- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

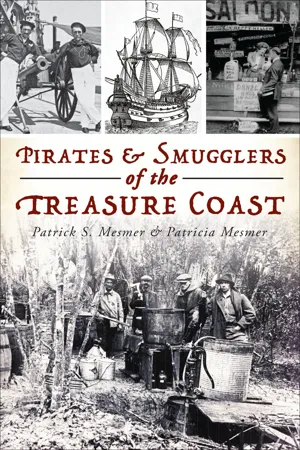

Pirates & Smugglers of the Treasure Coast

About this book

Discover the outlaws who have made—and lost—fortunes along the Florida coast over the centuries . . .

For hundreds of years, colorful characters and criminals used the myriad coves and inlets along the Treasure Coast for illicit commerce. From the early days of privateer Henry Jennings to the notorious Prohibition exploits of the Ashley Gang, these sandy shores have been a refuge for those looking to trade on the dark side of the law.

Legendary tales of Don Pedro Gibert, Spanish Marie, and Al Capone all contribute to the lore of a region that is home to buried treasure and family crime empires. Join historians Patrick and Patricia Mesmer on a journey through the Sunshine State's shadowy past, including photos and illustrations.

For hundreds of years, colorful characters and criminals used the myriad coves and inlets along the Treasure Coast for illicit commerce. From the early days of privateer Henry Jennings to the notorious Prohibition exploits of the Ashley Gang, these sandy shores have been a refuge for those looking to trade on the dark side of the law.

Legendary tales of Don Pedro Gibert, Spanish Marie, and Al Capone all contribute to the lore of a region that is home to buried treasure and family crime empires. Join historians Patrick and Patricia Mesmer on a journey through the Sunshine State's shadowy past, including photos and illustrations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pirates & Smugglers of the Treasure Coast by Patrick S. Mesmer,Patricia A. Mesmer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Ancient Residents

In 1565, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés landed at the future site of St. Augustine, Florida, where he encountered the great Timucua people. Menéndez was there to remove a French colony of Huguenots who, two years prior, had settled about twenty miles to the north near the mouth of the St. Johns River at a place they named Fort Caroline. Already familiar with Europeans and their strange customs due to their previous interaction with the French, the Timucua were understandably suspicious of these newcomers. At first, relations with the Spanish were amiable, but things quickly degenerated as the natives realized that the newcomers were not leaving. The Timucua were a very powerful people but, in the long run, proved to be no match for Spanish guile, vicious brutality, powerful weapons and deadly European diseases.

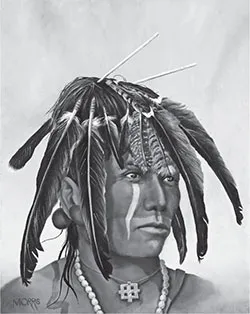

To the south of their domain, starting near today’s Daytona Beach, was an area designated as the “Land of Ais” on old Spanish maps. These Ais, or Ayz people, depending on which Spanish map from that period you use as a reference, proved to be a formidable foe of the Spanish for the next two hundred or so years. These were the original inhabitants of the area known today as the Treasure Coast. A strong and fiercely dominant people, the Ais resisted European conquest with great zeal. The Spanish never had enough manpower to properly police the entire east coast of La Florida or to dominate the numerous Ais, so the two sides maintained a reluctant alliance for many years. In addition to fish and game, they ate oysters, clams and snails from what is today called the Indian River. The Spaniards referred to the river as the Rio d’Ays on all their maps. The Seminole people called it the Aysta-chatta-hatch-ee, or the “River of the Ais Indians.”

High Counselor. By artist Theodore Morris.

The Ais were not what one would call an agricultural people, nor were they nomadic. Gatherers or foragers would be a more accurate description. The coastal settlements had such an abundant and stable food supply that they simply didn’t have to work very hard to feed themselves. A wide assortment of fish and small whales, oysters, clams, small animals, birds and edible plant life were so plentiful that it only took a short time each day to sustain a very healthy diet.

