![]()

I - From My life

When I Was Not Yet A National Socialist

In the twenties I was an employee of the Austrian branch of the Vacuum-Oil Company, I received a salary that was large for the conditions of that time and lived happily and carefree. In 1930 I was introduced by a former senior lieutenant of the Imperial and Royal Army, who was at the same time an official at the oil company, to the “Schlaraffia” in Linz which had in the club-house an extremely nice cellar room. I became acquainted there with all sorts of people, for example, doctors from the General Hospital in Linz, actors, big businessmen, all from Linz.

As part of the welcome ceremony I was instructed to bow before a stuffed eagle owl which sat in a corner halfway up the club-house room, and then I was greeted by all those present. The arch chancellor then gave a sign, whereupon music was struck up on a spinet-like instrument and all put on their dunce-caps hung with all sorts of coloured trinkets. Near one of the members stood a swastika; to my question why, he said “But naturally – we do not accept any Jews!” That made a great impression on me. I was expected to give an entry speech as best as I could, humorous but intellectually substantial; I had therefore already decided what subject I would choose. Finally, as the evening progressed, we went to the Café Central, and because I was, as a young man of 23, in a good mood I ordered a round of a fine variety of wine for the table. At the same table sat the dialect poet Franz Resel. After some moments he left the café somewhat enraged with a remark to the effect that I did not need to come back henceforth. Why? Simply because I had mentioned that I was a member of the German-Austrian Frontline Soldiers’ Association, which was composed of two different groups, one monarchist in attitude and the other nationalist, which was especially anti-Marxist.

Franz Josef-Platz in the Austrian city of Linz, 1931At that time, the Republikaner Schutzbund1 ruled the streets and, along with it, on the basis of a privilege of the German-Austrian government, the Frontline Soldiers’ Association under the leadership of Colonel Hiltl.2 Because I came from the association of the monarchist party, I was immediately accepted in the “German Austrian Young Frontline Soldiers’ Association”. In the Monarchist Club we had among our peers officials as well as sons and daughters of officers. In the Frontline Soldiers’ Association there were officers with many high decorations, Austrian corps men, commanders, sergeants, ordinary guards; they were all united under the banner of anti-Marxism. In the Upper Austria section, the Major General von Ehrenwald well-known from the first World War had a certain place of honour; his wife was dead; one of his former commanders from a traditional regiment was his servant, who while wearing white cotton gloves had the task of shuffling the glasses to and from his master and the few guests.

On many a Sunday afternoon we travelled by tram to the Ebelsberg near Linz where there was a large shooting range. The Frontline Soldiers’ Association had been granted permission to even shoot with military weapons. The Major General, pressed into my hand for the first time in my life a military carbine and exhorted me to fire the weapon. The Major General always carried – even in radiant sunshine – an umbrella and narrated to everybody that he met, some small episode from a battle, where it was not at all important if one understood any of it or even paid any attention to it. The Major General brandished his umbrella around in the air, rolled his eyes, twirled his moustache and gesticulated; and once he tried to describe a situation especially vividly with a torrent of words so that everybody understood: now the General is standing in the midst of battle! That naturally impressed us boys very strongly; and we often sought the company of this worthy old gentleman.

The Monarchist Club provided the opportunity for convivial meetings where we could meet one another, have a small drink and chat a little about Bismarck. In the German-Austrian Frontline Soldiers’ Association there prevailed a rather more militant atmosphere. I had in any case, alongside my pleasant and well-paying job, political views which may be characterised as “nationalist”; for the principle of the Frontline Soldiers’ Association was the general welfare of the nation. I was anti-Marxist because, well, one was in our circles, but I did not understand politics in any real depth. Occasionally our Major General clarified things for us.

At this time I had become engaged to the daughter of a senior officer of the constabulary. When we had nothing better to do in her father’s parlour we frequently sprawled on the windowsill and looked out on the street. A hundred metres from the barracks there was an inn, the “Märzen Cellar”, where at certain seasons there was a good bock beer; in this inn members of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party would frequently hold meetings. In our circles we used to say that the NDSAP consisted only of idiots and the frustrated. This local branch was led by a man called Andreas Boleck,3 who was the “Gauleiter”,4 as one called it, of Upper Austria. After the first World War, Bolek came to Linz as a former lieutenant of the Imperial and Royal Army and had married the daughter of a local butcher. Later he got a position in the Linz Tramway and Electricity Company, where my father was a director.

