- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

David Copperfield's History of Magic

About this book

An illustrated, illuminating insight into the world of illusion from the world’s greatest and most successful magician, capturing its audacious and inventive practitioners, and showcasing the art form’s most famous artifacts housed at David Copperfield’s secret museum.

In this personal journey through a unique and remarkable performing art, David Copperfield profiles twenty-eight of the world’s most groundbreaking magicians. From the 16th-century magistrate who wrote the first book on conjuring to the roaring twenties and the man who fooled Houdini, to the woman who levitated, vanished, and caught bullets in her teeth, David Copperfield’s History of Magic takes you on a wild journey through the remarkable feats of the greatest magicians in history.

These magicians were all outsiders in their own way, many of them determined to use magic to escape the strictures of class and convention. But they all transformed popular culture, adapted to social change, discovered the inner workings of the human mind, embraced the latest technological and scientific discoveries, and took the art of magic to unprecedented heights.

The incredible stories are complimented by over 100 never-before-seen photographs of artifacts from Copperfield’s exclusive Museum of Magic, including a 16th-century manual on sleight of hand, Houdini’s straightjackets, handcuffs, and water torture chamber, Dante’s famous sawing-in-half apparatus, Alexander’s high-tech turban that allowed him to read people’s minds, and even some coins that may have magically passed through the hands of Abraham Lincoln.

By the end of the book, you’ll be sure to share Copperfield’s passion for the power of magic.

In this personal journey through a unique and remarkable performing art, David Copperfield profiles twenty-eight of the world’s most groundbreaking magicians. From the 16th-century magistrate who wrote the first book on conjuring to the roaring twenties and the man who fooled Houdini, to the woman who levitated, vanished, and caught bullets in her teeth, David Copperfield’s History of Magic takes you on a wild journey through the remarkable feats of the greatest magicians in history.

These magicians were all outsiders in their own way, many of them determined to use magic to escape the strictures of class and convention. But they all transformed popular culture, adapted to social change, discovered the inner workings of the human mind, embraced the latest technological and scientific discoveries, and took the art of magic to unprecedented heights.

The incredible stories are complimented by over 100 never-before-seen photographs of artifacts from Copperfield’s exclusive Museum of Magic, including a 16th-century manual on sleight of hand, Houdini’s straightjackets, handcuffs, and water torture chamber, Dante’s famous sawing-in-half apparatus, Alexander’s high-tech turban that allowed him to read people’s minds, and even some coins that may have magically passed through the hands of Abraham Lincoln.

By the end of the book, you’ll be sure to share Copperfield’s passion for the power of magic.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access David Copperfield's History of Magic by David Copperfield,Richard Wiseman,David Britland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Photography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1 Secrets of the Conjurors Revealed

In the sixteenth century, witch hunters scoured Europe in search of those who they believed were dabbling in the dark arts. In 1584, one man spoke out against this toxic mix of superstition, fear, and ignorance. In doing so, he helped shape history and also produced the first book in the English language to present detailed descriptions of magic.

Born in the 1530s, Reginald Scot appears to have come from a relatively affluent family and to have spent most of his life in southeast England. Although little is known about his earlier years, many historians believe that Scot acted as a justice of the peace and had probably spent time studying law. In 1574 he produced a book on how to grow hops. Around a decade later he turned his attention to a much more serious and sober subject.

At the time, many people in Europe believed in the existence of witchcraft. According to this worldview, witches were able to summon evil spirits and to carry out various supernatural misdemeanors, including making people ill, rendering animals infertile, and causing crops to fail. These beliefs allowed self-proclaimed “witch hunters” to travel from town to town trying to eradicate this perceived threat to society. The late sixteenth century saw a surge in witch hunting across England and Scotland, with governments in both countries passing laws against witchcraft in 1563. Evidence of alleged wrongdoing often involved something as simple as an unusual birthmark, an unfortunate growth, or erratic behavior. Unperturbed, witch hunters and others extracted false confessions, encouraged unreliable eyewitness testimony, staged show trials, and were responsible for the deaths of hundreds of people. The majority of those accused were women.

