- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pirates of Colonial Newport

About this book

The stories behind the legends are revealed in this history of Colonial-era piracy and the double lives of those who sailed under the black flag.

The story of Newport, Rhode Island's pirates began with war, ended with revolution, and inspired swashbuckling legends for generations to come. From 1690 to the American Revolution, many of Newport's fathers, husbands, and sons sailed under the black flag. They sailed into foreign waters, t return home from plundering the high seas to attend church and even serve in public offices.

The citizens of Newport initially welcomed pirates with their exotic goods and gold to spend. But the community changed its tune when Newport's prosperous shipping fleet became a target of piracy in the early eighteenth century. The locals who had once offered safe haven were suddenly happy to cooperate with London's hunt for pirates.

In this authoritative history, author Gloria Merchant covers well-known pirates like Thomas Tew as well as surprising ones such as Thomas Pain. Merchant also explores pirate lore from Captain Kidd's buried treasure to the largest mass hanging of pirates in the colonies at Gravelly Point.

The story of Newport, Rhode Island's pirates began with war, ended with revolution, and inspired swashbuckling legends for generations to come. From 1690 to the American Revolution, many of Newport's fathers, husbands, and sons sailed under the black flag. They sailed into foreign waters, t return home from plundering the high seas to attend church and even serve in public offices.

The citizens of Newport initially welcomed pirates with their exotic goods and gold to spend. But the community changed its tune when Newport's prosperous shipping fleet became a target of piracy in the early eighteenth century. The locals who had once offered safe haven were suddenly happy to cooperate with London's hunt for pirates.

In this authoritative history, author Gloria Merchant covers well-known pirates like Thomas Tew as well as surprising ones such as Thomas Pain. Merchant also explores pirate lore from Captain Kidd's buried treasure to the largest mass hanging of pirates in the colonies at Gravelly Point.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pirates of Colonial Newport by Gloria Merchant in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Early American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Players

Colonial Newport’s docks spawned pirates, privateers and smugglers. It was often difficult to separate the three occupations.

Pirates

Pirates attacked everything from canoes to well-armed merchant ships. They did not, however, attack fellow pirates. International pirate crews considered themselves to be a brotherhood. They addressed one another as Brother Pirate and referred to themselves as Brethren of the Coast. Group loyalty led many to exact revenge on cities that executed their brethren by killing captains and destroying ships from those harbors. Pirates were violent, battle-hardened thugs. Images of them armed to the teeth with pistols, knives and cutlasses are no exaggeration. They lived hard, drank hard and died, for the most part, young.

Many sea rovers received their training and experience in either the Royal Navy or the merchant marines. They knew what they were doing. They also knew that life on a pirate ship was better than life on naval or merchant ships. Britain’s rigid class system extended its abuses to its naval and merchant fleet. Sailors drifted in from Britain’s lower classes while officers cruised in as sons of privilege. Discipline on board included brutal beatings that could result in disability or death. Officers ate and drank well, but the crew did not. Common sailors earned little and captains often withheld the crews’ wages to discourage desertion. Sailors routinely deserted and, occasionally, mutinied with piratical intent. Pirates blamed abusive captains and life in His Majesty’s service for their career moves as often as they blamed hard liquor.

The Buccaneer Was a Picturesque Fellow. Howard Pyle illustration. From Harper’s Monthly, December 1905.

Pirates governed themselves democratically and distributed plunder equitably. Crews voted on where to sail and what ships to attack. Crews also voted captains in or out of command. The captain’s authority was absolute only during battle. Captains shared sleeping quarters with their men and ate in the common mess. Pirates did not tolerate abusive captains. They would be voted out of office and marooned.

The workload for pirate crews was lighter than for merchant crews. In Under the Black Flag, Cordingly explained that twelve crewmen typically manned a one-hundred-ton merchant ship. Eighty or more pirates manned vessels of comparable size.

Since pirates could not easily purchase boats or fit out legally, they stripped captured vessels of everything useful, including guns, ammunition, rigging, tackle and sails. Pirates added desirable prizes to their fleet and burned or scuttled undesirable ships. Released prisoners might have been allowed to make their way home in their stripped vessel. Pirates often stripped prisoners as well. Gentlemen of fortune had an eye for fine clothing.

Pirates fought to the death to avoid capture but preferred that their prey surrender with a minimum of violence. Once the Jolly Roger was hoisted, they relied on their ferocious reputations and superior numbers to intimidate the opposition. Aside from not wanting to risk injury or death, pirates did not want to damage the vessel under attack. A sunken prize was of no value, and a badly damaged ship could not be added to their fleet.

