- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

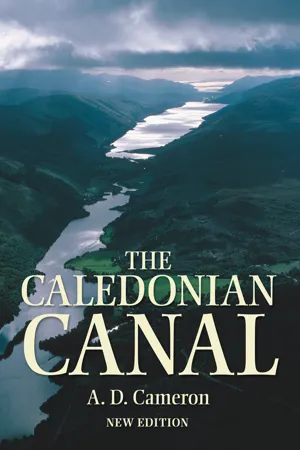

The Caledonian Canal

About this book

An exploration of the history of the sixty-mile, Scottish Highland canal and its significance to the region's transportation and tourism.

Thomas Telford's plan, to connect Loch Ness, Loch Oich, and Loch Lochy with each other and the sea, was a huge undertaking that brought civil engineering to the Highlands on a heroic scale. Deep in the Highlands, far from the canal network of England, engineers forged their way through the Great Glen to construct the biggest canal of its day: twenty-two miles of artificial cutting and no fewer than twenty-eight locks. A.D. (Sandy) Cameron's book has long been recognized as the authoritative work on the canal as well as a reliable and useful guide to the surrounding area. There are intriguing old plans, not discovered until 1992, and a survey of the dramatic rise in pleasure-craft traffic during the last two decades. But the highlight of the recent past was undoubtedly the Tall Ships passing through the canal in stately procession in 1991. Impossible, then, not to feel the fascination of this beautiful waterway: a working piece of industrial history and a remarkable engineering achievement. This book is a fitting celebration of this remarkable feat of engineering.

Thomas Telford's plan, to connect Loch Ness, Loch Oich, and Loch Lochy with each other and the sea, was a huge undertaking that brought civil engineering to the Highlands on a heroic scale. Deep in the Highlands, far from the canal network of England, engineers forged their way through the Great Glen to construct the biggest canal of its day: twenty-two miles of artificial cutting and no fewer than twenty-eight locks. A.D. (Sandy) Cameron's book has long been recognized as the authoritative work on the canal as well as a reliable and useful guide to the surrounding area. There are intriguing old plans, not discovered until 1992, and a survey of the dramatic rise in pleasure-craft traffic during the last two decades. But the highlight of the recent past was undoubtedly the Tall Ships passing through the canal in stately procession in 1991. Impossible, then, not to feel the fascination of this beautiful waterway: a working piece of industrial history and a remarkable engineering achievement. This book is a fitting celebration of this remarkable feat of engineering.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

THE OPENING OF THE CANAL

The Caledonian Canal was ceremonially opened when the first ship sailed through from Inverness to Fort William on 23–24 October 1822. On board were Mr Charles Grant, former MP for the County representing the Canal Commissioners, and an invited party of landed proprietors. The event was reported in the Inverness Courier in dignified prose, appropriate to the time and the occasion:

The doubters, the grumblers, the prophets and the sneerers, were all put to silence, or to shame; for the 24th of October was at length to witness the Western joined to the Eastern sea. Amid the hearty cheers of the crowd of Spectators assembled to witness the embarkation, and a salute from all the guns that could be mustered, the Voyagers departed from the Muirtown Locks (Inverness) at 11 o’clock on Wednesday with fine weather and in high spirits. In their progress through this beautiful Navigation they were joined from time to time by the Proprietors on both sides of the lakes; and as the neighbouring hamlets poured forth their inhabitants, at every inlet and promontory, tributary groups from the glens and the braes were stationed to behold the welcome pageant, and add their lively cheers to the thunder of the guns and the music of the Inverness-shire militia band, which accompanied the expedition . . . [At Glen Urquhart,] where a number of Highlanders were gathered, the Voyagers were joined by Mr Grant of Redcastle, Mr Grant of Corriemony, the Rev. Mr Smith of Urquhart and several other gentlemen. The reverberation of the firing, repeated and prolonged by a thousand echoes from the surrounding hills, glens and rocks – the martial music – the shouts of the Highlanders – and the answering cheers of the party on board, produced an effect which will not soon be forgotten by those present . . .

Other stops and salutes consumed more time and it took all of seven hours to reach Fort Augustus to the noise of more guns, more music and more congratulations. On Thursday, the party departed at six in the morning:

Tall ships entering Laggan Locks from Loch Lochy in July 1991.

Urquhart Castle on the most commanding site overlooking Loch Ness.

