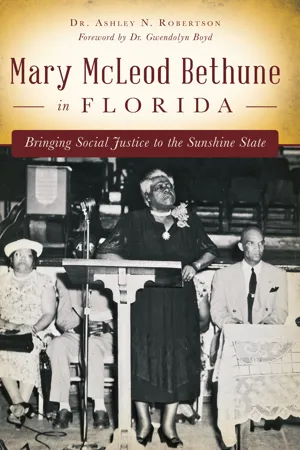

eBook - ePub

Mary McLeod Bethune in Florida

Bringing Social Justice to the Sunshine State

- 213 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A vibrant biography of the woman who shaped the political climate of Daytona Beach with her civil rights, women's rights, and education activism.

Mary McLeod Bethune was often called the "First Lady of Negro America," but she made significant contributions to the political climate of Florida as well. From the founding of the Daytona Literary and Industrial School for Training Negro Girls in 1904, Bethune galvanized African American women for change. She created an environment in Daytona Beach that, despite racial tension throughout the state, allowed Jackie Robinson to begin his journey to integrating Major League Baseball less than two miles away from her school. Today, her legacy lives through a number of institutions, including Bethune-Cookman University and the Mary McLeod Bethune Foundation National Historic Landmark. Historian Ashley Robertson explores the life, leadership and amazing contributions of this dynamic activist.

Mary McLeod Bethune was often called the "First Lady of Negro America," but she made significant contributions to the political climate of Florida as well. From the founding of the Daytona Literary and Industrial School for Training Negro Girls in 1904, Bethune galvanized African American women for change. She created an environment in Daytona Beach that, despite racial tension throughout the state, allowed Jackie Robinson to begin his journey to integrating Major League Baseball less than two miles away from her school. Today, her legacy lives through a number of institutions, including Bethune-Cookman University and the Mary McLeod Bethune Foundation National Historic Landmark. Historian Ashley Robertson explores the life, leadership and amazing contributions of this dynamic activist.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mary McLeod Bethune in Florida by Ashley N. Robertson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

$1.50, Faith in God and Five Little Girls

The Founding of Bethune-Cookman University

Mary McLeod Bethune was born to Patsy and Samuel McLeod on July 10, 1875, near rural Mayesville, South Carolina. She was the fifteenth of seventeen children and the first to be born into freedom. As she was the first of her parents’ children born free, there were a lot of expectations for her life. Freedom had been a dream, and her life held unique promise because of it. When opportunities to further her education came along, young Mary did not pass them up. She attended Scotia Seminary in Concord, North Carolina (graduated in 1894), and thereafter Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, Illinois (graduated in 1895). It was after Moody that she attempted to go to Africa as a missionary, but the Presbyterian Mission Board explained to her that it was no longer allowing black missionaries to go to Africa. Although her dreams were temporarily crushed, she decided to become a teacher. Lucy Craft Laney, an educator who had opened her own school in Augusta, Georgia, offered her a position as a teacher at the Haines Normal and Industrial School. Haines was the first school for African Americans in Augusta, and it was there during her short tenure (1896–97) that Bethune adopted the idea of starting her own school and received valuable mentorship from Ms. Laney. Like Bethune, Laney was born free to formerly enslaved parents. The following year, while teaching at Kendall Institute in Sumter, South Carolina, Mary McLeod met and married a young teacher named Albertus Bethune. Nine months later, on February 3, 1899, the pair became parents when Albert McLeod Bethune was born.

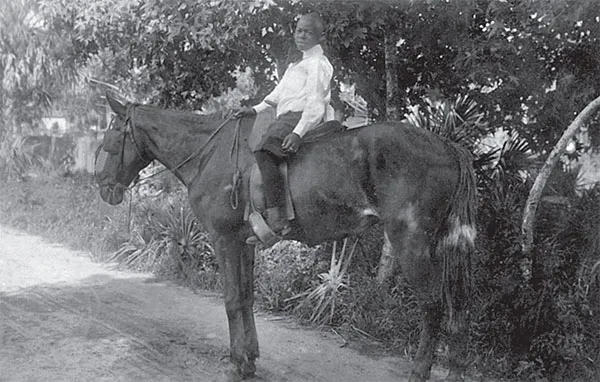

Albert McLeod Bethune Sr. as a child. Courtesy of the Bethune-Cookman University Archives.

