eBook - ePub

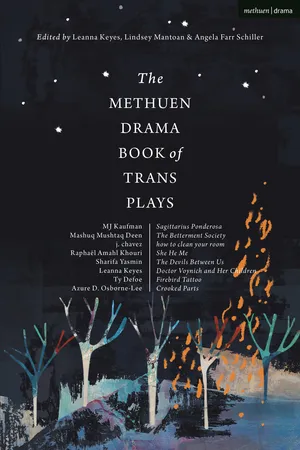

The Methuen Drama Book of Trans Plays

Sagittarius Ponderosa; The Betterment Society; how to clean your room; She He Me; The Devils Between Us; Doctor Voynich and Her Children; Firebird Tattoo; Crooked Parts

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Methuen Drama Book of Trans Plays

Sagittarius Ponderosa; The Betterment Society; how to clean your room; She He Me; The Devils Between Us; Doctor Voynich and Her Children; Firebird Tattoo; Crooked Parts

About this book

Finalist in the 2022 Lambda Literary Awards for the LGBTQ Anthology category

The Methuen Drama Book of Trans Plays for the Stage is the first play anthology to offer eight new plays by trans playwrights featuring trans characters.

This edited collection establishes a canon of contemporary American trans theatre which represents a variety of performance modes and genres. From groundbreaking new work from across America's stages to unpublished work by new voices, these plays address themes such as gender identity and expression to racial and religious attitudes toward love and sex.

Edited by Lindsey Mantoan, Angela Farr Schiller and Leanna Keyes, the plays selected explicitly call for trans characters as central protagonists in order to promote opportunities for trans performers, making this an original and necessary publication for both practical use and academic study.

Sagittarius Ponderosa by MJ Kaufman

The Betterment Society by Mashuq Mushtaq Deen

how to clean your room by j. chavez

She He Me by Raphaël Amahl Khouri

The Devils Between Us by Sharifa Yasmin

Doctor Voynich and Her Children by Leanna Keyes

Firebird Tattoo by Ty Defoe

Crooked Parts by Azure Osborne-Lee

The Methuen Drama Book of Trans Plays for the Stage is the first play anthology to offer eight new plays by trans playwrights featuring trans characters.

This edited collection establishes a canon of contemporary American trans theatre which represents a variety of performance modes and genres. From groundbreaking new work from across America's stages to unpublished work by new voices, these plays address themes such as gender identity and expression to racial and religious attitudes toward love and sex.

Edited by Lindsey Mantoan, Angela Farr Schiller and Leanna Keyes, the plays selected explicitly call for trans characters as central protagonists in order to promote opportunities for trans performers, making this an original and necessary publication for both practical use and academic study.

Sagittarius Ponderosa by MJ Kaufman

The Betterment Society by Mashuq Mushtaq Deen

how to clean your room by j. chavez

She He Me by Raphaël Amahl Khouri

The Devils Between Us by Sharifa Yasmin

Doctor Voynich and Her Children by Leanna Keyes

Firebird Tattoo by Ty Defoe

Crooked Parts by Azure Osborne-Lee

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

Disembodied Articulations

Waiting, Watching, and Witnessing as Queer Praxis in Sagittarius Ponderosa

Jesse D. O’Rear

Sagittarius Ponderosa is a play about transition.

In the inaugural issue of Transgender Studies Quarterly, Julian Carter writes the following in their contributed essay on the word “Transition”:

‘Transition’ differs from ‘sex change’ in its inherent reference to duration rather than event, from ‘assuming a dress’ in its attention to the embodied self who dresses, and from ‘coming out’ in its disengagement from politically radical and street subcultures; yet conceptual residue from these earlier vocabularies adheres to the term as the activities it encompasses expand. […] Transitions are brave work. Like birth, like writing, gender transition is when hopes take material form and in doing so take on a life of their own.

(Carter 2014: 235–236)

Essentially, what Carter identifies in this passage is that “transition” as a term in application to trans subjects rejects a linear chronological progression. To “transition” is not to move from one point to the next, nor to make a singular change to one’s wardrobe or expression, nor to make an announcement that changes one’s identity or the way one is perceived in public. Subsequently, Carter acknowledges that “transition” does not encompass a singular set of actions. By pluralizing the term in their essay, Carter highlights that there is no singular definition of what it means to “transition.”

