![]() Part I. THE PRACTICE

Part I. THE PRACTICE![]()

1 Health Workers and Smoking

Fabio Lugoboni 1

1 Department of Internal Medicine, Medical Unit for Addictive Disorders, University of Verona, Policlinico GB Rossi, Verona, Italy

The most dangerous drug from a social point of view? Alcohol. The most damaging for the single person? Heroin. But the most lethal substance, in that it contributes to the highest number of deaths? Undoubtedly tobacco smoking, responsible in the world for one death every 10 seconds. Every smoker, if he doesn’t quit, will have 14 years of his life taken away from him.

"Indeed it is difficult to identify any other condition that presents such a mix of lethality, prevalence and neglect despite effective and readily available interventions." These words are the first lines of the American guidelines for the treatment of smoking addiction.

In Italy the percentage of doctors who smoke varies: in a study carried out a few years ago on 938 pneumologists, 26.5% were smokers. Male doctors smoke as much as other graduates, following the trend described for the level of education; whereas female graduates in medicine smoke more than other graduates, as shown by the figure of 42% found in a study among female graduates in medicine in southern Italy. In other words, being a doctor does not offer any protection against smoking; on the contrary, being a doctor and a woman appears to be a risk factor.

Prevention and educational campaigns are important. One should, however, remember that in the United States, a country known for its 30-year fight against smoking, 23% of the adult population are still smokers; and also that among youngsters the percentage of smokers is above 20%. These data once again suggest that prohibition is not a valid method to solve problems tied to addiction to psychoactive substances. It is more useful to aim at widespread information and accessibility to treatment though respecting the rights of both smokers and nonsmokers.

It is time to ask you an important, but not fundamental question: Do you smoke?

The USA, which has made the fight against smoking a priority health objective, is a country where only 2% of doctors smoke, the same prevalence as found in the UK, and where no patient will ever see his doctor light a cigarette, even if he does belong to the small minority of smokers. "It would be unprofessional, like examining a patient with dirty hands. In your country more than 20% of doctors smoke, as does the remaining population, and it is a desolating daily picture to see staff smoke in hospitals." This is what Professor Michael Fiore, the greatest authority on the fight against smoking in the USA, said to my students at the University of Verona. Exactly, the university. This shows he also knows Italy well. Why is smoking disregarded as a disease in the medical degree course? After all, smoking is responsible for more than 80,000 deaths in Italy every year. The treatment of smoking addiction, which is a real disease, must become essential knowledge for all graduates, as happens for cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, etc. Even if everybody knows that cigarette smoking is bad for you, it is still classed as a "habit" or a "bad habit" and not as a disease; smoking addiction, identified by the WHO, is the main preventable cause of death. Unfortunately, Italian doctors, who do not consider giving up smoking a priority for their patients, are smokers in a percentage similar to that of the general population. It is therefore important to create, among the various people involved, a synergy for greater awareness and education, by modifying wrong beliefs and teaching good behavior practices and effective pharmacological, educational, and psychological strategies.

Briefly, coming back to what concerns us, what is fundamental is not that you do not smoke, but that, if you are a smoker, none of your patients ever see you smoke and that the working environment is totally smoke-free. Allow me to urge you, even if you smoke only a few cigarettes, in the same words Michael Fiore used with my students: "Give up smoking: it is unprofessional for a health worker." This is obviously true for all health workers.

![]()

2 The Smoker: A Stranger

Fabio Lugoboni 1

1 Department of Internal Medicine, Medical Unit for Addictive Disorders, University of Verona, Policlinico GB Rossi, Verona, Italy

Who is standing in front of us? A person with a bad habit he has difficulty losing? A person who does not care about his health? A person who likes risks? Certainly not. Smoking is not a bad habit; it is a form of addiction, and therefore a disease classified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (Table I).

| Psychological addiction | Physical addiction |

- There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control substance use

- A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from its effects

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use

- The substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance

| - The user develops tolerance to the substance, as defined by either of the following: (a) a need for markedly increased amounts of the substance to achieve intoxication or the desired effect; or (b) markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of the substance

