![]()

Part I

THE BODY

![]()

Chapter 1

JENIN: LIVING WITH MARTYRDOM IN MOHAMMAD BAKRI’S JENIN JENIN AND SINCE YOU LEFT, AND JULIANO MER-KHAMIS’S ARNA’S CHILDREN

“This is a film about people in the Jenin camp, whose experience was very very hard”: this is how Mohammad Bakri described his film Jenin Jenin.1 Screened in Israel in October 2002 for the first time, then banned, and enduring several trials and much public bullying, Jenin Jenin has been widely covered by Israeli mainstream media for more than a decade to come: indeed, its display of the Jenin refugee camp struck an unnerving chord in the Israeli psyche.2 Filmed in five days in Jenin in April 2002, Jenin Jenin travels around the camp ruins right after the IDF destroyed large parts of it to the core, in what Israel called “Operation Defensive Shield,” and Palestinians, “The Battle of Jenin.” Bakri collected heartbreaking testimonies from the residents of the camp about their experience of the assault, as many of them had just lost their beloveds and homes. The screening of Jenin Jenin in Israel pushed against the normalized absence of their faces and voices from Israeli media.

In turn, Jenin Jenin ignited a wave of responses, engendering more documentary filmmaking about Jenin.3 Gil Mezuman’s Jenin: Reserves Diary (2003) and Pierre Rechov’s The Road to Jenin (2003) dismiss Bakri’s film, propagating the legitimacy of the IDF’s operation in Jenin. Invasion (2003) by Nizar Hassan, a Palestinian citizen of Israel like Bakri, explored the battle of Jenin from the viewpoint of an IDF Bulldozer driver and of the residents of the Jenin refugee camp who fought against the IDF’s invasion. In 2004, Juliano Mer-Khamis’s Arna’s Children joined the conversation, with a personal film about his mother, Arna Mer, and the children that both of them mentored in theater in the Jenin refugee camp in the 1990s. Alongside the footage from the theater classroom and stage, Arna’s Children features Mer-Khamis’s visit to the camp in 2002, after most of the children are no longer alive.4 In 2005, Bakri released Since You Left, which, among other endeavors, elaborated on the making of Jenin Jenin and confronted the fervent criticism that it drew. Like Jenin Jenin, Since You Left and Arna’s Children focused on the people experiencing the harsh consequences of the military violence against Jenin—yet in the latter two, the filmmakers included themselves in their films.

This chapter reads key scenes from the closely linked Jenin Jenin, Since You Left, and Arna’s Children. To start off the discussion, I attend to a couple of scenes from Bakri’s Since You Left, tracing living circumstances of ’48 Palestinians during and immediately after October 2000—circumstances that influenced Bakri’s decision to make Jenin Jenin. Since You Left illuminates that even when focusing only on their communities in the West Bank, documentaries by ’48 Palestinians are also very much about them. Rather than merely communicating the stories of Jenin of the 1990s and the 2000s, Since You Left, Arna’s Children, and Jenin Jenin unpack the complexities of living on in the refugee camp in Jenin since its foundation in 1953 to settle the survivors of the Nakba of 1948, and throughout years of Israeli military occupation since the 1967 war.5 Carefully attending to the documentary performances of witnesses of violence and death, the chapter works through the terms testimony, reenactment, and witnessing used afterward, while grappling with documentary approaches to representing “reality”: the chapter complicates theorizations of witnessing and testimony formative to trauma studies by indulging the power embedded in the documentary performance. The chapter unpacks the concept of “martyrdom” as it relates not to armed but to audiovisual, mediated, and mediatized Palestinian resistance. “Martyrdom” is a term fraught with meaning: in inciteful Islamophobic discourses in Israel and the United States, it has often been used interchangeably with “terrorism.” Yet an important meaning refers to the Arabic translation of “martyrdom,” or “shuhada,” as “witnessing.” The witnesses of violence and death in the Jenin refugee camp may thus be viewed as “living martyrs”:6 survivors of witnessed destruction who embody and carry the painful experience in and as their very own physical and affective state.