At the crux of Sagittarius Ponderosa is this: “Transitions are brave work.”

Sagittarius Ponderosa focuses on a family in the midst of a collective transition, within which each member experiences their own individual transition(s) over the course of the script. To center the play around transitions requires that we remember that transitions are moments of movement, not fixed points in time. Where this play finds its tension and its growth are in the characters’ resistance to, and eventual embrace of, “duration rather than event.”

Sagittarius Ponderosa asks—and requires—us to consider the stillness of transition. As José Esteban Muñoz states in his 2009 book Cruising Utopia, “waiting” is an action to the marginalized: “Those who wait are those of us who are out of time in at least two ways. We have been cast out of straight time’s rhythm, and we have made worlds in our temporal and spatial configurations” (p. 182). “Time” for queer subjects is something that we know we are not guaranteed, constantly in a state of either fighting to acquire or keep our legal rights and our dignities in an actively queerphobic/racist/classist/colonial/imperialist society. Additionally, and relatedly, due to the very legal and social discriminations and economic hurdles faced by queer and trans people in the U.S., we also face a shortage of time in our lifespans. Lack of adequate healthcare, as well as our community’s relationship to the onset of and continuing HIV epidemic, leaves few of us with the ability to view “time” as something of which we have an abundance.

Contrary to “straight time’s rhythm,” “queer time” exists in opposition to the measurement and passage of time which Elizabeth Freeman (2010) deems “chrononormativity” in its service to capitalist colonial and patriarchal hegemony. Similarly, Jack Halberstam’s In a Queer Time and Place (2005) theorizes “queer time” in relation to risk and failure as queer modes of living in the face of the productive body endorsed by capitalism.

Chrononormativity expects the movement of transition but toward a purpose that reinforces and supplements capitalism—and, consequently, racist patriarchal heteronormativity, all of which are inextricably tied to it. Bound up in and reiterated by notions of “the American dream,” chrononormativity seeks to create seekers and generators of capital, as opposed to interdependent community members, out of its participants. This expectation seeps into every crevice of our indoctrination into capitalism, even into our understandings of health and wellness. As Halberstam explains, “in Western cultures, we chart the emergence of the adult from the dangerous and unruly period of adolescence as a desired process of maturation; and we create longevity as the most desirable future, applaud the pursuit of long life (under any circumstances), and pathologize modes of living that show little or no concern for longevity” (2005: 4). As such, physical and mental maturity is linked to a reduction in behavior considered to involve risk—whether that be physical, social, or economic risk. More so than a concern over health and well-being, chrononormative longevity aims to ensure an enduring and docile population of laborers and consumers.

The transitions in Sagittarius Ponderosa guarantee no such thing. The story follows a genderqueer main character, Archer/Angela, who returns to live with his parents at age twenty-nine after a span of time spent living elsewhere. Archer’s Mom is a housewife with dreams of being a gardener, though much of her time is spent tending to Archer’s father (Pops) as he battles an unnamed health condition related to his love of processed sugar. Grandma, Pops’s mother and a widow, lives in her own house nearby, hard of hearing and desperately dreaming that Archer, who she still perceives as her granddaughter, will soon get married. Every character is fueled by a relationship to the passage of time: resistance to, longing for, rejection of, fear toward what may be ahead, behind, or right in front of them.

Each of the interior spaces—Mom, Pops, and Archer’s house and Grandma’s next door—exist as part of the Ponderosa Forest. One eponymous Ponderosa, under which Archer and his love interest Owen spend their time together, is also present on stage. According to the script, regarding the Ponderosa: “She never goes away” (p. 18).

In fact, as Owen points out, the Ponderosa lives and ages in spite of the capitalist death drive while also in danger because of it. Owen, Archer’s paramour and a Ph.D. student, is learning about and trying to reinstate prescribed burning, a process of forest fire prevention practiced by the Northern Paiute on whose land the forest—and the play itself—is set. Owen himself claims some Native ancestry, and laments not being more connected with that part of his heritage. Without that practice, coupled with the devastating effects of global environmental destruction, the Ponderosas cannot continue to thrive—or, eventually, even survive.

Prescribed burning, as Owen describes, helped to “keep the trees healthy and the forest sparse” so that naturally occurring wildfires, inevitable in the summer heat, would not destroy the entire forest (p. 40). It was a process of preparing for what was inevitable in nature; a moment of transition through loss to prevent a transition to extinction.

