- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Our future is closely tied to that of the variety of life on Earth, and yet there is no greater threat to it than us. From population explosions and habitat destruction to climate change and mass extinctions, John Spicer explores the causes and consequences of our biodiversity crisis. In this revised and updated edition, he examines how grave the situation has become over the past decade and outlines what we must do now to protect and preserve not just nature's wonders but the essential services that biodiversity provides for us, seemingly for nothing.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Biodiversity by John Spicer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The pandemic of wounded biodiversity

Looking back, you can usually find the moment of the birth of a new era, whereas, when it happened, it was one day hooked on to the tail of another.

John Steinbeck, Sweet Thursday

Biodiversity – what was that again?

Until recently global climate change was never far from the news. There was talk of setting and reaching emission targets, and global school strikes, and international meetings to agree ways forward, all of them receiving good air time. Biodiversity was there too, but more in the background, belying its importance. However, at the beginning of 2020 both climate change and biodiversity seemed to disappear from the scene in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic as the world struggled to work out how to respond to this new and global threat.

Even in the early months of the crisis, it was mooted that the appearance of SARS-CoV-2 was linked with biodiversity and particularly with biodiversity loss. Of all emerging infectious diseases in humans, 75% are transferred from animals to people – what we refer to as zoonotic diseases. Pathogens (microorganisms that cause disease) are more likely to make that jump where there are changes in the environment, like deforestation, and when natural systems are under stress from human activity and climate change. In the midst of a pandemic that many suspected was linked to biodiversity loss, we had to face our ignorance of what the fundamental relationship between biodiversity and human health actually looked like. We are only beginning to form a detailed understanding of many aspects of biodiversity, including how life and our planet work, and the effects we are having on that working.

At the same time, tales of ecological recovery filled our TV screens and populated the newspapers – ‘“Nature is taking back Venice”: wildlife returns to tourist-free city’. Some good news in a very dark time. Biodiversity bouncing back quickly when we’re forced to let up on the stress we put it under.

What is now clear is that issues around what biodiversity is, what we are doing to it, and how we best maintain it are not going to go away, pandemic or not. Knowing about and understanding biodiversity is interesting in its own right. But more and more it is becoming clear that, no matter who you are, biodiversity matters – and because it matters it is worth knowing as much about it as possible and understanding it better, if we are to make lives for ourselves in the coming decades.

That said, trying to pin down exactly what we mean when we talk of biodiversity is challenging. It seems to mean different things to different people. Here is a word that many would agree is important to get to grips with, but which few of us, when we reflect on it, have a good handle on.

There are a number of reasonable definitions of biodiversity – over 80 of them in fact! Many have merit or offer a slightly different take on the notion. Fortunately, there is one definition that has gained international currency, signed up to by the 150 nations that put together the Convention on Biological Diversity at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1992. Here biodiversity was defined as ‘the variability among living organisms from all sources including [among other things] terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are a part…[including] diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems’. In short, biodiversity is the variety of life – in all its manifestations. This sounds quite satisfying until we ask the million-dollar question. The question that reveals the extent to which the study of biodiversity is a science: how do we measure it? This is not so straightforward. And yet it goes to the very heart of what we mean when we talk about biodiversity or when we refer to the biodiversity of a particular area, country or region. A simple illustration will help us see where the challenges lie.

A long, leisurely trip to La Jolla

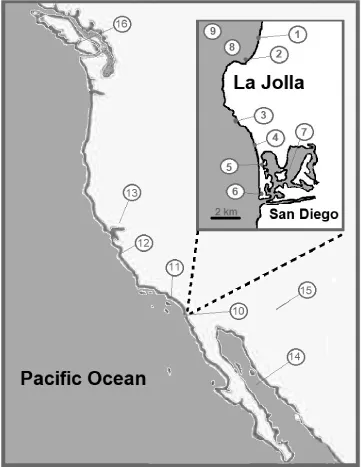

For as long as I can remember I have been fascinated by the seashore and the living creatures found there. Without doubt one of my favourite locations in the whole world (rivalling even the perfect beaches of my childhood on the west coast of Scotland) is the rocky shore at La Jolla, just north of San Diego, Southern California (SoCal) (Fig. 1). Bird Rock is a beach which gives its name to a small community at the north end of Pacific Beach and at the south end of La Jolla (Fig. 2). The coast that skirts the land was recognised as an area of special biological significance back in the 1970s with the designation of the San Diego–La Jolla Ecological Reserve. This reserve is now part of the larger La Jolla Marine Conservation Area and Bird Rock itself is within the South La Jolla State Marine Reserve, established less than a decade ago.

