- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Cultural History of Money in the Medieval Age

About this book

Money provides a unique and illuminating perspective on the Middle Ages. In much of medieval Europe the central meaning of money was a prescribed unit of precious metal but in practice precious metal did not necessarily change hands and indeed coinage was very often in short supply. Money had economic, institutional, social, and cultural dimensions which developed the legacy of antiquity and set the scene for modern developments including the rise of capitalism and finance as well as a moralized discourse on the proper and improper uses of money. In its many forms - coin, metal, commodity, and concept - money played a central role in shaping the character of medieval society and, in turn, offers a vivid reflection of the distinctive features of medieval civilization.

Drawing upon a wealth of visual and textual sources, A Cultural History of Money in the Medieval Age presents essays that examine key cultural case studies of the period on the themes of technologies, ideas, ritual and religion, the everyday, art and representation, interpretation, and the issues of the age.

Drawing upon a wealth of visual and textual sources, A Cultural History of Money in the Medieval Age presents essays that examine key cultural case studies of the period on the themes of technologies, ideas, ritual and religion, the everyday, art and representation, interpretation, and the issues of the age.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Cultural History of Money in the Medieval Age by Bloomsbury Publishing, Rory Naismith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Economic History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Money and Its Technologies

The “Principles of Minting” in the Middle Ages

OLIVER VOLCKART

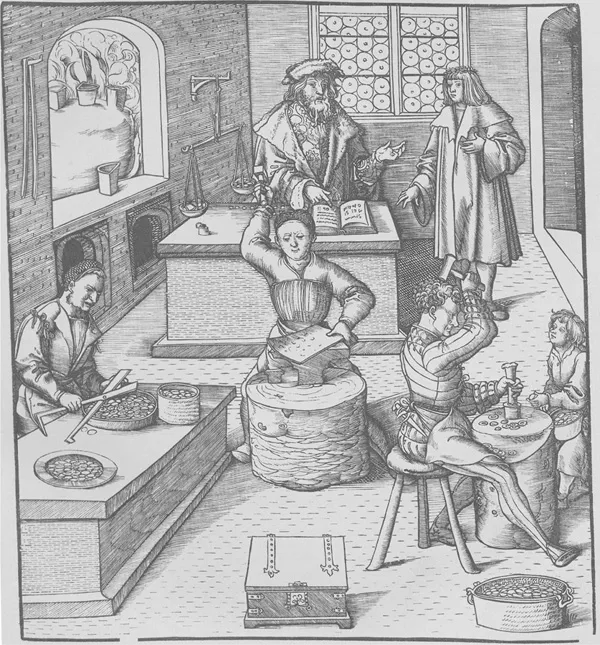

The young White King very often visited his father’s mint and carefully inquired after all the principles of minting, because a mighty king and ruler needs to be acquainted with this art in particular . . . Thus the young White King became most ingenious in minting, considering the use he himself might derive from it, and when he came to rule he ordered the very best coin to be minted, both in silver and gold, better than any other king, and due to his art and experience no other king was his equal in coinage. The same young king also abolished and eliminated all bad and foreign coins in his kingdoms and let new good money be minted in many places, which was to the particular benefit of his people and caused their wealth greatly to grow, as well as increasing his own income from his demesnes . . . And having understood the experience and art of minting, he thought by himself that a king who failed to keep his realm’s mines in order did not draw much advantage from them; hence he diligently inquired about each mine’s nature and which regulations might maintain it best.

—Schultz 1888: 84, author’s translation

This is how Maximilian I (1459–1519), ruler of the Holy Roman Empire from 1486, described an essential part of his education and the resulting policies in his fictionalized autobiography, where he appeared as the “White King.” The work was lavishly illustrated by leading Renaissance artists. Figure 1.1 reproduces the woodcut that shows the episode quoted at the start of this chapter. Below, we will follow Maximilian in his inquiries. We will examine the “principles of minting” about which he questioned his father’s officials as a young man. On that occasion, he not only learned about the tools and implements used to produce coins, but also about fundamental questions of monetary policies. What currency units should a ruler issue? Which metals should his mint use? Should it produce coins that helped increase the ruler’s wealth, or that of his subjects? And, last but not least, in what way should the mint be supplied with the raw material needed for coinage? Maximilian, “the last knight,” was learning how to answer these questions at the very end of the Middle Ages, when more than a millennium had passed since the fall of the ancient Roman Empire in the West. By his time, emperors, kings and other rulers as well as the many coin-issuing towns and city-states that chequered Europe’s political landscape had come a long way, during which their own answers had changed and developed. To a large degree this had happened in response to the changing economic circumstances that affected the demand for money. Before turning to the “principles of minting,” we therefore need to examine these circumstances.

