- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

‘It takes courage to be an empathetic leader. And I think if anything the world needs empathetic leadership now, perhaps more than ever.’ Jacinda Ardern

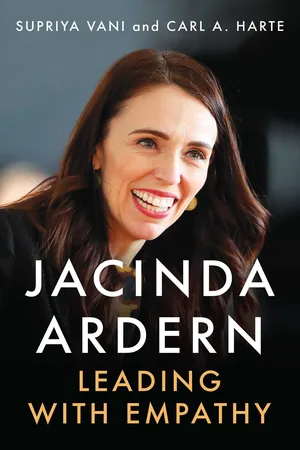

Jacinda Ardern was swept to office in 2017 on a wave of popular enthusiasm dubbed ‘Jacindamania’. In less than three months, she rose from deputy leader of the opposition to New Zealand’s highest office. Her victory seemed heroic. Few in politics would have believed it possible; fewer still would have guessed at her resolve and compassionate leadership, which, in the wake of the horrific Christchurch mosque shootings of March 2019, brought her international acclaim. Since then, her decisive handling of the COVID-19 pandemic has seen her worldwide standing rise to the point where she is now celebrated as a model leader. In 2020 she won an historic, landslide victory and yet, characteristically, chose to govern in coalition with the Green Party.

Jacinda Ardern: Leading with Empathy carefully explores the influences – personal, social, political and emotional – that have shaped Ardern. Peace activist and journalist Supriya Vani and writer Carl A. Harte build their narrative through Vani’s exclusive interviews with Ardern, as well as the prime minister’s public statements and speeches and the words of those who know her. We visit the places, meet the people and understand the events that propelled the daughter of a small-town Mormon policeman to become a committed social democrat, a passionate Labour Party politician and a modern leader admired for her empathy and courage.

Jacinda Ardern was swept to office in 2017 on a wave of popular enthusiasm dubbed ‘Jacindamania’. In less than three months, she rose from deputy leader of the opposition to New Zealand’s highest office. Her victory seemed heroic. Few in politics would have believed it possible; fewer still would have guessed at her resolve and compassionate leadership, which, in the wake of the horrific Christchurch mosque shootings of March 2019, brought her international acclaim. Since then, her decisive handling of the COVID-19 pandemic has seen her worldwide standing rise to the point where she is now celebrated as a model leader. In 2020 she won an historic, landslide victory and yet, characteristically, chose to govern in coalition with the Green Party.

Jacinda Ardern: Leading with Empathy carefully explores the influences – personal, social, political and emotional – that have shaped Ardern. Peace activist and journalist Supriya Vani and writer Carl A. Harte build their narrative through Vani’s exclusive interviews with Ardern, as well as the prime minister’s public statements and speeches and the words of those who know her. We visit the places, meet the people and understand the events that propelled the daughter of a small-town Mormon policeman to become a committed social democrat, a passionate Labour Party politician and a modern leader admired for her empathy and courage.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Jacinda Ardern by Supriya Vani,Carl A. Harte in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

1

Volcanos and Seismic Shifts

Murupara is a small settlement in the North Island of New Zealand, in a remote part of the Bay of Plenty region. It’s a place that feels as if it is drifting, somehow behind in time. Nestled at the edge of the Urewera ranges, near the confluence of the Rangitaiki and Whirinaki rivers, Murupara rests on fault lines: geological, social, cultural, economic. The town divides the pines of the Kaingaroa Forest, planted in the 1920s, and Te Urewera’s unspoiled rainforest – straddling the tame country and the wild, peace and upheaval, Māori and pākehā (European), past and future. The place is a scenic backwater with plentiful trout and deer nearby but fewer prospects otherwise, well past its glory days of the mid-twentieth century.

