- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

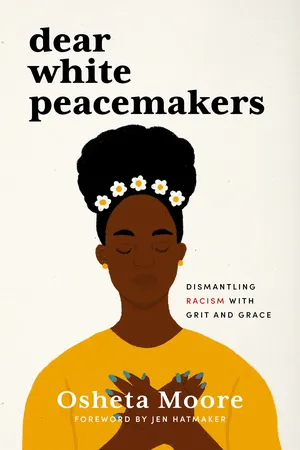

Dear White Peacemakers is a breakup letter to division, a love letter to God’s beloved community, and an eviction notice to the violent powers that have sustained racism for centuries.

Race is one of the hardest topics to discuss in America. Many white Christians avoid talking about it altogether. But a commitment to peacemaking requires white people to step out of their comfort and privilege and into the work of anti-racism. Dear White Peacemakers is an invitation to white Christians to come to the table and join this hard work and holy calling. Rooted in the life, ministry, and teachings of Jesus, this book is a challenging call to transform white shame, fragility, saviorism, and privilege, in order to work together to build the Beloved Community as anti-racism peacemakers.

Written in the wake of George Floyd’s death, Dear White Peacemakers draws on the Sermon on the Mount, Spirituals, and personal stories from author Osheta Moore’s work as a pastor in St. Paul, Minnesota. Enter into this story of shalom and join in the urgent work of anti-racism peacemaking.

Race is one of the hardest topics to discuss in America. Many white Christians avoid talking about it altogether. But a commitment to peacemaking requires white people to step out of their comfort and privilege and into the work of anti-racism. Dear White Peacemakers is an invitation to white Christians to come to the table and join this hard work and holy calling. Rooted in the life, ministry, and teachings of Jesus, this book is a challenging call to transform white shame, fragility, saviorism, and privilege, in order to work together to build the Beloved Community as anti-racism peacemakers.

Written in the wake of George Floyd’s death, Dear White Peacemakers draws on the Sermon on the Mount, Spirituals, and personal stories from author Osheta Moore’s work as a pastor in St. Paul, Minnesota. Enter into this story of shalom and join in the urgent work of anti-racism peacemaking.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dear White Peacemakers by Osheta Moore in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

Wade in the Water

1

God’s Gonna Trouble the Water

Fleeing White Supremacy

I once heard a story about Harriet Tubman that I’m sure is exaggerated and therefore mythologized. Quite often in the retelling of their stories our favorite heroes move from ordinary people who were brave enough to show up in extraordinary circumstances to superhuman dissidents the likes of which we’ll never be. This story is about one of Harriet Tubman’s trips to lead a group of enslaved people to the North. After a few days of traveling, they heard hounds baying and in pursuit, so they moved their caravan to the river, where they hid for several days, slowly trudging in the water, taking rests when they could, keeping an ear out for the barking of the dogs and the galloping of the slave patrol horses. They were hungry, thirsty, sore, and cold. The mothers did their best to quietly comfort whiny children. The group was tense—anxious as they made their way to freedom, exhausted from the hard journey. “Wade in the Water,” they knew, told them to stay in the water so as to confuse the bloodhounds used to track them—but singing something on the plantation while you harvest and process the cotton and actually living it are two very different things.

Wading is messy. Wading is dangerous. Wading is confusing. Wading often makes you long for the solid ground of the plantation—at least that’s a discomfort you’re used to. One man stopped abruptly and the procession behind him stuttered to a halt. Some of his fellow journeyers fell into the water, making a dangerously loud splash. Harriet whipped around and glared at the man. “Hush now,” she hissed. The man, dripping with water and rage, walked up to Harriet and announced he was leaving the group. He was done. He would go back to the plantation and throw himself at the mercy of the master, and whatever fate would become him had to be better than this hard slog to the “promised land.” Harriet looked around at the group and knew that if this man went back, if he got out of the water and alerted the men searching for them of his presence, the whole group, herself included, would be done for. The story goes on to say, Harriet pulled a gun from the pocket of her skirts, pointed it squarely at the man’s forehead, and said, “You have a choice, then: die now or keep walking. We’re getting to freedom and you will not stop us.” Harriet cocked her weapon and waited. The others in the group began to whisper their pleas for him to stay—some appealed to his sense of self-preservation, “You don’t want to die,” some reminded him of the ways the overseers beat him mercilessly, some begged him to not cause a ruckus and get them all caught. Harriet stood quiet and resolved, revolver ready. The man looked around and realized that suffering together for the sake of freedom was far better than dying in that river, so he held his hands up, apologized to Harriet Tubman, his Moses from the oppression of the plantation, and got back in line, wading in the water—even though it cost him his comfort and even though he had very little hope for the journey.

