![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Discovering Calleva

The most significant development in the history of investigations into the Iron Age and Roman town at Silchester was the great, 20-year long, project by the Society of Antiquaries of London to reveal what, at the time, was thought to be the complete plan of the town within its defensive walls. The excavations took place between 1890 and 1909, providing the first glimpse of the entirety of a Roman town in Britain and indeed of any town within the Roman world, even celebrated Pompeii. The town was confirmed to have been divided into regular insulae (Latin = islands), the great majority containing a number of buildings ranging from well-decorated private houses to modest shop or workshop premises, a few also with a temple or possible temple, one with a possible church, and the whole protected by the massive town wall. A few blocks were dominated by the public buildings they contained: the great forum basilica at the centre, dominating the town; the public baths at the lowest point of the town by the springs in the south-east quarter; the trio of temples in their enclosure by the east gate; and the inn with its attached bath house by the South Gate. The influence of the main thoroughfare, the east–west street which carried traffic between London and the west of Britain, can easily be seen in the crowding together, side-by-side, of narrow-fronted shops-cum-workshops competing for business along its length (Figs 1.1–2).

As we will see, there is a background of cumulative discoveries to this revelatory work, but it was a combination of factors which determined that Silchester was the first Roman town to be explored in this way. First and foremost it was a greenfield site only impinged upon by the parish church of St Mary the Virgin and the farm and farm buildings on its eastern side, but it was also in the single ownership of a sympathetic landowner, the Duke of Wellington, and the influential antiquarian society, the Society of Antiquaries of London, was keen to sponsor excavation. With large open areas within their walls, other Roman town sites offered similar potential: Aldborough of the Brigantes in Yorkshire, Caistor St Edmunds of the Iceni in Norfolk, Verulamium of the Catuvellauni beside St Albans in Hertfordshire and Wroxeter of the Cornovii, in Shropshire (Fig. 1.3). Across the River Severn in south-east Wales was the site of Caerwent, the chief town of the Silures, which, though the Roman town was partly buried beneath the village which had developed over it, followed Silchester to be the second most explored town of Roman Britain. Most of the other greenfield Roman towns saw substantial area excavations in the first half of the 20th century, but with none revealing more than parts of their whole town plan. Despite its shortcomings, as we shall see, the ‘complete’ plan of Roman Silchester has been published repeatedly through the 20th and into the present century and, as a consequence, arguably still remains the best-known Roman town in Britain. The background to the decision in 1890 to excavate Silchester can now be explored.

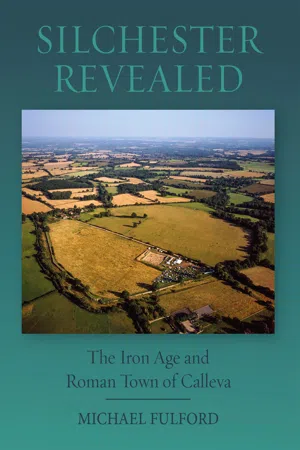

FIGURE 1.1 Aerial view of Silchester taken in 1976 looking towards the east, showing part of the Iron Age defences, the Roman street grid and outlines of some of the buildings (courtesy Chris Stanley)

Despite being shrouded in trees and vegetation, the impressive remains of its circuit of town walls, a mile and a half in length and enclosing a little over 100 acres (40+ hectares), had attracted antiquarians’ interest in Silchester since the 16th century. Among them was William Stukeley who visited Silchester in 1724 and, while recognising the amphitheatre for what it is, mistakenly depicted the town in the form of a rectangular military fort with its characteristic ‘playing card’ plan (Fig. 1.4). Although the outline of streets, which became visible each summer as the crop ripened, had been commented on by Camden in his great survey, Britannia, first published in English in 1610, it was the surveyor John Wright who was the first to attempt a systematic record of these and the town walls in 1745 (Fig. 1.5).

FIGURE 1.2 The plan of Calleva after the completion of excavations by the Society of Antiquaries within the town walls in 1908