This was a purpose-built logging town which once had hope and prospects. Now, as with much of the region, Murupara has been left behind by New Zealand’s ‘rock star’ economic centres, Auckland and Wellington. Prosperity departed with the decline of the forestry industry and the rise of mechanised timber harvesting. Among the poorest towns in New Zealand, it is famous for gang violence, the occasional vicious dog attack and the sort of dull, hopeless poverty that seems out of place in a developed country.

Some years ago, a judge declared Murupara a ‘sad, and on occasions, dangerous town’. The numerous derelict houses, with their smashed windows and overgrown lawns, lend a sadness, a sense of poignancy to the place. The homes are mostly old, erected more than fifty years ago, with low gabled roofs, in that mass-produced style of a town built in a hurry. This, one can see, was once a thriving settlement with around double its current population – home to people with decent incomes and purpose, in another era when meaningful work was one’s birthright. In recent decades, this pretty town has endured only with the support of welfare. And not too well, either. According to a University of Otago study conducted a few years ago, Murupara’s community suffers the highest level of deprivation in the country.1

The residents are typical Kiwis: friendly, polite. They are loyal, close-knit and defensive. Somehow, through tourism or some other means, they believe, this town will have its day again, that the ‘gateway to Te Urewera’ may yet profit. Tourism brings hope, mostly for popular hunting and fishing expeditions. A recent indigenous, ‘authentic’ tourism initiative shows some promise. The glory of the town’s natural beauty remains, above economics, beyond the rise and fall of governments and fortunes.

The town’s beauty is itself beguiling, but the land here has its dark secrets. Beneath this green and pleasant countryside, with its mountain peaks and ridges above and its pastures below, lies a sombre reality. The very forces that created this place threaten to destroy it. Murupara was built in the Taupo Volcanic Zone, one of the most active fields of volcanos in the world.

The Taupo Volcanic Zone extends from south of Lake Taupo, which hides the crater of a supervolcano (some sixty kilometres from Murupara), north-eastwards to White Island in the Bay of Plenty. White Island’s volcano is active. It erupted on 9 December 2019, spewing steam and gases, ash and rocks into the atmosphere. Twenty-two people, largely tourists, perished. At a distance of 112 kilometres south-south-west from White Island, Murupara is surrounded by dormant, but by no means extinct, volcanos. The earth’s crust here is thin, as little as sixteen kilometres thick; the rage beneath the surface simmers. The countryside rumbles with almost constant earth tremors.

In a land built on shifting tectonic plates, whose immense natural beauty is shaped by the fire beneath, this town is not so unusual, save for its extremes. In time, its claim to fame may well be its link with the fortieth prime minister of New Zealand, who is Murupara’s most famous daughter.

Jacinda Kate Laurell Ardern was born into a Mormon family in Dinsdale, a western suburb of Hamilton in New Zealand’s North Island, on 26 July 1980. Murupara was her early childhood home, the place where she spent her most formative years.

Aristotle once said, ‘Give me a child until he is seven, and I will show you the man.’ Just the same, give a child a place, a society for the first seven years of her life, and she will be forever impressed, for better or worse, with what she sees, senses and hears there. Murupara, with its exquisite scenery, small-town bonds and sad turns of fate, has left its indelible mark on Jacinda Ardern.

The te reo Māori word murupara means ‘to wipe off mud’ – surely an appropriate metaphor for the rougher side of political life she would encounter decades after she lived here. The Ardern family moved to Murupara when Ross Ardern, Jacinda’s father, took up the post of town police sergeant, and Jacinda started her primary education at Galatea School nearby. For a time, the family lived in a small, grey-brick house in front of the police station.

Jacinda’s mother, Laurell Ardern (née Bottomley), gave up her careers in office administration and teaching – a common decision for so many women of her generation – to support her family. ‘I had a choice of looking after the girls or working, I chose looking after the children,’ Laurell says. But as she explains, with some regret, decisions as to her future, ‘were made by my parents on my behalf . . . [I] would have liked to have attended university as I wanted to be an accountant, but it was not to be’.2 After leaving school, she worked in an office at a service station, and in the Te Aroha post office as a telephonist; she later taught technology for three years in Murupara. As Jacinda and her elder sister Louise grew into teenagers, the only career their mother would have was in their school canteen.

