![]()

1.

Introduction

Susan Sherratt

This book represents the proceedings of a conference organised by the Department of Archaeology at the University of Sheffield on 1st–4th April 2008 in memory of AndrewSherratt. The conference itself took place under the title “What Would a Bronze Age World System Look Like? World systems approaches to Europe and western Asia, 4th to 1st millennia BC”, which incorporated a blatant reference to the title of one of Andrew’s more widely known and in some ways more controversial publications (Sherratt 1993a). In this he argued that it was possible to combine the insights of detailed regional studies with a broader continental perspective to develop a more sophisticated approach to inter-regional relationships between temperate Europe and the Mediterranean in later prehistory – an approach whose aim was to uncover the large-scale systemics behind long-term change and situate these within a larger structural setting which had the ability to explain not only why and how developments took place but why they took place where and when they did. Adapting (but certainly not simply adopting) some of the more general concepts and terminology of Immanuel Wallerstein’s early modern ‘World-System’(Wallerstein 1974), he argued that, for much of its Bronze Age, temperate Europe acted as a ‘margin’ to an expanding Near Eastern/Mediterranean ‘core-periphery’ system with its ultimate origins in the 4th millennium urbanisation of southern Mesopotamia, and in this capacity was not only indirectly (and selectively) affected by innovations pulsing out from this system but, through the formation of successive long-distance axial routes directly related to the growth of the latter and the flows or trickles of materials, ideas and practices which moved in different directions along these, began to experience the kinds of structural changes which led to its progressive integration into the system as a whole during the course of the Iron Age.

In doing this, Andrew was fully aware that he was plunging into a number of areas of controversy: above all, into that between competing ‘evolutionary’/‘autonomist’ and ‘diffusionist’/‘interventionist’ paradigms for interpreting European prehistory, which represented the continuation of the old antagonisms between ‘processualist’ and ‘culture-historical’ readings of archaeology (it came as no surprise at all, therefore, to find himself accused of dressing up old-fashioned diffusionism in a more fashionable – but irrelevant – terminology [cf. Sherratt 1993b]); but also into that which lay between modern world-historians dealing consistently with a macro-picture and the generally more parochial concerns of archaeologists confined by trends within the history of their discipline to ever more detailed analysis of the contents of narrow regional or chronological boxes. As a result, the notion of a ‘Bronze-Age world-system’ has tended to be attacked on two fronts. On the one hand, it has been misunderstood (sometimes wilfully) as an attempt literally to transplant Wallerstein’s analysis and terminology into the conditions of prehistory – which, given that there is much in his early modern World-System which explicitly precludes this, is, in any case, a logical impossibility; while, at the same time, the idea of political subjugation, along with the essentially politically-derived (and ideologically distasteful) notion of ‘dependency’, has often been accorded an artificial prominence within this misunderstanding. On the other hand (particularly from the perspective of the equally politically-derived body of ‘post-colonial’ theory), a world-systems approach has been accused of sweeping in blanket-fashion over local variations in social or cultural structures and trajectories, and of focusing on the interactions of regions at the expense of individuals – even though such an approach of itself need present no obstacle to the detailed examination of local socio-cultural practices and peculiarities or of the roles of individuals (where visible). Rather, the wholly contextual nature of such an approach logically demands that questions of interaction (and of the motivations, mechanisms, structures and effects – or lack of effects – of interaction) be investigated and, if possible, explained at every conceivable scale and level.

Contrived though some of the disputes might appear to be, there is nevertheless a serious and sustained debate to be had about the usefulness of what might loosely be called a ‘world-systems’ approach in explaining structural change over the long term in various areas of Europe and western Asia. And it was with this in mind that we decided that the aim of the conference should be to review its applicability to interpreting aspects of the long-term archaeological record within this macro-region and to discuss the ways in which (if at all) such an approach or perspective might best be tailored to prehistoric or early historical contexts. Hence the title under which the conference was planned and held.

If we might have been a little anxious at the outset to avoid the conference turning into a series of tedious arguments between proponents and opponents of ‘world-systems’ approaches, then we need not have worried. On the contrary, once it was underway we realised that our initial ambitions had been far too limited, and that the title did not adequately reflect either the scope of papers and posters presented at it and the thrust of the very lively and wide-ranging discussions which took place during its course, or, indeed, what many of the participants were really talking about. Andrew himself had been gradually moving away from a Wallersteinian vocabulary, in order to make clear to those who could not or would not see it that a ‘world-systems’ approach to the prehistoric or ancient world did not – and could not – involve a retrojection in any recognisable form of Wallerstein’s World-System. The concept of ‘margin’ had already been introduced (Sherratt 1993a); the term ‘structural interactionist’ became interchangeable with ‘world-systems’ (e.g. Sherratt 1995) and latterly seemed set to replace it altogether (Sherratt 2001); and he was experimenting with a variety of metaphors through which to conceptualise the spatial, chronological and structural nature of change produced by the interactions of a growing system (Sherratt 2000; 2005). Though the papers in these proceedings range in scope from the near-global over several millennia to the regional or even site-centred over a much more limited timespan, from the synoptic to more detailed thematic focuses and from the highly abstracted to the tangibly concrete, they all deal with interactions which reveal themselves to be systemic in character and to have systemic effects, and to that extent fall within what Andrew meant by a ‘world-systems’ perspective while obviating the rhetorical antagonisms which that rubric so often evokes. They present a series of analytical glimpses, at a wide variety of scales of chronological and geographical resolution, of an economically and culturally increasingly interwoven world, the fabric of which – far from being plain and uniform – is made interesting by a multitude of diverse and complex patterns when one looks closely. If at least two of the papers emphasise the importance of non-metaphorical textiles in the interweaving of this world, the metaphor itself seems temptingly apt in its own right, since little can be more systemic and structured than the interactive relationships of the warp and the weft, which are nevertheless open to a great variety of twists and turns, or to the picking up of new threads and the dropping of others, within the overall context of the developing cloth.