After living for a while in Savannah, Georgia, the family moved to Palatka, Florida, where Bethune started a small mission school at the urging of a native Presbyterian minister. After almost five years in Palatka, she was encouraged to move to Daytona since there were several African Americans moving to Daytona Beach to work on the railroads. This meant there would also be children moving, and they would be in need of an education. In September 1904, Bethune arrived in Daytona Beach with her son; her husband stayed behind in Palatka to conduct business. With $1.50 in cash, she looked for a place to rent and was able to convince the owner of a four-bedroom home to let her rent it for $11.00 a month, although she did not have all of the rent up front. On October 3, 1904, she utilized the home to officially open the Daytona Literary and Industrial School for Training Negro Girls with her son and five little girls: Lena, Lucille and Ruth Warren; Anna Geiger; and Celest Jackson.

At the time that Bethune arrived, Daytona Beach was a very progressive area. It was established in 1876, and blacks represented about half the population and had built their own stores and churches. Wealthy whites also maintained winter homes in Daytona Beach. She saw both of these populations as those that could be of assistance in starting her school. Local African Americans, including carpenters, helped build the first building—Faith Hall—while others donated dishes and food from their gardens. The black Daytona Beach community was the backbone of the school, providing much-needed encouragement. To stabilize the school and to expand her network, Bethune established an impressive board of trustees that included James N. Gamble, the wealthy co-owner of Proctor and Gamble. In the early years, she sold sweet potato pies as a way to raise funds; she also sold boiled eggs to local railroad workers for lunch. After a separation from her husband around 1907, Bethune continued to grow the school and reach out for assistance on her own. Expanding on her fundraising efforts for the school, she took her students to sing for wealthy whites who were visiting Daytona Beach on vacation and collected donations. Thomas White of White Sewing Machine Company also became a supporter of the school after seeing a performance by the school’s choir. Bethune established a relationship with John D. Rockefeller, a very wealthy philanthropist and owner of Standard Oil Company, to assist with fundraising. She also enlisted the help of Booker T. Washington, founder of Tuskegee Institute, who visited her at the school in 1912. He was instrumental in helping her establish relationships with wealthy philanthropists, and she became good friends with his wife, “Lady Principal” Margaret Murray Washington. The pair later became involved in the 1920 founding of the International Council of Women of the Darker Races, an organization that was concerned with the worldwide condition of people of African descent.

An early photo of students at Faith Hall, along with teaching staff and Mary Bethune, in 1920. Courtesy of the Bethune-Cookman University Archives.

The earliest known pictures of Mary Bethune and her all-girls school. Courtesy of the Bethune-Cookman University Archives.

Under Bethune’s leadership, the school expanded and underwent several changes, particularly its name. By 1919, the school had made its third name change, transitioning from Daytona Educational and Industrial Institute to Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute. In 1923, the all-girls school began the process of merging with Cookman Institute, a coed school led by the Methodist Church. Founded in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1872, it had also been the first school to offer higher education to African Americans in the state of Florida. Although the merging of Bethune’s school and Cookman Institute began in 1923, it was not until March 1925 that it became complete, and both schools collaborated to become the Daytona Cookman Collegiate Institute. Following the merger, Bethune served as president from 1923 to 1942 and from 1946 to 1947. In 1931, the school became officially known as Bethune-Cookman College. Although there were several schools founded by and for women, it was rare for African American women to serve as college presidents during Bethune’s time. In fact, even Spelman College, which was founded for African American women in 1881, did not gain its first female African American president, Dr. Johnnetta Cole, until 1987. Howard University, founded in 1867, did not see its first black president, Mordecai Johnson, until 1926. For Bethune to become a college president in 1923, she was well before her time.

By 1928, the school had expanded and offered junior college and college preparatory courses; it also offered students the opportunity to gain specialized experience in its School of Commerce and School of Music, among others. The school also invested in a new Drama Department, and literary giant Zora Neale Hurston taught there for a brief time in 1934. During her tenure as president, Bethune continued to add various programs and trainings to enhance the students’ skill set. She also ensured that the football team, started shortly after the merger, remained a part of the school, despite the fact that, initially, it cost the school quite a bit to maintain it. She vowed to raise the money to keep the program alive, and she did.

