![]()

1

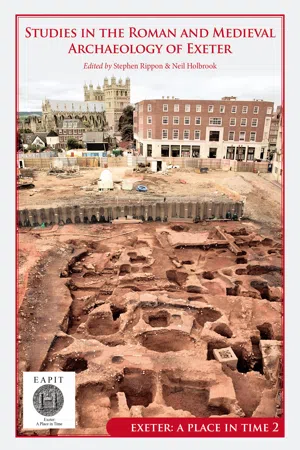

Introduction: Studies in the Roman and Medieval Archaeology of Exeter

Stephen Rippon and Neil Holbrook

This is the second volume derived from the Exeter: A Place in Time project (EAPIT), an introduction to which can be found in EAPIT Volume 1 – Roman and Medieval Exeter and their Hinterlands. Whereas EAPIT 1 presented a discussion of the development of Exeter and its hinterland from the Roman through to the medieval period, this volume contains a series of more detailed contributions that provide some of the underpinning data used in Volume 1. This includes stratigraphic reports on four of the most important previously unpublished excavations – at Trichay Street, Goldsmith Street Site III, 196–7 High Street and Rack Street – that between them revealed for the first time parts of the Roman legionary fortress that underlies Exeter, as well as long sequences of occupation that tell the story of how Exeter subsequently developed as a Roman civitas capital, Late Saxon burh, and later medieval city. These descriptions of the stratigraphic sequence are not accompanied by the traditional specialist reports as the relevant assemblages were published in a series of three ‘Exeter Archaeological Reports’ (EAR) covering The Animal Bones From Exeter 1971–1975 (EAR 2: Maltby 1979), the Medieval and Post-Medieval Finds from Exeter 1971–1980 (EAR 3: Allan 1984a), and the Roman Finds from Exeter (EAR 4: Holbrook and Bidwell 1991). Microfiche in Holbrook and Bidwell (1991) and Allan (1984a) also contain lists of the dating evidence from Trichay Street, Goldsmith Street Site III, 196–7 High Street, and Rack Street as well as other sites excavated between 1971 and 1979 (the inventory of pottery from Roman sites excavated between 1980 and 1990 is now available on the EAPIT webpage (http://humanities.exeter.ac.uk/archaeology/research/projects/place_in_time/resources/inventory/).

In addition to the pottery, Exeter Archaeological Reports 3 and 4 included specialist reports on nearly the full range of artefacts types, although some were relatively brief (e.g.the Roman ceramic building material) or not covered (e.g.Roman querns). EAPIT therefore provided the opportunity to fill in some of the gaps such as Malene Lauritsen’s analysis of the faunal assemblages that had not previously been examined (Chapter 9), Ruth Shaffrey’s study of the Roman querns and millstones (Chapter 14), and Mandy Kingdom’s analysis of the human remains from a series of medieval cemeteries (Chapter 19). We were also able to apply modern scientific and other analytical techniques to the finds now stored at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum (RAMM) which included David Dungworth and Carlotta Gardner’s re-analysis of the archaeometallurgical debris (Chapter 10), Cathy Tyers’ reassessment of the dendrochronlogical evidence (Chapter 11), and Sara Machin and Peter Warry’s analyses of the Roman ceramic building material (Chapter 13). Robert Kenyon has reassessed the significance of Claudian bronze coins from Exeter (Chapter 15), while Andrew Brown and Sam Moorhead have reassessed the Roman coinage from Exeter in the light of data collected by the Portable Antiquities Scheme (https://finds.org.uk/) for South-West England as a whole (Chapter 16).

A particular focus of EAPIT was Exeter’s ceramic assemblages and the evidence that they provide for its economy. Chapters 12, 17 and 18 therefore report on a series of scientific analyses that have established for the first time the sources of the clays used to make some of the important ceramic wares found in Exeter, and review how our understanding of its Roman and medieval trade has changed in recent decades. A theme that is common to most of these chapters is that rather than being simply specialist reports on the finds from an excavation, they have tried to explore what those artefact types tell us about landscape and society in Roman and medieval Exeter and its wider hinterland.

The structure of this volume is as follows. Chapter 2 provides short summaries of all of the significant excavations within Exeter and its immediate hinterland, expanding and updating the online site list produced by the Exeter Archaeology Archive Project (https://doi.org/10.5284/1035173). Chapter 3 presents three more detailed sets of data: a detailed discussion of the Roman legionary fortress plan by Paul Bidwell, and gazetteers of the evidence for Roman military and civilian streets and buildings. In Chapter 4 John Allan provides a study of the documentary evidence for St Pancras parish that was the location for three of the major excavations that EAPIT has written up (see below). Exeter has exceptionally rich medieval archives, and although in the past it has been doubted whether it is possible to locate the documented tenements precisely on the ground, this is what Allan has now been able to achieve for an important block of central Exeter where some of its wealthiest citizens lived. Chapters 5 to 7 then present the results of the three excavations in this central part of Exeter, at Trichay Street, Goldsmith Street Site III and 196–7 High Street. These three sites revealed some of the most complete sequences in Exeter, including buildings within the Roman legionary fortress, the civilian town, and the Late Saxon and later medieval city. In Chapter 8, the results from a fourth excavation – Rack Street – are then presented that included sections across the defences of the fortress and Early Roman town.

