- 299 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

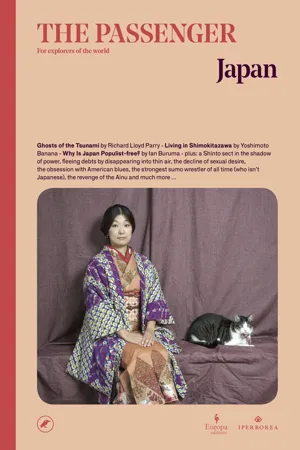

The Passenger: Japan

About this book

Explore Japanese society in the lively series that collects the best new writing, photography, art, and reportage from around the world.

Visitors from the West look with amazement, and sometimes concern, at Japan's social structures and unique, complex culture industry; the gigantic scale of its tech corporations and the resilience of its traditions; the extraordinary diversity of the subcultures that flourish in its "post-human" megacities. The country nonetheless remains an intricate and complicated jigsaw puzzle, an inexhaustible source of inspiration for stories, reflections, and reportage. Caught between an aging population and extreme post-modernity, Japan is an ideal observation point from which to understand our era and the one to come. The subjects in this volume form a portrait of the country that ranges from the Japanese veneration of the dead to the Tokyo music scene, from urban alienation to cinema, from sumo to toxic masculinity.

" The Passenger readers will find none of the typical travel guide sections on where to eat or what sights to see. Consider the books, rather, more like a literary vacation." — Publishers Weekly

In this volume: Ghosts of the Tsumani by Richard Lloyd Parry Living in Shimokitazawa by Yoshimoto Banana Why Japan Has Avoided Populism by Ian Buruma Plus: a Shinto sect in the shadow of power, fleeing debts by disappearing into thin air, the decline of sexual desire, the obsession with American blues, the strongest sumo wrestler of all time (who isn't Japanese), the revenge of the Ainu and much more . . .

Visitors from the West look with amazement, and sometimes concern, at Japan's social structures and unique, complex culture industry; the gigantic scale of its tech corporations and the resilience of its traditions; the extraordinary diversity of the subcultures that flourish in its "post-human" megacities. The country nonetheless remains an intricate and complicated jigsaw puzzle, an inexhaustible source of inspiration for stories, reflections, and reportage. Caught between an aging population and extreme post-modernity, Japan is an ideal observation point from which to understand our era and the one to come. The subjects in this volume form a portrait of the country that ranges from the Japanese veneration of the dead to the Tokyo music scene, from urban alienation to cinema, from sumo to toxic masculinity.

" The Passenger readers will find none of the typical travel guide sections on where to eat or what sights to see. Consider the books, rather, more like a literary vacation." — Publishers Weekly

In this volume: Ghosts of the Tsumani by Richard Lloyd Parry Living in Shimokitazawa by Yoshimoto Banana Why Japan Has Avoided Populism by Ian Buruma Plus: a Shinto sect in the shadow of power, fleeing debts by disappearing into thin air, the decline of sexual desire, the obsession with American blues, the strongest sumo wrestler of all time (who isn't Japanese), the revenge of the Ainu and much more . . .

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Passenger: Japan by The Passenger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Japanese History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A cut-out of a sumo wrestler outside the Kokugikan, Japan’s national sumo stadium.

Sea of Crises

A writer’s journey to follow the most important tournament in the sumo calendar – with all its rituals and strict hierarchies – becomes a voyage into events buried in the past. Brian Phillips finds himself tracking a forgotten man, one who, in 1970, was involved in another ritual, a sensational case of seppuku, when he decapitated the writer Mishima Yukio following a failed coup d’état.

BRIAN PHILLIPS is an author and journalist with a passion for sport who works as a senior writer for MTV News. He has contributed to Grantland, The New York Times, The New Republic and Slate, as well as being included in the Best American Sports Writing and Best American Magazine Writing anthologies. This article is taken from his debut book Impossible Owls, a collection of narrative essays first published by FSG Originals in 2018. He lives in Los Angeles.

