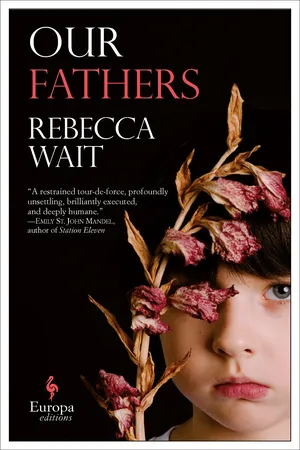

![]() OUR FATHERS

OUR FATHERS![]() PART 1

PART 1![]()

1

When Gavin McKenzie came home from the pub, wiping his boots on the mat with that slow deliberation that meant he was half-cut, he said to his wife, “Tommy Baird’s back on the island.”

It wasn’t that she didn’t recognize the name; no one would forget a thing like that. But the mention of it was so unexpected that for a few seconds Fiona’s mind was blank. Then she saw him again, his serious little face as he stood in the shop with his mother, those bright cagoules he and his brother wore. Fiona was sixty-three, but her memory was as sharp as ever.

“Wee Tommy Baird?” she said. “Surely not.”

“He’s not so wee now,” Gavin said, taking off his wet coat and disappearing for a moment as he went to hang it up. “Must be thirty or more,” his voice came from the hallway.

Fiona was silent, calculating. Her own Stuart was thirty-nine this year. Already on his second marriage, the one they hoped might stick, though they’d liked Joanne very much. “Thirty-one,” she brought out. “I think he must be thirty-one.” She stopped, trying to take it in. Then, “What’s he doing back here?”

Gavin, coming into the room, shrugged. “I know no more than you,” he said, which was absurd given that he was the one telling her the news. “Ross saw him on the ferry this morning, coming over from Oban.”

Fiona allowed herself to relax a little at this. “Well, if it was only Ross! Are we to take his word for everything now? He’d barely know his own wife if she was standing beside him.”

“He spoke to him,” Gavin said, leaning against the doorframe. “Ross spoke to Tommy. There were only the two of them on the ferry. You know how Ross is, seeing a stranger, especially this time of year. Went up and introduced himself. Asked Tommy if he was on holiday.”

“And Tommy—he said who he was?” Fiona said.

“Aye. Though Ross said he’d worked it out already, soon as he got closer, before Tommy even spoke.”

Fiona couldn’t explain why she suddenly felt hot and cold all over. “Ross is all talk,” she said. Then, as another thought occurred to her, “He might be lying. The stranger.”

Gavin did that frown of his she hated, and which he seemed to reserve especially for her; it wasn’t contemptuous, Gavin was too gentle for that, but his look of utter bafflement felt worse, as though he was still amazed, after all this time, at the silly things she said. “Now why on earth would someone lie about a thing like that?”

Fiona had no answer for this. If there was one thing she’d learned from the Baird tragedy, it was that people acted in ways that could not be explained, that sometimes could barely even be imagined. “But why come back now?”

“I expect he’s visiting Malcolm.”

“Malcolm hasn’t seen him in years.”

“Still, family’s family.”

Fiona thought, but did not say, that ‘family’ might have a more complicated meaning for Tommy Baird than it did for the rest of them.

Gavin stomped through to the kitchen and Fiona heard him clattering about, making tea. “I’ll have a cup too,” she called, not holding out high hopes of receiving one; he was getting deafer by the year and he didn’t make one for her routinely anymore. Other women her age joked about having trained their husbands up nicely, but with Fiona it seemed to have gone the other way.

However, a few minutes later he did bring two mugs through, placing hers, a little sloppily, on the table beside her before he settled into his own armchair by the fire.

“The funny thing is,” he said, as though there had been no pause in their conversation, “Malcolm never said anything about it. He was in the bar yesterday and he didn’t say a word about Tommy coming.”

“Maybe he wasn’t expecting him,” Fiona said, further alarmed at this idea.

There was a long silence, broken only by Gavin slurping his tea. Fiona tried to focus on the crackling of the fire and not the wet sounds coming from her husband. It was a technique she’d taught herself years before. And she reminded herself that he was a good man, that he was kind, that he’d always been patient with Stuart. That patience wasn’t the same as weakness.

“Tommy Baird,” Gavin said eventually, in a meditative way. “I never felt right about him.”

“What do you mean?” Fiona said, the hot and cold feeling back.

“I felt like—we should have known, somehow. Don’t you think? We should have known. Done something, maybe.”

“Don’t be stupid,” Fiona said, more angrily than she’d intended. “What could we have done?” Firmly, with the air of someone closing the discussion, she said, “It doesn’t help to dwell on a terrible thing like that.”

She had seen that family almost every day, almost every day for ten years, and she had missed it all. She could never have predicted—but nobody could.

And she remembered Tommy afterwards, too. She saw him at ten or eleven, his face contorted in rage, hurling something at her—a vase, had it been? Something of Heather’s, something that had smashed just beside her head. He was a demon by then.