There follows a set of papers that describe the results of multi-period analyses of three categories of material. In Chapter 9 Malene Lauritsen summarises the results of her PhD that studied a series of important Roman and medieval animal bone assemblages that had not previously been examined and which provide some of the data used by Mark Maltby in his overviews of Exeter’s faunal material in EAPIT 1 Chapters 5–8). Of particular significance is the recognition of significant variations in meat consumption across different parts of Exeter in the medieval period, and the importance of marrow fat in past diets during all periods. Chapter 10, by David Dungworth and Carlotta Gardner, uses modern scientific techniques to study the archaeometallurgical debris from Roman and medieval Exeter which testifies to the significance of the South-West’s mineral resources. Back in the 1970s Exeter saw some of the earliest applications of tree-ring dating in the South-West, and in Chapter 11 Cathy Tyers reviews this dendrochronological evidence from archaeological structures within Exeter, and explores what it tells us about the supply of timber (that was primarily from local sources).

The next group of chapters explore Roman material culture in Exeter and its hinterland. In Chapter 12 Paul Bidwell provides an overview of the pottery supply to Roman Exeter in its military and civilian phases. The chapter includes reports on various strands of EAPIT’s scientific analysis of key fabrics found in Exeter whose source was not previously known, identifying clay sources immediately east of Exeter in the Ludwell Valley (South-Western Grey Ware storage jars), on the western side of the Blackdown Hills (South-Western Black-Burnished Ware 1), and in the Teign Valley in South Devon (the so-called ‘Fortress Wares’). Chapter 13 reports on the analysis of Roman ceramic tile from Exeter and across Devon by Sara Machin and Peter Warry, showing how production close to Exeter was gradually replaced by a series of kilns across its wider hinterland. In Chapter 14 Ruth Shaffrey presents a review of the evidence for quernstone manufacture and distribution, showing how – with the exception of the Roman military period, when querns were imported from mainland Europe – only local sources of stone appear to have been exploited by Dumnonian communities. Two papers then explore the Roman coins from Exeter and the South-West more generally. In Chapter 15 Robert Kenyon shows how the analysis of Claudian bronze copies supports the suggested foundation date for the legionary fortress at Exeter of c. AD 55, while in Chapter 16 Andrew Brown and Sam Moorhead then take the story forward by comparing the patterns of coin loss in Exeter with its South-Western hinterland and selected other Romano-British cites. This shows that while Exeter saw similar patterns of coin loss compared to other towns, the South-West Peninsula was not as heavily monetised as other parts of lowland Roman Britain.

The final three papers explore aspects of Exeter’s medieval archaeology. Chapters 17 and 18 report on EAPIT’s programme of scientific analyses of various ceramic fabrics found in Exeter and whose provenance was not previously known. Chapter 17 focusses on Exeter’s pottery supply from local and north European sources, while Chapter 18 covers southern Europe. Finally, Chapter 19 presents a summary of Mandy Kingdom’s thesis on 463 human burials from four excavated medieval cemeteries: the Late Saxon minster and Cathedral Close, the Dominican friary (Black Friars), Franciscan friary (Grey Friars), and the extra-mural St Katherine’s Priory in Polsloe. This reveals that the majority of Exeter’s medieval population had adequate to good nutrition, health and longevity, and that life expectancy improved over time.

Throughout this volume excavations in and around Exeter are referred to by their EAPIT Site Number as listed in Chapter 2 (that also includes location maps).

The Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery, Exeter City Council, holds the copyright for all images given as ©RAMM.

Note on nomenclature: Exeter’s gates and quarters

The axes of Exeter – based upon the major roads that run between its four gates – run NE to SW and NW to SE (Fig. 1.1). An historical anomaly is, however, that the medieval gates were – and still are – called North, East, South and West (and so – for example – the gate on the SE side of the city was and is called the South Gate as opposed to the South-East Gate, e.g. Hooker’s Chronicle for the years 1308 and 1328, and Hooker’s Antique Description, 52, 55, 59). To complicate matters further, when the Roman legionary fortress was discovered its gates were named according to their correct orientation which means that the North-West Gate of the Roman fortress and early town is just 40 m from what in the medieval period was called the North Gate. As all the existing literature on Exeter uses this different terminology it is retained here. Figure 1...