But Owen reminds us: “[Now] we don’t do that and that’s why there’re so many less of the trees” (p. 40). Colonizers, in their theft of the land, prohibited the vital tending of the land by its human communities. The advancement of industrialism and capitalism-fueled globalization destroys the land and increases the temperature of the earth, the phenomenon known passively as “climate change.” As a result, the forest dwindles. A 400-year-old tree faces extinction because of the egomaniacal greed of murderous settlers who arrived 200 human years into this Ponderosa’s life.

Owen also points out to Archer that the Ponderosa experiences time differently than humans: “A year for us is like an hour for them, you know?” (p. 21). And for the characters in Sagittarius Ponderosa, time seems as if it is passing so quickly. In the span of the single play, the characters experience a year of loss, grief, love, and joy. The audience is, in many ways, like the Ponderosa. We experience in one hour of our own time an entire year’s worth of life on stage.

The Ponderosa stands on stage as a reminder of the subjective passage of time. What occurs under her boughs are but a blink of an eye to the tree. For Archer and Owen, it feels that way, too, but for different reasons: Owen will leave soon, returning to school, and Archer has just arrived, to be in the forest indefinitely as this part of his life demands.

The Ponderosa never leaves. She remains on stage for the entirety of the production. She has been in that forest for at least, according to Owen’s best guess, 400 years. She will (hopefully) continue to be in that forest long after Pops, Grandma, Mom, and even Archer’s lifespan ceases. She waits, and has waited, and will wait. She watches, has watched, and will watch. She witnesses, has witnessed, and will witness. The Ponderosa is the queerest character in the play.

What is transition to a being like the Ponderosa pine? How does the Ponderosa ask us to reconsider our own relationships to time, to the cycles of life, to our expectations of ourselves and of each other? Grandma expects that Archer will soon be married, because that is what she expects of women at Archer’s age. Yet she, herself, is left husbandless at her age due to the life cycle of death. Her own son makes the transition from life to death before she does, disrupting the expected cycle that a child will bury his mother, not the other way around.

What is the human cycle of life and death to the Ponderosa pine? What is the capitalist timeline of life, the slow march toward death during which we are expected to hit markers of productivity and success as defined by our accumulation of capital, to the Ponderosa pine? What is chrononormativity to the Ponderosa, other than a weapon used in the continual destruction of herself, her family, and her home?

Likewise, what are these concepts to trans people? What is the transition from adolescence to adulthood when some of us will experience the effects of puberty twice: once against our will when we are young and a second time with our consent when we are older? And whether or not we choose to pursue transition by medical means, how are we served by a narrative of maturity equivalent to a reduction in risk when simply being trans in a transphobic culture is risky behavior?

Every one of us, of all genders and sexes, transitions through multiple phases and stages of our lives. Our identities and expressions of our selves shift constantly, even sometimes within a day, depending on the context in which we find ourselves in every moment. Gender-related transitions have garnered attention for the grand physical changes that often accompany or characterize these particular shifts in identity and expression. Yet trans people are not the only people who make changes—to our names, our bodies, or our expressions of our selves. And we are not the only ones who scoff in the face of chrononormativity.

The same can be said of each member of Archer’s family. They are all waiting in and for transition. Waiting for death, waiting for (re)birth, waiting for love, waiting for salvation, waiting to find something: the self, the past, the future, each other. And these moments of waiting are moments of transition—in the sense that moments of transition are also always moments of waiting.

The structure of the nuclear family attempting to stagger their way through a series of tumultuous transitions hearkens to another “trans play:” Taylor Mac’s 2014 script Hir. Much like Sagittarius Ponderosa, Hir focuses on a main character who returns to his family’s home to find it the site of numerous transitions. However, Hir places as its central character a member of the hegemonic class: white, cisgender, heterosexual, military veteran Isaac. When he arrives, the house is disorganized and dirty. His father, formerly emotionally and physically abusive to all members of his family, is dressed in clownish drag and is kept silent and perpetually confused by the effects of a stroke and a cocktail of drugs which Isaac’s mother feeds him every day.

The play’s trans-identified character is Isaac’s brother, Max, who he previously thought to be his sister. Max uses gender neutral pronouns (ze/hir) and takes testosterone. It seems as though Max’s gender transition and subsequent political radicalization is the catalyst for hir mother’s transition from passive wife and victim of domestic abuse to how we see her in the play: the home’s powerful matriarch, depicted as delusionally delighting in acts of physical, emotional, and social retribution against her abuser.