When performing their testimonies of what they have seen as reenactments, the witnesses filmed for Jenin Jenin do not guarantee to posit “what had exactly happened” with any measure of empirical accuracy. Rather, Jenin Jenin’s documentarian approach underlines whose pain gets to be filmed and shared depending on the circumstances of power informing the distribution of representation. As has been established, the trauma of witnessing destruction directly harms the usage of language about it. Yet on top of running the risk of unifying and depoliticizing the diversely positioned human experience, the Freudian genealogy of trauma carries harmful legacies of disbelief to survivors.7 In this chapter, I harness a politicized view of both the testimony of trauma and of documentary distribution in Israel-Palestine to show that the precise ways in which their testimonies have been performed and cinematized, including the testifiers’ bodily gestures, chosen words, silences, and the filmic general edited sequences, provide us spectators with poignant clarity regarding how pain had hit their bodies when the bullet hit the witnessed executed person. Additionally and no less importantly, the testimonies communicate how the conditions of the military occupation on the ground that pulled the trigger also made it difficult to communicate the pain of that experience outside the camp, by depriving them of audiovisual means of communication, and painting all the camp residents as unreliable speakers perforce who were responsible for their own suffering. When testifying in the film, the witnesses’ reenactments of the pain of witnessing destruction politicize their pain, framing it collectively and relationally—as impacting their bodies, as well as recovering by their very telling of their own stories of their embodied pain. In and by these reenactments of their absorption of the pain of the killed one, they transform from racialized and potentially targeted innate “terrorists” whose pain is their own fault to living martyrs—survivors who reclaim agency over their own becomings, personally and collectively. Arna’s Children extends this message by delving into the structure of feeling of living with potential death—of a beloved one, or one’s own—throughout life. The film traces how, even as children, the theater students lived with the encompassing threat of death under military occupation much before many of them died. The formative experience of knowing death intimately in life is not only a collective one but also one that challenges the temporal understanding of pain: rather than a past event, the pain of living with death is present and constant and projects onto the future, all at the same time.

“I Decided to Enter Jenin with a Film Camera”: Mohammad Bakri’s Journey to Jenin

Where is Mohammad Bakri coming from, when traveling to Jenin to film? What is the context begetting Bakri’s journey to Jenin in the first place? Such are the questions that Since You Left excavates. Addressing the heavy personal toll that Bakri had to endure after making Jenin Jenin, Bakri recounts the events that led to his portrayal as “a terrorist” in Israel, where he lives as a citizen and has been celebrated as an actor for decades. Since You Left demonstrates the escalation in inciteful discourse against ’48 Palestinian after 2000, when they were vehemently stigmatized as fifth-column and clandestine traitors.8 Yet this escalation marks the return of established racialized terms incriminating ’48 Palestinians as always already suspected traitors since the foundation of Israel. By reviewing the events that sent him to Jenin, Since You Left sheds light on the political conditions to which he and ’48 Palestinians at large are subjected to when depicted as the enemy from within, asserting that the making of the film did not simply invite an attack on Bakri but, rather, it was actually the position of ’48 Palestinians in Israel that enabled the attack on Bakri.

A valuable resource for assessing the rebuke inflicted on Bakri himself, Since You Left focuses on Jewish Israeli society’s demonization of Bakri after Jenin Jenin came out: it traces the changing esteem of the Palestinian public figure in Israel from a celebrated actor to a demeaned enemy. In Since You Left, actor Bakri’s will to become a documentary filmmaker and visibilize the witnesses of violence in Jenin disrupted the conditions of non-representability inflicted on Palestinians everywhere, and hence brought about the punishment: lumping Bakri in the category of “terrorists” typically ascribed to the Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza. This connection across historical Palestine, in and outside the Green Line, is important to Bakri, though in a different way. Since You Left resists the common naming of ’48 Palestinians as “Arab-Israelis,” which omits their affiliation to historical Palestine and dissociates them from the Palestinian struggle for self-determination. In the film, we see that any attempt of Palestinians to reclaim their identification as such in Israel endangers them. Tracing the occurrences of the early 2000s while paying particular attention to the circumstances informing the making and the reception of Jenin Jenin in Israel, Bakri employed a personal perspective to share his own experiences of these turbulent times in Since You Left. Bakri’s mode of the first-person singular develops as both a monologue as well as a dialogue: rather than informing the audience about the occurrences, Bakri communicates them to his late long-time mentor, the well-acclaimed Palestinian writer Emile Habibi. At the cemetery by Habibi’s grave, Bakri delves in an imaginary conversation with Habibi, recounting the latest events and recalling the times they spent together, as archival footage from both the near and far past inundate the screen. As the next few pages argue, Bakri attempted to follow the footsteps of Habibi and convey his message in creative manners to Jewish Israeli society. His role model and a citizen of Israel like him, Habibi wrote and directed the text for the play The Pessoptimist, in which Bakri starred.9 Since You Left focuses on the personal journey of the one who, through his winding ways from Israel to Palestine, from 1948 to 1967, leaves the profession of acting, dons the position of the writer and director, but is consequently and reluctantly deemed to dwell under the label of “a terrorist.”