FIGURE 1.3 Map of Britain showing the locations of the major Roman towns

Various accounts record digging taking place within the walls in the 18th and 19th centuries but with little information as to what was found. It was not until 1864 that excavations took place which were of a more scientific character, being recorded in some detail and eventually published in summary form. This was the work of the Reverend James Joyce, the rector of Stratfield Saye, who was encouraged by the second Duke of Wellington to undertake excavations, the manor of Silchester having been acquired by the first Duke in 1828. Joyce left two beautifully illustrated bound notebooks and a sketchbook, now in Reading Museum, full of information about the individual buildings and structures that his workmen had uncovered as well as about his methods of excavation (Fig. 1.6). While his work mainly laid bare the ground plans of the structures he found, it is clear that he also appreciated the importance of stratigraphy and how that could help him understand change over time and how to date buildings from independently dated objects, such as coins, associated with them. We see this, for example, in his interpretation of one of his most important discoveries, the forum basilica, the central building of the Roman town, which is understood to have accommodated administrative and judicial functions. Although Joyce and his team of four workmen excavated in several parts of the town within the walls, it is his work on the town gates, the forum basilica, the houses in Insula I and XXIII and the temple in Insula VII which are the most important, not least because they were published. His outstanding single find is undoubtedly the fine bronze ‘Silchester’ eagle which, along with other objects, was displayed in Stratfield Saye House, home of the Duke of Wellington (Figs 1.7, 3.18). These included a complete mosaic floor and fragments of two others which were lifted and re-laid in the entrance hall (Figs 1.8, 7.5). Excavation continued in a desultory way after his death, aged only 59, in 1878, including with the discovery of the large building and bath house near the South Gate which is very probably the mansio of the town. This was the accommodation reserved for officials and other users of the imperial posting service (cursus publicus).

FIGURE 1.4 William Stukeley’s illustration of the amphitheatre in 1724

FIGURE 1.5 John Wright’s plan of the town in 1745

FIGURE 1.6 Page dated 17 October 1870 from Joyce’s diary illustrating the fine copper alloy mount or handle known as the ‘Silchester horse’

(© READING MUSEUM (READING BOROUGH COUNCIL). ALL RIGHTS RESERVED)

FIGURE 1.7 The Silchester Eagle discovered by Joyce’s workmen in 1866. Made in bronze, it probably dates from the 1st century AD. It may have formed part of a statue of Jupiter or an imperial person, the eagle at the foot of the figure looking up

(PHOTO BY IAN CARTWRIGHT, © READING MUSEUM (READING BOROUGH COUNCIL). ALL RIGHTS RESERVED)

FIGURE 1.8 Second century mosaic from Insula I, House 1 discovered in 1864 and re-laid in the front hall of Stratfield Saye House

(PAINTING BY STEPHEN COSH, COURTESY OF STEPHEN COSH AND DAVID NEAL AND BY PERMISSION OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES)

Uncovering the town

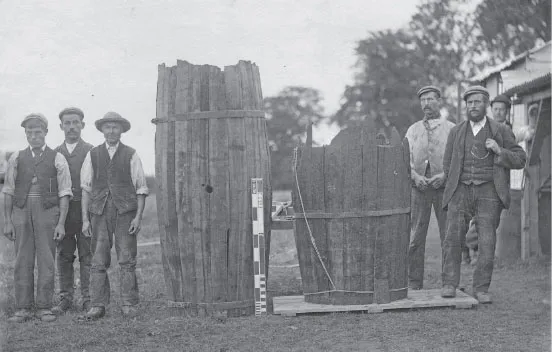

It was Joyce’s work which drew the attention of General Pitt Rivers, the first Government Inspector of Ancient Monuments, and the Society of Antiquaries of London to the remains at Silchester and the potential they had for revealing, for the first time, a complete plan of a Roman town. With the agreement of the third Duke of Wellington, a project began in 1890 sponsored by the Society of Antiquaries which was to last 20 years and was to reveal what was thought at the time to be the complete plan of the town within the walls. The excavation was directed by W. H. St John Hope, a senior official of the Society, and George E. Fox, an artist-architect and student of Roman Britain. Wherever possible the area was dug insula by insula with individual buildings identified by parallel narrow trenches dug systematically and diagonally across each one (Fig. 1.9). The insulae were individually numbered, the total amounting to 37 (Fig. 1.2). As wall foundations were discovered, they were followed to define the individual buildings which were then excavated to floor level (Fig. 1.10). The trenches were sounded for soft spots which might conceal the tops of pits or wells, which, on excavation, often turned out to contain well preserved artefacts, including items of organic materials such as the wooden barrels used to line the wells (Fig. 1.11), and two great hoards of ironwork, as well as very many examples of complete pots. There was methodological innovation, too, most notably by the geologist, Clement Reid, who, with his assistant, A. H. Lyell, recovered waterlogged seeds and insects from pits and wells each year from 1899 onwards. Reid identified a range of horticultural crops introduced by the Romans and grown in Britain, as well as traded items from the Mediterranean such as figs and grapes or raisins, though the latter could eventually have been grown locally.