When he comes into the ring, Hakuhō, the greatest sumōtori in the world, perhaps the greatest in the history of the world, dances like a tropical bird, like a bird of paradise. Flanked by two attendants – his tachimochi, who carries his sword, and his tsuyuharai, or dew sweeper, who keeps the way clear for him – and wearing his embroidered apron, the keshō-mawashi, with its braided cords and intricate loops of rope, Hakuhō climbs on to the trapezoidal block of clay, sixty centimetres high and nearly seven metres across, where he will be fighting. Here, marked off by rice-straw bales, is the circle, the dohyō, which he has been trained to imagine as the top of a skyscraper: one step over the line and he is dead. A Shinto priest purified the dohyō before the tournament; above, a six-tonne canopy suspended from the arena’s ceiling, a kind of floating temple roof, marks it as a sacred space. Coloured tassels hang from the canopy’s corners, representing the Four Divine Beasts of the Chinese constellations: the azure dragon of the east, the vermilion sparrow of the south, the white tiger of the west, the black tortoise of the north. Over the canopy, off-centre and lit with spotlights, flies the white-and-red flag of Japan.

Hakuhō bends into a deep squat. He claps twice then rubs his hands together. He turns his palms slowly upwards. He is bare chested, 1.95 metres tall and weighs 158 kilograms. His hair is pulled up in a topknot. His smooth stomach strains against the coiled belt at his waist, the literal referent of his rank: yokozuna, horizontal rope. Rising, he lifts his right arm diagonally, palm down, to show he is unarmed. He repeats the gesture with his left. He lifts his right leg high into the air, tipping his torso to the left like a watering can, then slams his foot on to the clay. When it strikes, the crowd of thirteen thousand souls inside the Ryōgoku Kokugikan, Japan’s national sumo stadium, shouts in unison: ‘Yoisho! – Come on! Do it!’ He slams down his other foot: ‘Yoisho!’ It’s as if the force of his weight is striking the crowd in the stomach. Then he squats again, arms held out wing-like at his sides, and bends forward at the waist until his back is near parallel with the floor. Imagine someone playing aeroplanes with a small child. With weird, sliding thrusts of his feet, he inches forward, gliding across the ring’s sand, raising and lowering his head in a way that’s vaguely serpentine while slowly straightening his back. By the time he’s upright again, the crowd is roaring.

*

Since 1749 sixty-nine men have been promoted to yokozuna. Only the holders of sumo’s highest rank are allowed to make entrances like this. Officially, the purpose of the elaborate dohyō-iri is to chase away demons. (And this is something you should register about sumo, a sport with TV contracts and millions in revenue and fan blogs and athletes in yogurt commercials – that it’s simultaneously a sport in which demon-frightening can be something’s official purpose.) But the ceremony is territorial on a human level, too. It’s a message delivered to adversaries, a way of saying, This ring is mine; a way of saying, Be prepared for what happens if you’re crazy enough to enter it.

A cut-out of a sumo wrestler.

Hakuhō is not Hakuhō’s real name. Sumo wrestlers fight under ring names called shikona, formal pseudonyms governed, like everything else in sumo, by elaborate traditions and rules. Hakuhō was born Mönkhbatyn Davaajargal in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, in 1985; he is the fourth non-Japanese wrestler to attain yokozuna status. Until the last thirty years or so, foreigners were rare in the upper ranks of sumo in Japan. But some countries have their own sumo customs, brought over by immigrants, and others have sports that are very like sumo. Thomas Edison filmed sumo matches in Hawaii as early as 1903. Mongolian wrestling involves many of the same skills and concepts. In recent years wrestlers brought up in places such as these have found their way to Japan in greater numbers and have largely supplanted Japanese wrestlers at the top of the rankings. At the time of writing, six of the past eight yokozuna promotions have gone to foreigners, with no active Japanese yokozuna since the last retired in 2003. This is a source of intense anxiety to many in the tradition-minded world of sumo in Japan.

