaning to its modern English usage. It was used to mean all Gaelic speakers in Britain and Ireland – people who referred to themselves as Goídil (Gaels) (we must remember the importance of language at this time in defining identity). Only after political changes c.900 is it appropriate to begin to use the term ‘Scots’ in its more modern sense (see chapter 7). The names used in this book are therefore slightly at variance to what most readers may be familiar with but they reflect the political circumstances more clearly.

Who were their neighbours?

The Picts and Dál Riata had a number of contemporary neighbours whose interrelated history was instrumental to their mutual development and will be discussed where directly relevant. To the south of the Forth–Clyde isthmus the Romans were familiar with a number of native British tribes: the Votadini, Selgovae, Novantae and Damnonii (see 7a). These were the people who by the 6th century had evolved into the British kingdoms of Gododdin in the Lothian area (the name Gododdin comes from the Votadini, whose principal stronghold was Din Eidyn, probably Castle Rock, Edinburgh), Strathclyde (based on Dumbarton Rock) and others in south-west Scotland and north-west England (see 7c). But the Angles – Germanic peoples who first migrated to eastern Britain in the early 5th century – were soon to make their presence felt in the north. Around the mid 6th century they had established the kingdom of Bernicia in Northumbria with its stronghold at Bamburgh, and from 638, with the capture of Edinburgh, they also gained Lothian (until 973) and, more briefly, territory to the north of the Forth.

Initially hostile to Dál Riata, Picts, Angles and Britons alike were the Vikings, aggressive invaders from Scandinavia (largely Norway, but latterly Denmark) whose first recorded attack on Britain and Ireland took place in 793 on Lindisfarne in Bernicia. From the following year their attacks increased and were reported by contemporary annals as amounting to ‘devastation of all the islands of Britain by the gentiles [pagans]’. Shortly afterwards settlers also came. They colonised the northern and western fringes of Scotland, including large parts of both Pictland and Argyll, as well as establishing important bases around the Irish Sea (9). By the later 9th century Norse settlement was firmly established in the Northern Isles and Caithness. Ultimately it was the presence of the Vikings and their continuing expansionist tendencies that were instrumental in the final unification of the Dál Riata and Picts (see 7d).

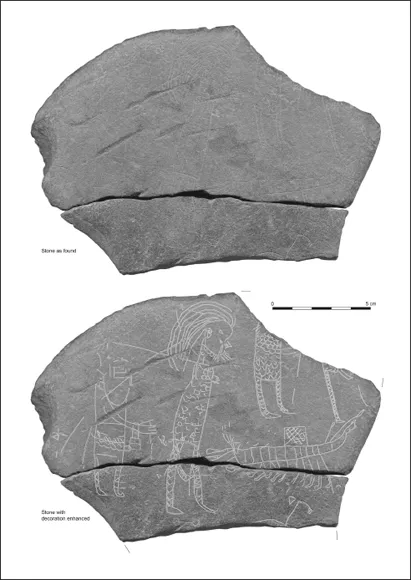

9. One possible interpretation of this incised slate from the excavated Gaelic monastery on Inchmarnock (decoration here enhanced) is that it depicts a Viking raider leading a captive youth or monk, carrying a bag or holy relic, to his boat.

The history of interest in the Picts and Dál Riata

As first noted by John Toland in 1726, ‘they are apt all over Scotland to make everything Pictish, whose origin they do not know’ (quoted in Cowan 2000): ‘Pictish towers’, brochs built by the inhabitants of north and west Scotland from whom the historical Picts were descended, are the classic example. As Cowan has shown, this interest is part of the long, ongoing process of invention of a ‘Celtic Scotland’ that today we seek to place on a more academically robust, if less romantic, footing. The Picts primarily captured the imagination of early antiquaries and travellers because of their unique symbols and other distinguishing characteristics. This bias in interest continues although it is gradually being redressed.

Antiquarians of the 16th century, such as William Camden and Hector Boece, were interested in the Picts, though their comments are primarily restricted to observations derived from Classical texts. By the 18th century travellers such as Thomas Pennant and the compilers of The Statistical Account of Scotland (1791–97) were drawing attention to the existence of surviving physical remains, particularly sculpted stones (10), and monuments were being accurately mapped for the first time (11). It was these carvings that received most attention during the 19th century and first half of the 20th; a concern for their deteriorating condition led to the publication in 1903 of the first, and to date only, published catalogue of the corpus of Scottish sculpture (Allen and Anderson’s Early Christian Monuments of Scotland). The mid 19th century also witnessed the foundations of serious research into the early historic documentary sources.

But it is only since the 1950s that early historic studies in Scotland fully came into their own, with leaps in our knowledge through excavation, field survey and historical, place-name and art-historical research, enhanced by interpretative analyses of this evidence from a variety of differing perspectives. A major landmark was the Dundee conference in 1952 that resulted in the first comprehensive survey of Pictish archaeology, The Problem of the Picts (Wainwright [ed.] 1955). The memorable title of this book has unfortunately been something of a hindrance to later studies, since it reinforces the ‘enigmatic’ aspects of the Picts; despite the disclosures of modern research, it is sometimes still difficult to shatter this perception.

But to be fair to its contributors, in 1952 they could not ‘point to a single fortress or to a single dwelling or burial and say with certainty that it is Pictish… The problem lies in the recognition or identification of material as Pictish.’ This dilemma is perhaps echoed in Isabel Henderson’s The Picts (1967): ‘quite the darkest of the peoples of Dark Age Britain’. This first modern survey was inevitably biased towards historical and art-historical aspects but is reflective of a time when careful scholarship was beginning to dash fantasies about the Picts.

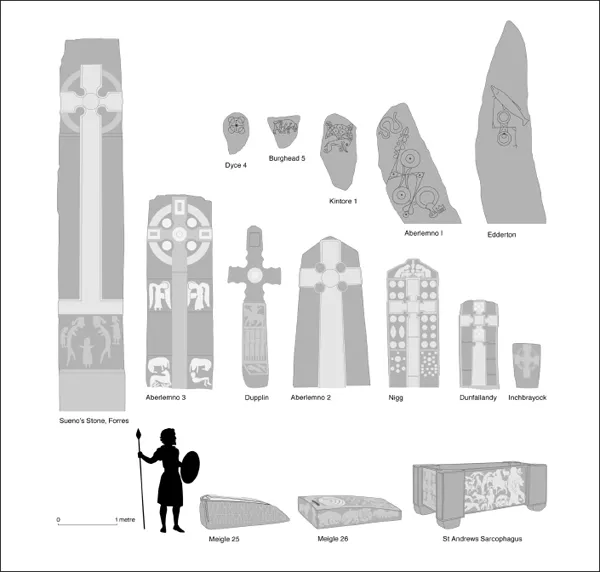

10. Examples illustrative of the range of Pictish sculptures.

Significant advances in the recognition of archaeological sites as Pictish or early ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Dedication page

- List of plates and figures

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introductory note

- 1 Setting the scene

- 2 Communicating with the past: The sources

- 3 The residence of power

- 4 Agriculture, industry and trade: The currency of authority

- 5 The strength of belief

- 6 From ‘wandering thieves’ to lords of war

- 7 Alba: The emergence of the Scottish nation

- Monuments and museums to visit

- Glossary

- Further reading

- Index

- Plate Section

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Picts, Gaels and Scots by Sally M. Foster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.