A mother who has taken a very different path, Jacinda is acutely aware of Laurell’s sacrifice. ‘Mum is generous to a fault,’ she said in an interview not long after she was elected. ‘She’s very caring and very kind. She made lots of life choices that were all based on me and my sister.’ Laurell expresses no regret; far from it: ‘I wanted to bring [my daughters] up and put all my time and effort into doing things for them because I knew if I did that, they would be good adults.’3 The results, it has to be said, are self-evident.

Jacinda is grateful to her mother also, for taking an early lead with that most important parental duty: education. Laurell, she says, introduced her and Louise early to words, showing her young girls flash cards of objects around the home, which would help to instil a love of reading as they grew (Jacinda became a great reader of Nancy Drew mysteries and historical non-fiction). Laurell and Ross made sure their girls could read and do simple arithmetic before they went to school. Determined for her daughters to excel, Laurell would place notes of encouragement in their bags, along with their primary school snacks. Before Jacinda entered the world of politics, her efforts had already paid off. Both of her daughters graduated from university, the first in their family to do so.

Naturally, innate character and personality play their part in the Ardern girls’ success. One of the earliest pictures of the future New Zealand prime minister is endearing. Baby Jacinda beams a gorgeous, winning smile, as she does in so many of her later childhood snaps and, indeed, her adult photographs. In her childhood photographs she seems to engage with the camera, in just the way she engages with people – brightly and positively. In photographs from her teens, she is still sporting dark-blonde hair, but the direct, thoughtful gaze that is now famous is evident. In the years since, it has changed little – merely matured.

Laurell says she ‘could have had a dozen Jacindas’, the young girl was so easy to deal with. Her mother recalls that she was ‘different to other children. She was mature beyond her years and had incredible common sense. I don’t really remember her ever getting into mischief because she was so sensible.’4

Sensible and sensitive in equal measure, it seems – qualities that made her acutely aware of the people around her, their feelings and their unhappiness. Though a young girl cannot know the root causes of others’ pain – poverty, conflict, sickness and poor mental health – Jacinda sensed that it wasn’t right for other young children to go without. She questioned why others at her school didn’t have the material comforts she and Louise enjoyed.

Jacinda’s empathy would profoundly influence her, setting in place foundations for her political beliefs and destiny as the social-democrat leader of her nation. While the young Jacinda was in her first years of primary school, in the mid-1980s, tumultuous social and economic change engulfed New Zealand. After more than eight-and-a-half years of National Party government under Prime Minister Robert Muldoon, the Labour Party, led by the charismatic David Lange, won an outright majority in the July 1984 general election. With fifty-six of the ninety-five seats in the unicameral parliament, the country’s fourth Labour government embarked on a programme of economic reforms.

The architect of these reforms was Finance Minister Roger Douglas. A third-generation Labour politician and accountant by training, Douglas was a persuasive speaker, a ruthless political operator. In the late 1970s, he became a convert to Milton Friedman’s free-market theories, and plotted with his colleagues from the opposition benches. When Labour took office, he and his two associate ministers of finance, David Caygill and Richard Prebble – together known as the ‘Treasury Troika’ – immediately set to work, radically restructuring the economy. The reform programme Douglas oversaw in the four years before his sacking in 1988 became notorious. It was dubbed, somewhat derisively, Rogernomics.

Rogernomics was imposed on New Zealand in the manner of a revolution. Unlike in most other democracies, there is no upper house of parliament to provide the necessary checks and balances, nor states and their legislatures to contend with, which might well have tempered the government’s excesses. Neither does the country have the powerful independent think tanks that exist in Britain and the US that could publicly debate government policy. Academics with the temerity to speak out against Rogernomics’ policies found their career paths blocked; journalists were muzzled through their editors. With a party caucus (the Labour members of parliament) ruled by cabinet diktat, Douglas made sweeping changes on many fronts, with little resistance.