At that time the NSDAP meant nothing in Upper Austria. When I and my fiancée looking out through the window, saw troops of twenty to twenty five men – partly in brown shirts, partly with swastika bands and partly without any insignia at all – marching past singing, I felt as if something rushed into my blood from these songs. They marched “differently” from the Republikanischer Schutzbund, they sang “differently” and, when my fiancé once said to me: “These idiots!”, I answered her: “But they have order and discipline – and they march well!” My fiancée soon left me, especially when I told her that I admired these men, for they had fought for their fatherland, and were idealists.

At that time I used to go every forenoon to a certain coffee-house to drink my black coffee, and read the Linzer Tagespost and the Volksstimme, and to wait until the only copy of Völkischer Beobachter5 that was available in the pub became free, which the waiter Franz always brought me for a small tip. There I read how at that time SA and SS men were killed and borne to the grave in a demonstration of their faith: “They died for something great!”6 I read also how even the funeral processions were attacked by their opponents in the local community. All that infuriated me immeasurably and caused to develop in me an inclination and even friendship towards those “idiots” who marched singing freedom songs through the streets past the police barracks.

I Became A National Socialist

One evening I received an invitation from Gauleiter Bolek to a meeting of the NSDAP in the “Märzen Cellar”. I went there. After Bolek had spoken I came upon Ernst Kaltenbrunner;7 who was wearing the SS uniform which I saw here for the first time. Then he said to me the words that I still remember: “You … you belong to us!” Then he drew out a sheet of paper, filled it in, and I only needed to sign it. I still remember that I did not ask any further questions, but was happy and proud to belong now, like Kaltenbrunner, to the SS. That was in 1931.

Kaltenbrunner’s father and my father were business friends in Linz so we knew each other quite well. Kaltenbrunner himself was at that time active in a legal position in his father’s office. So I became an SS man.

Kaltenbrunner and I then spoke about the Jews and Freemasons; and he said in this connection: “The Schlaraffen8 organisation was a preliminary stage to Freemasonry; these are enemies of the Reich”. I expressed my own opinion, but Kaltenbrunner did not agree with me, and he became quite adamant so that I felt as if I was half a criminal because I had myself been part of these Schlaraffen. When I then told him that I had anyway been expelled, he laughed; then we drank a beer together.

As an SS man I had now to hold watch every Friday evening in the “Brown House” in Linz. Since many of my SS comrades were unemployed, I ordered in the Café Bahnhof sandwiches and beer for everybody. During this time we had to participate in some debates, also once in the Volksgarten Hall, where Bolek was supposed to speak and the Communists had already in the afternoon filled the hall with up to 2,000 men in order to make the meeting impossible for us. Although we had rented the hall, the police gave only Bolek and 25 SS men permission to enter. So we went in; the speech by Gauleiter Bolek was short, he could only say: “My German national comrades ...” and already an enormous racket broke out, I heard Kaltenbrunner calling “Get the guys”, for the Communists placed their women right in front of the podium, and behind them collected the men, mostly bellowing, drunken shipyard workers. We all stood on the podium and had to protect our Gauleiter from the charging people with our boots and shoulder straps strengthened with leaden knots. After we had done this successfully we withdrew, but with losses. So, for example, the kidneys of the later adjutant of the SS Reichsführer,9 staff sergeant Breuer, were battered; the voluntary fire brigade took him to the hospital. The “Volksgarten” Hall was smashed up – to the last glass and the last mirror.

One day a delegate of the engineering team, apparently a technical sergeant, came to me and in a serious tone gave me the leadership of the Motor Squadron unit of the 37th SS Standard. I was thus “Motorsturmführer”,10 but I had no idea what was required of me. So I asked for a job description in order to become acquainted with the command. There was another man who wished to become an adjutant of mine, but I thought that I must first organise motor vehicles, which could also cost me some money. I still continued my service at the oil company, and at work I wore my insignia of the NSDAP.

I became a missionary for the NSDAP, and preached everywhere, even to my customers. As a result of this the oil company transferred me to Salzburg. I had obtained my post at the company partly through the help of a Jew and was able to get along with any Jews whom I met. In Salzburg a Jew became a technical inspector at the oil company, but in spite of advice against doing so, I wore my SS insignia even during business meetings; I was after all single and I had no responsibilities of any sort. On Whitsun 1933 I was dismissed.

The German consul prepared for me a letter with the content that I was dismissed “from the Vacuum Oil Company on account of my membership in the SS”. Kaltenbrunner sent me to Germany with the commission of reporting to the “boss” in Passau, the Gauleiter Bolek, who had in the meanwhile moved there. I packed my brown shirt, riding breeches and boots into my bag.