I first discovered Bird Rock beach and its intertidal life in 1994. Carefully negotiating the uneven shore around Bird Rock, following the outgoing tide and discovering the huge variety of marine life present, particularly in deep crevices and glistening tide pools, is an unforgettable experience. The biodiversity of Bird Rock is impressive, stunning even. As Ed Ricketts and Jack Calvin say in the preface to the first edition of their Between Pacific Tides (1939), ‘our visitor to a rocky shore at low tide has entered possibly the most prolific zone in the world.’ Between the tides (and maybe just above them), and in particular those that rise and fall on Bird Rock, nearly all the different major ‘types’ or ‘designs’ of the things that characterise life on Earth can be found. Even nearby rocks contain spectacular fossils of relatives of the present-day squid, as well as clams, snails and lamp shells – the remains of ancient marine biodiversity that lived here about 80 million years (or Ma, an abbreviation we will use from now on) ago. Here we have ‘life, and life in abundance’.

Figure 1 Location of Bird Rock in relation to other places in, or near, La Jolla (inset) and the north-east Pacific coast: 1) Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of San Diego, 2) La Jolla Cove, 3) Bird Rock, 4) Pacific Beach, 5) Mission Beach north (the Mission restaurant), 6) Mission Beach south, 7) Mission Bay, 8) San Diego–La Jolla Ecological Reserve, 9) La Jolla deep-sea canyon, 10) San Diego, 11) Newport Beach, with the San Pedro Channel between there and Santa Catalina Island to the south, 12) Monterey, 13) Jepson Prairie, Solano County, 14) Gulf of California (Mexico), 15) Site of Biosphere 2, Oracle (Arizona), 16) Bamfield Marine Station, Vancouver Island (Canada).

Figure 2 Bird Rock with the tide receding (November 2018 © John Spicer).

So let’s return to where we started, ‘How do we measure biodiversity?’ and in this case let’s say the biodiversity of Bird Rock specifically. How do we go about answering this question?

Could simply counting how many different types of living things there are do? This sounds like a possibility – but it’s no mean task. It could potentially take not just weeks and months but years, maybe tens of years, even for such a small area – and that’s leaving out all of the land animals, plants and microbes that form the larger landscape that is La Jolla. It is just about conceivable that for most of the largish marine animals, seaweeds and maritime plants we could put this list together. The California State Water Resources Control Board carried out a survey of life on the intertidal rocky shores within the San Diego–La Jolla Ecological Reserve in 1979. Close to Bird Rock they recorded fifty-three animal, nineteen seaweed and one flowering plant species, a total of seventy-three. This is a good start but still a huge underestimate of what is there, even based on my own visits. The marine life of these shores is, compared with similar beaches in other countries, relatively well known. This is largely because of the efforts of Ricketts and countless other marine biologists and naturalists, including those who have worked and studied (and still do) at the world-leading Scripps Institution of Oceanography, just north of Bird Rock, in La Jolla. However, for many microscopic animals, plants, fungi, bacteria and viruses our current information, while growing, is sketchy at best. It’s not just the process of finding them that is problematic either. Many of these little specks of life are yet to be described, let alone the number of different types counted.

Even if it were possible to count the numbers of different types of living things, would such a list really be a measure of the biodiversity of Bird Rock? Well, perhaps. But it ignores the fact that there are rarely equal numbers of each of the living things present. Some organisms are extremely numerous and ubiquitous, while others are rare or only occur in particular, sometimes very localised, areas. In most cases, their numbers fluctuate throughout the year, or over even greater timescales. Periwinkles are absolutely everywhere, sometimes in large piles. Octopus can be found but there are not as many individuals as the periwinkles. Microbes may occur in tens of millions, outnumbering everything else many times over. Surely biodiversity must encompass not just differences but the actual numbers of different things present? So is it all about numbers or is it about difference – or is it both?

Up until now the differences we’ve considered are based on what an organism looks like and how that separates it from others. It doesn’t take into account other differences that may be equally, maybe even more, important. Differences in genetics (the study of genes and their constituents, their heritability and variability) could be used to estimate how many things are there irrespective of whether they are big or small, identical in form, or difficult to tell apart. We could also use differences in the way individual types of organism ‘work’. For example, how they acquire energy and what they do with that energy to maintain themselves. Also, what they actually contribute (if anything?) to the working of the living community to which they belong. We know that at Bird Rock limpets and sea urchins, two totally different types of animal, can do the same sort of thing – they do what cows do on land, they graze. Maybe taking into account what species do in an area is the key feature in any measure of biodiversity? And then there are the interrelationships between species. There are predators (the eaters) and there are prey (the eaten), for example. And what about the many thousands of parasites that live within the microbes, animals and seaweeds on the beach? In fact, there are a multitude of ways in which species and even groups of species influence other species or groups. And shouldn’t the way living things work and interact, and the sum total of that – how an ecosystem functions – be more central to any measure of biodiversity we use? If we do take such a big-scale approach, what functions do we choose and why? And where do we factor in how visitors to the area interact with the living things on the beach, and how Bird Rock as a community of humans impacts on this small ecosystem, and how the beaches nearby, and the deep-water canyon nearby and all their inhabitants impact and influence the beach? And what about…and what about…and what about.