Dear White Peacemaker, in a lot of ways, you’re like the exhausted and discouraged man. You’ve looked around and seen how we cannot ignore race anymore. It’s no longer enough to be polite, you’ve got to be proactive, and so you’ve left the plantation of white supremacy! You’re making your way out of that mindset—however, when you run into trouble (when, not if), you’re tempted to give up, to chalk up your zeal for freedom as a phase. Like the man, you want to turn back—you’re unsure why you even left to begin with. He lacked vision for life without the oppression of white supremacy, and sometimes, White Peacemaker, you do too—even though it’s keeping you sick, it’s a sickness you’re comfortable with.

I worry, friend, that you’re building a legalistic practice of “read this, say this, protest here,” which is always shame-laden and hustle-bound. Belovedness, however, undoes our striving and proving, and if there is one thing white supremacy reinforces, it is a scarcity mindset of identity and worth. This is partly why you’re exhausted, my friend. You’re constantly proving your worth and unsure how to measure your efficacy. Instead, the only thing you should be focused on is owning your Belovedness, proclaiming my Belovedness, and working to become the Beloved Community.

In part 1 of this book, we’re going to look at one of the chief dangers of white supremacy culture: how it systematically and subtly strips you of your God-given Belovedness and its gracious lens of your identity—because before we can get to the kingdom ethics of the Sermon on the Mount, we need to wade in the water where we are baptized Belovedness.

2

Your Name Is Not Racist, It’s Beloved

One Friday, two years ago, I sat by a lake at sunset deeply troubled. Goldenrod, purple, and crimson rays reflected across the lake’s still surface. For a split second I wondered if I should capture it with my phone. Maybe save it for a day when my life seemed anything but radiant and still so I could post it to social media with some calming quote, poem, or if on that day I wanted the world to believe I’m pious, a Scripture passage.

I wasn’t still (or particularly pious even) by that Georgia lake, because violence was brewing in my belly. It was circling in my mind. Animating my fingers as they thrummed on my tree log bench. I wanted to unleash it. I wanted to contain it. I wanted it to empower me because I felt so incredibly powerless.

I was on a seven-day trip with a group of White people who wanted to know why.

Why is the church tackling such a divisive issue as race, one that surely brings more conflict than peace?

Why is our country so bound up in this cycle of uncivility?

Why are Black people so angry all the time?

Why is this even my problem? I’m White.

Why don’t communities of color trust the police?

Why. Why. Why. Why.

That whole week I fielded questions and walked alongside them through civil rights museums and southern courthouses. We learned how almost everything in our world—education, housing, policing, media, laws, and even the church—has been influenced by the violence of white supremacy.

And the whole time I wondered, “When we get back home, will you still care? When you’re no longer standing under concrete slabs with the names of lynched Black people, will you still care? When we’re not standing in front of a wall of jarred dirt, all from places where the blood of innocent Black citizens seeped into the ground after White hands beat, shot, or stabbed them, will you still care?” We learned that sometimes, these extrajudicial executions happened on front lawns of churches with the pastor nursing a tall glass of lemonade while his parishioners bent their knees to the gods of scarcity and hate. I looked at this group of White Christian men and women and wondered, “How does this knowledge affect your commitment to Jesus, a man who suffered his own brutal and excruciating extrajudicial execution? Does it at all?”

Spending days gazing at our horrific past made me angry at White people in a way I never thought possible. All those pictures of White people committing various acts of violence toward people of color did the thing I feared it would—I began to hate them. White supremacy’s violence was getting inside of me.

I wanted to serve them just a teaspoon of the gallons of internalized hate this world has force-fed me.

I wanted my anger to exact some form of vengeance—so very badly.

I wanted every White person on the trip to suffer—and while I couldn’t enact on their pale bodies the kinds of things my ancestors endured, I could use the only power I had—I was their leader. Their teacher. The person entrusted with their anti-racism training for that week. And because this was a group of progressive-ish Christians: I could make them feel so incredibly bad. I could wield my moral authority as the Black leader in the group. I could manipulate them with shame and anger.

I knew how to do it, too. The next day we were going to have an extended check-in. I could prepare a discussion time that would make them feel the weight of the shame of their White skin. I could sneer “privilege” like an accusation and proclaim them “fragile” as if it were a death sentence. I would tell them my hard stories, my painful experiences with White people, and then expect them to atone for the collective sins of all White people. Repent for their aggressions, own their mistakes. White sin-eaters . . . that is what I could make them into. And they, wanting to be “woke,” wanting to not seem like racists, wanting to be the ally and not the problem, would take it. They would take in my violence.

A fish leaped from the water and snapped at the fly hovering right above the surface, sinking back into the lake, her belly a little fuller. There’s something nourishing about violence, I thought—even if just for a moment.