How could the Ais Indians stand to live in the hot, mosquito-ridden environment of Southeast Florida? To answer this question, it is important to remember that most of our ancestors of European descent have only lived in Florida for a maximum of about five hundred years, with a huge surge in population since the advent of air conditioning. The Ais, Timucua and many other native tribes lived here for thousands of years. It boggles the mind to comprehend such time spans. These people were perfectly adapted to life in the South Florida environment. The weather patterns would have been like those of today. In the winter months, they would maintain their coastal settlements to fish and reap the benefits of the ocean on the barrier islands. When the summer months came, with waves of exhausting heat, hurricanes and hordes of insects, the Ais would retreat to their mainland settlements. They simply knew no other way of life. For this reason, they flourished and multiplied along the coast for many centuries. Whole cultures lived, laughed, cried, found lovers, had babies, worshipped their gods and died there. The Ais were so numerous that, when the Spanish arrived in the late sixteenth century, the newly appointed governor stated that he had never seen so many people. Many of their burial mounds and garbage middens (the ones that have not been destroyed by development) can still be found, if one knows where to look.

FLORIDA’S FIRST PIRATES

One of the activities that the Ais indulged in was piracy and kidnapping for ransom. At that time in history, the area of the Caribbean that ran from Cuba northward along the eastern Florida coast was known as the Bahama Channel. This route was heavily used by wind-borne shipping vessels for hundreds of years due to the natural three-knot currents of the Gulf Stream. The Bahama Channel was the most popular shipping lane of the time, especially for the great treasure galleons that made their way north laden with treasure that had been plundered from Mexico, South America and Asia. If they were traveling south, they would have been forced to avoid the natural northern current of the Gulf Stream by sailing inside the channel, even closer to shore. To avoid this, they had to sail on a long, roundabout journey that spanned thousands of miles. During the height of the Spanish conquest and plunder of South America, the hulking treasure galleons began their journey in Seville, Spain (later from Cadiz), and sailed down the coast of Africa to the Canary Islands, where they stopped for supplies. They then turned west to take advantage of the trade winds and, after sailing about a month or more, entered the Caribbean southeast of Puerto Rico. Here the convoy split into two: the Tierra Firme (Spanish name for the South American mainland) and the New Spain Fleets. After their holds were full of treasure and goods, they would rendezvous at Havana, Cuba, then the center of the Caribbean world. The ships would then leave in groups known as flotillas as a safeguard against piracy, taking advantage of the northern currents of the Gulf Stream to get back to Europe. This route took them along the coast of La Florida, near the wild, desolate coastal lands of the Ais, for hundreds of years.

The native people grew to resent the cruel, indifferent treatment of the Spanish invaders, so they gradually learned how to fight back. They quickly realized that the Spaniards had a great weakness for the chests full of gold and silver coins that filled the holds of the mighty galleons. The region has always been a magnet for hurricanes, so there were frequent shipwrecks along the coastline of their domain. When violent storms would rage across the Atlantic, unsuspecting vessels would often meet their end in the horrific winds and high seas. Despite the valiant efforts of the experienced seamen, these raging tropical cyclones would slowly push the wooden ships toward the shoreline, where the shallow, jagged reefs would tear their hulls to splinters. In the sixteenth century, the area now known as the Treasure Coast was a forbidding place to be shipwrecked. The low vegetation provided no cover from the brutal sun, and the voracious black clouds of mosquitoes and sand flies were maddening. Black bears posed a viable threat, especially during sea turtle nesting season, as they aggressively searched the beaches for the delicious eggs buried in the nests. Panthers were also prevalent, even on the barrier islands. Besides these dangers, the unfortunate soul who found himself stranded in this lonely, desolate paradise would face death by exposure, thirst or hunger.

The Ais and their subtribe to the south, the Jeaga, learned early on that prisoners taken from these shipwrecks could be exchanged for goods or Indian prisoners held captive by the Spanish. When a galleon wrecked on the reefs, the Ais would descend on the wreck in great screaming numbers, mercilessly slaughtering or enslaving the exhausted, terrified survivors and robbing the unfortunate vessel of any treasure. They would then carry whatever booty they had plundered back to their villages and bury it near the home of their leader, the Casseekey, for safekeeping. Captured survivors were often treated as currency, as they were shifted from village to village until the Casseekey could find the best deal for a trade. For these reasons, the Ais were known as the wealthiest tribe in the Americas at that time.

