- 457 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

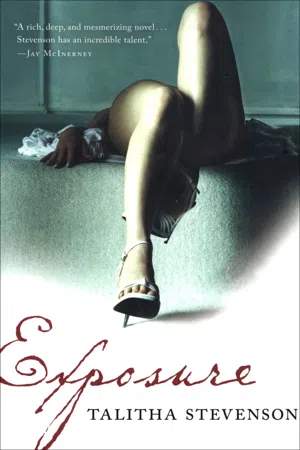

Exposure

About this book

"Rich and psychologically astute . . . refracts the life of an upper-middle-class English family . . . through the prism of a single, scandalous affair." —

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

Prominent lawyer Alistair Langford has worked hard to achieve his immense ambitions, but in the course of just one evening he recklessly destroys everything. The scandal threatens his marriage and exposes a secret he has hidden his entire adult life.

Meanwhile, his son Luke, who has led a privileged life but also has worked hard to achieve his own success, has fallen in love with a beautiful actress. When she suddenly leaves him, he plummets into a dangerous depression. His ideals in tatters, he seeks a kind of redemption by taking in two asylum seekers from Kosovo, whose struggles contrast starkly and poignantly with his own.

A deftly plotted, highly suspenseful, and astutely observed morality tale, Exposure explores the dangerous pleasure of offering charity, the effects of deceit and shame on a rigidly complacent family, and the nature of love among family and friends.

"A rich, deep and mesmerizing novel that simultaneously projects a sense of casual grace and of inexorability." —Jay McInerney

"An unapologetic love story, reminding us first of our fragility and then of the ability to forgive." — Entertainment Weekly

"Class consciousness, sexual obsession, and familial issues make for queasy yet engaging bedfellows in Exposure . . . Stevenson writes with a careful grace, and an emotional honesty that is wise well beyond her 28 years." — New York Post

"[ Exposure] confirms the young English author's uncanny flair for psychological plots." — Vogue

Prominent lawyer Alistair Langford has worked hard to achieve his immense ambitions, but in the course of just one evening he recklessly destroys everything. The scandal threatens his marriage and exposes a secret he has hidden his entire adult life.

Meanwhile, his son Luke, who has led a privileged life but also has worked hard to achieve his own success, has fallen in love with a beautiful actress. When she suddenly leaves him, he plummets into a dangerous depression. His ideals in tatters, he seeks a kind of redemption by taking in two asylum seekers from Kosovo, whose struggles contrast starkly and poignantly with his own.

A deftly plotted, highly suspenseful, and astutely observed morality tale, Exposure explores the dangerous pleasure of offering charity, the effects of deceit and shame on a rigidly complacent family, and the nature of love among family and friends.

"A rich, deep and mesmerizing novel that simultaneously projects a sense of casual grace and of inexorability." —Jay McInerney

"An unapologetic love story, reminding us first of our fragility and then of the ability to forgive." — Entertainment Weekly

"Class consciousness, sexual obsession, and familial issues make for queasy yet engaging bedfellows in Exposure . . . Stevenson writes with a careful grace, and an emotional honesty that is wise well beyond her 28 years." — New York Post

"[ Exposure] confirms the young English author's uncanny flair for psychological plots." — Vogue

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

As if someone had come into the room and caused him to lose the thread of what he was saying, Alistair Langford had forgotten what he believed in. He had spent his life making ruthless compromises for the sake of his ideals and it had been a great surprise to find that they had just drifted off. The rest of humanity had continued to drive cars and carry babies and have lunch just the same. He gave the sky a wry smile because it was his sixty-third birthday and he had never expected to spend it standing on the edge of a cliff.

Sea spray blew up and fine chalk dust puffed over the drop as if in reply. He was not usually one for superfluous journeys, not one to leave the table for an ordinary sunset or moon. But now he looked down quietly at the grey sea, and the waves that rose and formed and broke in on themselves.

Nothing frightening had ever happened to him before. He had kept clear of all danger. He had cultivated interests rather than passions and had always presented his eyes with elegance rather than troublesome beauty. It was a discreet pleasure that he took in his nineteenth-century tables, his John Cafe candlesticks, his Chippendale chairs. These were all arrangements of lines and angles, essentially, prey to the laws of trigonometry.

