![]()

3

Learn the Skills of Leadership

As you advance in your career, you need to learn the specific lessons of leadership. You can learn these lessons from leadership books, you can learn from leaders around you, you can learn from people at other companies, you can learn from reading business history books; there are a lot of ways to learn. When I was early in my career, I learned from looking at the leaders above me in the business organization. I saw what they did well and did not do well.

Once I became a CEO for the first time, I had nobody in the organization to look up to on a daily basis to learn. I had a board that helped me, but I could not learn every day. Then, I found something very surprising; I could learn from people lower in my organization. That view of mine to look above could be reversed to look below, and I could learn a lot of leadership lessons. People in my organization did some magnificent things, far better than I could have done, and I learned a lot from them.

The key is to always be learning. Never stop. Never be satisfied. You can always learn. Focus on learning how to be a leader, and it will help you immensely. Learn how to be a great leader.

Act fast and fix the systemic problem first

One Saturday morning, I got a call from Glen Self. He said Ross Perot and he had another turnaround mission for me and to come into the office on Monday morning with a bag packed. I asked about what the mission was, where it was—all of the normal questions. He only told me to pack work clothes for one week and that they would meet me at 8:30 a.m., Monday, in Ross’s office to tell me what they wanted me to do. Then, I would fly out to the site.

On Monday, I learned that one of the state Medicare and Medicaid contracts was in deep trouble. EDS had a contract to process the claims for this state for its federally mandated but state-administered health-care programs. The situation was dire:

- EDS had operated the contract to process claims for nine months, and they were seven months backlogged in paying claims.

- The governor of the state had called Ross to tell him that the major hospitals in his state were near bankruptcy because they were providing medical services under these programs and were getting no reimbursement because EDS was not paying their claims.

- The governor said that if this situation did not improve quickly, like in a couple of weeks, and in large part, then, he would publicly denounce EDS as incompetent and sue to revoke the long-term contract that was in place.

- And if this was not enough bad news, this single contract was losing money at a rate that, if continued, would consume 50 percent of EDS’s profit for that year. Reducing their earnings by half would result in their public stock price plummeting, losing billions of dollars for their stockholders.

My mission was to fly there, take charge quickly, and start making progress fast. Glen handed me a plane ticket to the state capitol city. The flight was leaving in ninety minutes.

Ross firmly added the following admonition, “I want you to make progress each and every day on improving the performance. I also want you to call me at 5:30 every afternoon to tell me what you did that day that made this account more profitable, not in the future, but that day. I don’t want to hear plans or intentions of future profits. I want to hear how much more profitable we were that day due to your actions. Call Barbara every day at 5:30 p.m., and she will put you in to talk directly with me.”

“Yes, sir!” What else could you say?

I headed to the airport. I started to think about the situation and how these contracts worked. EDS would receive claims from hospitals, doctors, or individuals. These were entered into their computer system where a determination was made of the validity for the claim. If it was valid and the billing fit the tables for that medical procedure, the claim went to be paid and a check was produced. If it was not valid (a simple example would be that the procedure was for an amputation of a leg, and it was the third one for that patient), then, the claim would be rejected with an explanation printed out for the submitting party. If the computer system could not determine the validity automatically, the claim was kicked out to a group of medical professionals for them to make the proper determination of the validity. Obviously, you wanted most claims to be administered in an automated fashion because that was fast and cheap. Once a human had to review the claim, the costs of running the program dramatically increased.

On the EDS revenue side, they were paid a fee for each claim that was paid or rejected. So they were also interested in claims going through the system fast and without that human intervention. In this case, the solution to the governor’s issues and to EDS’s internal profitability issues were the same. We need to be adjudicating more claims quickly.

I knew nothing about what caused these issues, but I knew what the systemic fix was—get claims processed quickly, accurately, and with as little human touch as possible.

