- 150 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Global Business Strategy

About this book

Global Business Strategy looks at the opportunities and risks associated with staking out a global competitive presence and introduces the fundamentals of global strategic thinking.

The authors demonstrate how a company should change and adapt its domestic business model to achieve a competitive advantage as it expands globally.

Our framework includes a company's business model, the strategic decisions a company needs to make as it globalizes its operations, and globalization strategies for creating a competitive advantage. A business model has four principal dimensions: market participation, the value proposition, the supply chain infrastructure, and its management model.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Global Business Strategy by Cornelis A. de Kluyver,John A. Pearce, II in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Unternehmensstrategie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

The Global Competitive Environment

CHAPTER 1

The Globalization of Markets and Competition

Introduction

This first chapter considers the economic, political, technological, and cultural dimensions that have propelled globalization, as well as factors that are checking its progress. Second, we discuss the shift of the center of gravity of global competition from the West to Asia and consider how global competition is evolving. Third, we deal with industry globalization and assess the growing complexity of the global competitive environment. We conclude the chapter by looking at the benefits and costs of globalization.

Defining Globalization

The integration of national economies into a global economic system has been one of the most important developments of the last century. This integration process, called globalization, has resulted in remarkable growth in trade between countries. Globalization is manifested as a growing economic interdependence among countries at a macro level, reflected in the increasing cross-border flow of goods, services, capital, and technical knowledge. At the company level, globalization refers to the increasing percentage of revenues and profits derived from foreign markets.

Economic globalization started as countries lowered tariffs and nontariff barriers, and international trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) grew. As more and more countries embraced free-market and anti-protectionist policies, the globalization of production and markets ensued. The globalization of production allowed companies to spread parts of their manufacturing operations worldwide to reduce costs. The globalization of markets has led to an increased focus on the world as a huge global marketplace rather than a collection of local markets, which has produced a measure of convergence in consumers’ tastes and preferences.

Among the growth-enhancing factors that come from greater global economic integration are (1) competition: companies that are not focused on innovation and cost-cutting are likely to be replaced by more dynamic firms; (2) economies of scale: firms that export to the world have lower unit costs, which allow them to be more competitive; and (3) learning: companies that operate internationally are more knowledgeable about global competition, innovations, and evolving industry standards.

The globalization of production and markets has had enormous implications for companies. First, it has forced companies to recognize that industry boundaries no longer stop at national borders, and competition can originate abroad. Second, as relatively protected national markets became segments of a more integrated global market, they noted competitive rivalry increased because many firms competed with each other for market share and profits around the globe. Third, with a larger number of competitors, suppliers, customers, and a greater diversity of needs and preferences, the rate of innovation increased, compressing product life cycles and increasing consumer choice.

As globalization increased, it also became more complex. Beyond economics, its dimensions have grown to include technological, political, and cultural considerations that increasingly impact the decisions of nations, companies, and individual consumers. Globalization has brought down prices, increased choice, and provided growth opportunities. Simultaneously, as different areas of the world have become more integrated, the world economy has become more vulnerable to global shocks—from global warming to a financial crisis and, more recently, the global COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. These changes have made it imperative for companies to understand how they should deal with the growing complexity of the global economic, technological, political, and cultural landscape.

Globalization or Regionalization?

While the term globalization is widely used, from an economic perspective, it is more accurate to speak of semiglobalization or regionalization because global trade and investment is largely concentrated in three sets of relationships—between the United States and the European Union (EU), the EU and Asia, and Asia and the United States, frequently referred to as the Triad. The EU and the United States have the largest bilateral trade and investment relationship in the world. EU and U.S. investments are the principal drivers of the transatlantic relationship, contributing to growth and jobs in both the E.U. and the United States.1

Asia and Europe are leading trade partners, with 1.5 trillion U.S. dollars of annual trade in goods. The two continents are moving quickly to build and strengthen ties, with a firm commitment to agree to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainable connectivity has become a focal point of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM), an intergovernmental cooperation forum between 30 European and 21 Asian countries. Trade within Europe and Asia is four times higher than the trade between the two regions. However, the trade between the Asian and European regions is still higher than that between any other world region. Russia is the third-largest trader in the ASEM group of countries; it exports twice as much to Europe as Asia.2

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in 2015 to 2017 (the latest years for which accurate statistics are available) between Asia and Europe reached close to 90 billion U.S. dollars annually—nearly the same level as FDI flows within Europe. Over half of European investments in Asia come from the United Kingdom and Germany. Similarly, China and Japan are the principal investors from Asia in Europe, while India and China account for around half the total European foreign investment.

U.S. trade with Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was 272.0 billion U.S. dollars in total (two way) goods trade during 2018. Goods exports totaled 86.2 billion U.S. dollars; goods imports totaled 185.8 billion U.S. dollars. The U.S. goods trade deficit with ASEAN was 99.6 billion U.S. dollars in 2018. Trade in services with ASEAN countries (exports and imports) totaled 55 billion U.S. dollars in 2017 (latest data available). Exports were 33 billion U.S. dollars; services imports were 22 billion U.S. dollars. The U.S. services trade surplus with ASEAN countries was 10 billion U.S. dollars in 2017 (latest data available). U.S. FDI in ASEAN countries (stock) was 328.8 billion U.S. dollars in 2017 (latest data available), up 5.6 percent from 2016. U.S. direct investment in ASEAN countries is led by the nonbank holding companies, manufacturing, and wholesale trade sectors.3 This evidence supports the notion that global trade is still largely semiglobal or regional is likely to remain that way for some time.