The sea was very different. He looked at his shoes on the rough yellow grass. Behind him, two colourful girls came along the path. They were talking a language he couldn’t understand and they laughed as they passed. For a moment, Alistair was afraid they were mocking his walking-stick, but he let the thought go with the sound of their voices and their shoes thudding on the soft chalk. What on earth was the point of worrying about his dignity now? Besides, it was too hot.

Beneath him the sea looked cold and fierce and he liked watching it hitting the bottom of the cliffs and spraying up in arcs against the chalk.

His leg had only been mobile for a week now and he knew the physiotherapist would not have encouraged him to drive or to walk this far. He was genuinely amazed at the way he had just grabbed the car keys and left. Why? He knew what had happened—he had been struck by a strong physical memory: the sensation of space, of the whole Channel in front of you. It had taken hold of his stomach like hunger. Next thing he knew he had walked out of his mother’s old house—leaving his son packing up her holy china and brass relics, her lifetime’s treasures—and made his way up here.

It was a warm wind and unusually hot even for August. As he drove through Dover, he had found it composed of white-hot, abandoned streets. There was a sense of what the hours after a nuclear disaster might be like in the dry, bleached lawns, the shrivelled geraniums swinging eerily in their baskets on Maison Dieu Road.

He had wound his way up the cliff road, left the car in the public car park and limped along the path in search of the view. And now here it was: the Channel, grey-green and empty all the way to Calais. A disembodied female voice drifted in from the vast ferry terminal on the right. It urged people in toneless French and German to get on or get off the boat. It all seemed rather poindess—but ultimately benign. There were seagull cries, which were always faintly exciting.

It was strange how this view still found its way into his dreams. As a boy, he had often spent whole afternoons hiding and plotting up here, but today he was exhausted after just ten minutes or so. He thudded his walking-stick against the ground, feeling obscurely disappointed. Still, he told himself, there was always the danger that excessive solitude might start him reliving the event. He was at least avoiding that.

In fact, there was no reason to be concerned about this, because his mind was clean of the recent past. Bizarre as it was, he was not haunted by the event at all, but by something his wife had said about it. At the hospital, holding his hand, Rosalind had turned her white face on him and said, ‘But how could you not have heard them, Alistair? How? They must have been . . . silent as dogs!

The sinister image was so foreign, so film-noir sophisticated somehow on her neat, scrubbed mouth. It had made him feel oddly threatened. It was as if she had been hiding some part of herself from him all these years. Suddenly it occurred to him that she might have had an affair. She might have been duplicitous.

How could you tell with other people, even your wife? Was he sixty-three and still unable to feel certain of any of his instincts?

No, surely not. And it was ridiculous, the idea of Rosalind having an affair. In the complacent past he had almost wished she would, because sometimes he wanted her stripped of that inhuman faultlessness for which he had fallen in love with her. Now the idea felt dangerous, though. He needed her elegant conformity more than he ever had, as much as frightened children need stories at night. One act of violence had sent cracks through everything he touched.

Why had she used that odd phrase?

In fact, even though she had not actually been there at the time, it was a good description. The two men had been silent as dogs, padding under the street-lamps after him in their soft trainers. And when they stopped they were invisible too, except for a star of light that bounced off the buckle of the smaller one’s belt. He noticed it and moved back a little, behind the phone box—and the star went out.

At exactly that moment, the front door opened four houses along, spilling light voluptuously down the white steps and through the shiny black railings. Bars of shadow grew over the London pavement. Piano music and that singing kind of laughter, which is not really laughter but civilized conspiracy, drifted out with a faint scent of cigar smoke. The host had his arm round the hostess and she raised her hand to hold it, her bracelet or watch-face playing the light back obliviously at the belt buckle. The host said: ‘Well, you’ll send Roz our love, won’t you?’

‘Yes, of course I will,’ Alistair said.

The smaller man glanced at the other, larger one. Although it was too dark to see the recognition on his face, it was perceptible: yes, this was him. That barrister shit.

‘Oh, damn it—the card!’ Alistair said. ‘Did I give you her card? Damn it! I bet I didn’t give it to you—and she wrote you a bloody card especially . . .’ He was rummaging in his pockets—patting them all twice.

To the figures in the darkness, it was as if he was playing for time. But he could have had no idea he might need to play for time—to him it was just the end of an evening.

‘Honestly,’ he said, ‘how typical of me. She wrote you a card—roses on the front, a window, a cat or something—she made me promise I wouldn’t forget . . .’