Scot investigated the matter and in 1584 published his contentious conclusions in a book titled The Discoverie of Witchcraft. Containing over five hundred pages, Scot’s book displayed remarkable scholarship and drew upon the writings of more than two hundred other authors.

At a time when many people supported witch hunts, Scot bravely argued that these events were little more than the barbaric persecution of the vulnerable, old, and ill. His controversial text frequently proposed more rational approaches to these seemingly supernatural phenomena, arguing that those appearing to be witches might merely be superstitious or uneducated, that the effects of seemingly magical potions were due to chemical causes, and that those claiming to have been visited by nighttime demons were instead victims of a sleep disorder.

The Discoverie of Witchcraft was also the first work in the English language to present a detailed description of sleight of hand and conjuring. Several chapters of the book contained the secrets to illusions, including some principles that are still employed by modern-day magicians.

Scot’s book presented scientific and rational explanations for many seemingly supernatural phenomena.

Many of the illusions described by Scot relied on sleight of hand with balls, coins, and playing cards, including “To make a little ball swell in your hand till it be verie great,” “How to deliver out foure aces, and to convert them into foure knaves,” and the ever-popular “To make a groat strike through a table, and to vanish out of a handkercher verie strangelie.”

Other chapters explored the use of secret stooges and concealed verbal codes. For instance, Scot described how a conjuror might ask someone to go behind a door and arrange some coins into the shape of either a cross or a pile. The conjuror apparently listens to the sound of the coins clinking together and is able to reveal how they have been arranged. Scot revealed the secret of the illusion, noting that the person doing the arrangement of the coins was a confederate (“who must seeme… obstinatlie opposed against you”) and how they used a subtle verbal code covertly to convey the arrangement of the coins to the conjuror. (“What is it?” signifies a cross and “What ist?” a pile.)