After sailing about five and a half miles in the Canal and passing through seven locks, the steam yacht entered Loch Oich. On approaching the mansion of Glengarry, the band struck up ‘My name it is Donald Macdonald’ etc. and a salute was fired in honour of the Chief, which was returned from the old castle, the now tenantless residence of Glengarry’s ancestors. The Ladies of the family stood in front of the modern mansion waving their handkerchiefs . . . The Voyagers were here joined by the Comet (11) steam-yacht . . . After passing through two locks, and a small portion of the Canal cut through the summit from which the land falls towards the East and West Sea, the yacht entered Loch Lochy . . . The groups of Highlanders (for all the huts of Lochaber must have been deserted), stationed upon picturesque and commanding points, added not a little to the interest and liveliness of the scene . . . The last portion of the Canal was now entered. It is eight miles in length and contains 12 locks. At Banavie, near Corpach, eight of these grand locks, which are close upon each other, have been fancifully denominated ‘Neptune’s Staircase’. It was half past five when the vessel at last dipped her keel into the waters of the Western Ocean, amidst the loud acclamations of her passengers and a great concourse of spectators! The termination of the voyage was marked by a grand salute from the Fort, whilst the Inhabitants of Fort William demonstrated their joy by kindling a large bonfire. A plentiful supply of whisky, given by the gentlemen of Fort William, did not in the least dampen the ardour of the populace. 67 gentlemen, the guests of Mr Grant, sat down to a handsome and plentiful dinner . . .

In this manner the Caledonian Canal was opened ‘from sea to sea’. The excitement of the spectators on shore was unrestrained because they had lived through the years of hard work that had gone into constructing it. Probably many of them had worked on it themselves, and they were delighted that it had that day proved itself serviceable. They had high hopes that it would be a safe route for ships for many years to come and that with ships would come trade and industry and a prosperous future.

What is significant about the opening party was that it consisted almost entirely of landed proprietors. They were still a power in the Highlands. Charles Grant must have had more than half the county’s eighty-three voters aboard, since only landowners had the right to vote at that time. He was unique amongst them in having been personally involved in promoting the Canal, as one of the Commissioners since its inception. One of the company, Alastair MacDonell of Glengarry, of whom more later, had been a greater obstacle to the completion of the Canal than the stubborn rock from which Corpach basin was hewn. Their mood of mutual congratulation expanded after dinner when, after several loyal toasts which were not enumerated by the reporter, no less than thirty-nine toasts were proposed and drunk – a reminder that the tax on whisky was only 6/2d a gallon.

They drank to many things – the prosperity of the Canal, Parliament’s generosity, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Canal Commissioners one by one, Chiefs and Clans, Inverness county and town – and to one another. It was not until the nineteenth toast that a word was said to praise the men who planned the Canal and the men who built it, when the Hon. William Fraser proposed ‘Mr Telford, and the gentlemen who carried on the operative part of the Caledonian Canal with so much credit to themselves.’

At 12 o’clock the party broke up, the Courier reporter tells us, but some gentlemen, ‘with genuine Highland spirit’, carried on into the early hours of the morning. The next day they completed the voyage back to Inverness in thirteen hours. So much for Highland spirit!

The Canal had been opened in two days: it had taken nineteen years and cost nearly a million pounds to build.

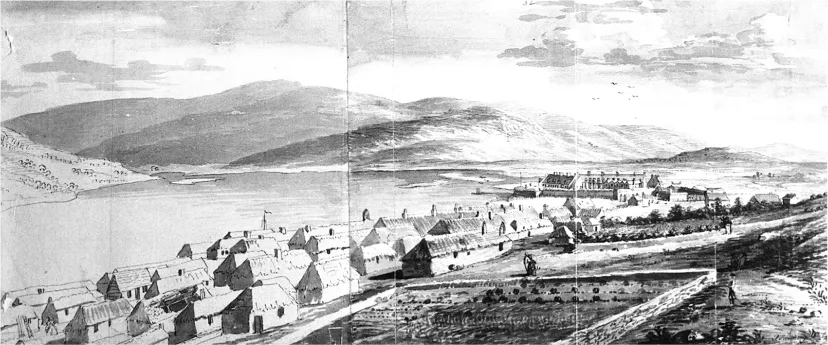

Looking from Fort William towards Loch Eil. The Canal entrance was made at Corpach behind the island in the left centre. The Fort is to the right with the Great Glen beyond. From Pennant’s Tour in Scotland (1769).

2

WHY BUILD A CANAL IN THE GREAT GLEN?

In a mountainous country with an indented coastline like Scotland, people had used the sea from the earliest times as the easiest means of communication. Most settlements were coastal and lines of penetration inland took advantage of firths and long sea lochs. The wealth of Bronze Age remains in the Great Glen, for example, shows that it attracted very early settlers, using river and loch to make their way inland and gain access to the east coast. Later, in the Middle Ages, most burghs in the Lowlands were created within the sound of the sea and traded with Europe and one another by sea. The Highlands, however, remained almost destitute of towns.

When the transport revolution came in England in the 1750s it started with the construction of canals to transport heavy goods like coal to the rising industrial towns. James Brindley’s canal from inside the coal mine at Worsley to Manchester set the pattern. Direct delivery in bulk from an inland mine to an inland destination proved that inventiveness and hard work could cut costs and helped to make the Industrial Revolution possible. During the sixty years of the reign of George III the navigable stretches of English rivers were joined with one another by canals until Manchester was linked with London, and Gloucester, if need be, with Hull. Inland waterways became the arteries of trade, financed by private enterprise and cut by navigators, later called ‘navvies’. Scotland, too, saw the construction of canals during this Canal Age.