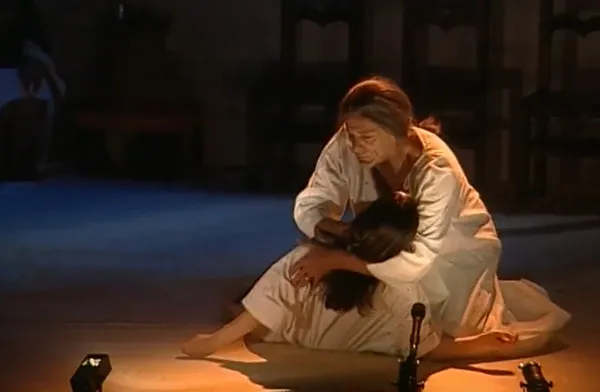

Bakri’s narration of the visit to Jenin in Since You Left begins in Israel, where “on the 29th of March 2002, at the night of the Seder, a young Palestinian from the West Bank entered the Park hotel in Netanya, and blew himself up. This was one of the most severe attacks,” Bakri explains. Consequently, “the attack gave the green light to Sharon’s government to declare war and re-occupy the West Bank.” Bakri’s decision to go film in Jenin thus follows on the heels of the IDF going to war. One central scene from Since You Left especially focuses on Bakri’s embarking on the road to Jenin—a road that begins in Nazareth. There, he and his colleagues at the El-Meidan theater participated in Federico Garcia Lorca’s play The House of Bernarda Alba. There, on stage playing Bernarda, Bakri acts “the part of a mean woman that beats her daughters”; together with Bakri, an actress named Valentina plays Adela, the youngest and most rebellious daughter of Bernarda. In this scene, immediately after showing Bernarda fervently pulling Adela’s hair and dragging her sideways on the stage, the film suddenly shifts to foreground an IDF tank driving through Jenin. In this way, images of a theater act merge and interchange with images from a war zone, while the figure of oppressive and violent Bernarda converses with that of an IDF soldier. Juxtaposing Bernarda’s staged figure played by Bakri with that of the IDF soldier, the figure of Adela played by Valentina accommodates an important role in this narration as well, especially in her suffering. As the tank completes its patrol, the frame returns to Bernarda, who first stands on top of her supinely dropped corpse, and then slowly bends toward her; Bakri’s voice simultaneously communicates that “we went, me and Valentina, my ‘daughter’ whose hair I tear, to a demonstration that took place north to Jenin, at the Jalame checkpoint.” Then, as footage from that demonstration inundates the screen, Bakri describes how “an Israeli soldier passed by us and began shooting at us. Valentina was hurt. She was standing beside me. And I went nuts.” Finally, while crying Bernarda slowly caresses her dead daughter Adela on stage, Bakri’s voiceover explains Valentina’s hurt to be the reason why he “decided to enter Jenin with the film camera.” Thus, whereas Bernarda the theatrical figure thrashes Adela, tacitly precipitates her suicide, and finally embraces her corpse, Bakri the filmmaker follows the wounds of actress Valentina as guiding footsteps leading his way to Jenin.

Directed and staged in various renditions, The House of Bernarda Alba traveled worldwide since the 1930s: accordingly, it is here possible to consider not only El-Meidan’s show but also Bakri’s directed scene discussed above, as one of these adaptations, though a unique one. When the repressive and oppressive power, embodied in the figure of the IDF soldier, again aggressively appears, Bakri decides to enter Jenin with his camera. Thus, Bakri utilizes and revises the play’s notions cinematically, expanding and literalizing Lorca’s attention to the means and mechanisms of artistic production and/as political predominance. Thus, while the IDF imposes its hurtful presence on the screen and on the body of the actress, Bakri aims to render the predominance of its power visible, both in this scene and also through his expressed plan to film in Jenin. In designing this scene through interpolations of soldiers’ images, and intending to direct Jenin Jenin, Bakri exposes, explicates, embodies, and mediates the implicit yet intrinsic connection between the ruler and the matriarch, structuring Lorca’s play. As soon as he gets off the stage, Bakri is interested in pulling the mask of acting off of his face and switching to stand behind the camera, so that he can see, hear, and audiovisualize the power apparatus that is actually running the whole show.