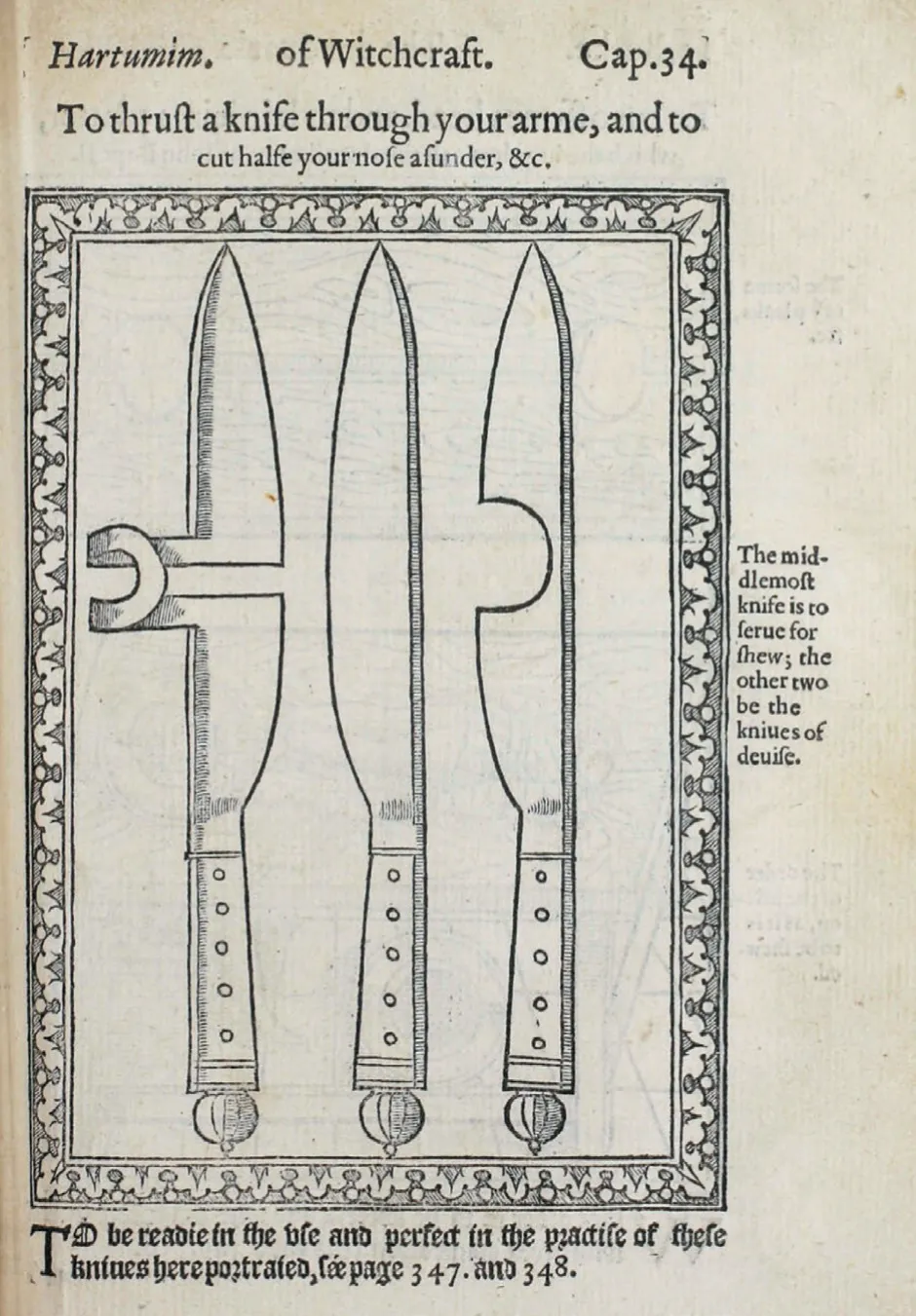

An illustration from The Discoverie of Witchcraft showing the apparatus that allowed performers “to thrust a knife through your arme, and to cut halfe your nose asunder.”

