- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Locomotives of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

About this book

The Liverpool & Manchester Railway was Britain's first mainline, intercity railway; opened in 1830 it was at the cutting edge of railway technology. Engineered by George Stephenson and his team – John Dixon, William Allcard, Joseph Locke – the project faced many obstacles both before and after opening, including local opposition and the choice of motive power, resulting in the Rainhill Trials of 1829. Much of the success of the line can be attributed to the excellence of its engineering but also its fleet of pioneering locomotives built by Robert Stephenson & Co. of Newcastle. This is the story of those locomotives, and the men who worked on them, at a time when the locomotive was still in its infancy. Using extensive archival research, coupled with lessons learned from operating early replica locomotives such as Rocket and Planet, Anthony Dawson explores how the locomotive rapidly developed in response to the demands of the first intercity railway, and some of the technological dead ends along the way.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Locomotives of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway by Anthony Dawson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Rail Transportation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

THE STEPHENSON LOCOMOTIVE

CHAPTER 1

From Rocket to Northumbrian

The success of Rocket at the Rainhill Trials of October 1829 resulted in the Board ordering four locomotives ‘on the principle of the ‘Rocket’’ from Robert Stephenson & Co on 26 October 1829; the Manchester Courier proudly announcing the purchase. But this should not be seen as a fait accompli for the Stephensons as James Cropper and his allies challenged the perceived Stephenson monopoly by, albeit unsuccessfully, promoting locomotives by Goldsworthy Gurney of London. At this date the Company had only four locomotives: Lancashire Witch, Twin Sisters, Sans Pareil (see Part 2) and Rocket. Of these, Lancashire Witch was on temporary loan from the Bolton & Leigh Railway, and where Sans Pareil was also on hire because it would not burn coke, eventually being sold to that line in March 1832. This left only Rocket and Twin Sisters, both of which were used on ballast and other permanent way duties: Twin Sisters at the Liverpool End and Rocket on the Chat Moss section. Edward Bury’s Dreadnought (see Part 2) was also reported to be at work on permanent way duties, probably on hire.