- The user experiences withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: (a) the characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; or (b) the same (or closely related) substance is taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms

|

Table I. DSM-IV criteria for psychological and physical addiction

It is obvious that a smoker lights his first cigarette because he wants to, but it is a mistake to think that to continue smoking is a truly willful and free act. Carr puts forward a very good example of this: the action of deciding to go to the cinema is not the same as spending one’s whole life in a multiscreen cinema. Smoking one’s first cigarette affects certain areas in the brain in such a way as to, in an almost imperceptible manner, create conditioning and make buying a notoriously dangerous product acceptable. Imagine just for one moment picking up a yoghurt at the supermarket and seeing these words highlighted on it: "This yoghurt kills." You would undoubtedly be horrified. The mechanism will be explained in detail and in a scientifically traditional manner in the Chapter 13 by Prof. Chiamulera. What is important at this moment is to clarify some basic concepts in order to get rid of any misunderstandings or doubts. Nicotine is certainly a drug from all points of view and is difficult to give up for a variety of reasons. First of all, once inhaled, it reaches the brain very quickly (about 8-10 seconds, more quickly than an intravenous [IV] injection) and therefore complies very well with the definition that a drug is more dangerous the faster its psychoactive action. In addition to this, cigarettes give the smoker the possibility of acquiring perfect drug control much more effectively compared to other drugs. This means that the smoker, through the frequency and intensity with which he inhales, can perfectly dose the substance according to his psychophysical needs: more nicotine if he feels restless, and the nicotine will have a relaxing effect; less nicotine if he requires a stimulating action. If you think about it just for a moment, you have seen your friends who smoke (or who smoked) do exactly that: they smoke slowly and calmly when they are relaxed, but chain-smoke when they are stressed out. From a biochemical point of view, abstinence crises manifest themselves in nicotine addicts with a neurohormonal storm caused by the marked decrease of dopamine at the level of the accumbens nucleus in the mesocortical-limbic system, with a consequent intense stimulation of the prefrontal cortex, which initiates a spasmodic search for a cigarette (drug seeking behavior—think of the smoker who can’t find his cigarettes and starts touching his pockets and rummaging in drawers, becoming more and more frenetic even if, for example, he is already late) accompanied by an increase in the adrenergic tone: the unpleasant feeling of being … in danger of dying without actually being so. All this disappears immediately with the lighting of a cigarette; in other words, just what happens with a drug of abuse. This is its correct name, even if it is sold legally. The term craving describes the desire, almost always unbeatable, of taking drugs, in this case of smoking. Craving is the main manifestation of addiction. This will help you understand some of the phenomena that accompany treatment failure and relapses. Craving can be:

- Induced by lack of nicotine; well, quite obvious: "I haven’t smoked for three days and I’m dying for a cigarette!"

- Induced by nicotine; less obvious: "I haven’t smoked for three months and don’t think about smoking often; yesterday, however, out of curiosity I lit a cigarette and today—damn!—I’m dying for another one!"

- Induced by stimuli connected to cigarettes: "I have successfully stopped smoking for three months but today, here in the pub with my friend John, whom I haven’t seen for months (how many cigarettes we smoked together as students!), I’m dying to ask him for a fag."

- Spontaneous: "I haven’t smoked for three months and I don’t usually miss it. Today, I don’t know why, but I’m dying for a cigarette!" The associated stimulus is not recognized at a rational level, as in the previous case, but remains at a subliminal level. The patient tends to feel defenseless, prey to illogical events he does not control.

It is a good idea to explain to the patient these simple phenomena which are—and you must remember this—temporary. Allen Carr, in one of the examples his readers remember most, describes addiction as a little monster a smoker has inside that pesters him, whining to be fed with smoke: "The only way you can beat it is to starve it: don’t smoke and it will die!" [Carr, 2003]. In actual fact he will fall asleep, just like Sleeping Beauty in the fairy tale, and will wake up only by kissing … a cigarette. The little monster has been asleep inside me for years and I have no intention of waking it up.

