- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

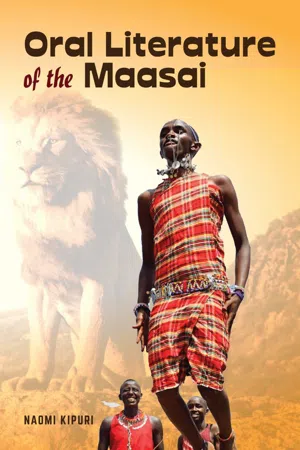

Oral Literature of the Maasai

About this book

Oral Literature of the Maasai offers an extensive collection of types of oral literature: oral narratives; proverbs; riddles; and a variety of songs for different occasions. The versions in this book were collected by the author from a specific Maasai community in Kajiado County of Kenya. The author listened to many of the narratives and participated in many proverb and riddle telling sessions as she grew up in her Ilbissil village of Kajiado Central Sub-county. However, she recorded most of the examples of oral literature in the early seventies with the help of her mother, who performed the role of the oral artist. Many songs were recorded from live performances. The examples ring with individuality, while also revealing a comprehensive way of life of a people. The images in the literature reveal the concrete life of the Maasai ñ people living closely with their livestock and engaged in constant struggle with the environment. But like all important literature, the materials here ultimately reveal a people with its moral and spiritual concerns, grappling with questions of human values and relations, struggling for a better social order.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Oral Literature of the Maasai by Naomi Kipuri in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER THREE

Narratives

Narratives are often classified according to their function. While this kind of classification is convenient, it does not prevent an inevitable overlap of categories. For this reason, no classification of narratives, and other forms of oral literature, should be adhered to rigidly.

Narratives included in this book include myths, legends, ogre tales, trickster and other animal tales, and man stories. Under myths, we have narratives that explain the origin of various phenomena. As explained in Oral Literature: A School Certificate Course by Akivaga and Odaga, these are narratives that contain explanations about a community’s origins and early history. Story 1 is an attempt to explain the origin of a most intriguing eventuality, death.

The story goes that the first man was granted a password by which to avert death. But either through forgetfulness or malice, he reversed the password, thereby placing man in a vulnerable position, in relation to death, and endowing moon with the ability to survive it. In narrative 2 we are offered a socio-cultural explanation for the reason why the sun shines brightly, but the moon does not: the sun beat the moon “in the same way husbands beat their wives”. Even an irregularity like the wife fighting her husband is explained in cultural terms: the moon is one of those short-tempered women who beat their husbands.

Explanations offered in these myths are imaginative; most of these narratives could be described as aetiological. They are also called “the how and why” stories because they explain the origin and characteristics of various animals, plants, features of the landscape, or different social customs. In such explanations, there are often cultural additions and some rather marvellous and anachronistic colourings that make it almost impossible to separate the true element from the traditional or socio-cultural. Thus the cause of the embarrassment felt by the sun, but not by the moon in story 2 is based on the traditional norms and expectations of the society. A husband would not walk about undaunted with a wound that was inflicted by his wife!

A common feature of myths is their reference to emotions and experiences that are universally understood and felt. In narrative 3 we are told that the fight between the gods is based on the difference in their respective natures: while the black god is kind and loving, the red god is malevolent and cruel. Sacred beings are by no means set above human beings; they fight and are preoccupied with petty jealousies; and the fact that an essential commodity such as water becomes the bone of contention is significant and expected in a semi-arid region.

Some myths embody customs that are still very strongly observed. Others serve the interests of the community by justifying good as well as evil practices, or illustrating the consequences of good as well as bad behaviour. In story 4 the Dorobo hunter, through no fault of his own, expresses surprise on seeing cattle descend from a thong, and for this he is cursed to hunt game forever. This myth, therefore, justifies subjugation of the hunters by the pastoralists even to the present day. Another myth (5) explains how women irresponsibly let their cattle wander away and get lost. This illustrates not only why women do not own cattle, or any property, but also justifies their maltreatment. The same is true of narrative 6 where marriage is said to have been caused by woman’s lust. It implies that if marriage has evolved into a necessary evil for women, it was brought about by one of them. The significance of this myth rests in the fact that voluntary celibacy does not exist traditionally among the Maasai.

The belief system and social values of a community are conveyed in some of its myths. Some stories (not included) explain the appearance, shape and behaviour of insects. We are told that Louse disobeyed her grandmother, was cursed by her, and became paralysed enabling even a blind person to catch her. Flea, for his part, was obedient, and for this he was showered with blessings, which made him swift and able to manoeuvre between the fingers of human predators. The consequences of the curse and blessing in the respective cases is a way of saying that the young have to obey their seniors in order to receive blessings. Failure to obey could result in the young being cursed, which would in turn lead to grave consequences.

In another narrative Louse, envious for not possessing the much admired sword, tricks her friend Termite into tightening his sword belt to the extent of almost cutting through his waist, and ending up with a ridiculous shape. But the mischievous trick makes Louse laugh to the extent of splitting her nose. Therefore, while Termite suffers from an ugly shape, Louse, who bears responsibility for it, consequently loses perhaps a very valuable part of her body. The explanatory element is a common feature in myths, although the explanation does not necessarily have to be stated explicitly. The function of the above myths in illustrating the consequences of good and bad behaviour is only made by implication.

Most myths are simple to follow. Each myth often illustrates the consequences of one or two aspects of social behaviour. There are, however, other narratives in this category that are relayed in a complex manner to encompass multiple facets of a myth. Narrative 7 is a fine example. The dog defies god’s orders and betrays the sheep. For this he loses favour with god, is sent down to earth, where he becomes a servant of man, who in turn obtains god’s favourite creature, the sheep.