If you’ve been following all this, you may now find yourself at a mental crossroads. This is a well-trodden path. It is a place where many scientists, philosophers and theologians frequently find themselves. A place we will return to time and time again in the pages that follow. You can go down the ‘oh, but the world’s a complicated place’ path: this grows into the ‘we’ll never get to grips with it’ road, which leads to a comfy armchair, subdued lighting, a stiff drink, and an abandoning of intellectual pursuit and its travelling companion hope. Or you can opt for the ‘okay, it’s complicated, but…’ path: a path where you may never find the truth (easily more difficult to define than biodiversity), but you are happy to settle for slightly less if it prevents you from stalling and keeps you walking, moving forward. The truth is there is no one way of measuring or quantifying biodiversity. We cannot measure the biodiversity of Bird Rock, or any other stretch of coastline, or of the ocean,* or of our planet for that matter. We can talk and think about the notion of biodiversity, but we cannot measure it – we can only measure selected aspects of it. Don’t despair though. It may not be ideal – but even this is a good start.

Directions

To put together any beginner’s guide to biodiversity, drawing on current scientific knowledge and understanding, much of our time will be spent looking at measures of biodiversity and how those measures change in time and space. Some measures will be better, or more appropriate, than others. In many cases we will find that the measure has been decided for us. Scientists often have to rely on the total number of species, the species richness, in a given geographical area just because that is the only information available, or likely to be available in the immediate future. Much work has gone into producing alternative measures. But given the data we already have in scientific literature and museums, the relative ease of putting together inventories of different types of organism, particularly for very large areas, and the fact that it often reflects or incorporates numerous aspects of biodiversity that we’ve already discussed, species richness is not a bad measure. So much of what follows will use biodiversity and species richness almost as interchangeable terms – but not all the time.

There is no one way to write a beginner’s guide to biodiversity. It could take the form of an all-singing, all-dancing panoply of the wonders and beauty of living things. It could be an encyclopaedic catalogue of the variety of living creatures and the places they live. It could focus on how to preserve biodiversity. Or it could combine aspects of all three with different emphases. So, what will be the approach here? It is an old, but I think insightful, idea that the only way you can ever say anything general and all-embracing is by starting with something tangible, specific, familiar, local. For example, over a hundred years ago ‘Darwin’s bulldog’, Thomas Huxley, used the humble crayfish for the title and subject of a book he wrote to introduce interested readers to the general study of zoology. He used aspects of crayfish biology as illustrations, as jumping-off points to explore broader aspects of all animal life. In that same vein, throughout this book I will use the beautiful shores at La Jolla and aspects of my own experience, as a way into some of the big biodiversity issues and patterns. In that respect this is a very personal book.

What will be the key features of this beginner’s guide? In the next chapter we ask: How many species are there currently on Earth and how are they distributed between the different large groupings of organisms we presently recognise? What are these large groupings and how have we ended up with them? This will involve asking another thorny question – what is a species anyway? In Chapter 3 we will see that biodiversity is not distributed evenly across Earth’s surface. There are hotspots and there are coldspots. We will try to visualise the current patterns of biodiversity (or at least measures of that biodiversity), in particular how the number of organisms varies with latitude, altitude and depth. That should take us neatly on to the fourth chapter, where we delve briefly into the origins and development of biodiversity, concentrating particularly on the ups and downs of the past 600 million years. We’ll enter into a debate on the origins of biodiversity that goes to the very centre of what we think about ourselves and the organisms with which we share this planet. Much of our attention will be on extinction, both past and present. We will briefly introduce what looks s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Preface to the second edition

- Preface to the first edition

- 1 The pandemic of wounded biodiversity

- 2 Teeming boisterous life

- 3 Where on Earth is biodiversity?

- 4 A world that was old when we came into it: Diversity, deep time and extinction

- 5 Swept away and changed

- 6 Are the most beautiful things the most useless?

- 7 Our greatest hazard and our only hope?

- 8 No one is too small to make a difference

- Going further: Suggestions for wider reading

- Index