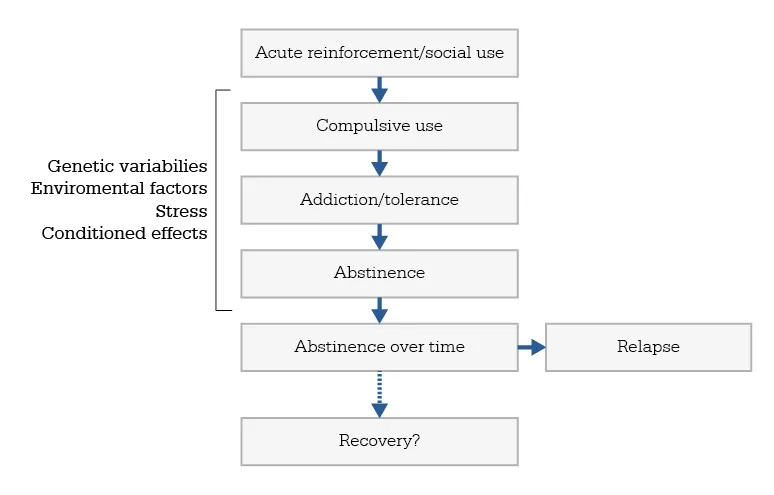

In order to become established, addiction needs a certain number of attempts, just as a fisherman must throw his line into the water several times before catching a fish. How many? Difficult to say. Studies differ on this; we are genetically different, and we live with different people. Nobody will start smoking without a smoker near him. Just to give you an idea, I could say 100 cigarettes; this is the quantity certain studies use to discriminate between smokers, ex-smokers, and nonsmokers, defined as those who have smoked less than 100 cigarettes in their life, since it is difficult to find somebody who has never smoked a cigarette in all his life. A certain number of cigarettes is important to feel an effect, ruling out any emulative aspect, we shall call reinforcement. The stronger the reinforcement (it helps me concentrate, it makes me less shy, it helps me remain thin, etc.), the faster addiction will set in. Smoking is not always pleasant; sometimes it can be quite unpleasant. By continuing to smoke, the young man (because in most cases young people are involved) is able to put smoking in the right place for him, beginning with small episodes of cigarette abuse ("I don’t normally smoke, but at parties I may smoke four or five cigarettes.") which start to create the phenomenon of tolerance. Understanding tolerance is simple and complex at the same time; all you need to know is what you already know, what everybody knows: you get used to some substances, as occurs with a glass of sweet wine, pleasant for somebody who is not a teetotaler, unpleasantly intoxicating for somebody who is. Tolerance, a creeping phenomenon if one doesn’t indulge in marked abuses, makes the brain more sensitive to the gratifying effect of smoking (nicotine receptors increase, the antennae from traditional become parabolic) and, at the same time, more sensitive to the negative effects of lack of nicotine. In order to get round this second effect, one tends to smoke more regularly (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Genesis of addiction [Le Moal, 2007]

Addiction increases until it produces a true abstinence syndrome if one doesn’t smoke. In such a situation the receptors "protest," "complain," just like baby birds who have been left by their mother in the nest without any food. And as soon as the mother returns with a little worm in her mouth, they start fighting. I will now tell you something before you start putting forward easily imaginable objections (I know a lot of smokers who are not like this, even if they have been smoking for years): about 50% of Italian smokers do not develop such a degree of addiction as to experience abstinence symptoms if they don’t smoke—what the English call "going cold turkey", a very vivid way of describing the adrenergic hyperactivity deriving from abstinence. These subjects continue to smoke, even if they know how bad it is for them, under the illusion that they are not addicted because they have not experienced the "cold turkey." They continue to smoke to feel the effect of smoking and not to prevent impending abstinence. If they don’t smoke, they do not feel the need to; rather they feel a latent "malfunctioning" condition, everything loses colour, even if they manage to do the usual things. In other words, the food is still passably good in our favorite restaurant, but service has become sloppy and the staff bad-tempered.

What is the point then of talking about a "smoker" when there are so many different varieties? Quite right, there is absolutely no point: from now onwards we shall always talk about "smokers" in the plural.

"Smokers come in different kinds, about 1 billion, 400 million," my friend Christian Chiamulera, past president of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco (SRNT-Europe) says. With this aphorism Christian summarizes the extreme variability of how and why people smoke. If you think of a grading varying from 1 to 10 and you apply it to different neuromodulators such as adrenalin, noradrenalin (mood, life tone, anxiety), acetylcholine (concentration, intestinal function), serotonin (mood, anxiety, regulation of impulses, sexuality), dopamine (pleasure, vigilance), vasopressin (neurovegetative function), GABAergic (sleep, anxiety) and glutamatergic systems (excitement), you will produce thousands of combinations. You will find the smoker who mainly, but not only, smokes to calm anxiety and the one who smokes to concentrate.

This should not, however, discourage you; after you have helped a few people to give up smoking, you will have an acceptable number of types of smokers at your disposal and be able to do a good job.

But never let appearances deceive you: "Giving up smoking is a process, not an event" (Karl Fagerström).

References

- Carr A. The Easyway to Stop Smoking. London: Penguin Books, 2004

- Le Mo...