PEDRO MENÉNDEZ DE AVILÉS, 1565

After annihilating the French at Fort Caroline and establishing the fledgling colony of St. Augustine, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés took a tour of the Ais villages to the south. He had heard many tales of these fierce people and wanted to see them for himself. As he walked through one of these native settlements, he was shocked to see a white man among them. He was even more surprised when he heard the man’s story. Eighteen years earlier, a Spanish merchant ship had wrecked on the coast near the village. The unfortunate survivors had been spilled out onto the hot sand with no water, food or any other necessities. The Ais warriors then attacked, brutally killing everyone except the one man. The reason they spared him was that he was a silversmith. The Ais warriors, vain about their appearance, treasured the earrings and pendants that the man could fashion. As the years passed, the white man gave up any hope of being rescued and eventually acclimated into the tribe, even taking a wife and having several mixed-race children. Even though the attack had occurred so many years’ prior, Menéndez’s temper brewed at the audacity of this violent attack on his countrymen. As he continued his tour of the Ais settlements, he secretly devised a plan for revenge. Back at the village where the Spaniard had been imprisoned, he announced that there would be a great celebration of unity. He and several of his soldiers entered the village, each taking a place next to an Ais warrior. At the height of the gathering, Menéndez stood and gave the prearranged signal, clapping his hands three times. Each one of his men then quickly pulled knives and swords, viciously stabbing the surprised, unsuspecting natives to death before they realized what was happening. Thus, began the gradual subjugation and cruel treatment of the indigenous tribes of South Florida.

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés. Public domain.

TERRIFYING STORY, 1570

There was a story that swept through Caribbean ports that sent a chill of fear through any traveler who heard it. In 1570, a ship owned by a Spaniard named Alonso Centeno was transporting tons of animal hides from South America to Seville. His crew numbered thirty-five, with a few women and children onboard. As the vessel traveled up the Bahama Channel along the east coast of Florida, it was intercepted and captured by English pirates. The pirates took the passengers and crew to a barrier island known today as Jupiter Island, promising them that the local Jeaga Indians would not harm them due to an alliance with the Spanish. The native warriors greeted these unfortunate souls with open arms. What is interesting about this story is the relationship between the English pirates and the Jeaga Indians. Delivering their unfortunate Spanish captives to the natives would be a “win-win” for the pirates because they could conveniently get rid of any witnesses to their crimes. The Indians, on the other hand, placed a high value on captives, especially Spanish ones. They could trade their slaves with other tribes, like the Ais to the north or the mighty Calusa to the west. Prisoners were valuable bargaining chips.

For some unknown reason, the Jeaga chose a different path regarding these new prisoners. As soon as the pirates disappeared over the horizon, they fell on the Spanish captives with a vengeance, immediately hacking thirty men to pieces. The only lives that were spared were those of a young mother, her two daughters, her son and a sailor who was so badly wounded that he was near death. A short time later, Pedro Menéndez, nephew to the great conqueror Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, came to the area on a mission for his uncle. He was shocked to see the haggard surviving captives with the natives. Realizing that he did not have the manpower to overpower the mighty Jeaga, he offered to purchase these poor souls for the price of twenty ducats. The natives refused. Menéndez then used the Indians’ own tactics against them. He traveled north to a nearby Ais settlement and captured six warriors. He then returned to the village and traded them for the prisoners.

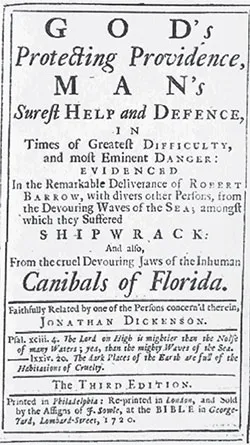

JONATHAN DICKINSON, 1696

In 1696, the barkentine Reformation encountered bad weather off the coast of present-day Jupiter Island. Onboard was a Quaker by the name of Jonathan Dickinson who was en route from Jamaica to Philadelphia with his young wife and infant son. The vessel was shipwrecked on the island, all twenty-two souls left destitute on the wild coastline. They were discovered by two Jeaga warriors, whose frightening appearance and threatening gestures terrified the party. For whatever reason, the Indians chose to spare the bedraggled survivors, instead taking them prisoner. They then herded the Dickinson party approximately five miles south along the beach to a huge settlement on present day Jupiter Inlet:

About the eighth or ninth hour came two Indian men (being naked except a small piece of platted work of straws which just hid their private parts, and fastened behind with a horsetail in likeness made of a sort of silk grass) from the southward and running fiercely and foaming at the mouth having no weapons except their knives, and forthwith not making any stop; violently seized the first two of our men they met with who were carrying corn from the vessel to the top of the bank, where I stood to receive it and put it into a cask. They used no violence for the men resisted not but taking them under the arm brought them towards me. Their countenance was very furious and bloody. They had their hair tied up in a roll behind in which stuck two bones shaped one like a broad arrow, the other a spearhead. The rest of our men followed from the vessel, asking me what they should do whether they should get their guns and kill these two; but I persuaded them to be quiet, showing their inability to defend us from what would follow; but to put our trust in the Lord who was able to defend to the uttermost. I walked toward the place where our sick and lame were, the two Indian men following me. I told them the Indians were come and coming upon us. And while these two (letting the men loose) stood with a wild, furious countenance, looking upon us I bethought myself to give them some tobacco and pipes, which they greedily snatched from me, and making a snuffling noise like a wild beast, turned their backs upon us and run away. —Jonathan Dickinson, God’s Protecting Providence, 1699

“The Florida Indians Capture the Shipwrecked Company,” from Pieter van der Aa, 1707. Florida Memory Blog September 13, 2013.

Jonathan Dickinson’s journal cover, 1720. Public domain.

After a month, Dickinson and most of his party would eventually gain release from the Jeaga. The miserable party then began a torturous 230-mile trek north, slowly plodding along the beach all the way to the Spanish settlement of St. Augustine, Florida. They had very little clothing or supplies, so they were completely exposed to the elements. It was winter, so the farther north they traveled the colder it got. They also had to endure constant harassment by the Indians of several native settlements they passed for almost the entire journey. The journey was so harrowing and the hardships so great that several members of the party perished along the way. They were then rescued by the Spanish, who then sent them on to Charles Town (Charleston) in the colony of South Carolina. They later made it to Philadelphia, where Dickinson recovered and prospered. He went on to become mayor of Philadelphia twice, from 1712 to 1713 and again from 1717 to 1719. During those years, he wrote a detailed journal documenting his adventures in the wilds of Florida. Today, this short book contains the best description of the native people of the Treasure Coast that we have.

AIS TREASURE

There were thousands of shipwrecks along the Treasure Coast over a span of hundreds of years, many of them carrying vast amounts of treasure from places like Havana, Peru and Mexico City. The Ais wreckers were always there and became proficient at raiding these wrecks and absconding with any of the salvaged treasure. What they did with all of it is still up for conjecture today. It is well known that the Ais Casseekeys often had the loot secreted in great caches near their burial mounds in the forests of Southeast Florida for safekeeping. Sir John Hawkins (1532–1595) was an English slave trader who was among the first to profit from the “triangle trade” of goods and African slaves. John Sparks, chronicler of Hawkins’s voyages, wrote about the riches of the Ais:

Gold and silver they want not, for the Frenchmen who first came here had the same offered to them for little or nothing, and how they came of this gold and silver the Frenchmen did not yet know, but by guess, and having traveled to the south of Cape Canaveral they found the same dangers by mea...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. The Ancient Residents

- 2. The Treasure Coast Is Born

- 3. The Golden Age of Piracy

- 4. Don Pedro Gibert

- 5. Smuggling and the Slave Trade

- 6. Smuggling on the Treasure Coast, 1845–65

- 7. Florida’s Whiskey Pirates and Smugglers

- 8. The Notorious Ashley Gang

- 9. The Drug Trade on the Treasure Coast, 1960–Present

- 10. Pirates and Smugglers of the Treasure Coast Today

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- About the Authors