Digging deeper into civil rights activism, Bethune also served in advisement positions for four U.S. presidents. She served as a delegate to the Child Welfare Conference under Calvin Coolidge and worked on the National Committee on Child Welfare under the leadership of Herbert Hoover. During Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s presidency, he implemented a number of programs under the New Deal, including the National Youth Administration (NYA). NYA was designed to provide work relief to students from ages sixteen to twenty-five. At the time, unemployment was at an all-time high, and the programs were particularly beneficial for African Americans. It also provided “student aid” to students of the same age who could no longer afford tuition. Bethune was appointed to be a representative on the advisory committee for the NYA along with Mordecai Johnson. In 1936, Roosevelt appointed her to a larger role as the head of the Office of Minority Affairs under the NYA program, making her the first black woman to head a federal agency. As the head of the division, she ensured that African Americans received their fair share of federal funding. She also ensured that African American colleges were included in the Civilian Pilot Training Program, which led to the graduation of some of the first African American pilots in the nation. The division came to an end in 1943. Under Harry Truman’s administration, she served as a consultant on interracial relations and as an international delegate.

Mary Bethune dedicating the campus Log Cabin in 1939. This cabin was used for student social events. Courtesy of the Bethune-Cookman University Archives.

The B-CC agricultural stand where students sold harvested goods. Courtesy of the Bethune-Cookman University Archives.

Bethune-Cookman College, Daytona Beach, Florida academic exhibit in 1926 displaying renovated dresses made by the students.

After years of success as both the founder and president of B-CC, Bethune’s busy schedule took a toll on her, and in 1941, she made the decision to retire the following year. On December 15, 1942, Dr. James Colston was elected as the second president of B-CC.

SUNDAY COMMUNITY MEETINGS AND THE PROTEST OF SEGREGATION

Mrs. Mary McLeod Bethune’s refusal to set up a special section at her school for white folk when Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt spoke there, was indeed a noteworthy and courageous act. By so doing she made the thirty-fifth anniversary celebration of Bethune-Cookman College, of which she is president and a founder, an epochal event, for it is unusual that a Negro in the South balks at the bidding or requests of the white folk.

During the early 1900s, when Mary McLeod Bethune came to Daytona Beach, the town was segregated, with railroad tracks as the barrier separating African Americans from the rest of the town. Less than a decade before her arrival, the landmark decision in Plessy v. Ferguson declared that separate but equal facilities were legal. The case brought a clear message that segregation was now the law, and throughout much of the United States, it was practiced with vigor. Midtown, the prominent center of the African American community in Daytona Beach, was filled with churches, black-owned businesses and homes. Mrs. Bethune built her school in the heart of Midtown. Over the years, she created a space for African American students and faculty/staff members to flourish through academic success, community activism and the development of young minds. Although she was able to build a safe haven, segregation permeated throughout the city even decades after she successfully established the school as a college.

Mary Bethune and Dr. James Colston in 1943 as she resigned from her presidency. Courtesy of the Bethune-Cookman University Archives.

Working as a photographer for the Office of War Information in 1943, Gordon Parks was sent to Daytona Beach to capture Bethune-Cookman College and Midtown. His groundbreaking photographs showed B-CC students producing farm vegetables, training in automobile mechanics and learning skills, including welding and sheet metal work, through the National Youth Administration to support World War II efforts. While he focused largely on B-CC, Gordon took a unique look at black Daytona, particularly Midtown’s Second Avenue area. He featured the Pinehaven housing projects; children of laborers; historic churches, including Stewart Memorial; and local businesses with patrons relaxing outside on the porches. For many who knew Daytona Beach as the “World’s Famous Beach,” it was a completely different place when you saw Parks’s pictures filled with black faces and no beaches in sight. Although his work didn’t comment on the fact that blacks were not allowed to go to the beach, it was clear that Midtown was their own community, completely separate from the rest of the city.

Sunday Community Meetings at B-CC. Courtesy of the Bethune-Cookman University Archives.

Mary Bethune and First Lady Roosevelt at B-CC. Courtesy of the Bethune-Cookman University Archives.