Treatment of prisoners ranged from civil to sadistic. Pirates treated a ships’ captain according to how well the captain treated his crew. Prisoners who offered little or no resistance could be allowed to sail away unharmed. If the prize was hard won, its surviving crew risked being slashed with cutlasses, tortured and/or murdered. Particularly brutal treatment, including the cutting off of ears, lips and noses, was used to force prisoners to reveal the location of treasure.

Pirates always invited prisoners to join their crew. Many voluntarily signed the ship’s articles, rules governing conduct, compensation and punishment. Men who possessed valued skills, such as doctors, carpenters and coopers (barrel makers), would be forced to join. Musicians would also be forced. Pirates enjoyed entertainment, plus, drumming and horn blowing during battle helped to demoralize the opposition.

Pirates often referred to themselves as privateers. The job description was partially the same: attack merchant ships and steal their cargo.

Privateers

Between 1652 and the American Revolution, England was at war more often than it was at peace. The Royal Navy could not spare men of war to defend the colonies and disrupt enemy commerce along the Atlantic coast. It needed privateers.

England and its enemies commissioned privately owned, armed vessels to augment their navies. The practice expanded their fighting fleets for free. It was a win/win for warring nations. What was in it for the privateers? Money.

Privateers brought captured enemy warships and commercial vessels into port to have them condemned as legitimate prizes by an admiralty court. The terms of the commission determined how proceeds from the sale of a vessel and its contents would be divided. Captains, crews, owners and the Crown received a percentage of the total. Captains and crews did not receive a salary. If they failed in their commission, they worked for free: no prey, no pay.

In order to obtain a privateering commission in England’s colonies, a ship’s captain requested a letter of Marquee and Reprisal1 from a colonial governor. That document, acquired for a fee, defined the purpose and duration of the commission. It also stated what percentage of the income would be received by the privateer’s captain, crew, owners and the Crown. Colonial governors could accept gifts but not a share of profits.

Money could be made even if privateers played by the rules, but fortunes could be made if they broke the rules. Privateers occasionally attacked merchant ships not at war with England. Some captains received privateering commissions to provide a veneer of legitimacy to piratical activity. Both practices dressed pirates in privateers’ clothing.

A notorious example of a privateer who broke the rules was Newport’s native son Thomas Tew. Captain Tew’s first privateering commission was granted in good faith. His subsequent commission was obtained despite the fact that everyone knew he intended to go a-pirating in the Red Sea.

Colonial governors often granted commissions knowing that the captain had no intention of privateering against the enemy. Captains, crews and ship owners divided plunder from neutral shipping. Sponsoring governors and their colonial governments received gifts or bribes. No one arrested the privateers for piracy, but they were pirates.

Smugglers

Colonial smugglers avoided taxes and imported goods illegally. In 1651, London passed the first of a series of Navigation Acts designed to enrich Britain at the expense of everyone else, including its colonies. Colonial America viewed London’s trade restrictions as obstacles to be overcome, not laws to be obeyed. The colonies relied on their merchants to sabotage Parliament’s efforts to legislate and tax them into submission. Newport’s merchants met the challenge.

Throughout the colonial period, Rhode Island merchants devised elaborate schemes to circumvent the law, evade London’s taxes and bring illegally obtained English, West Indian and European goods into the colony. Smuggling occasionally involved open acts of piracy, privateers’ selling goods embezzled from their prizes and acquiring plunder from pirates. Two Newport merchants, Benjamin Norton and Joseph Whipple, outfitted a brigantine for trade but ended up consorting with pirates instead.2

The demand for affordable European manufactured goods, as well as molasses for the production of rum, and the desire for profit led to colonial smuggling. Abusive tactics by the captains and crews of England’s enforcement ships drove Newporters to attack them—acts of piracy that incurred London’s wrath.

2

Newport’s First Privateers and Pirates

A conniving bully, an opportunistic soldier of fortune and a marauding bigamist became Newport’s first privateers. They were also the town’s first pirates.

The Dutch War

Maritime trade was the spark that ignited war between England and Holland in 1652. Rhode Island was vulnerable. An English settlement occupied eastern Long Island, and the Dutch occupied western Long Island. London directed the colony to defend itself.

The colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations had two general assemblies for a short time in its early history: the Mainland Assembly included the towns of Providence and Warwick, while the Island Assembly included the towns of Newport and Portsmouth on Aquidneck Island, which was called Rhode Island. The Island Assembly organized an admiralty court to issue privateering commissions and condemn enemy prizes.3

Edward Hull, Captain John Underhill and Thomas Baxter obtained privateering commissions. Newport should have chosen more wisely.