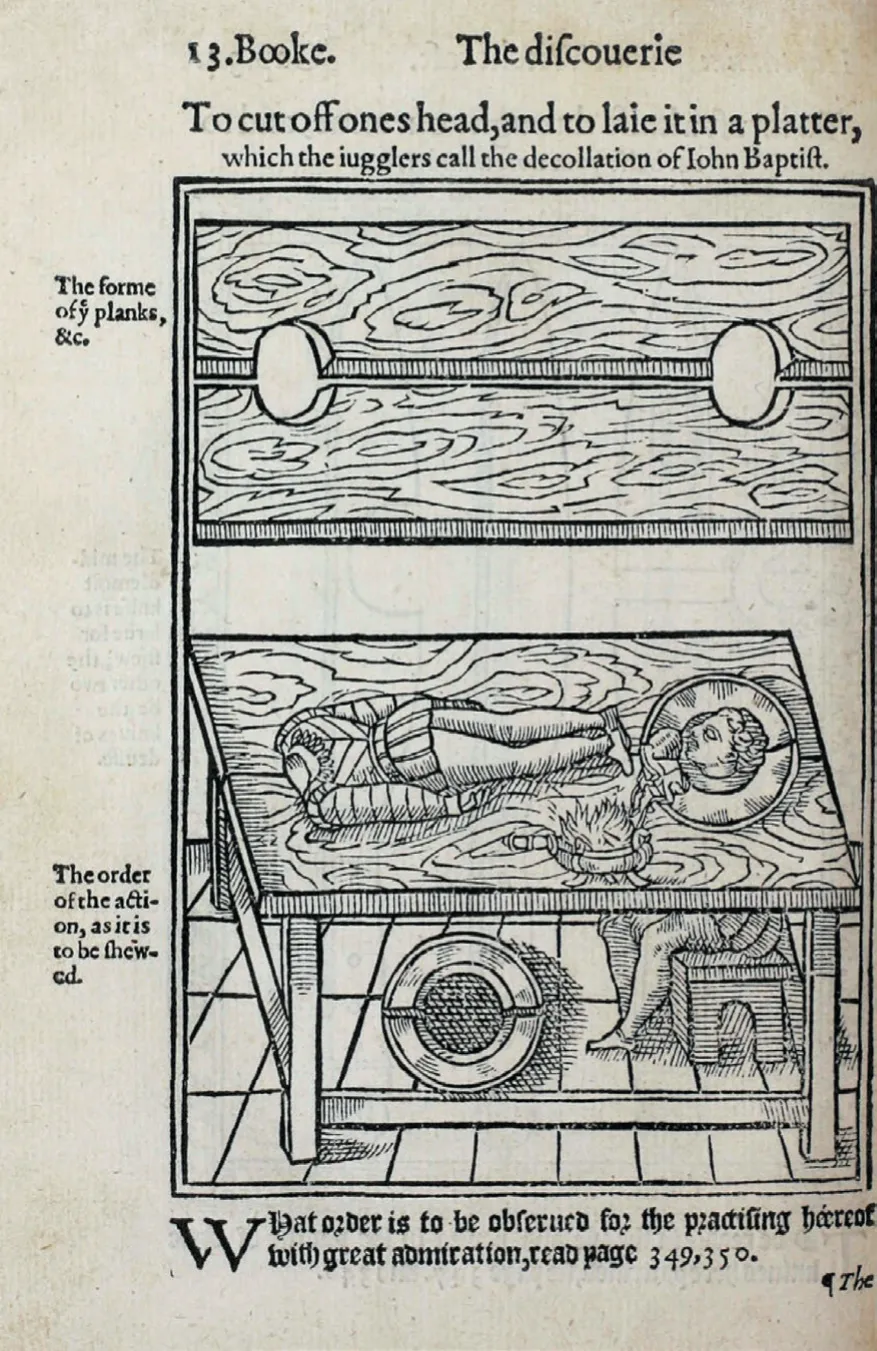

Scot explains how “to cut off ones head, and to laie it in a platter, which the jugglers call the decollation of John Baptist.”

Scot’s final chapters on conjuring discussed several illusions using boxes with false bottoms before moving on to more gruesome and shocking stunts, including how to appear to thrust a bodkin needle into your head, place a knife through your arm, stab yourself in the stomach, and cut off your head and lay it on a platter (“The decollation of John Baptist”). Once again, all of the secrets to these illusions were described in considerable detail and sometimes accompanied by vivid woodcuts. When it came to placing a bodkin needle through your head, for instance, Scot recommended the use of a bodkin with a retractable needle and a small sponge soaked in red wine (if spectators discover the wine, Scot informed his readers that “you may saie you have drunke verie much”). Similarly, performers wishing to stage the chest-stabbing illusion were advised to place a protective plate on their chest, followed by a bladder of blood, and then a flesh-colored pasteboard designed to resemble your actual chest. During the performance, the conjuror plunged a dagger through the pasteboard and bladder, but was protected from harm by the back plate. Performers were advised to make the pasteboard appear as realistic as possible (including the use of chest hair) and to use the blood of a calf or sheep (“but in no wise of an oxe or a cow, for that will be too thicke”). Scot warned readers that such feats may carry a genuine risk, describing how one performer became drunk, forgot to don the protective plate, stabbed himself in the stomach, crawled into a nearby churchyard, and died.

Scot’s radical approach to witchcraft proved highly influential and resulted in him making several powerful enemies. In 1597, King James VI of Scotland produced his own book in which he passionately argued in favor of witch trials. At the start of his book, James explains that one of his main motivations for putting pen to paper was to argue against the “the damnable opinions of… the one called SCOT an Englishman,” who James described as being “not ashamed in publike print to deny, that ther can be such a thing as Witch-craft.”

Scot died in 1599, but his ideas lived on. Over time, the belief in witchcraft began slowly declining throughout Europe and the barbaric witch hunts eventually came to an end. Many historians have argued that The Discoverie of Witchcraft played a key role in making this possible.