I was in danger of a kind of just war theory–approach to anti-racism that says I get to use violence in thought, word, and even deed toward White people to accomplish my end goal of a world free of violence to Black and Brown bodies. It did not sit well with me as I sat by the lake. This group trusted me to be a faithful shepherd primarily because of my commitment to Jesus the Good Shepherd.

In my heart, they were not my siblings, they were just beyond empathy because of their White skin—somehow on that justice journey, they became my enemy.

As the sun set and the moon came more clearly into view, I decided to sit with my violent impulses until the stars came out. “Only in darkness can you see the stars,” said Dr. Martin Luther King in the last speech he would give before his assassination. I thought with a chuckle, “Where are the stars when the darkness is within you?”

I texted a friend before heading back to the group to call it a night and wrestle with my violence in my tent. “It’s like the violence I’ve seen our people suffer has gotten on the inside of me,” I wrote. “Pray for me. I want to love these White people, but I’m not sure I’ve got it in me anymore.”

My friend, a gorgeous Black woman who specifically prayed for me to not be derailed from my calling to teach that group peacemaking alongside anti-racism, texted back, “I’ve got you, Sis.” With a heart emoji and a star. She also sent a gif of Whitney Houston from the musical Cinderella because she loves me and knows fairy godmother Whitney makes everything better.

The last day of the trip was a Saturday morning, and we were all wrung out. Spent from being too close to each other in a fifteen-passenger van, pulling into campgrounds to set up after a day full of learning, processing, grieving, dialoguing about race in our country. The small joys we had were a comedy playlist from Spotify and meal breaks where we stretched our legs and made sandwiches from the coolers in the back of the van.

My small joys were a Frappuccino and white powdered donuts that I balanced in my hands while adjusting my hat that said “Nah. Rosa Parks 1955”—my own pre-trip passive aggressive purchase to fortify me for the journey. I remember the day I bought it, y’all . . . it’s true, when it came, I danced around my house and ran to show it to my husband, a White man listening to The Roots while he worked on his sermon at our dining table.

“Look! Look! It’s here!” I waved the heather gray baseball cap in the air and ceremoniously placed it on my head. “Isn’t it the best?”

T. C. rested his headphones on his neck and squinted to read the writing on my hat.

“Nah. Rosa Parks 1955.” He smirked and nodded. “Clever. So that’s the hat you’re going to wear on the trip?”

He knew I was worried about my hair over seven days of traveling, camping (especially in the inclement weather forecasted), and walking around in the South with all its curly hair–challenging humidity, so I told him I needed a really cute baseball cap to accessorize the puffy ponytail I was sure to have by day two.

“Yeah. It’s perfect because it’s exactly how I’m feeling about these White people. Nah. I’m not going to overextend myself on this trip. Nah . . . I’m not going to pull punches about how terrible racism is in our country and how they don’t get to be complicit about it anymore. Nah . . . White people! Nah. I’m going to push them every single waking moment. We don’t have time to play anymore, babes! Black children are dying over toy guns and loud music.” I put the hat on my head and did my best Janet Jackson “What Have You Done for Me Lately” head wobble. Nah. This Black woman was done.

I was adjusting my hat to block the sun when I noticed Aimee out of the corner of my eye. She was slumped against the side of the gas station, her phone clutched in her hand. She was more than exhausted, she was devastated. My first thought was, “Good. She looks in this moment how I feel every single day.” I started to move toward the van when I remembered a line from a song I love that says we’re all stardust, walking constellations on this Earthen land.

I looked at Aimee, and as clear as I have ever sensed God’s conviction, I felt the Spirit say, “She is my Beloved and she doesn’t feel like it. This week has made her question her Belovedness as a White person.”

Stars in the darkness. “Here’s where the stars are,” I thought, remembering my prayer by the lake.

I walked over to Aimee and put my precious snacks on that hot concrete and wrapped my arms around her.

Aimee wrapped her arms around me almost instantaneously, melting into and clinging to me, as I cooed in her ear, “Shh . . . it’s okay . . . You’re going to be okay . . . We’re going to be okay . . .”

My friend Sarah asks every morning, “God, how do you want to mother me?” and as I hugged Aimee I asked God a similar question. “Mother God, how can I care for your Beloved daughter today?”

Just love her and allow yourself to be unguarded.

So that’s what I did. I hugged her for as long as she needed and let myself receive her White tears. I chose to love her by being present in her pain even though I’m told Black women who give their maternal instincts to White women are playi...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Foreword by Jen Hatmaker

- Preface: Markers on My Hand, a Call to Empathy

- Come to the Table

- Part I: Wade in the Water

- Part II: There is a Balm in Gilead

- Part III: Down by the Riverside

- Part IV: Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn me Around

- Epilogue: By the Waters of Bde Maka Ska

- Note to the Reader

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

- The Author