The conference brought together an unusually diverse group of people with a remarkable range of geographical, chronological and topical interests and perspectives – people who perhaps would not normally find themselves together at a single meeting and who, thankfully, as a body would probably never be capable of reaching the consensus of ‘received wisdom’. They included old friends of Andrew’s (and in some cases old sparring-partners) of many years standing, as well as people he had never met but would have relished encountering. After the good-humoured discussions which formed such a stimulating part of each of the three days, a number of us came away thinking how much Andrew, whose interests knew few limits and who delighted in debate, would have enjoyed it. As John Barrett said in his closing remarks, you could almost hear him purring.

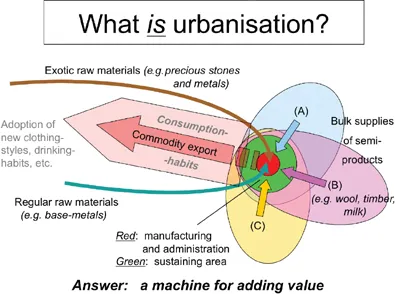

It seems only right to allow Andrew the last (if more or less literally first) word in the book of the conference held in his memory with a piece he started writing (but never quite finished) for a projected ‘White Pages’ section of his ArchAtlas website, which he envisaged as hosting text-based discussions on aspects of the general themes of the website. It includes several of the observations, ideas and concepts (and one of his trademark diagrams) which informed both his view of the inevitable logic of a long-term structural approach to the history of human societies from an archaeological perspective and the philosophy behind ArchAtlas. It also touches on some of the more general issues raised or discussed by the papers in this book.

Before leaving the reader with Andrew’s own words in the following chapter, however, some acknowledgements are due. John Barrett (then Head of the Department of Archaeology at Sheffield) came up with the initial idea for the conference and set the arrangements in motion. John Bennet (his successor as Head of Department) saw it through and contributed greatly both to its successful organisation and to the editing of this volume. Deborah Harlan, Valasia Isaakidou and Vaso Tzevelikidi provided a magnificent reception on the first evening and, helped by Tim Cockrell, Angeliki Karathanou, Angeliki Karagianni, Kate Lantzas, Anastasia Vasileiadou and Corien Wiersma, ensured the smooth running of the conference in numerous ways; and Jo Mirfield kept track of participant registration and more generally the financial side. Above all, Toby Wilkinson took on the lion’s share of responsibility for its detailed practical organisation (including the website) and for making sure that this book reached completion. The Economic History Society, the Past & Present Society, the Council for British Research in the Levant, the Devolved Fund of the Arts and Humanities Division and the Humanities Research Institute of the University of Sheffield generously provided funding or free use of facilities, and to all of these we are extremely grateful.

References

Sherratt, A. (1993a) What would a Bronze-Age world system look like? Relations between temperate Europe and the Mediterranean in later prehistory. Journal of European Archaeology 1(2), 1–37.

Sherratt, A. (1993b) ‘Who are you calling peripheral?’ Dependence and independence in European prehistory. In C. Scarre and F. Healy (eds.) Trade and exchange in prehistoric Europe,245–255. Oxford, Oxbow.

Sherratt, A. (1995) Reviving the grand narrative: archaeology and long-term change. Journal of European Archaeology 3(1), 1–32.

Sherratt, A. (2000) Envisioning global change: a long-term perspective. In R. A. Denemark, J. Friedman, B. K. Gills and G. Modelski (eds.) World System History: the social science of long-term change, 115–132. London and New York, Routledge.

Sherratt, A. (2001) World history: an archaeological perspectivne. In S. Sogner (ed.) Making Sense of Global History. The 19th International Congress of the Historical Sciences Oslo 2000 Commemorative Volume, 34–54. Oslo, Universitetsforlaget.

Sherratt, A. (2005) Contagious Processes. ArchAtlas, February 2010, Edition 4, http://www.archatlas.org/Processes/ContagiousProcesses.php. Accessed 15th March 2010.

Wallerstein, I. (1974) The Modern World-System. New York, Academic Press.

![]()

2.

