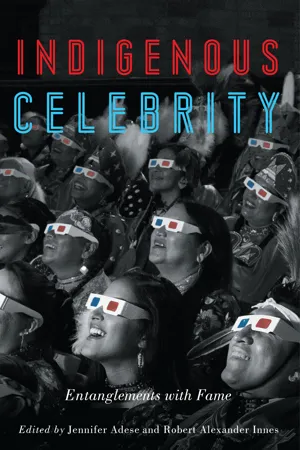

Indigenous Celebrity

Entanglements with Fame

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Indigenous Celebrity

Entanglements with Fame

About this book

Indigenous Celebrity speaks to the possibilities, challenges, and consequences of popular forms of recognition, critically recasting the lens through which we understand Indigenous people's entanglements with celebrity. It presents a wide range of essays that explore the theoretical, material, social, cultural, and political impacts of celebrity on and for Indigenous people.

It questions and critiques the whitestream concept of celebrity and the very juxtaposition of "Indigenous" and "celebrity" and casts a critical lens on celebrity culture's impact on Indigenous people. Indigenous people who willingly engage with celebrity culture, or are drawn up into it, enter into a complex terrain of social relations informed by layered dimensions of colonialism, racism, sexism, homophobia/transphobia, and classism. Yet this reductive framing of celebrity does not account for the ways that Indigenous people's own worldviews inform Indigenous engagement with celebrity culture––or rather, popular social and cultural forms of recognition.

Indigenous Celebrity reorients conversations on Indigenous celebrity towards understanding how Indigenous people draw from nation-specific processes of respect and recognition while at the same time navigating external assumptions and expectations. This collection examines the relationship of Indigenous people to the concept of celebrity in past, present, and ongoing contexts, identifying commonalities, tensions, and possibilities.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Table of contents

- Introduction: Indigeneity, Celebrity, and Fame: Accounting for Colonialism

- Chapter 1: Mino-Waawiindaganeziwin: What Does Indigenous Celebrity Mean within Anishinaabeg Contexts?

- Chapter 2: Empowering Voices from the Past: The Playing Experiences of Retired Pasifika Rugby League Athletes in Australia

- Chapter 3: My Mom, the “Military Mohawk Princess”: kahntinetha1 Horn through the Lens of Indigenous Female Celebrity

- Chapter 4: Indigenous Activism and Celebrity: Negotiating Access, Inclusion, and the Politics of Humility

- Chapter 5: Rags-to-Riches and Other Fairytales: Indigenous Celebrity in Australia 1950–80

- Chapter 6: “Pretty Boy” Trudeau Versus the “Algonquin Agitator”: Hitting the Ropes of Canadian Colonialist Masculinities

- Chapter 7: Famous “Last” Speakers: Celebrity and Erasure in Media Coverage of Indigenous Language Endangerment

- Chapter 8: Celebrity in Absentia: Situating the Indigenous People of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Indian Social Imaginary

- Chapter 9: Marvin Rainwater and “The Pale Faced Indian”: How Cover Songs Appropriated a Story of Cultural Appropriation

- Chapter 10: Collectivity as Indigenous Anti-Celebrity: Global Indigeneity and the Indigenous Rights Movement

- Chapter 11: Makings, Meanings, and Recognitions: The Stuff of Anishinaabe Stars

- Acknowledgements

- Selected Bibliography

- Contributors

- Index