FIGURE 1.9 Antiquarian excavation techniques: Left: plan of trenching across the north-east of Insula IX in 1893; right: geophysics detects traces of the Society of Antiquaries’ trial trenching across the whole town 1890–1908 (adapted from Creighton with Fry 2016, fig. 3.8)

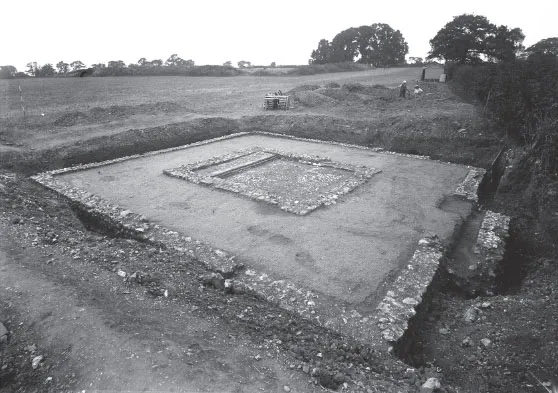

FIGURE 1.10 The temple in Insula XXXV excavated by the Society of Antiquaries in 1907. The spoil heaps from Joyce’s excavation of the forum basilica can be seen in the background

(©READING MUSEUM (READING BOROUGH COUNCIL). ALL RIGHTS RESERVED))

FIGURE 1.11 Imported wine-barrels of silver fir, subsequently re-used to line wells. Note the workmen and the scale.

(© READING MUSEUM (READING BOROUGH COUNCIL). ALL RIGHTS RESERVED)

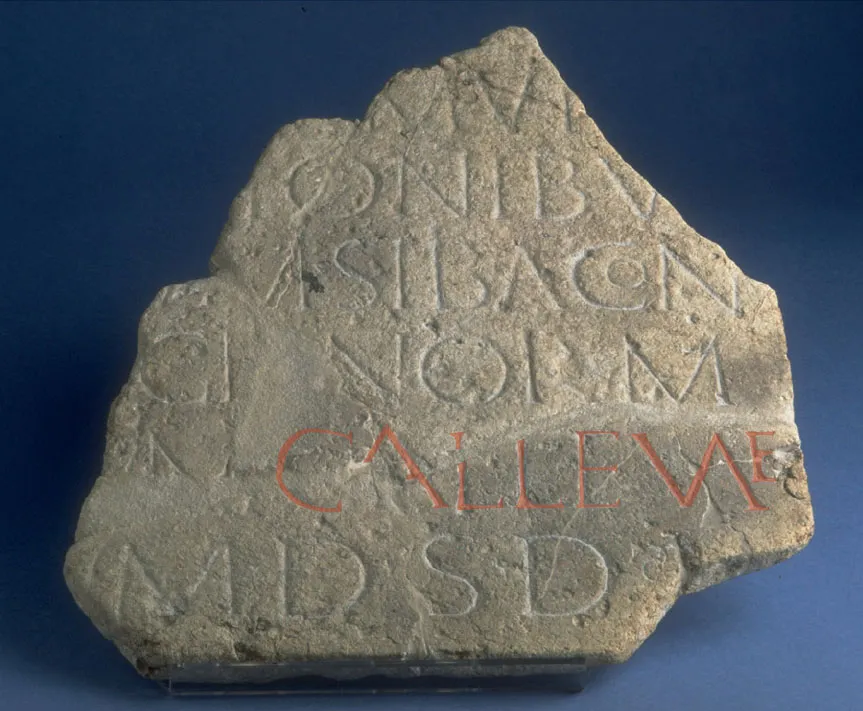

The year’s work was reported in the Society’s journal Archaeologia and included both overall plans of each insula and more detailed plans and descriptions of individual buildings and a summary of the more notable finds. Excavation within the walls was completed in 1908 and a final season of work took place the following year on the outlying earthworks and some Roman pottery kilns accidentally discovered to the north of the town. No excavation was undertaken on the amphitheatre and no attempt was made to locate extramural cemeteries. Over the years there had been much speculation as to the Roman name of the town, but this was brought to an end by the discovery in 1907 in a temple in Insula XXXV of an inscription carved on Purbeck marble recording a dedication by a guild (collegium) of foreigners (peregrini) confirming that the town was indeed Calleva, an identification first mooted in the early 18th century (Fig. 1.12).

FIGURE 1.12 Inscription carved in Purbeck Marble found in 1907 associated with the temple in Insula XXXV. It records a dedication which provides confirmation that Calleva was the ancient name of Silchester: CALLEVAE can be read in the penultimate line from the bottom

(© READING MUSEUM (READING BOROUGH COUNCIL). ALL RIGHTS RESERVED)

The excavations recovered a large number of finds, but by no means all were kept, particularly those of animal bone, building materials, whether of stone or brick, and pottery sherds, all of which were found in very large numbers (Fig. 1.13). Attention focused on rare finds, such as of sculptured fragments or inscriptions, and on metalwork, mostly of copper alloy, including coins, which are the most numerous find in this metal, but also well preserved ironwork. Complete or ...