‘Well, you’re utterly useless, Al. None of us ever understood why she married you,’ the host said. He was a very tall, thin man, of the kind you imagine always got his glasses knocked off rather pathetically when he was younger and had arranged his life so it would never happen again. He laughed, just a little harder than was necessary. Then he slapped Alistair’s shoulder. ‘You just send her our love,’ he said.

‘I will, Julian.’

‘And you’re sure you don’t want a cab? Last chance . . . you must be over the limit.’

The smaller man felt his heart leap, heard his friend’s breath catch: after all this build-up, just to watch the bastard drive off in a cab, just to go on back to the flat with a couple of bags of Burger King . . .

‘No, no— really, I’m OK to drive,’ Alistair said, smiling.

The couple stood back in their doorway, framed by golden light, hands linked, a chandelier twinkling behind them. They looked wealthy and content while unseen faces wondered if they had ever been burgled.

The light from the door cut out behind Alistair’s heels and he set off towards the new dark blue BMW the two men had identified when they walked that way earlier. They had both wanted to key it, but the larger one said they should save it up—save it all up for later.

Now that the time had come, they padded after Alistair, watching him search his pockets for his car keys. Eventually he brought them out of his jacket—along with something else. They heard the tut and groan he made as he recognized the card in his hand. He was coming up to a rubbish bin and he slowed down, his hand moving uncertainly towards it, questioned by his conscience. Should he throw away the card and let his wife assume he had given it to their friends? ‘Suppressio veri or suggestio falsi?’ he asked himself mockingly, knowing he had told Rosalind many barefaced lies.

It was then that two figures jumped on him and altered the rarefied quality of his perspective for ever.

They moved quickly: one held his arms back, and the other smashed the baseball bat into his right leg, hard, five or six times. Alistair heard the bone shatter and felt himself crumple. It was an odd, involuntary movement—a dive into the wave of pain. When they dropped him on the pavement, one of them must have stumbled back into a parked car, because the last thing he remembered was the whir of an alarm going off and the headlights pulsing, illuminating the running figures in heartbeats of time.

Now Alistair limped off the cliff path and spotted the car, which would be hot enough to bake cakes in: he had left it, unwisely, in the sunlight. He would not have been able to drive his own car, but this one, which belonged to his wife, was an automatic and just about manageable with his bad leg. He started it and looped his way back into Dover past boarding-house after boarding-house, each one like a long-lost maiden aunt to him, shabbily coquettish behind her busy-lizzies.

Time had really passed since he was last in Dover. The Igglesdon Square bakery, with its litde tea-room—he could still taste the scones and jam, the sense of having been a good boy—was a sterile bookshop and stationer’s now. The Cafe de Paris, whose name had conjured so much nonsense, in which he had sat dreaming with an ordinary cup of tea and a book the whole year before he went to Oxford, had been demolished and forgotten. Beach Street, his old friend Tommy’s house, had been wiped out and replaced with a lorry park.

But all the old places had been there that morning in his mother’s photograph albums. Tucked into the front of one of them there had been a picture of a little white-haired woman with a cat on her lap. Apparently this was his mother. He would not have recognized her. The woman he had known was one with chestnut hair and heavy hips and pretty eyes. Where was the glass of sweet sherry or the cigarette in her hand? On the back of the photograph it said, ‘Dear June, thanks for a lovely day and a smashing lunch. October 2000.’ He felt a pang of jealousy, of exclusion. This thin woman with the cat was the person who had died five weeks ago. It had not occurred to him to wonder what his mother had looked like when she died. It was so hard to believe other people existed when you didn’t see them.

He and his mother had not spoken or touched each other in forty years. And yet there she had been, giving her friends lunch on an October afternoon. Her life had continued without him. She had owned a cat. Where was it? What had happened to her cat? he wondered.

When he and his son Luke arrived they had found the place in chaos. The hall ceiling had caved in and water had poured through it, ruining the carpet. He imagined the cat had probably run away in search of food. Had it watched its owner sleep tantalizingly through each mealtime, through three long days and nights, in a strange heap at the bottom of the stairs? It must have been a very quiet death, he thought, with only the cat for a witness.

It was not the way his mother’s life should have ended. Suddenly he felt that passionately and the colour came into his cheeks and his eyes glittered. He knew he had no right to this indignation. The prodigal son had no right to grieve. He had recently discovered that all his emotions were in rather poor taste.