In terms of deregulation and implementing free market policies, Rogernomics far surpassed Reaganomics and Thatcherism. From being run, according to Prime Minister David Lange, ‘very similarly to a Polish shipyard’, the country became one of the most deregulated free-market economies of the industrialised world – and this, paradoxically, from a Labour government. With his steely squint and patrician manner more befitting a corporate CEO than man of the people, Roger Douglas became one of New Zealand’s most polarising figures. His programme has been considered alternately a gross betrayal of Labour Party principles and a dose of bitter medicine that the New Zealand economy – reeling under debt, mismanagement and a currency crisis – needed to swallow.

Rogernomics might still divide the pundits, but there’s never been much argument about its impact. Sale of government assets, abolition and amalgamation of government departments and massive redundancies, particularly in the forestry sector, hit New Zealand’s rural population hard. In one horrific week alone, late in March 1987, some 5,000 New Zealand government workers lost their jobs, a significant number in a country with a small population. Years later, an officer with the Social Impact Unit recalled towns full of men trudging from union meetings to register for unemployment benefits, while their women at home wept. The public’s suffering was compounded by the stock market crash of 20 October 1987. Soaring mortgage interest rates touched twenty percent.

Murupara suffered immensely, and just as Jacinda was coming to an age where she could make sense of the world around her. In the turmoil of Rogernomics, the post office, that cherished institution that alongside utility gives rural towns character and a sense of belonging, closed, as did several retail stores. The outlets or offices of the New Zealand Electricity Department, the Bay of Plenty Electric Power Board and New Zealand Railways shut. In just a few years, almost two-thirds of the town’s population was reliant on welfare.

Describing the effects of the forestry redundancies, Murupara’s townspeople later told, with typical Kiwi understatement, how ‘the money dried out’ and ‘the whole town started to turn over – we were losing people’. ‘It was a depressing time,’ one said, ‘because a lot of friends left the town.’5 Like a tree from the immense plantations which sustained it, the town survived, but withered, hollowed out from within.

The young Jacinda was profoundly affected by the human toll of all this. As she told Supriya, ‘I have a lot of early memories not about politics . . . but just simply about observing inequality.’ She heard whispers of suicides – the girl who babysat her and her sister Louise became jaundiced; her skin yellowed with hepatitis C, and she was no longer able to care for them. In her first year of school, Jacinda noticed that unlike her, some child...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Other books by Supriya Vani

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Introduction

- PART ONE

- 1 Volcanos and Seismic Shifts

- 2 A Peaceful Valley

- 3 The Activist Awakes

- 4 Nature and Nurture

- 5 The Mighty Totara

- 6 Family and Politics

- 7 Suffrage and Suffering

- 8 Emerging

- 9 When the Student Is Ready

- 10 Mentor and Role Model

- 11 Resolution

- 12 Overseas Experience

- 13 Baby of the House

- 14 Battle of the Babes

- 15 Catch of a Lifetime

- PART TWO

- 16 Ambition or Ambivalence?

- 17 Turmoil and Teflon John

- 18 Star on the Rise

- 19 For the Party

- 20 Pull Up the Ladder, or the Woman?

- 21 Turning Point

- 22 The Worst Job in Politics

- 23 Woman of Mettle

- 24 Tied to the West Island

- 25 Stardust and Jacindamania

- 26 Victory Day for Winston

- 27 Paddles the Polydactyl Cat

- 28 Mother of the Nation

- 29 Changing the Game, Slowly

- 30 Carving a Path

- 31 Acclaim and the Ides of March

- 32 They Are Us

- 33 Engagement

- 34 Whakaari

- 35 Cometh the Hour, Cometh the Woman

- 36 The COVID Election

- 37 Kindness and the Ardern Effect

- Plate Section

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

- Bibliography

- A Note About the Authors

- Imprint Page