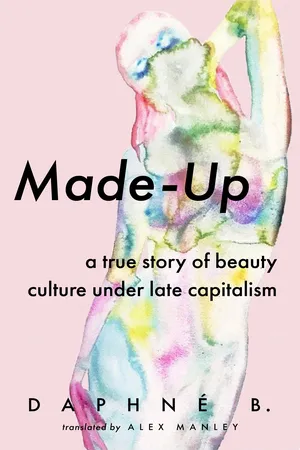

Made-Up

A True Story of Beauty Culture under Late Capitalism

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Made-Up

A True Story of Beauty Culture under Late Capitalism

About this book

SHORTLISTED FOR THE 2023 COLE FOUNDATION PRIZE FOR TRANSLATION

A nuanced, feminist, and deeply personal take on beauty culture and YouTube consumerism, in the tradition of Maggie Nelson’s Bluets

As Daphné B. obsessively watches YouTube makeup tutorials and haunts Sephora’s website, she’s increasingly troubled by the ways in which this obsession contradicts her anti-capitalist and intersectional feminist politics. In this poetic treatise, she rejects the false binaries of traditional beauty standards and delves into the celebrities and influencers, from Kylie to Grimes, and the poets and philosophers, from Anne Boyer to Audre Lorde, who have shaped the reflection she sees in the mirror. At once confessional and essayistic, Made-Up is a meditation on the makeup that colours, that obscures, that highlights who we are and who we wish we could be.

The original French-language edition was a cult hit in Quebec. Translated by Alex Manley—like Daphné, a Montreal poet and essayist—the book’s English-language text crackles with life, retaining the flair and verve of the original, and ensuring that a book on beauty is no less beautiful than its subject matter.

“The most radical book of 2020 talks about makeup. Radical in the intransigence with which Daphne B hunts down the parts of her imagination that capitalism has phagocytized. Radical also in its rejection of false binaries (the authentic and the fake, the futile and the essential) through the lens of which such a subject is generally considered. With the help of a heady combination of pop cultural criticism and autobiography, a poet scrutinizes her contradictions. They are also ours.” —Dominic Tardif, Le Devoir

“[Made-Up] is a delight. I read it in one go. And when, out of necessity, I had to put it down, it was with regret and with the feeling that I was giving up what could save me from a catastrophe.” —Laurence Fournier, Lettres Québécoises, five stars

"Made-Up is a radiant, shimmering blend of memoir and cultural criticism that uses beauty culture as an entry point to interrogating the ugly contradictions of late capitalism. In short, urgent chapters laced with humor and wide-ranging references, Daphné B. plumbs the depths of a rich topic that’s typically dismissed as shallow. I imagine her writing it in eye pencil, using makeup to tell the story of her life, as so many women do." —Amy Berkowitz, author of Tender Points

"A companion through the thicket of late stage capitalism, a lucid and poetic mirror for anyone whose image exists on a screen." —Rachel Kauder Nalebuff

"Made-Up is anything but—committed to the grit of our current realities, Daphné B directs her piercing eye on capitalism in an intimate portrayal of what it means to love, and how to paint ourselves in the process. Alex Manley has gifted English audiences with a nuanced translation of a critical feminist text, exploring love and make-up as a transformative social tool." —Sruti Islam

"The book will leave you both laughing in recognition and wincing at the reality of the beauty world’s impact on our collective psyche." —Chatelaine

"[Made-Up] examines the intersection of beauty culture and consumer culture... Aided by the work of writers like Anne Carson, Anne Boyer, Amanda Hess, and Arabelle Sicardi... B. makes sharp observations about the ideologies behind both beauty [...] and consumerism." —Bitch Media

"Made‑Up: A True Story of Beauty Culture under Late Capitalism is well worth reading." —Literary Review of Canada

"[Made-Up], newly translated by writer/poet Alex Manley from its original French, puts an intersectional, feminist lens on the author’s personal fascination with the makeup industry; it also reckons with the cultural dominance of this fascination as she aims to square anti-capitalist principles with beauty-product obsession." —BitchReads: 11 Books Feminists Should Read in September

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Tweleve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen

- Chapter Nineteen

- Chapter Twenty

- Chapter Twentyone

- Chapter Twentytwo

- Chapter Twentythree

- Chapter Twentyfour

- Chapter Twentyfive

- Chapter Twentysix

- Chapter Twentyseven

- Chapter Twentyeight

- Chapter Twentynine

- Chapter Thirty

- Chapter Thirtyone

- Chapter Thirtytwo

- Chapter Thirtythree

- Chapter Thirtyfour

- Chapter Thirtyfive

- Chapter Thirtysix

- Chapter Thirtyseven

- Chapter Thirtyeight

- Chapter Thirtynine

- Chapter Fourty

- Chapter Fourtyone

- Chapter Fourtytwo

- Chapter Fourtythree

- Chapter Fourtyfour

- Chapter Fourtyfive

- Chapter Fourtysix

- Chapter Fourtyseven

- Chapter Fourtyeight

- Chapter Fourtynine

- Chapter Fifty

- Chapter Fiftyone

- About the Author