![]()

Zen Today

Daisetsu Suzuki

Dogen aspired sincerely to follow Buddha. This aspiration producing noble deeds was his Zen. Today Dogen’s Zen has a larger number of followers in Japan than any other sect of Buddhism. They are trying to be one with their daily vocation, thus living their Zen.

Before Zen came to Japan, Chinese Zen derived from Bodhidharma had five schools and seven sects. Of those Soto which Dogen brought to Japan and Rinzai which Daisetsu Suzuki, 1872–1966 has upheld, have flourished in Japan. Suzuki is a profound scholar as well as a Zen master. His view is easily understood through many books he has written in English. But for those who have not had chance to study his thought a careful exposition on his Zen will be needed. Rinzai, Lin-chi, died in 867, was a Chinese Zen master, who used Koan frequently. Koan is the study of profound, bizarre, incomprehensible questions on Zen at its most esoteric. Zen is a belief in the nexus of numberless interrelationships, in history and the world. So what sounds like a far-fetched question is to serve as the key to some hitherto-unconnected ideas. A polo game which took place yesterday is supposed to have a vital connection with the pillar of the discussion-hall where Koan is being studied now. However far-fetched two things may seem to common sense, they are always two integral parts of the totality of which the people who are taking part in the Koan are members. The view of this totality brings about fuller disclosure of the true self, hitherto concealed in the self. Koan is the means by which the given self is enlightened into the ideal self of compassion and coherence. The thought of death and life eternal no more troubles the ideal self.

Suzuki has been blessed with a number of things which the average man cannot hope to enjoy: brilliance, longevity, chance to see all the world firsthand. He is in a good position to look at East and West, Old and New, thus evaluating Zen from a high angle. He has lived in a Zen temple, studied and taught at some of the best universities of the world today, written more than one hundred books which have been moving many people who read English and Japanese. He is over 90 years old. But he is creative and active. He travels like a cloud and writes like Paul.

His Zen is a great synthesis. Buddha’s view, Chinese Zen like that of Rinzai or Lin-chi, Taoism, Confucianism, Shinto have been synthesized into one vast stand. And it is interpreted in relation to western thought and Christianity. We are going to listen to him as he gives a definition of Zen.

Zen is able to lose itself in order to reveal its true value. Japanese culture at its best is the result of Zen in action. The study of Chinese thought flourished because of the encouragement given by Zen. The art of tea has become spiritually ennobling because of its affiliation with Zen. Literature like haiku and waka has gained a distinct note of virility through the incorporation of Zen into it. Japanese chivalry has become nobler under the influence of Zen. The Japanese love of Nature has become more genuine and intimate due to the Zen view of the presence in Nature of Original Abode from which we all come and to which we shall return ultimately. Painting and sketches like sumie have gained vigor, solace and charm since the masculine spirit of Zen flickers in and through them. Men of action have become charged with the quality of being direct, dynamic, durable: this is due to the work of Zen too.

In short Zen is functioning wherever there is simplicity, directness, creativity. It goes beyond verbalism of any kind. The limitations of human language are keenly felt when it comes to give expression to the most fascinating nucleus of human experience. Suffice it to state that Zen is the most immediate grasp of man and his life, in this mysterious and yet marvellous world. Zen is different from philosophy. The latter uses concepts with which to describe life. Zen reminds you of experience at its noblest and best. There Zen is already vividly present. All that is unforgettable, revealing, exciting is Zen.

How wondrous this, how mysterious!

I carry fuel, I draw water.

Buddha was pragmatic in doing the work of salvation to people of all conditions in India for 45 years. Zen is the truth of life as he saw it. Life of consistent altruism is the way out of the misery of the world. Doing the deed of overwhelming kindness saves the doer from his obsession with foibles of human nature. Buddha lived and strove in Original Buddhism, working wonders everywhere in India until A’soka (268–232 B.C., on the throne) made the whole continent of India a Buddhist kingdom.

Buddhism later became impotent in India because it grew theologically cumbersome. As Suzuki points out, Chinese thought has added its practicality to Indian Buddhism as the latter was introduced into China. Fuel carrying, road mending, tea making, and some other values of economics have come to be labeled Zen under the Chinese Zen masters—like Eno, Hui-neng, who died in 713. The bizarre, incomprehensible questions and answers recorded in the annals of Chinese Zen means among other things this. They are to urge men to action. The mystery of life is inexhaustible. Never mind quibbling over it, thus wasting precious time. Stop worrying about it. Do what is most urgently needed. This is the message of Mondo, the brisk interchange of those strange words between the master and pupil.