“Shall we have some of the coffee cake?” she said to Gavin, trying to soften the way she’d spoken before, trying to quieten the memory of Tommy. “It’ll be stale before we’re halfway through it.”

“Aye,” he said. “That’d be nice.”

There could have been no predicting what happened, Fiona told herself again as she went into the kitchen and got the tin down from the larder, cut Gavin a large slice and herself a small one. And in any case, as she always reassured herself (it wasn’t very reassuring), nobody ever knew what went on behind closed doors.

![]()

2

No, Malcolm wasn’t expecting him. When he opened the door in the late afternoon, the darkness already thickening, and saw Tommy standing there, he was so shocked that for a few moments he couldn’t even speak.

Of course, Tommy looked different. He was a grown man now, utterly transformed from when he’d last stood there. But Malcolm would know him anywhere, even after all this time. The worst of it was this: the boy hadn’t grown up to look like Katrina. No, it was John he resembled, with those dark brown eyes, the hard lines of his jaw. Tommy had the same light build as his father, too. The overall resemblance was uncanny. Malcolm could only hope Tommy didn’t realize.

It had been raining, though only lightly—a rare kind of rain for them here. But the man on his doorstep wasn’t properly dressed for any kind of weather in the Hebrides, wearing only jeans and a jersey, with trainers on his feet (the thin canvas kind, too). There was a rucksack on his shoulder, but it didn’t look to Malcolm like it could have much in it—certainly not proper boots and a waterproof.

“Tommy,” Malcolm said, because now that seemed like the only possible thing to say.

And the man said, meeting his eye and then not meeting it again, “Hello, Malcolm.”

There was a short silence, then Malcolm said, “Won’t you come in?” It was the phrase Heather would have used, and for a few seconds he was breathless with missing her. But he was distracted by this stranger—not a stranger, not really—stepping past him across the threshold, and then Tommy was standing in his house for the first time in twenty years.

Tommy said, “I hope you don’t mind . . .” Then he stopped, looking around the narrow hallway as though surprised to find himself there. It must seem even smaller to him now, Malcolm thought—the adult Tommy took up so much more space than the child.

Tommy put his hands in his pockets and rolled his shoulders back. Then he began again. “I know it’s weird, just turning up here. I should have called, or written a letter, or . . . emailed or something.” He gave a short laugh that didn’t sound like a laugh. “Of course, I don’t have your email. Not your phone number, either. Couldn’t find it.”

“I don’t have email,” Malcolm said, thinking how strange it was to hear a man’s deep voice coming from Tommy, coming out from behind a man’s face—John’s face. Tommy’s accent was unexpected too. It was unplaceable, not quite Scottish, not quite English, carrying only the faintest inflection of his past. “Never really caught up with all that,” Malcolm added, realizing he’d been silent for too long. “Heather was better at it. She had her own email account, her own laptop.” He stopped, aware that now he was only talking to fill up the space around his discomfort.

“Where is Heather?” Tommy said, looking past Malcolm towards the kitchen, as though she might actually be waiting there. And Malcolm realized with a lurch like rising sickness that Tommy knew nothing, knew absolutely nothing, that they had been cut off from one another so completely that Tommy might as well have been laid beneath the earth all these years, to now suddenly reappear, to come back from the dead and stand calmly in Malcolm’s hallway, brushing off the dirt and asking about Heather.

No way to soften it, not for either of them. “She died,” Malcolm said. “Almost six years ago now.” The words weren’t so worn around the edges that they didn’t hurt him. He had made a final attempt, after Heather’s death, to contact Tommy, but found that the only number he had, which was for Tommy’s cousin Henry, no longer worked. He had been too bound up in his own grief to feel much dismay at the time. Anyway, he had given Tommy up long ago.

“A stroke,” he told Tommy now. “Two, in fact. Both bad. She survived a few years after the first, but then she had another.” Then he added, because Tommy was staring at him without speaking, “She was still herself though. Right up to the end.”

“But—she must have been young,” Tommy said, and Malcolm was surprised to see him stricken like this. Because what had Heather been to Tommy in the end?

“Aye,” Malcolm said. “Too young.”

Tommy was silent.

Malcolm remembered himself and said, “Come on into the kitchen. You’ll have a cup of tea?”

“Yes. Please.”

“Put your bag down there for now,” Malcolm said, nodding towards the boot rack by the door, and Tommy did as he was told before following Malcolm through to the small kitchen.

How long would he be staying? Malcolm wondered, trying not to feel panicked. He’d have to stay two nights, at least; there wasn’t a ferry back to the mainland until Friday. The spare room was in a state—full of dust, with books and clutter piled up to the ceiling. Malcolm tried to think what Heather would do. Nothing could ever fluster his wife. She would tell him to take it one step at a time and make the lad some tea. So while Tommy sat at the table, Malcolm steadied himself with the fam...