eBook - ePub

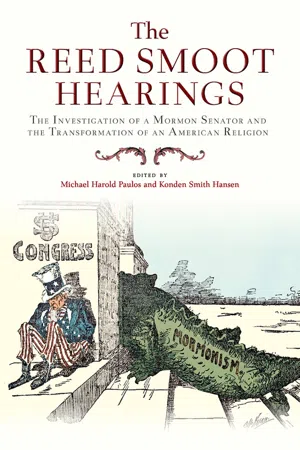

The Reed Smoot Hearings

The Investigation of a Mormon Senator and the Transformation of an American Religion

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Reed Smoot Hearings

The Investigation of a Mormon Senator and the Transformation of an American Religion

About this book

This book examines the hearings that followed Mormon apostle Reed Smoot's 1903 election to the US Senate and the subsequent protests and petitioning efforts from mainstream Christian ministries disputing Smoot's right to serve as a senator. Exploring how religious and political institutions adapted and shapeshifted in response to larger societal and ecclesiastical trends, The Reed Smoot Hearings offers a broader exploration of secularism during the Progressive Era and puts the Smoot hearings in context with the ongoing debate about the constitutional definition of marriage.

The work adds new insights into the role religion and the secular played in the shaping of US political institutions and national policies. Chapters also look at the history of anti-polygamy laws, the persistence of post-1890 plural marriage, the continuation of anti-Mormon sentiment, the intimacies and challenges of religious privatization, the dynamic of federal power on religious reform, and the more intimate role individuals played in effecting these institutional and national developments.

The Smoot hearings stand as an important case study that highlights the paradoxical history of religious liberty in America and the principles of exclusion and coercion that history is predicated on. Framed within a liberal Protestant sensibility, these principles of secular progress mapped out the relationship of religion and the nation-state for the new modern century. The Reed Smoot Hearings will be of significant interest to students and scholars of Mormon, western, American, and religious history.

Publication supported, in part, by Gonzaba Medical Group.

Contributors: Gary James Bergera, John Brumbaugh, Kenneth L. Cannon II, Byron W. Daynes, Kathryn M. Daynes, Kathryn Smoot Egan, D. Michael Quinn

The work adds new insights into the role religion and the secular played in the shaping of US political institutions and national policies. Chapters also look at the history of anti-polygamy laws, the persistence of post-1890 plural marriage, the continuation of anti-Mormon sentiment, the intimacies and challenges of religious privatization, the dynamic of federal power on religious reform, and the more intimate role individuals played in effecting these institutional and national developments.

The Smoot hearings stand as an important case study that highlights the paradoxical history of religious liberty in America and the principles of exclusion and coercion that history is predicated on. Framed within a liberal Protestant sensibility, these principles of secular progress mapped out the relationship of religion and the nation-state for the new modern century. The Reed Smoot Hearings will be of significant interest to students and scholars of Mormon, western, American, and religious history.

Publication supported, in part, by Gonzaba Medical Group.

Contributors: Gary James Bergera, John Brumbaugh, Kenneth L. Cannon II, Byron W. Daynes, Kathryn M. Daynes, Kathryn Smoot Egan, D. Michael Quinn

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Reed Smoot Hearings by Michael Harold Paulos, Konden Smith Hansen, Michael Harold Paulos,Konden Smith Hansen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The National Picture

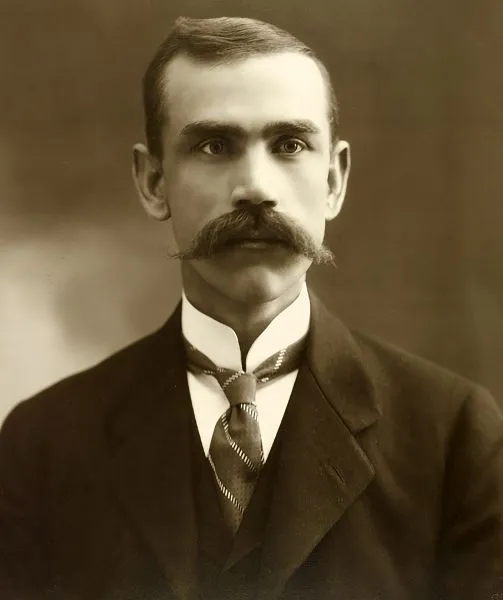

Figure 0.1. Reed Smoot portrait (ca. 1904). Photo courtesy of the Church History Library collection.

Introduction

Konden Smith Hansen

Mormon apostle Reed Smoot’s provocative 1903 Utah election to the United States Senate sparked an intense debate and reconsideration of the relationship between religion and American politics during the “Progressive Era,” a time of heightened cultural, religious, and political transformation. The central question was if America’s political establishment would permit a high-ranking official of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also referenced as the “Mormon Church,” “LDS Church,” “Mormonism,” or just “the Church”), a small religious group deemed outside the mainstream of American ideals, to hold high elective office. Moreover, the disputed aspects of the so-called Smoot Question, as it was colloquially called at the time, were widely publicized in Protestant churches as well as media outlets when formal Senate hearings commenced in Washington from 1904 to 1906. For many religious residents of the Progressive Era, Smoot’s presence in the Senate accelerated the already waning influence of Protestant hegemony within American public institutions. Indeed, the outcome of the hearings in 1907, which resulted in Smoot’s favor, not only indicated an expansion of American religious pluralism but also displayed the continued and complex religious nature of America’s budding secularized nation-state. Conversely, the flexible and accommodating response to the hearings by the LDS Church indicated a fresh openness from Church leadership to pursue a strategy of rapprochement with the country during a time of increased secularization, which in turn granted the Utah Church access to a wider berth of national acceptance.