Mondo or Koan is also to remind us of the togetherness of things, which is often missed by victims of hatred or provincialism. The nexus of infinite interrelationships characterizes the world of men and things. An answer which is surprising, far-fetched, bizarre must be regarded as the key to this nexus. The cause-effect nexus of history is often beyond the imagination of short-sighted men. Zen begins with the conviction that between Buddha’s insight into life and the misery of men in this nuclear age there is a vital connection. Between the pride of statesmen in many nations and the possibility of the destruction of the world there is a connection. Between the indifference of the world to infinite compassion and the melancholy of many moderns there is a connection. Between the superhuman vitality with which Suzuki is working indefatigably, writing, lecturing, traveling and the availability of the love of Heavenly Reason which Suzuki has been stressing as the source of all good work on the part of a Zen master, there must be some definite interrelatedness.

As to the ultimate reality from which we all come and to which we shall return sooner or later Suzuki uses many words. The Abode of Great Origin, Final Reality, Original Abode, Tao, Dharma, God, The Primary Mind, The Unknown, The Unconscious, The True, The Limit of Reality (Bhutakoti), the Void (sunyata), suchness or thusness (tathata).

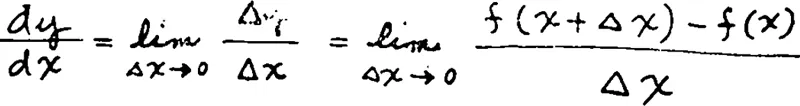

Here is the attempt to see in synopsis all the Deities of Indian Thought, Chinese Thought, Christianity, Western Thought, Japanese Thought. Suzuki sees the coherent togetherness of these Deities, incorporated into one vast experience of Zen. These Deities are so many functions of God whose will is infinite love. Zen feels at home in any tradition which a man may happen to represent, whether it be Indian, Chinese, Christian, Occidentally Philosophical. Suzuki sees a rapprochement between Zen and any tradition or point of view. To a mathematically-minded reader the word koti, part of Bhutakoti, or kotis of gods must be interesting, Koti means limit. When Reality comes to its limit it is divine. All the above deities are one when they converge to their limit. Modern mathematics has made progress because of its use of the concepts, limit, convergence, infinity. Limit operations including clever ideas of convergence form a special chapter. Calculus is possible because of taking a limit as in differentiation.

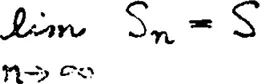

Here the quotient has a limit when Δx approaches zero. Integration is the inverse of differentiation. There is a vital connection between the two. When we come to deal with infinite series it is important for us to see whether or not those series converge. If a series (Sn) has a limit S to which it approaches such that the following property holds, then this series is said to converge:

Infinity is bound to be involved as motion is taken seriously. Modern mathematics is a science of infinity which is the most important idea on which it hinges.

Suzuki mentions limit, infinity, in connection with the view of reality, thus hinting at a connection between Zen and mathematics. This is natural because Zen must continue to seek all connections among values and meanings of civilization. Suzuki’s implication is that all the historically envisaged ideas of God must be connected with one another for those who are able to see through the forbidding differences of the concepts which stand for many functions of God whose convergence to one another is possible as a limit. God’s resourcefulness is here implied.

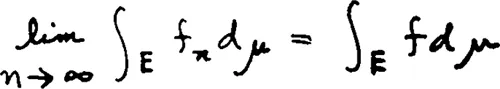

The Lebesgue theory marks a striking advance in modern mathematics. Its advantage over the Riemann integral is its invention of new ideas of convergence such as Lebesgue’s Monotone Convergence and Dominated Convergence. Through these new ideas the calculus has been refined, enriched, expanded.

Likewise religion may be enriched, expanded, refined through the idea of koti, limit, in the sense that all the historical views of God converge to one another, when these views are seen from new angles. This is akin to what the historian Arnold Toynbee stresses in his Gifford Lectures, An Historian’s Approach to Religion, Oxford University Press, 1956, P. 299. We cannot harden our hearts against a view slightly different from ours without hardening them against the God of Christ. We must not let our narrowness reflect on the idea of God such that He is either a monster or mystery.