As a child, the story goes, Davaajargal was skinny. This was years before he became Hakuhō, when he used to mooch around Ulaanbaatar, thumbing through sumo magazines and fantasising about growing as big as a house. His father had been a dominant force in Mongolian wrestling in the 1960s and 1970s, winning a silver medal at the 1968 Olympics and rising to the rank of undefeatable giant. It was sumo that captured Davaajargal’s imagination, but he was simply too small for it.

When he went to Tokyo, in October 2000, he was a 62-kilo fifteen-year-old. No trainer would touch him. Sumo apprentices start young, moving into training stables called heya where they’re given room and board in return for a somewhat horrifying life of eating, chores, training, eating and serving as quasi-slaves to their senior stablemates (and eating). Everyone agreed that little Davaajargal had a stellar wrestling brain, but he was starting too late, and his reed-like body would make real wrestlers want to kick dohyō sand in his face. Finally, an expat Mongolian rikishi (another word for sumo wrestler) persuaded the master of the Miyagino heya to take Davaajargal in on the last day of the teenager’s stay in Japan. The stablemaster’s gamble paid off. After a few years of training and a fortuitous late growth spurt, Davaajargal emerged as the most feared young rikishi in Japan. He was given the name Hakuhō, which means White Peng (a Peng being a giant bird in Chinese mythology).

A row of mawashi, the loincloths worn by sumo wrestlers, in the gym where members of the student sumo club train at Asahi University, Gifu Prefecture.

Students gathered around their trainer before daily practice.

‘Sumo apprentices start young, moving into training stables where they’re given room and board in return for a life of eating, chores, training, eating and serving as quasi-slaves to their senior stablemates (and eating).’

Hakuhō’s early career was marked by a sometimes bad-tempered rivalry with an older wrestler, a fellow Mongolian called Asashōryū (Morning Blue Dragon), who became a yokozuna in 2003. Asashōryū embodied everything the Japanese fear about the wave of foreign rikishi who now dominate the sport. He was hot headed, unpredictable and indifferent to the ancient traditions of a sport that’s been part of the Japanese national consciousness for as long as there’s been a Japan.

This is something else you should register about sumo: it is very, very old. Not old like black-and-white movies; old like the mists of time. Sumo was already ancient when the current ranking system came into being in the mid-1700s. The artistry of the banzuke, the traditional ranking sheet, has given rise to an entire school of calligraphy.

Asashōryū brawled with other wrestlers in the communal baths. He barked at referees – an almost unthinkable offence. He pulled another wrestler’s hair, a breach that made him the first yokozuna ever to be disqualified from a match. Rikishi are expected to wear kimonos and sandals in public; Asashōryū would show up in a business suit. He would show up drunk. He would accept his prize money with the wrong hand.

The 287-kilo Hawaiian sumōtori Konishiki launched a rap career after retiring from the sport; another Hawaiian, Akebono, the first foreign yokozuna, became a professional wrestler. This was bad enough. But Asashōryū flouted the dignity of the sumo association while still an active rikishi. He withdrew from a summer tour claiming an injury, then showed up on Mongolian TV playing in a charity soccer match. When sumo was rocked by a massive match-fixing scandal in the mid-2000s, a tabloid magazine reported that Asashōryū had paid his opponents US$10,000 per match to let him win one tournament. Along with several other wrestlers, Asashōryū won a settlement against the magazine, but even that victory carried a faint whiff of scandal: the Mongolian became the first yokozuna ever to appear in court. ‘Everyone talks about dignity,’ Asashōryū complained when he retired, ‘but when I went into the ring I felt fierce like a devil.’ Once, after an especially contentious bout, he reportedly went into the car park and attacked his adversary’s car.