FIGURE 1.1The young White King learns the principles of minting. Woodcut by Leonhard Beck (c. 1480–1542); from Maximilian I’s Weißkunig (White King). http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/jbksak1888/0115

As money is not only a store of wealth and a measure of value, but also a medium of exchange, money demand was to a large degree a function of the importance of exchange. That barter was inconvenient was widely recognized in medieval Europe, as was the utility of money as a means of reducing this inconvenience or, in modern terms, the transaction costs involved in exchange (cf. e.g. Biel 1930: 19ff; Johnson 1956: 4.). How often people engaged in markets and how important the purchase of commodities was relative to self-produced goods, influenced both the absolute size and the structure of their demand for means of payment. The questions were, how much money did society need? And how much of this was small change, useful in day-to-day transactions, and how much high-purchasing power money, needed for example in the wholesale trade? It is important to note at this point that causality was not one-directional: While a growth in trade triggered demand for a larger quantity of money and a more differentiated monetary system, satisfying this demand might encourage a further increase in commerce.

The importance of exchange in the early Middle Ages has been debated. Points of view ranged from the hypothesis that markets were practically non-existent to the idea that exchange was flowering as early as the eighth and ninth centuries (cf. e.g. North and Thomas 1971: 782; Verhulst 2002: 113). The large monastic and noble estates of the Carolingian Empire certainly did sell their surplus, and on small weekly markets consumers could buy simple goods. There was also trade across the borders of the Carolingian Empire: with England, North Africa, Spain, and Byzantium (Verhulst 2002: 97ff.). In fact, according to modern research (McCormick 2002: 778), commerce at this time was already expanding from its nadir in the seventh century. However, there is no doubt that its total volume was still very small and that compared to goods people produced for their own consumption, those bought in markets played a minor role.

The “Commercial Revolution” in the sense of the spectacular growth in local, regional and long-distance trade that Robert S. Lopez had in mind when he coined the term, began to take off only in the tenth century (Lopez 1976: 56ff.). First in Italy and then further north, merchants developed new ways to finance their endeavors (Hunt and Murray 1999: 61). In consequence, the Baltic, Russia, and the Middle East became for the first time firmly linked with western and southern Europe. At the same time increasing numbers of people moved from the countryside into the growing number of towns where they depended on buying the necessities of life. By 1400, the share of people living in places with more than 5,000 inhabitants had increased from practically nothing in the Carolingian age to almost 40 percent in Belgium, 30 percent in the Netherlands, and more than 20 percent in Italy. Even in England it reached 8 percent (Allen 2000: 8ff.).

By that time, Europe was in the throes of the Plague that between its first appearance in 1347 and the end of the fourteenth century killed about half of the continent’s population. How this affected the economy and specifically trade and exchange is another current debate. Robert S. Lopez and Harry Miskimin suggested that the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were a period of economic depression (Lopez and Miskimin 1962); more recent research points to the growth of per capita output, the proliferation of regional fairs and the advances in market integration that took place at this time (Epstein 1994: passim; Chilosi and Volckart 2011: 769; Broadberry et al. 2015: 205).

There are no hard data, but neither is there any doubt that the absolute volume of trade in Europe was far larger at the end of the Middle Ages than at their beginning. What is more, while there certainly were pronounced regional variations, growth seems to have been almost uninterrupted between the eighth and the fourteenth centuries and seems to have continued, at least in per capita terms, even after the Plague. The wheels of exchange kept spinning faster between the seventh and the fifteenth centuries. To oil them, the European currencies did not only need to grow in volume; they also had to be increasingly complex and versatile.

Currencies and Denominations

The currency of the Frankish kingdom of the early Middle Ages was initially that of the late Roman Empire, with the focus being on the issue of gold, in particular on so-called trientes or tremisses that equaled one-third of a Roman solidus (shilling). One of the first measures that caused the Frankish currency to depart from the Roman model was the decision to abandon this triens in the late seventh century. Instead, the mints in the Merovingian kingdom (as in some neighboring regions such as Frisia) focused on the production of silver denarii (pennies) (Grierson and Blackburn 1986: 91ff.). From then on, denarii were the only monetary unit issued, with four equaling one old triens or twelve equaling one shilling (Spufford 1991: 33ff.). We do not know what triggered the reform. There is no evidence for the principles of minting in the pre-Carolingian period. An outflow of gold to the Arab world and the discovery of silver ore deposits in western France probably played a role, but there may have been at least one other motive: The lower value of the denarius implied that it was better suited to small transactions on local markets than the old triens; conceivably, this was taken into account when the gold units were discontinued (cf. Verhulst 2002: 88). Until the eleventh century, denarii remained the only type of coin issued in western and northern Europe. However, the onset of the “Commercial Revolution” presented rulers with a new challenge: how to meet the demand for complex currencies suited to the requirements of both local and long-distance trade. They had three options, which it is useful to consider systematically (cf. Redish 2000: 18ff.).