I checked my flight schedule and figured that I would arrive at the account at 3:30 p.m., Dallas time. That gave me two hours to make something happen so that I could call Ross that day. Now, most people would think that they had time to do some analysis that first day, but I knew that this was a test by Ross and that he wanted me to call him that day. That was a big challenge, and I was primed to find something fast that I could implement and make it happen before I called Ross.

I came to the account and went to the office of the EDS account manager. He was not expecting me. Nobody had told him who I was or that I was coming. This would have been unheard of in most companies, but EDS in those days was freewheeling and did things like this. Ross and Glen were both action-oriented and always wanted to get results as soon as possible, whether they disrupted the company hierarchy or not.

I met the account manager and told him, “Ross and Glen sent me from Dallas to get things working in this account fast. I will be here and will be in charge until things are working smoothly; then, we can go back to the normal organization. Until then, you work for me as does everyone here. Let’s get started.”

He was taken aback, but he knew enough of the company’s methods, and of Ross, to not discount that this was true. He said, “I hear what you are saying, but before I can start working for you, I need to verify that from my manager. I am sure you know that I have to do that.”

This started a delay process that went on over an hour, as he could not contact his manager or the next level up. I told him that I could call Ross Perot and put him on the phone with us as a quick way to get authorization, but he did not want to do that.

We had killed a lot of time, so my objective of making a first-day impact was not looking good. I had to do something more dramatic to get this moving. I asked the account manager’s administrative assistant if she had an organization chart for the account. She did, and she gave me a copy.

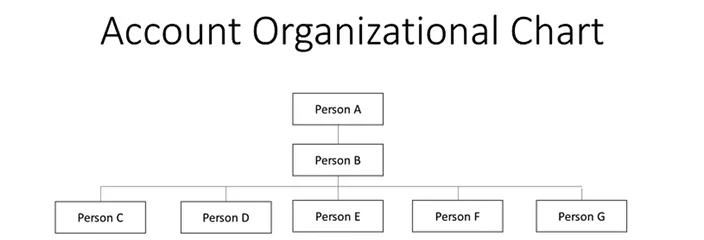

As the account manager was in his office on the phone, I looked at the organization chart and saw the solution! In three places, there was an unusual pattern, like the one below:

At three places in the organizational chart (there were about four hundred fifty people on the account at this time, plus others in training), the unusual pattern of Person A and Person B occurred. I looked at them and marked a circle around the boxes for Person A and Person B. By now, we had less than an hour until I had to call Ross with my results.

The account manager came out and said, “It is late in the day, and I am unlikely to get one of my managers on the phone today. What don’t you go check into your hotel, and we can go to dinner tonight to talk about this. I expect to get one of the managers later tonight or tomorrow morning, so we can start working on this tomorrow.”

“No, that is not going to work. But I have something which we can do today to get this account more profitable. Look at your organization chart. Look at these three odd arrangements of Person A and Person B. I don’t know either of these two people but either Person A is so weak that he can only lead one subordinate, and he needs to be fired, or Person B is so weak that he needs someone to manage him full-time, and he needs to be fired. If you can tell me who is the problem person in each of these circles, we are going to fire the weak one today and let the other one lead the group.”

Now, a complicating factor was that this account manager’s name was in one of circles! He was a Person A type, and he had only one person reporting to him who managed everyone else in the account.

He replied, “I see your point, but we are not going to do that today. I don’t even know who you are, and to fire people because some unknown person walked into my office is ridiculous.”

“So we agree that the situation in all of the circles is intolerable and needs to be corrected.”

“Yes, I can agree with you on that, and I was working to get it done.”

“So all we are talking about is timing. You can verify who I am by calling Ross. Let’s walk into your office and do that.”

“I am not comfortable with firing someone until I can verify that this is working. I need to talk to my managers, not Ross Perot.”

This is the kind of bureaucratic behavior that I knew infuriated Glen and Ross, as well as me. We needed to be more agile and more aggressive. So I decided that I needed to push him into action by tel...