Globalization’s Four Underlying Dimensions

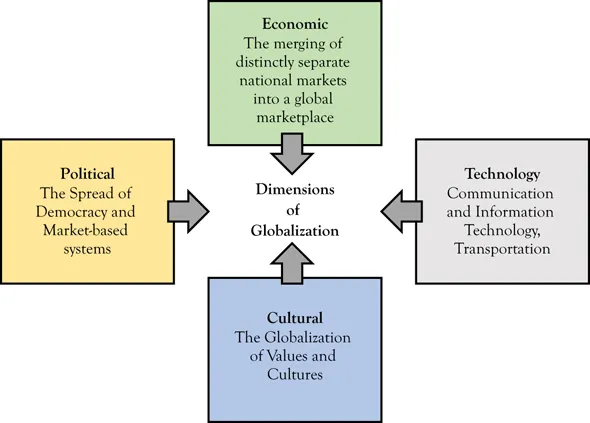

Globalization has grown in complexity to include four sets of drivers: (1) ongoing changes in the economic arena, (2) advances in technology, (3) the convergence of political ideas, and more recently, (4) the growing integration of values and cultures around the world (see Exhibit 1.1):

The economic dimension. The economic dimension of globalization is rooted in free trade. Chapter 3 reviews the principal economic and regulatory constructs that define the current global trading environment. For many companies, foreign sales have become an increasing or even dominant portion of their total sales. Market size is of particular importance to companies that produce goods and services that have a high research and development (R&D) intensity or capital expenditures. If their potential customer base is small, developing and producing a product is significantly costlier. Growth of markets abroad helps firms spread development and production expenditures over a larger revenue base. This is often referred to as the scale benefit of globalization.

Globalization has created opportunities for specialization. Specialization makes it easier to enter new markets, especially when it is not necessary to be large with strong existing ties to customers. Specialized markets usually have greater space for new companies and can compete based on new technologies and ideas. For example, a high-quality producer of automobile engine components does not need to compete with larger firms such as Ford and Toyota in the end customer market. Rather, it can allocate all of its resources to become even more competitive in designing engine components. That means, among other things, that resources (e.g., staff and technology investments) can become more specialized.

Exhibit 1.1 Dimension of globalization

Companies that can leverage the benefits from trade, such as scaling up and specializing production, also create better-paying jobs that demand greater skills. These benefits tend to be strongest in economies that are open to trade and investment. While outsourcing and off-shoring sometimes lead to unemployment, wages and employment levels tend to be higher because trade enhances human resources efficiency. When some parts of the production are off-shored, companies can specialize and invest more in human capital.

Globalization has resulted in lower consumer prices and increased living standards. While this benefit has primarily accrued to Western economies, developing countries are catching up due to freer and higher levels of trade in the world.

Consumer choice and product variation have increased. Between 1972 and 2001, the number of goods in the U.S. economy doubled to 16,000, while the median number of countries from which a good was imported rose to 12.4.

Globalization has also promoted economic efficiency in the world economy.5 Economies of scale and specialization have improved resource use in the economy. As a consequence, labor productivity has increased.6 Moreover, the fragmentation of value chains has boosted productivity through lower-cost imports of inputs.7 Trade and investment improve the technology of sectors and economies by forcing greater competition upon incumbent firms. The top 10 percent of U.S. firms in productivity is twice as productive as the bottom 10 percent.8 In Europe, the top 10 percent of firms are three times as productive as the bottom 10 percent.9

Globalization has reduced inflation in Western economies and increased real wages by lowering the cost of consumption. Many goods that previously were affordable by only a few—for example, a mobile phone or car—are common in many households. Globalization also has stimulated the spread of new technologies, making economies greener and more productive. Finally, globalization has helped reduce gender wage discrimination, provide new opportunities to women, and improve management and working conditions.

Two impending changes in globalization’s economic dimension are noteworthy. First, trade in commercial services is growing faster than the trade in goods. Second, the demand for goods and services is gradually shifting eastward. By 2030, developing countries, led by China, are expected to account for more than half of global consumption.

These changes are creating new challenges for companies and nations alike. Companies will have to (1) carefully monitor how these global trends affect their business model(s), target markets, and how value creation is shifting within their industry; (2) enhance service offerings; (3) build closer and more digital supplier relationships; and (4) focus on costs, risks, speed, flexibility, and resilience in their strategy development.10 Nations face equally serious challenges. Countries will need to (1) strengthen their service sectors, (2) embrace automation in all value chains, (3) deepen regional ties, and (4) invest in R&D and skill development. Countries have already begun to specialize. Analysis by McKinsey and Company shows how countries are focusing their trade on specific sectors of the economy and are assuming specific roles in the value chain. For example, Germany, Japan, and South Korea are innovation providers in automobiles, pharmaceuticals, and chemicals. The United States, France, and the United Kingdom are service providers in financial intermediation, telecom, and information technology (IT). Other countries can be classified as regional processors (e.g., Finland for paper), resource providers (e.g., Australia for mining), or labor providers (think of China in textiles).11

According to the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), developing a robust global digital identification system for individuals and companies will be key to unlocking future global growth. Many people in the world do not have any form of identification that is usable in the digital world and cannot access important governmental or economic services. Individuals will be the major beneficiaries of digital identification (ID) through (1) increased access to and use of financial services...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Description

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I The Global Competitive Environment

- Part II Global Strategy Development

- Part III Global Strategic Management

- Notes

- References

- About the Authors

- Index

- Backcover