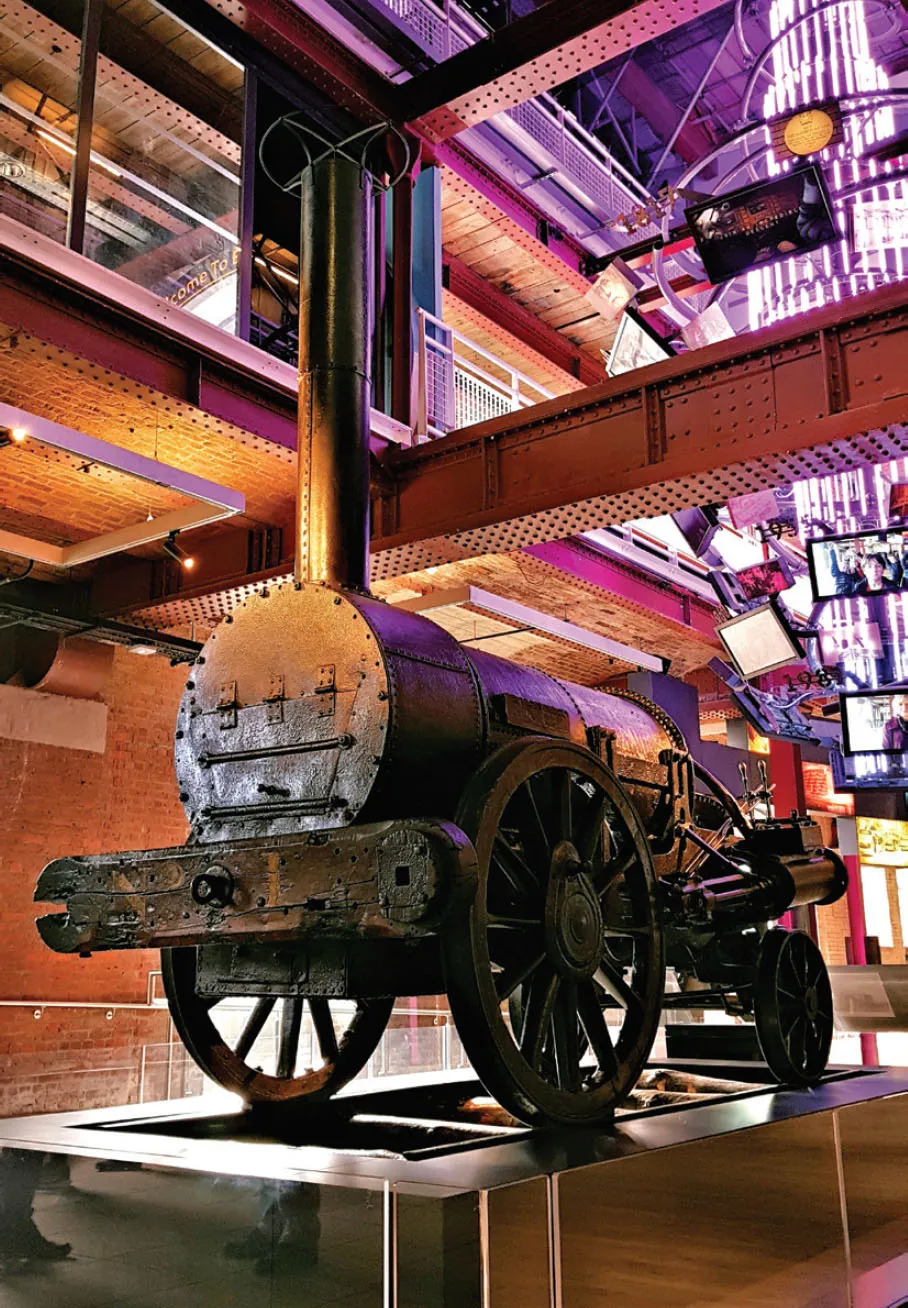

Origin of the species: Rocket (No. 1). Remains of the original Rocket returned to Liverpool Road station, Manchester, during 2018. (Ian Hardman)

Immediately after Rainhill, Rocket was used in a series of ‘public relations’ exercises, and on 19 October 1829 Rocket was put on the Chat Moss contract working ballast trains. It was on Chat Moss in November 1829 that a local publican, Henry Hunter, was killed when Rocket was derailed whilst propelling a train of ballast waggons. One of her carrying wheels broke on New Year’s day 1830 during experiments across Chat Moss, and a new pair was quickly substituted. The Press reported that the wheel which had broken had been ‘previously injured’ and the axle bent. Rocket was involved in yet another accident in February 1831 when one of her wooden driving wheels broke in Olive Mount cutting; the existing wheels and axles on the locomotive probably date from this accident. She was hired to the Wigan Branch Railway, and then subsequently laid up as a ‘stand by’ engine until 1833 when she was used as the test-bed for Lord Dundonald’s unsuccessful rotary steam engine.1

As soon as the next batch of locomotives were delivered, Rocket was obsolete; Rocket was in effect a proof of concept, rather than a production locomotive and underwent various in-service modifications to improve her operational flexibility, including provision of a buffer beam and lowering the cylinders during a very brief working life on the L&M. Edward Woods noted in the 1880s that ‘the Rocket was not frequently used, and rarely, if ever, in the service of the ordinary traffic on the line. It was, in fact, not sufficiently powerful for the service.’2

The next four locomotives were ‘production locomotives’, but were still in effect dynamic prototypes as lessons were still being learned by Robert Stephenson and his team at Forth Street during a frenetic 33-month period of locomotive development. Given the long absence of Robert Stephenson from Forth Street, it is likely much of the development was led by Phipps, the chief draughtsman, and William Hutchinson, the foreman. Indeed the Liverpool & Manchester Railway provided a ready test track which meant that the Stephensons could see their locomotives at work and modify them in the light of experience gained in operation.

These four locomotives incorporated: Henry Booth’s revolutionary multi-tubular boiler and a separate, water-jacketed firebox; cylinders with a direct connection to the driving wheels; and a blast pipe in the chimney. These new locomotives were not to exceed five tons in weight and were to be delivered in three months from the date of order. The Manchester Courier announced that with 90 boiler tubes these new locomotives would be ‘swifter, more powerful, and compact’ than Rocket. The first delivered was Wildfire aka Meteor, outshopped from Forth Street 7 January 1830 and tried in the yard at Forth Street ‘before a large party’ of gentlemen and their ladies; Comet followed on 21 January; Arrow on 4 February and Dart on 25 February. Wildfire and Comet had arrived at Liverpool by 1 February 1830, when they were duly named by the Board, who also ordered that trials be carried out to ‘ascertain the power of the Engine, and the quantity of coke consumed.’3

Evolution of the ‘Rocket Type’: Arrow delivered January 1830; North Star (August); Northumbrian (July) and Majestic (December) all drawn to the same scale, showing a gradual increase in size, and strengthening of the frames and cylinder mounting. (After Warren, 1923)

Wildfire made a spectacular debut:

‘The Cylinders are larger, and placed almost horizontally, and the diameter of the wheels is four inches greater … These alterations are expected to give the new engine greater speed, and to make its motion more regular and steady. There had also been an improvement made in means of stopping it, by which it may be brought to a stand still almost instantly … it exhibited a grand and imposing sight … and, as the engine was approaching its maximum velocity, it continued to vomit out from the top of the chimney sparks, and masses of blazing coke, which gave the machine the appearance of a moving volcano, scattering fire-balls and red-hot cinders as it darted along the road, illuminating the air and throwing a transient glare on the countenances of the astonished bystanders … aptly enough illustrated the name of “Wildfire” which is given to it.’4

In order to increase the heating surface in a boiler 6 feet long and 3 feet diameter, the number of tubes was increased to 88 of 2 inches outside diameter (those of Rocket were 3 inches)5, although other sources indicate 90 tubes (Meteor) or 92 tubes (Arrow).6 Cylinders were 10 x 16 inches (compared to 8 x 16½ of Rocket) and the valve chest was now on top of the cylinder; those of Rocket had been underneath due to fears of condensation or water being carried over. The wooden driving wheels had cast iron hubs, wrought-iron tyres and in lieu of wrought-iron crank ring, a wrought-iron strap supported the spherical crank pins. These wheels were 5 feet in diameter (those of Rocket were 4ft 8½ins) which would become the standard on the L&M, with two exceptions, until 1845.7 The use of 5 feet diameter driving wheels was inherited from the road coach tradition where experiments by General Desaguliers in the 1770s had shown that a 5 foot wheel was the optimum size at speeds from 10–12mph. Stability of the locomotive, especially at speed, was achieved through lowering the cylinders from 38º to 8º. The replica of Rocket has a pronounced ‘waddle’ because of the position of the cylinders, and a high centre of gravity. Experience from the replica suggests that the cylinder mounting plates flexed, and as a result keeping everything steam-tight became a major issue. Although stipulated to have a maximum weight of 5 tons, upon delivery Arrow was found to weigh 5 tons 14 cwt 2 qr. Rocket was subsequently modified to conform (where possible) with these later locomotives, including lowering and inverting the cylinders (January 1831) and provision of a smokebox (probably in February 1831). She was also provided with a front buffer beam to improve operational flexibility and the original somewhat flimsy bar frame strengthened with additional bracing. Arrow underwent trials in June 1830, organised by Hardman Earle. On the footplate with George Stephenson was Rev. William Scoresby FSA (1789-1857), scientist and arctic explorer, who timed the run. With a gross trailing load of 33 tons she ran from Liverpool to Manchester in 1 hour 46 minutes, having been assisted up the Whiston incline by Dart. She attained a maximum speed of 25mph.8 Meteor was involved in an accident when working in December 1830. As was the custom after dark, a Pilot Engine was run head, but it ran too far ahead of Meteor and her train. At Rainhill some platelayers attempted to cross the line with their lurry. Despite the Constable on duty waving his red lamp Meteor crashed into the lurry, and came off the rails and one wheel was broken. No passengers were hurt. Rocket which had been at work on ballast duties near by was used to take the train forward to Liverpool.9

Phoenix and North Star were ordered by the Board in February 1830; Phoenix was delivered in June 1830, and North Star in August, both costing £600.10 Both were larger than the four preceding locomotives; their boiler barrels were 6 inches longer and cylinders increased in size to 11 x 16 inches which would become the standard for the next few years. They also used ‘double slide valves’ whereas the early locomotives had used a single slide valve. Double slide valves would be standard practice until May 1832. The pair were also provided with a steam dome, steam riser and internal steam pipes to help prevent priming and to improve thermal efficiency; despite the 1979 replica of Rocket being so provided, provision of a steam dome etc. was a later modification in November 1830.11 Colburn (1871) states there were 90 copper tubes in the boiler, 2 inches diameter and 6 feet 6 inches long, providing a heating surface of 306 square feet; the firebox added a further 20 square feet. Phoenix was able to evaporate 41 cubic feet of water per hour, whereas Arrow could evaporate 34.4 cubic feet of water per hour. This larger heating surface meant Phoenix burned less coke per ton per mile than Arrow: 0.67lb compared to 0.78lbs.12 In order to ease maintenance, the pair were provided with the first proper smokebox – a forward extension of the boiler barrel, enclosing the blast pipe and end of the tubes, with a narr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART 1: THE STEPHENSON LOCOMOTIVE

- PART 2: BREAKING THE MOULD

- PART 3: ENGINEMEN AND FIREMEN

- PART 4: MAINTENANCE AND REPAIR

- PART 5: ROLLING STOCK

- Conclusion

- Select Bibliography

- Endnotes