He pulled up outside the house. Two Iraqi Kurdish men walked past, one carrying a split bin-bag of clothes; the arm of a red jumper hanging down and flapping behind his legs. The man stopped and turned. His profile was gaunt and handsome, rough-shaven. When he sucked out the last of his cigarette, his cheeks hollowed. He threw the butt into the bushes and adjusted the weight of the bag, lifting it on to his hip. Then he nodded to his friend and they moved on. They were obviously practised at accommodating each other’s checks and pauses. Perhaps they had done their long journey together. Was that bin-bag all they had brought?

The night before, he had seen news footage of a busload of asylum-seekers being deported from France. He remembered one man in the eye of the camera, twisted, crying, literally punching himself in the head, tearing out his hair. They had all been found squatting in a Parisian church and after several days of bureaucratic debate, of chanting crowds with homemade signs, of illuminated TV reporters and hunched cameramen, it was decided they had no right to be in Europe.

Alistair locked the car and walked towards his childhood home. He still expected to see the sign above it, ‘The Queen Elizabeth Guesthouse. Vacancies’, and the bright, flowery curtains in each window. But these things were as remote and obsolete as his childhood.

Apparently his mother had stopped running the guesthouse in 1980. She would then have been sixty-six. Just three years older than he was now. At one point, she had tried to sell the top half of the house as a flat, but no one had wanted to buy it. Dover was hardly a pleasure spot these days—just a place to be passed through, a place of temporary accommodation.

He had learnt these facts about the house from the legal documents he had been sent after his mother’s death. She had probably thought of living on the ground floor because of the trouble with her hips, he thought. He had learnt about her hips from the medical report.

His mother’s hips—the broad hips he had been carried about on, with his thumb in his mouth, feeling the folds of her cotton dress, the warmth of her soft waist and stomach, under his bare legs. At one time, he had not been himself but the most awkward part of her body. He could still remember the way she shifted him up more firmly as she leant towards the ashtray to tap her cigarette. She dealt with problems in twos always: you dusted with one hand, plumped the sofa cushions against your leg with the other. You swilled the old water out of the bedside carafes while you cleaned out the basin.

It startled him how often in his memory she was cleaning. Always cleaning. Turning down the beds, mopping the kitchen floor, reaching up for a cobweb with a pink feather duster. Or, most often, he saw her last thing of all on a Sunday afternoon, polishing the little ornaments in their own sitting room. He remembered a parrot on a swing from a trip to Bath (who knew why it had constituted a souvenir from Bath?), a silver cat licking its paw, a grinning shepherdess, thirty litde painted china boxes. He still felt the poignancy of her satisfaction when the sideboard shone and she could settle down with her Sunday glass of sherry. In his memory, the radio was going in the background through a coil of cigarette smoke.

His mother came back to him intact—with her curlers, her fears. He had never appreciated her fortitude before. Now each of his memories seemed to embody her supernatural determination to get the job done. Her life had been brutally subdued to fulfil a cheery set of principles: if a job’s worth doing, it’s worth doing well; idle hands are the devil’s playthings. He felt himself collapse inside with love and horror. The soul-destroying modesty of her expectations! This was what he had shaken off when he ran that last time for the train to London, slamming the window down as soon as he was on, taking huge gulps of air and listening to the wheels set off.

We don’t really move very far at all in life, he thought.

But how could he be blamed for thinking he had, for thinking he had been reborn on another planet? The home he and Rosalind had made in Holland Park with the thick damask curtains, the walnut side-tables, the heavy, silver-framed photographs of their children playing tennis and of the place they often took in Italy—every aspect of their lives was a product of the taste his wife had inherited. And that was exactly how he had wanted it. He had wanted to forget where he grew up and to lose himself in another person’s world. He had chosen a clean, ordered world with no smell of fried breakfasts or of large, unknown men.

‘Luke?’ he called, as he went into the cramped hallway. He could see his son through the back door, in the garden, smoking a cigarette and kicking at bits of loose turf. He watched Luke make a fist with his right hand and turn it over under his eyes as if he was calculating how powerful it might be. Alistair felt aware of violence stored up in people now. ‘Luke? I’m back.’

His son let the fist slacken and blew out a jet of smoke. ‘Just having a cig, Dad. Be there in a minute.’

‘No hurry,’ he called. Conversation was difficult with Luke. Always had been.

Alistair walked into his mother’s sitting room and looked at all the dusty ornaments. He had not attempted to ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Epigraph

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- About the Author

- Connect with HMH

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Exposure by Talitha Stevenson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.