In her position as founder of Bethune-Cookman College, Bethune utilized the school as a space to protest the practices of segregation. As early as the 1920s, all races could be seen in pictures sitting together as a result of integrated seating policies during the school’s Sunday Community Meetings. In a 1937 article in the Literary Digest about Bethune’s work at B-CC, the issue of integration on the campus was discussed: “When white people come to call there are no special seats set aside for them. ‘Once within the walls of the college,’ says its founder, ‘there are neither blacks nor whites, only ladies and gentlemen.’” Although it was illegal to hold interracial meetings, she was not intimidated by the legal system and did what she felt was right. At any given time during Sunday meetings, wealthy doctors and lawyers sat beside affluent, middle-class and poor members of the black community. Although some may have been in shock initially, eventually it became accepted that if you were going to participate in Bethune’s meeting, you would do so by her rules. This simple action made her school a place of protest that went directly against the Jim Crow policies and procedures permeating America.

For those who remembered Sunday Community Meetings, they were well-attended and well-known events, and their popularity spread to the beachside tourists of Daytona Beach. Although it was rare for whites to cross into Midtown, they came to attend B-CC’s Sunday afternoon event. The students, faculty and staff of the college and the local community attended and performed during the meetings. It was a time when people of all colors congregated, and all eyes were on the children of Midtown. In an interview, Mr. Harold V. Lucas Jr. fondly remembers the meetings, which he attended starting in 1939:

Sunday community meetings…well, first of all, you know there were not supposed to be any interracial groups meeting during this time. I remember community meetings from the time I was like seven or eight years old. What they would do was they would again have the concert choral type people, they would sing and we would have a program where they would talk about different things about the school. They didn’t talk about issues; it was not that type of community meeting. What it was…it was a thing where white people and black people could come and enjoy music and enjoy little kids speak. And I remember the first time that I went to community meeting, and I was supposed to say my little speech and I had practiced it, you know. And I got up on the stage, and you’d stand behind the curtain; then they would open the curtain and you’d step out; and then you’d say whatever you had to say; then you’d go back behind the curtain. And when it was my time, I looked out there and said, “It’s too many people.” And I went back behind the curtain, and my daddy said, “No, go out there and say your speech.” But the community thing was an attraction that helped to draw the people that might be interested in helping Bethune to the campus so that they could see what she was doing. And that’s how Mr. Gamble and Mr. Rockefeller and Mr. White and how those people became…“Well, what is this?” They came looking for something to do. You know, they were just down here in this nice sunny weather and they didn’t have anything to do on Sunday afternoons ‘cause you know they didn’t have TV and all of that stuff. “We’ll go over there and hear those black folks sing and hear the little kids. And what’s the lady’s name over there that’s trying to start that school?” You know they were inquiring about what was going on here because the people that she had met on the beachside were the main people that ran the community, and she convinced them. And of course you know if John D. Rockefeller was coming over here…the Proctor and Gamble man was coming over here, all his little cronies was wondering, “Well what are you going over therefor?” and then they would say, “Oh man they can sing and they have little kids doing stuff and you ought to see how they are improving those grounds over there.” Again improving the grounds was an element of the whole thing.

Sunday Community Meetings. Courtesy of the Bethune-Cookman University Archives.

In Mr. Lucas’s memories of the meetings, he notes that political issues were not discussed; however, the meeting in itself was a political statement. A powerful figure like Mary McLeod Bethune didn’t necessarily need to stand in a picket line to protest; rather, she used the place that she had ownership of—an institution of learning—to stand firm against injustice. She also allowed all of Daytona Beach and beyond to witness the jewel of performing arts and creativity that flowed throughout the community, and she was able to use that to gain necessary funding for the school. As a businesswoman, she was well aware of the wealth that the beach town generated, and she was able to shift tourism to an area of town where it was least expected. Throughout her lifetime, she continued to take a stand against the discriminatory nature of segregation. Her secretary, Mrs. Senorita Locklear, with whom she worked from 1954 to 1955, remembers Bethune’s story of how she took a one-hour ride to the segregated Municipal Auditorium in Orlando to hear a noted spe...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword, by Warren Cooper

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Welcome to Frenchtown

- Part I. $1.50, Faith in God and Five Little Girls: The Founding of Bethune-Cookman University

- Part II. Maintaining the Legacy of Mary Bethune at the Bethune Foundation Historic Home

- Part III. White Sands, Black Beaches: The Beginnings of Historic Bethune Beach

- Part IV. A Mother, a Friend and a Boss Lady: The Inner Circle of Mrs. Bethune

- Part V. Galvanizing Women for Change Across the Sunshine State

- Conclusion: The Last Words of a Legendary Woman

- Bibliography

- About the Authors