Scot’s book also had a tremendous impact on conjuring, with some of the material from The Discoverie of Witchcraft being reproduced in two later magic books: The Art of Juggling or Legerdemain (1612) and Hocus Pocus Junior: The Anatomie of Legerdemain (1634). The popularity of these works encouraged other authors to produce similar manuals and, over time, these manuscripts of magical secrets have come to form the bedrock of modern-day conjuring.

The Discoverie of Witchcraft is highly sought after by both book collectors and historians of magic, and I am proud to have a copy in my museum. It helped lay the foundations for magic and so provides the perfect starting point for our journey into the art of conjuring.

CHAPTER 2 The Pastry Chef

This curious collection of mysterious clocks, a beautiful model orange tree, and a strange dollhouse-sized French bakery sit at the heart of my museum. Together they represent perhaps the most important seven years in the history of magic.

Jean-Eugène Robert was born in the French city of Blois in 1805. At the time, Blois was a major European center for clock making, and home to hundreds of artisans and craftsmen. In his twenties, Robert began to train as a watchmaker and became fascinated by finely engineered mechanisms. Although historians have struggled to discover exactly how Robert became interested in magic, in his memoirs he claims that during his apprenticeship he ordered a book on watchmaking (Traité de l’Horlogerie) but was mistakenly given a work on rational recreation (Dictionnaire Encyclopédique des Amusements des Sciences Mathématiques et Physiques). This two-volume encyclopedia of fun and games apparently revealed the secret to many magical illusions, including how to read minds and appear to decapitate a pigeon. Mesmerized by this trove of knowledge, Robert entered the world of magic.

In 1830, Robert married Josèphe Cecile Houdin, adopted her surname, and became Robert-Houdin. Around the same time, he moved to Paris to pursue his joint love affair with mechanism and magic. With the cogs and gears of his mind in full spin, Robert-Houdin patented a small clock that automatically produced a lit taper when the alarm sounded, thus preventing people from stumbling around in the dark when they woke up. He also created several “mystery clocks” that consisted of clock hands mounted on a transparent glass dial, and the dial sitting on a clear crystal pillar. Despite the lack of any apparent visible mechanism connected to the dials or hands, the clocks kept perfect time.

At the time, the French aristocracy and bourgeoisie were keen to find new ways of flaunting their considerable wealth, and one approach involved buying intricate and expensive automata to entertain their friends and visitors. Eager to make the most of this highly lucrative market, Robert-Houdin designed and built several highly complex automata, including his pièce de résistance, T...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Secrets of the Conjurors Revealed

- Chapter 2: The Pastry Chef

- Chapter 3: Prestidigitation and the Presidency

- Chapter 4: Will, the Witch, and the Watchman

- Chapter 5: The Man Who Knows

- Chapter 6: “P” Is for Private

- Chapter 7: This Is My Wife

- Chapter 8: We’re Off to See the Wizard

- Chapter 9: The Queen of Magic

- Chapter 10: The Palace of Magic

- Chapter 11: Author Unknown

- Chapter 12: Notes on Steam Engines, Pumps, Boilers Hydraulic, and Other Machinery

- Chapter 13: Condemned to Death by the Boxers

- Chapter 14: Escaping Mortality

- Chapter 15: The Magician Who Made Himself Disappear

- Chapter 16: Lighter Than Air

- Chapter 17: Divided

- Chapter 18: Free Rabbits

- Chapter 19: The Suave Deceiver

- Chapter 20: The Human Index

- Chapter 21: If They Don’t Know You, They Can’t Book You

- Chapter 22: In Pursuit of Perfection

- Chapter 23: Blood on the Curtain

- Chapter 24: The Man Who Fooled Houdini

- Chapter 25: The Mystery Box

- Chapter 26: The Magic in Your Mind

- Chapter 27: The Magician Who Believed in Real Magic

- Chapter 28: On the Shoulders of Giants

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Sources and Further Reading

- Index

- Image Credits

- Copyright