The most straightforward solution was to produce several denominations made of the same metal and with the same fineness, but different weights. This was the option chosen by the kings of England. They retained the penny, but from the mid-fourteenth century onward supplemented it with a range of other units. The quarter-penny (farthing) had a quarter of the size, weight, and content of pure silver as the penny, while the penny itself was equally carefully matched to its multiples, of which the four-pence piece, called the groat, became most important (Challis 1992: 701ff.). This may to some extent have addressed the problem of providing larger denominations usable in the wholesale trade, but small purchases still presented a problem. Thus, in the 1350s the average price of a tun (252 gallons) of cider was in the region of 12½ shillings (Rogers 1866: 448), which implies that even the smallest piece of money, the quarter-penny, would buy almost half a gallon. Still smaller coins, however, were impracticable. The quarter-penny had a weight of 0.31 grams (Challis 1992: 701)—less than a tenth of that of the physically smallest modern British coin, the five-pence piece. Anything still smaller would have been impossible to handle. How consumers were able to buy small quantities of relatively cheap commodities is not entirely clear. There is some evidence that late Roman low-denomination coins were still circulating in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, as were privately produced jettons (Dyer 1997: 40). However, the use of small-scale credit was probably more important (cf. Nightingale 2004: 51). We need to remember that even at its peak just before the Plague, the total population of England was only about half of that of London today (Broadberry et al. 2015: 20). Most people lived in communities where everyone knew everybody else. Under such conditions it was easy to buy small quantities on credit and to settle the balance once a sum had been reached that could be paid using a coin—which was the case for example after three or four pints of cider.

Another problem posed by the English way of structuring the currency was that producing a quarter-penny cost virtually the same amount of labor as minting a groat, whose value was 16 times larger. To save costs, it was therefore tempting to focus on issuing large coins. In consequence, currencies based on the principle that all denominations should have a proportional bullion content therefore constantly tended to be plagued by a shortness of small change (Sargent and Velde 2002: 49ff.)—if this term is appropriate for coins that had such a comparatively high purchasing power as the quarter-pennies.

The problem of the small size of the lower denominations could be solved by choosing the second and most common option, i.e. by minting them from an alloy of silver and a base metal such as copper, which was comparatively cheap. Nearly all European rulers and cities that issued currencies did this from the twelfth or thirteenth century onward. When, for example, Louis IX (1214–1270)—St. Louis—of France introduced the gros tournois in 1266, whose nominal value was 12 deniers, the new coin was made of almost pure silver. The denier contained about one-twelfth of the amount of silver of the gros, but as it consisted of more than two-thirds of copper, its total weight of 1.11 grams made it large enough to handle comfortably (Blanchet and Dieudonné 1916: 225).

However, this option was problematic, too. For one thing, the costs of testing the bullion content of coins increased when the proportion of base metal of which they were made grew. Hence, issuing money with a high content of copper invited counterfeiting (Redish 2000: 21ff.). More importantly, using base alloys to mint small denominations did not address the issue of the proportionally higher costs their production involved. This problem could only be solved if the fine silver content of the smaller coins was reduced disproportionally. Doing this was dangerous, as St. Louis’s successors soon discovered. Once consumers noticed that the silver content of the denier had been lowered to less than one-twelfth of that of a gros, they began trading the larger unit at a premium. Already by the beginning of the fourteenth century, Philip the Fair (1268–1314) had to acknowledge this, issuing a gros whose official value was no longer 12 but rather 26¼ deniers. The wild fluctuations in the value of the larger silver coins must have made exchange extraordinarily cumbersome, defeating the purpose of issuing a complex currency. Moreover, governments who over-proportionally reduced the silver content of their small change, thereby driving up the value of their larger coins, could be drawn down a slippery slope. To depress the labor costs of producing the small units to a sustainable level, they had to keep reducing the proportion of silver in their smaller coins—with no end in sight. Most avoided this trap, but in extreme cases the policy could end in episodes of rampant inflation (e.g. in Austria in the 1450s: Gaettens 1957/82: 40–51).

FIGURE 1.2Gros tournois (4.22 grams total weight; 4.11 grams fine silver) and denier (1.11 grams total; 0.33 grams pure silver) of Louis IX. https://archive.org/details/manueldenumismat02blanuoft

Moreover, minting authorities that chose this option had to find exactly the right share of base metal in their coinage: It had to be high enough that low-value denominations could be handled with ease, but not so high that the difference between the coin’s nominal value ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Information

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Notes on Contributors

- Series Preface

- Introduction: Money Made the Ancient World Go Around

- 1 Money and Its Technologies: The “Principles of Minting” in the Middle Ages

- 2 Money and Its Ideas: Payment Methods in the Middle Ages

- 3 Money, Ritual, and Religion: Economic Value between Theology and Administration

- 4 Money and the Everyday: Whose Currency?

- 5 Money, Art, and Representation: The Powerful and Pragmatic Faces of Medieval Coinage

- 6 Money and Its Interpretation: Attitudes to Money in the Societas Christiana

- 7 Money and the Issues of the Age: The Plurality of Money

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright Page