Both animals get re-named: Dog requests qualities he needs for survival in his new and unpleasant environment. These he is given. The myth illustrates his peculiar characteristics and the establishment of the triangular relationship between god, dog and man. This is a complex narrative since it contains several myths within it, and various illustrations of differing behaviours.

Legends

Stories 8 and 9 are legends. They are about events and people in a historical context within a particular community. They also revolve around historical figures, characters or events. The basic difference between myths and legends is that while a legend is told as if it is true, and is often based on true events or characters the veracity of a myth is based on the beliefs of its hearers. In narrative 8 the present clan system among the Maasai is explained in very precise detail; this makes it sound like a simple description rather than a story. But the fact that the clan system, as explained here, conforms to the present system in all detail removes the mythical element and makes it a legend.

Narrative 9 is an example of a hero legend; these are common in many communities. The hero always has super-human qualities. The Arinkon leader is said to be mighty and strong like a giant; Lwanda Magere, a legendary character from among the Luo community had a body made of rock and strength was in his shadow. It is significant, however, to note that the giant in story 9 is not a Maasai hero, and that his strength and bravery only go to indicate how clever his conquerors were. The heroism is interestingly shifted to the clever boy who kills the giant. This is a David and Goliath type legend, and it is intriguing to imagine how it would have been told by the Arinkon themselves.

Animal Stories

The animal stories included in this book fall into two categories. First, there are those that revolve around adventures of weird creatures and their encounters with the human beings. These creatures, like the warrior with two mouths or a crow-like suitor, are formless and are not easily visualized or described. Some have names like Mbiti, Konyek, Ntemelua, but they are all lumped together in Maa as nkukuuni or ng’wesi, which translated means some fearful monster or ogre. The second category includes trickster tales and tales of other animals with clearly identifiable animal characters.

In the first category of narratives, one can identify common features in the monster characters. Although this is not stated in each case, these ogres are all unusual in one way or another. Each has some outstanding characteristic. The warrior in story 1 has two mouths and is also strikingly handsome; the crow in 13 is also an attractive young man; Mbiti (11) alone of all other monsters has a cowrie shell on the tail that eventually betrays her; Konyek (12) has protruding eyes from which he got his name; and Ntemelua (15) is significantly portrayed as a new-born baby in order to highlight the marvellous nature of his grotesque behaviour.

Another aspect that is evident in ogre tales is their portrayal as greedy and cruel creatures. Mbiti’s monstrosity is seen in the way she makes the girl choose whether to be eaten or spared. The girl chooses the latter, and the monster indeed brings her up like a beloved daughter. But when she grows fat Mbiti begins to view her as potential food, and keeps pricking her to determine whether she is ready for the table. Konyek kills his aunt and takes his twin cousins to be roasted for kidneys. The crow taunts his bride instead of eating her immediately, and the ogre (14) does the same to the young woman.

Ogres are also portrayed as potentially intelligent, but their intelligence is never utilized at the right time. The warrior monster has suspicions that he was betrayed by the warrior who had put on a squint and a limp. Mbiti is suspicious of the girl who called herself “a skin of ashes” and questions her a second time about her identity before dismissing her; Konyek’s premonition is quite outstanding, but the presence of his father in the story as a perfect dupe is a deliberate stylistic feature to prevent his eventual triumph. The crow tricks both of the girls’ parents and succeeds in obtaining the bride; he is about to succeed when unexpected rescuers are introduced. This technique, stylistically known as deus ex machina, is commonly employed in ogre tales when a sure end seems imminent for the hero or heroine.

Another interesting factor in ogre tales is their beginning and the way the would – be victim starts by forgetting something, or having one reason or another to return in order to recover it, and ends up by being a victim of the ogre. The girl in story 12 forgets her beads on the monster’s bed; when she goes to recover them she puts herself into the hands of the monster. In story 11 the youngest of the girls, having been tricked by the others, picks unripe berries; she returns for ripe ones, in anger and determination, only to become a victim of the ogre; again the young woman (notice how most victims happen to be women!) in pursuit of her warrior lover (14) confuses the left with the right path, takes the wrong path, and consequently meets the monster.

Another interesting aspect is the way songs are introduced into monster narratives, initially as laments, but at the same time signal an alarm that results in the rescue of the victim. The crow’s bride (13) having resigned herself to a fateful end sings out her last wish (if only her stubborn parents were there to see for themselves!). Although she is much too far away from home and has no hope whatsoever of being rescued, the girl’s song alarms the passers-by who immediately come to her aid. In story 14, the woman composes a song that flatters the ogre, keeps the audience in suspense, but also brings forth the desperately needed help.

Finally, the ending of ogre narratives is significant. There are numerous Maasai monster stories, and many of them have different endings. The commonest is the one in which the monster gets killed, or opened up, and the victim is rescued. Others normally request that some part of themselves – thumb or little finger – be cut to let out all the victims (15). Yet others bring about their own deaths. Mbiti (11) collects all the other monsters to feast on her victim,but she ends up being the victim of her friends; Konyek (12) and his father find “kidneys” which they bring up, not knowing that they will be the cause of death for both of them; the crow (13) lights a big fire in which to roast the bride, but he gets roasted in it instead; and the ogre (14) prepares a bed of sweet smelling leaves on which his flesh (not his victim’s) is laid after his death. Yet again mysterious creatures like Ntemelua (15) disappear in equally mysterious ways.

These types of narrative entertain ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Preface

- Sources of material

- Orthography

- Introduction

- The Dominant Features and Style of Maasai Oral Literature

- Narratives

- Riddles: Iloyietia and Ilang’eni

- Proverbs: Ndung’eta-e-rashe

- Songs and Poetry

- Bibliography