The problem, from the perspective of the traditionalists who control Japanese sumo, was that Asashōryū also won. He won relentlessly. He laid waste to the sport. Until Hakuhō came along he was, by an enormous margin, the best wrestler in the world. The sumo calendar revolves around six grand tournaments – honbasho – held every two months throughout the year. In 2004 Asashōryū won five of them, two with perfect 15-0 records, a mark that no one had achieved since the mid-1990s. In 2005 he became the first wrestler to win all six honbasho in a single year. He would lift 180-kilogram wrestlers off their feet and hurl them, writhing, to the clay. He would bludgeon them with hands toughened by countless hours of striking the teppō, a wooden shaft as thick as a telephone pole. He won his twenty-fifth tournament, then good for third on the all-time list, before his thirtieth birthday.

Hakuhō began to make waves around the peak of Asashōryū’s invulnerable reign. Five years younger than his rival, Hakuhō was temperamentally his opposite: solemn, silent, difficult to read. ‘More Japanese than the Japanese’ – this is what people say about him. Asashōryū made sumo look wild and furious; Hakuhō was fathomlessly calm. He seemed to have an innate sense of angles and counterweights, how to shift his hips almost imperceptibly to annihilate his enemy’s balance. In concept, winning a sumo bout is simple: either make your opponent step outside the ring or make him touch the ground with any part of his body besides the soles of his feet. When Hakuhō won, how he’d done it was sometimes a mystery. The other wrestler would go staggering out of what looked like an even grapple. When Hakuhō needed to, he could be overpowering. He didn’t often need to.

The flaming circus of Asashōryū’s career was good for TV ratings. But Hakuhō was a way forward for a scandal-torn sport – a foreign rikishi with deep feelings for Japanese tradition, a figure who could unite the past and future. At first he lost to Asashōryū more than he won, but the rivalry always ran hot. In 2008, almost exactly a year after the Yokozuna Deliberation Council promoted Hakuhō to the top rank, Asashōryū gave him an extra shove after hurling him down in a tournament. The two momentarily squared off. In the video of the bout you can see the older man grinning and shaking his head while Hakuhō glares at him with an air of outraged grace. Over time Hakuhō’s fearsome technique and Asashōryū’s endless seesawing between injury and controversy turned the tide in the younger wrestler’s favour. When Asashōryū retired unexpectedly in 2010 after allegedly breaking a man’s nose outside a nightclub, Hakuhō had taken their last seven regulation matches and notched a 14-13 lifetime record against his formerly invincible adversary.

With no Asashōryū to contend with, Hakuhō proceeded to go 15-0 in his next four tournaments. He began a spell of dominance that not even Asashōryū could have matched. In 2010 he compiled the second-longest winning streak in sumo history, sixty-three straight wins, which tied a record set in the 1780s. By 2014 he had won a record ten tournaments without dropping a single match.

*

Watching Hakuhō’s ring entrance, that harrowing bird dance, it is hard to imagine what his life is like. To have doubled in size, more than doubled, in the years since his fifteenth birthday; to have jumped cultures and languages; to have unlocked this arcane ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Japan in Numbers

- The Mythbuster — Tania Palmieri

- The Number — Matteo Battarra

- Ghosts of the Tsunami — Richard Lloyd Parry

- The ‘Do-it-Yourself’ Women — Sekiguchi Ryōko

- The (No Longer So) Secret Cult that Governs Japan — Jake Adelstein

- Why Japan Is Populist-Free — Ian Buruma

- A Simple Thank You — Yoshimoto Banana

- The Withering of Desire — Murakami Ryū

- Of Bears and Men — Cesare Alemanni

- Sea of Crises — Brian Phillips

- Sweet Bitter Blues — Amanda Petrusich

- Family Album — Giorgio Amitrano

- The Evaporated — Léna Mauger

- The Iconic Object — Giacomo Donati

- The National Obsession — Matteo Battarra

- The Phenomenon — Cesare Alemanni

- An Author Recommends — Furukawa Hideo

- The Playlist — Furukawa Hideo

- Further Reading

- Copyright