This olive branch of inclusion extended to the Church was not to be interpreted as a blanket acceptance of religious differences, but rather it was a straightforward and uncompromising declaration that previous iterations of Mormonism would not be tolerated. Only a more secular expression of Mormonism, the one carefully presented by Smoot and his defenders, was acceptable for a seat at the table of full American citizenship. In other words, acceptance of Reed Smoot’s Mormonism into the tapestry of America’s expanding religious plurality, depended upon the Church falling in line with the “progressive” Protestant expectations of this newly emergent secular-modern era.

Often, “the secular” is defined diametrically opposed to “the religious,” inspiring the false oversimplification that a “secular society” is one without religious influence, which has led to a zero-sum perception that distorts how the religious and the secular are considered, along with the dynamic relationship these forces have with American politics. But, as anthropologist Talal Asad explains, the secular is neither a break from nor an evolutionary expansion beyond the religious but rather is a modern expression of it. Notably, the term “secular,” as it has been used in the West, is an idiomatic, mid-nineteenth-century expression that reframes moral progress from “human nature,” as established by the Christian doctrine of the Fall, to that of autonomous human agency. And rather than being a sui generis force that explains a cultural phenomenon, the “secular,” in this context, refers to a specific historical development that plants itself inside a unique American religious environment. In American Protestant thought, the individual was understood to be depraved and in need of the coercive moral power of the righteous state, thereby defining religious liberty via exclusion and suppression. Although unnamed and even denied, this religious influence in American politics denigrated individual liberty, argued David Sehat in his study on religious freedom, and it both established and imposed a narrow version of Protestant moral order on all Americans. Under this structure, and using the influence of ministers and other professors of religion, state actors (often ministers or former ministers) were enabled to prosecute blasphemy, enforce Sabbath day observance, and at times constrain religious belief.1

The end-of-the-century turn toward the secular in America, however, with its new emphasis on human autonomy and individual religious liberty, was likewise rooted in Protestant assumptions, norms, and values. These secularization trends proved crucial to Smoot, since one outcome of these shifts was wider participation in the modern state, regardless of religious belief. William Cavanaugh explained that this so-called secular movement in American politics utilized new terminology that demarcated itself from this earlier ecclesiastical political influence and subordinated this moral establishment to the new secular modern state. Moreover, in Robert Crunden’s study of turn-of-the-century progressive reform, he argues that democratic reformers, even after abandoning explicit expressions of faith, retained and were guided by moral principles taken from their earlier religious training. Religious influence did not disappear within this new secular environment but instead became subtler and implicit. Assessing this nuanced development, Cavanaugh argues that there was nothing new or substantial with this fabricated religious-secular binary, but, rather, the semantic revision created a political myth that expanded the moral authority of a new set of American political elites.2 At its core, the secularization of American politics took shape inside American Protestantism and redefined the theological principle of the human agent as well as the human agent’s relationship to the modern nation-state. For Smoot to carve out a place within this new structure, he would have to do so as an autonomous agent within this Protestant moral worldview, rather than constructing a schematic specific to Mormonism.

In late nineteenth-century America, the term “religion” referred to Protestant Christianity, representing a denominationally diverse tableau that claimed a collective ownership over society and pursued political exclusion on theological grounds. At the same time, the American nation-state, being informed by these secularization trends at the turn of the century, cast political participation in stratums that deemphasized Christian partisanship and the influence of clergy while prioritizing autonomous human agency and the privatization of religious expression. Secularity, then, notes Charles Taylor, means that individuals in society can “engage fully in politics without ever encountering God.” These shifts vibrated across American society and influenced how intellectual, social, political, and religious leaders approached societal issues, giving priority to the tangible and observable over that of the metaphysical. For Taylor, this transition toward secularity was revolutionary, and represented “the first time in history” that “a purely self-sufficient humanism came to be a widely available option”—a schematic whose main goal was that of “human flourishing” with no “allegiance to anything else beyond this flourishing,” including religion.3 As Protestant hegemony and homogeneity over American politics began to recede on account of this wave of secularity, the Smoot hearings similarly questioned Mormonism’s commitment to these same human-focused ideals, regardless of how religiously heterodox the Utah-based Church was to the Protestant establishment. And even though Smoot’s theological worldview and heterodox religious practices were probed throughout the ordeal, these views and performances were not, in the end, disqualifying. What proved most important was Smoot’s ability to define himself as an autonomous moral agent, despite his religious affiliation and ecclesiastical position, which placed himself and his religion squarely within the parameters of the new modern-secular age.

In his exploration of the idea of religious freedom in America, David Sehat notes that religious dissenters were the ones most adversely impacted by the inherent coerciveness of the moral religious establishment, and these dissenters in turn extended the strongest opposition to it. While this establishment remained unnamed and therefore largely invisible to accusations of inappropriate religious influence in American politics, the effort to exclude Smoot based on explicit religious grounds proved unworkable in this new era. Yet despite these ineffectual efforts, Smoot’s victory in 1907 was by no means assured, as federal protections of unorthodox religious belief or nonbelief had not been fully established, nor had the First Amendment been applied to all levels of government. In this context, the Smoot hearings stand as a case study that highlights the awkward restrictions of religious liberty in America, based on principles of exclusion and coercion, and it opened to public gaze the inconsistencies these principles posed for a new century of secular progress. Although still powerful in 1907, it became c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Part I: The National Picture

- Part II: The Local Picture

- Appendix: LDS Officials Involved with New Plural Marriages from September 1890 to February 1907

- Contributors

- Index