With the Austrian Legion

Bolek lived in the Bahnhof street in Passau as the Gauleiter of Upper Austria. There it was suggested to me that a military education would not hurt; I was to go to Dachau, but the motor team leader, who had named me Motorsturmführer at one time, took command of me in Passau: that was Major von Pichl. I was then promoted to SS Sergeant and received my first medal. It was my task to watch over, with my eight men, a certain section of the German-Austrian border in accord with the chief of the border police station of Passau. I had to lead National Socialists who for some reason had to flee from Austria over the “green line”, even smuggle our propaganda material in the same way into Austria; the NSDAP had been for a long time prohibited in Austria. I got a motorcycle and did service in the Bayerische Wald.

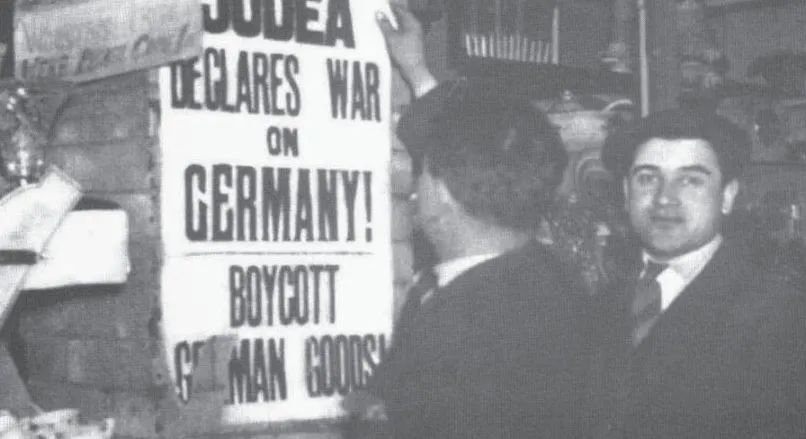

1933, it took the Jewish lobby six years to achieve their war against Germany.Christmas 1933 we celebrated in Passau. The city councillors came to us, eight people who had left Austria and we were on this evening absolutely regaled in the then flourishing Passau. We had placed our heavy machine-gun at a stream, near which in our quarters stood the Christmas tree.

In the first months of 1934 I received an order to report to the battalion of the “Austrian Legion” SS-I in Dachau. I arrived at the barracks as a civilian there with a bag, borne by a porter, and an umbrella … I never saw the bag or umbrella again. First I received many things – like blue-white chequered bed linen – some sneakers were also thrown at my head which I was however able to catch in time. But it was still better than in the Lechfeld Cloister, where I waited for two months before I succeeded in obtaining so much as an SS tie rod. There we were in a really old first World War army camp and we even had to pick out the pieces of meat and potatoes with our fingers because there were neither knives nor forks nor spoons. We slept on straw. I moistened my handkerchief and placed it as a filter on my nose against the dust. But one got accustomed even to that.

In Dachau on the other hand everything was very orderly. I passed my shooting exercises and belonged to SS unit Sturm 1311. We were subdivided into infantry and combat patrol: to the infantry belonged the narrow-chested tall ones, to the combat patrol the “athletically” built; I went to the combat patrol. The Sturmführer was a former staff sergeant of the Bavarian Provincial Police, a feared “slave-driver” whom we hated like sin. In spite of my preparedness for self-denial – I could after all have led a better life at home – and in spite of my natural joy in everything, my life was now nourished only on murderous thoughts. When in the mornings the bugle sounded, fury rose high in me. I got used to waking up a quarter of an hour earlier in order to be able to dress in ease before the awful bugle signal sounded. We then did twenty minutes of early morning exercises on the double; from there we went to a water tap. Hardly did we reach this water tap to dash a few drops of water onto our faces than we would already be shouted to the coffee table; hardly had we stuck the bread in our mouths and gulped the cold coffee sludge, when we had to fall in line and report for roll-call. The Sturmführer greeted us in a friendly manner with “Good morning people”, then the badgering began once again. I escaped only into “murderous thoughts” against this former police chief.

The training-camp parade ground was on the “Schinder meadow”, where prickly grass and gravel tore our boots. Half the company reported to the parade ground. I had myself bound with gauze and plaster – but in the first minutes of crawling on hands and knees everything came off and was bloody again. Years later I mentioned that staff-sear...