While Hir uses gender transition as the gateway to explore a world that is confusing and unsettling to a member of the hegemonic class (Isaac: white, cisgender, heterosexual, participant in U.S. imperialism), in many ways, Sagittarius Ponderosa decenters Archer’s transness. Archer transitions in other ways—back to his parents’ home, into being a fatherless adult, between employment opportunities—but he begins and ends the play in the same position with regard to his gender. There are no conversations about Archer’s gender identity or status with regard to transition.

Pops begins the play in a moment of transition, moving from a diet heavy in processed sugar to something less sweet. Very quickly into the play, he transitions from Robert to Robert Jason, at his doctor’s behest, to help grapple with the chronic illness in his body. His wife attempts to keep him on a strict schedule, also at his doctor’s behest, with a dictated sleep schedule, which Robert Jason frequently rejects. Then, he embarks on the transition from life through death. In transitioning through death, he takes on new life as Peterson, his mother’s late-in-life companion.

Archer resists the transitions of the culture in which he has been raised. By identifying himself through astrology, he rejects the Gregorian calendar: “I’m also grateful for my name. And for it being the month I was born in. […] I mean the astrological month. Sagittarius time” (pp. 19–20).

Sagittarius is the most mature of the fire signs. He is the Archer, the Hunter, the Explorer. Sagittarius energy brings with it the urge to travel, the yearning to seek and find things outside of one’s comfort zone. Sagittarians do not fare well when asked to stay put.

But rather than an arrow, the symbol of the constellation, Archer is more like a boomerang: he leaves home, then returns. The American cycle of adulthood expects that with maturity comes leaving the family home. Returning to the nest has become a critique slung at the millennial generation, an implication that we are unfit for the trials and tribulations of being a “grown-up” in “the real world.” Archer also defies what could be considered a normative narrative of queerness: the young queer adult who leaves their hometown to find community in a chosen family of other queers in a new but exciting atmosphere.

Archer does not explain why he has returned home. He references “family stuff” to Owen, and we can infer that this has to do with his father being unwell. But there is tension within the house around such things: in their final conversation, Pops accuses Archer of being part of the “police state” for refusing to drive to the store for some candy in the middle of the night; and after Pops’ death, during one of their arguments Archer accuses Mom of wishing that he would move out. And Archer’s attitude at the beginning of play does not inspire much confidence that moving home was a choice made of his own free will.

Grandma yearns for Archer to fulfill chrononormative ideals. Grandma’s concerns come from a place of love—she wants Archer to be married because she does not want him to be alone. But she is unable—or unwilling—to envision him as queer, trans, and happily partnered. Her worldview only encompasses what she understands as t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Biographies

- Play Synopses

- Introduction: In a Trans Time and Space

- Part One: Disembodied Articulations

- Waiting, Watching, and Witnessing as Queer Praxis in Sagittarius Ponderosa

- Sagittarius Ponderosa

- Generations of Language: Mashuq Mushtaq Deen in Conversation with Stephanie Hsu

- The Betterment Society

- how to tell time (when you are trans and processing trauma)

- how to clean your room (and remember all your trauma)

- Part Two: Fraught Spaces

- Witnessing the Revolutionary Mundane: Raphaël Amahl Khouri’s Queer Documentary Theatre

- She He Me

- “Challenging Every Memory”: Manifesting Futurity in The Devils Between Us

- The Devils Between Us

- Part Three: Familiar/Familial

- Cruising Dystopia

- Doctor Voynich and Her Children

- Transcending Gender to “Soar Above the Earth” in Ty Defoe’s Firebird Tattoo

- Firebird Tattoo

- All In and Out of the Family: A Critical Introduction to Azure Osborne-Lee’s Crooked Parts

- Crooked Parts

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Methuen Drama Book of Trans Plays by Azure D. Osborne-Lee,Ty Defoe,MJ Kaufman,Raphaël Amahl Khouri,J. Chavez,Sharifa Yasmin,Mashuq Mushtaq Deen,Sharifa Yazmeen, Leanna Keyes,Lindsey Mantoan,Angela Farr Schiller, Leanna Keyes, Lindsey Mantoan, Angela Farr Schiller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre Playwriting. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.