- 412 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

This book, first published in 1999, addresses Beckett's visual and musical sensibilities, and examines his visionary use of such diverse modes of creative expression as stage, radio, television and film, when his medium was the written word. The first section of the book focuses on music; the second part analyses the visual arts; and the third part examines film, radio and television. This book uncovers aspects of his thinking on, and use of the arts that have been little studied, including the nonfigurative function of music and art in Beckett's work; the 'collaborations' undertaken by composers, painters and choreographers with his texts; the relation of his literary to his visual and musical artistry; and his use of film, radio and television as innovative means and celebration of artistic process.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part I

Chapter 1

Words and Music: Situating Beckett

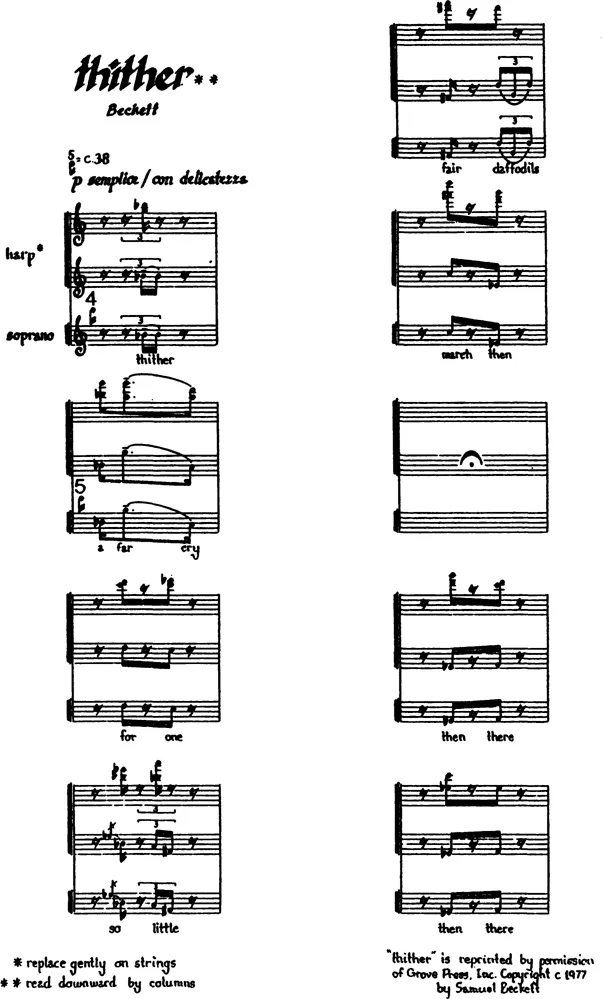

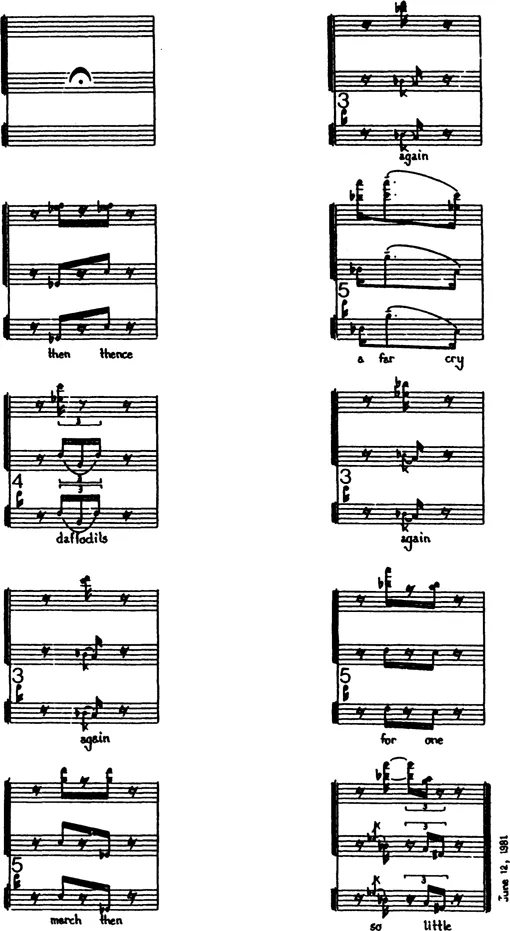

“thither” for soprano and harp is part of a song cycle entitled Now and Then. *The formal design of the poem is reflected in the focal line of the music which also finds its echo in the harp’s doublings.The music is notated in vertical columns, rather than horizontally, to reflect the visual design of the poem. Pauses and silences are dictated by the spacing of the lines. Overlappings and repetitions of single words gently insist on images of innocence, vulnerability and the ominous threat of annihilation.Words, voice and harp all merge into one—each accompany each other.

Chapter 2

Samuel Beckett and the Arts of Time: Painting, Music, Narrative

Beckett, Time, and Narrative

So up then in the grey of dawn, very weak and shaky after an atrocious night little dreaming what lay in store, out and off.... But I was hardly down the stairs and out into the air when the stick fell from my hand and I just sank to my knees to the ground and then forward on my face, a most extraordinary thing, and then after a little over on my back, I could never lie on my face for any length of time, much as I loved it, it made me feel sick, and lay there, half an hour perhaps, with my arms along my sides and the palms of my hands against the pebbles and my eyes wide open straying over the sky.8

Now is there nothing to add to this day with the white horse and the white mother in the window, please read again my descriptions of these, before I go on to some other day at a later time, nothing to add before I move on in time ski...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Series Editor’s Foreword

- Editor’s Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Contributors