The first project to be surveyed in Scotland was for a sea-to-sea canal across her narrow waist between the Forth and the Clyde. The second, the Monkland Canal, between Airdrie and Glasgow, was simply an artificial ditch dug with the aim of undercutting the coal prices charged by local mine-owners nearer to Glasgow. Work was going forward on both by 1770 and it was not surprising that thoughts were turning towards the prospect of cutting canals in many other parts of the country, even in the Highlands.

This is an example of how ideas for the improvement of a region at any time tend to follow current fashion. Projects which have proved successful earlier elsewhere are taken up and advocated with enthusiasm even where conditions are less favourable or, frankly, unfavourable. It was happening with estate improvement in the eighteenth century: the high returns received by improvers like Coke of Holkham in Norfolk were an incentive to others, but not something that was always achieved. It was happening with the foundation of factory villages, such as Stanley in Perthshire and Spinningdale in Sutherland, which had to compete with much larger units of production in Lancashire and Lanarkshire. It was to happen again much later with a proposal for a railway to Skye and the abortive railway between Spean Bridge and Fort Augustus which ran with few passengers along the south-western half of the Great Glen from 1903 to 1933 and was described by John Thomas in The West Highland Railway as ‘the classic example of the railway which should not have been built’.

At the time the cry everywhere was for canals and the Great Glen running from south-west to north-east from Fort William to Inverness looked as if it had been shaped by nature to make the canal-builder’s job easy. Where else in mountainous country in Britain was there a stretch of sixty miles involving a rise above sea level of only about a hundred feet? Which other area contained three long narrow lochs in a straight line capable of forming two-thirds of the waterway without human effort? Where else was there such heavy rainfall to swell the mountain streams and keep the water level high? What loch could compare with Loch Ness in length (22 miles) or in depth (129 fathoms), deeper than any part of the North Sea between Scotland and Denmark? The location was attractive and the prospect of a great navigation there to join the Atlantic with the North Sea was to many observers an intriguing possibility.

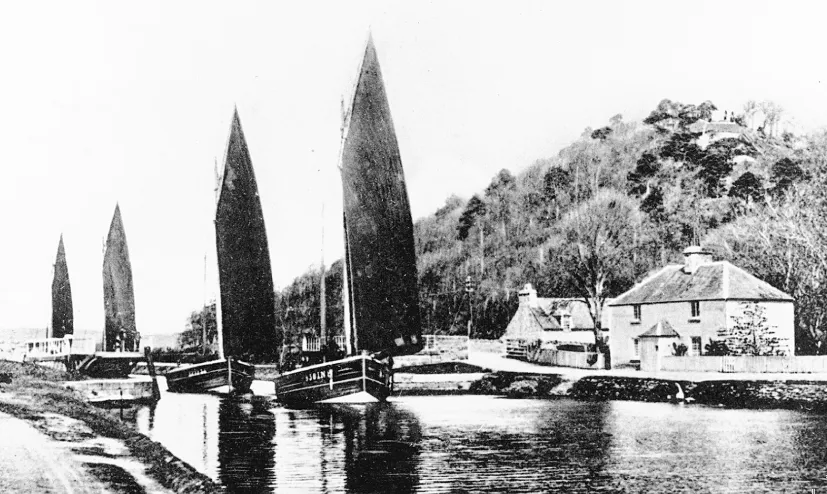

Fishing boats in full sail by the back of Tomnahurich: the Brahan Seer’s prophecy fulfilled.

Even in the seventeenth century the best-known Highland prophet, the Brahan Seer, predicted: ‘strange as it may seem to you this day, the time will come, and it is not far off, when full-rigged ships will be seen sailing eastward and westward by the back of Tomnahurich [inland] at Inverness’.

Old field patterns in Glen Roy with pastures beyond, typical of former ways of farming in the Great Glen.

The Corrieyairack, the greatest of Gener...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction and Acknowledgements (1st edn)

- Introduction and Acknowledgements (4th edn)

- 1 The Opening of the Canal

- 2 Why Build a Canal in the Great Glen?

- 3 Thomas Telford: The Man with Ideas

- 4 Choosing the Team

- 5 Making a Start in 1803

- 6 East End

- 7 West End

- 8 In the Centre

- 9 Completion under Criticism

- 10 Working the Canal – in the 1820s

- 11 Reconstructing the Canal – in the 1840s

- 12 Working the Canal – after Fifty Years

- 13 Working the Canal – after a Hundred Years

- 14 Working the Canal – after a Hundred and Fifty Years

- 15 Journey through the Canal in 1972

- 16 An Old Canal Restored

- 17 Changes in Canal Traffic

- Appendix I Canal Information

- Appendix II Places of Interest in the Great Glen

- Further Reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Caledonian Canal by A.D. Cameron in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.