Zen discloses a new connection. Wherever a hitherto-concealed value swims into our ken, there Zen is at work. A Japanese No Play called Yama-Uba is a case in point. “The old woman of the mountain” is the meaning of this title. She looks tired, having suffered for others who suffered. She has rough hands, having worked hard for all those who needed her help. Her face is wrinkled. Her hair is white. Her life has been a series of pains, which she has gladly suffered for others. She travels from one end of the world to another, having no rest, no recreation, no remuneration. This is unfair. But the old lady of the mountain is more than human. Another name for her is the Dharma Compassion, counteracting all unfairness in the world of men. The Dharma Compassion is infinitely resourceful, disclosing itself in an indeterminate number of beneficent forms, thus helping men in agony everywhere.

Each new age, each new situation, each new problem may be unexpectedly terrible. But Zen men are not in despair. They believe in the coming of a new Yama-Uba to cope with the new situation. Forever to transmigrate is her destiny. Forever from mountain to mountain, from trouble to trouble, from mortification to mortification, from terror to terror, moving, saving, healing, she travels on.

This is a new dimension of religion which we should realize. Mercy is not always lovely, charming, youthful, as the West has tended to depict the savior, Christ, Virgin Mary. In ugliness, black terror, disease, despair is God at work too. Suzuki’s reference to the Japanese No Play may be attention-compelling to some reader.

Behold she was here a while ago,

Now she is no more to be seen anywhere;

She flies over the mountains,—

Suzuki sees Zen even in swordplay. This may displease some reader who is praying for peace. But if we take a sympathetic attitude toward it, it begins to give a helpful suggestion. There is some one of some race we can not love genuinely. Enmity is a feeling which is in practically every person. But Zen is not Zen if this enmity is not transmuted into compassion. The will to victory must vanish so that it may be changed into the will to suffering, vital and vicarious. This change is brought about by the Dharma of Cosmic Compassion when the hostile self surrenders itself to it.

“The defeated weep in agony.”

This is what Buddha realized keenly as he dealt with friends of his and studied the history of his people. The ethic of sharing agony with those who are agonized is the ethic of Zen. Seeing this, Suzuki explains swordsmanship from a new angle, saying that the only true victor in swordplay is he who transcends any enmity swirling in his own mind. It consists not in defeating the opponent but in not being defeated. Here he tells a story of a certain swordsman named Tsukahara Bokuden who regarded the sword not as a weapon of murder but as an instrument of spiritual discipline. When Bokuden was crossing Lake Biwa in a rowboat with many other passengers, a rough samurai challenged him to have a fight. So they decided to have a duel on an isle so that the other passengers might not be troubled. As soon as the boat was near enough, the challenger jumped off the boat. Bokuden took off his own swords, handing them to the boatman. To all appearances he was about to follow the samurai onto the isle, when the former suddenly took the oar away from the boatman. Pushing it against the land, he gave a back drive to the boat. So the boat made a sudden departure from the isle, plunging into the deeper water safely away from the samurai, ready to fight on the deserted isle. Bokuden’s art was a quick wit to avoid a deadly duel. This is possible only on the part of someone who is calm at the most fatal moment because of the boundless compassion with which to include even the opponent.

There is a connection between Zen which is deep thought of life in relation to death and swordsmanship which may have to encounter death any time. In both of them the way to life is benign inclusion of the opponent who may be either within us or outside of us. The narrow selfishness bothering us from within and the enemy eager to kill us with his sword are both fatally dreadful as long as we are alienated from the Cosmic Support who is infinite compassion. This general instruction of coping with death is made more concrete by a few detailed prescriptions for us to follow.

First, a rat may become terribly unmanageable when he is cornered into a desperate situation. Even the best rat-catching cat may fail in a combat with a rat in a hopeless predicament. Interpreted into a contemporary scene even a small nation like Korea or Cuba may put up a formidable resistance against a strong nation when the former is cornered into a hopelessly difficult situation. If the smaller nation has nuclear weapons she may destroy the larger nation when the former begins her offensive soon enough.

Second, Suzuki’s reference to no-mindedness has this suggestion to make. It teaches us to be free from our obsession with thought of our enemy. Our enemy may not be trying to cause us trouble all the time. He may be thinking of something totally different from the tension between him and us. We imagine his enmity to be more than it actually is. He may be deeply worried about the precarious situation in which he finds himself. He may be troubled by the inevitable coming of catastrophes, accidents, death itself. He may be too busy with his own work of trying to make his own position in society secure. Perhaps he has more vulnerable spots in himself ...