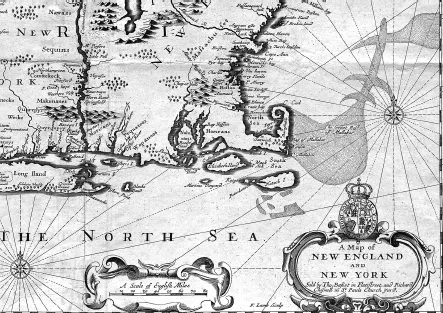

Map of New England and New York detail by John Speed, 1676. Courtesy of the Redwood Library & Athenaeum, Newport, Rhode Island.

Edward Hull

When Edward Hull learned that a war between England and Holland was imminent, he captured a Dutch vessel and hid it in one of Narragansett Bay’s coves. After war was declared, Hull secured a privateering commission and brought his prize into Newport Harbor. The ship was condemned by Newport’s admiralty court, but the Dutch captain sued. He proved that Hull acted in haste, and the decision was overturned and the captain awarded full compensation.

Hull’s next seizure belonged to Thomas Baxter, another Newport privateer. Hull defended himself valiantly, if offensively, before a New Haven court. When the magistrates threatened to send Hull to London to see what Parliament thought about his privateering, Hull realized the error of his ways and promised to behave.

The privateer was, apparently, incapable of behaving, however. Hull’s final capture, a French vessel, had nothing to do with the war against the Dutch.

Captain John Underhill

Captain Underhill sold his mercenary services to Massachusetts Bay Colony and the Dutch Colony of New Netherland. Both governments found reason to banish him. He moved to Newport, where he received a warm reception and a privateering commission.

Underhill’s single act as a privateer was to seize a Dutch West India Company trading post on the Connecticut River. He sold his share of the conquest over the objections of Connecticut’s general court. Newport realized no financial or military gain from Captain Underhill’s privateering.

The Canon Shot. Willem van de Velde the Younger, 1680. A painting of a Dutch man of war firing its canon. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Thomas Baxter

Peter Stuyvesant, Dutch director general of the colony of New Netherland, complained about English pirates attacking Dutch and English residents.4 Thomas Baxter commanded the pirates. After Baxter stole a barque owned by Samuel Mayo of Plymouth County, Connecticut ordered his arrest. Baxter eluded capture, continued privateering and created more enemies than friends.

Baxter’s theft of a canoe belonging to a Connecticut magistrate was the last straw. A second order for his arrest caught up with him. His capture caused the only recorded casualties of the Dutch war in New England. Baxter’s crew learned where he was held and assaulted the guards. One of Baxter’s men was killed, and an officer was wounded in the rescue effort.

Baxter’s privateering ended, but his legal problems did not. His wife claimed he had another wife in England and sued for divorce. Afterward, Bridget Baxter’s ex-husband disappeared from her life and Newport’s history.

The End of the First Dutch War

Newport’s privateers proved to be more trouble than they were worth. The Dutch West India Company demonstrated admirable self-restraint by choosing not to attack those “pirates” out of Newport.

3

Newport’s Own Thomas Tew

Thomas Tew was well born, well connected and anything but well intentioned. His business partners included Governor Fletcher of New York, pirate patron, and Captain John Avery, arch-pirate.

In its September 19, 2008 article “Top-Earning Pirates,” Forbes magazine ranked Tew third after Sam Bellamy and Sir Francis Drake. Tew’s wealth, estimated at $103 million, was well above Blackbeard’s modest $12.5 million.

Native Son

Tew was related to a respected Newport family. One ancestor is listed in the colony’s charter of 1663. Another family member became Newport’s deputy governor in 1714. Thomas’s father, also named Thomas, was probably a mariner.

Tew Goes A-Privateering

Tew arrived in Bermuda in 1691 with ambition backed by gold. He purchased a share in the sloop Amity. It was common knowledge that Tew had sailed on the account, a reference to piracy. That reputation was probably an asset to his résumé.

King William’s War set Tew on a course of plunder and profit. In 1693, Bermuda’s lieutenant governor issued a privateering commission to Tew and another captain to destroy a French factory off the African coast. When a violent storm separated both sloops, the Amity’s captain decided to change course...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. The Players

- 2. Newport’s First Privateers and Pirates

- 3. Newport’s Own Thomas Tew

- 4. Captain Thomas Paine

- 5. Captain William Kidd

- 6. Wicked and Ill-Disposed Persons

- 7. Red Sea Pirates Wash Ashore

- 8. A Nest of Pirates

- 9. Newport’s Last Pirate Captain

- 10. Muddy Waters

- 11. The Tide Turned

- 12. Stretching Hemp for Pirates

- 13. Ship’s Articles

- 14. The Jolly Roger

- 15. Church and State

- 16. Trinity Church

- 17. Pirates and Revolutionaries

- 18. Well-Told Tales

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- About the Author