Global Development

†Andrew Sherratt

In discussing the likely developments of the next few decades, economic commentators take it as a commonplace that the centre of gravity of the world is moving towards the Pacific. Western Europe and eastern America are losing their centrality, as activity shifts to Asia and the west coast of the Americas. A similar shift took place in the 16th century, when power and influence moved from the Mediterranean, especially Italy, to the Atlantic seaboard and especially the countries bordering the North Sea. Indeed, the pattern seems to be a persistent one, for Mediterranean centrality itself took over from a more ancient, Near Eastern one, even though Persia remained another potential centre of power, until the same shift from trans-continental to oceanic routes which brought the Atlantic to prominence overshadowed all of the inland parts of the former Silk Road. There is a situational logic to successively dominant areas in the world economy.

These patterns are so evident that it is surprising that the obvious conclusions have not been drawn: that prosperity is an outcome of geography, and that at any one period it is a particular location within a pattern of connections which gives the advantage. Theorists who have placed the emphasis on forms of government, law, culture, religion or whatever have neglected the much more important, underlying structural determinants of economic prosperity. (What is more, even political characteristics are not unrelated to geography: the liberal democracies with figurehead monarchies around the maritime world of the North Sea; the totalitarian tendencies of more landlocked territories, for instance.) Certainly, these other factors may exercise an influence, on a timescale of decades or between adjacent countries, but as explanations of the long-term patterns of development they simply ignore much more basic considerations. It can only be because of the marginalisation of geography, and its separation from history and economics, that such fundamental facts have been ignored. Historians, too, must bear some responsibility – partly for largely avoiding any discussion of theory (taking it ready-made from more explicitly comparative disciplines), partly for history itself being so specialised both in time and space as to obscure structures on a scale larger than that of a few centuries or across the boundaries of national entities. In consequence of this over-specialisation and myopia, even the most obvious facts have been ignored, gravely impeding our understanding of our present condition as much as of our past history.

It is the privilege of archaeology to deal with all scales of phenomena, from the global to the local, over timescales from the momentary to the long term. There is no inherent reason why historians should not think with such flexibility, any more than that they could make major contributions to social theory or consider variables in space as well as time; it just happens that archaeologists (who in absolute numbers are a trivial fraction of the numbers of historians) have done it first. The sooner archaeologists lose this virtual monopoly, the better; but until that happens, they have a special responsibility to demonstrate these observations and to disseminate such insights. This, then, is the motivation to present a long-term, structural history of human societies, from an archaeological perspective.

Terms such as ‘prosperity’ imply their opposite, which is not necessarily impoverishment and dependency – until relatively recently – but does involve a degree of loss, if only of working harder for someone else’s benefit. (Right-wing historians of working-class origin, who celebrate how much better life has become during their own lifetimes, neglect the fact that this deprivation has simply been exported to Mexico or Bangladesh.) Such phenomena of unequal development have characterised only the last six thousand years of human existence, since the beginnings of urbanism. Hunting populations in various parts of the world, in the ice age and afterwards, enjoyed radically different climatic conditions, and different amounts of natural resources; but they did not do so at each other’s expense – and nor did the first farmers, expanding to take over land from the hunters and foragers, and themselves experiencing nature’s own inequalities and capriciousness in relation to their crops and livestock. It was with the complex, regionally specialised economies which grew up with, and were integrally related to, the development of complex societies in urban settings, in which institutionalised spatial inequalities, independent to some extent of natural variability, first arose. Structural history, in the sense of the growth of interdependent populations in complex but clearly contrasting relationships, is characteristic only of this time, and (again not fortuitously) coincides with the development of written scripts – though not all of the populations involved, and only certain segments of the ‘literate’ ones, could actually write, and in any case the vast majority of written records have perished. Much of the primary evidence, therefore, is archaeological, and it is perhaps not surprising that archaeologists have taken the initiative in seeing such phenomena as a whole.

The term structure is appropriate in describing the development of the world in the last six thousand years because of the growing articulation between the activities of populations in one area and those in another; and not merely because of a greater propensity for the exchange of goods, but a change in the nature of the goods exchanged. It was not simply based upon the exchange of one naturally occurring material for another, or even of one cultivated commodity for another, but rather centred on the circulation of manufactured goods, and thus inevitably on materials necessary to produce them (and the victuals needed to sustain their manufacturers and distributors). In a more abstract description, it included added value as well as primary value, and therefore involved culture and belief as much as mere materiality. Manufactured materials – organic and inorganic – embodied ideas and aspirations, even emergent identities, which provided both motivation and means for the satisfaction of demand. That is to say, demand itself was stimulated – at least for the few – by a constant “provocation of gluttonie” (in Sir Thomas Heriot’s words), in new consumables both in the literal sense and in the sense of more durable goods consumed in use and display. It is hard to separate the directions of the causal arrows linking social display, social differentiation, economic and social specialisation, the movement of goods, the development of facilities for production and distribution, the elaboration of portable material culture and also of domestic, institutional and community buildings which provided the settings for its consumption. All were elaborated in concert, in certain conditions and in certain very specific societies.

Like the evolution of multicellular organisms, it seems likely that the development of larger structures was predicated upon the emergence of new forms of organisation at the level of replicable entities; and that these made possible the building up of more complex and differentiated relationships between otherwise organisationally similar units and groups of such units. Cities (or towns: the distinction is not absolute or simple) and their h...