![]()

CHAPTER 1 Love’s Warriors (August 382–January 378 BC)

Like many a traveler in modern Greece, George Ledwell Taylor carried with him a copy of Pausanias on June 3, 1818, when he rode out on horseback from the village of Lebadea. An Englishman on the grand tour, an architect with a special interest in antiquities, Taylor was looking for ancient Chaeronea, site of the most consequential battle fought on Greek soil. Three English friends and one Greek acquaintance accompanied Taylor. Suddenly his horse stumbled over a stone.

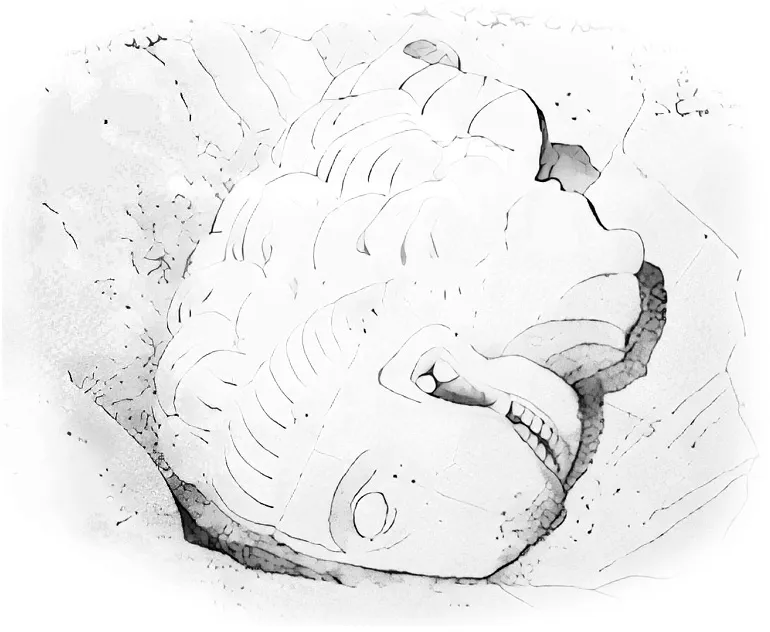

Taylor made this sketch of the lion’s head at Chaeronea before he and his friends had it reburied.

The stone had a curious, whitish appearance, so the party dismounted and started to dig, using their riding crops for lack of better tools. As they dug, one of the party read aloud from the notes they had copied the previous night out of Pausanias. In that ancient Greek travelogue, they had seen the following passage:

As one approaches Chaeronea, there is a tomb of the Thebans who died in the battle with Philip. No inscription adorns it, but a monument stands over it in the form of a lion, the best emblem of the spirit of those men. It seems to me the inscription is lacking because their fortunes were not equal to their courage.

Bit by bit, with the help of nearby “peasants” (as Taylor termed them), a giant carved stone was cleared from the soil. It was indeed the head of an enormous lion, nearly six feet high from the shoulder to the forehead, hollow yet weighing perhaps three tons. Several previous British travelers had searched for this statue in vain. Taylor’s horse and Pausanias’s text had led to the discovery of a lifetime.

“Their fortunes were not equal to their courage”: any British antiquarian knew what that meant. Ancient armies of enormous size had clashed at this spot, in 338 BC, and that of the Greeks had lost. The destiny of Hellas had changed forever; its city-states, small, independent units, had knuckled under to a single ruler, an imperious warrior-king. In their own eyes, their freedom had been lost. This lion was a signpost of defeat.

Unable to transport the huge stone fragments, Taylor simply had them reburied and went on his way. But they came to light again and were seen by other nineteenth-century tourists. Several noted that the pieces were large and could be reassembled with ease. There was talk of restoration, even offers from Britain to subsidize the project. These were rejected by the Greeks; the lion, after all, was a symbol of Hellenic resistance to foreign domination.

Local lore sprang up around the broken lion. It was said that during the Greek War of Independence, in the 1820s, a general had smashed the statue’s base, looking for treasure or weapons to fight the Turks. Inside, the legend went, he’d found a scroll with this mysterious sentence: “The lentils need some oil.” That showed, the rumors said, that the stonecutters who built this monument had not been adequately provisioned.

As the modern state of Greece connected to its past, the lion assumed new importance. In 1880, a sculptor was sent to Chaeronea, in hope that the lion could be reconstructed. Testing the firmness of the ground beneath, he found rows of skeletons, a few of which he removed for further study. An archaeologist, Panagiotis Stamatakis, was put in charge of excavating the site. Soon a startling set of finds was announced.

The lion had stood in the center of an enclosure formed by low stone walls, a rectangle seventy-four feet long and forty-four wide. Within that space, Stamatakis uncovered a polyandrion, or mass grave. Two hundred fifty-four men had been buried there in seven rows, as though formed up for combat in an infantry phalanx. Few weapons were found with them, but many strigils, metal scrapers for removing sweat and oil from the skin, and hundreds of tiny bone circles, apparently the eyelets from long-decayed sandals. A few ceramic cups had been buried there too, as though to nourish the dead in the afterlife.

The skeletons revealed the marks of violent deaths. One skull showed a laceration all across its forehead, suggesting the man’s face had been sheared clean off. Another bore a squarish hole where a sharp object had been driven into the brain. On shinbones and arm bones, gouges, grooves, and hacks spoke of the strokes of swords and spears. Clearly, these men had died amid the fury of all-out war.

The New York Times, on January 8, 1881, reported to the English-speaking world “the discovery of 260 corpses” at Chaeronea, then added a mysterious clause: “Some forty only of the glorious dead are missing.” The full complement, the Times implied, ought to have been three hundred. Already the remains had been linked to the Sacred Band, an elite corps of Theban infantry, three hundred strong, who died fighting at Chaeronea. Their valor, celebrated by ancient writers, seemed to be reflected in the marble lion—“the best emblem of the spirit of those men,” as Pausanias put it.

Ancient writers claimed the Band was destroyed to the last man, but the group in the grave, as the Times pointed out, was well shy of three hundred. That left room for doubt. With so few grave goods to go by and no inscription, the tomb’s occupants could not be identified with certainty. But over the decades, most scholars have agreed they are indeed the Sacred Band of Thebes.

A few pairs of skeletons were found with arms linked at the elbow, an intriguing arrangement given the nature of the Sacred Band. Ancient reports of the Band—largely accepted today, though occasionally doubted—say that it was composed of male couples, stationed in pairs such that each man fought beside his beloved. The erôs or passionate love they felt was a spur to their courage in battle, as each sought to excel in his partner’s eyes.

The story of this corps began exactly twenty-two hundred years before Taylor’s horse kicked that fateful stone. On a summer morning in 382 BC, in the city of Thebes, an episode unfolded that stunned the Greek world, all except those who had planned it. On that day a Spartan army seized control of Thebes in a sudden coup, setting off a forty-four-year chain of conflicts and struggles, of sporadic and futile attempts at peacemaking, and of power grabs by warlords with hired militias, leading finally to the decline and demise of the freedom of Greece.

That morning began the age of the Sacred Band.

It was a hot day. Thebes was in the midst of the Thesmophoria, a summer festival in honor of Demeter, goddess of grain and agriculture. The citadel called the Cadmea, the Theban acropolis, had been cleared of all men; only women could celebrate the secret rites or make offerings of phallus-shaped cakes, tokens of fertility, to the goddess. The governing council of Thebes, which normally met on the Cadmea, had to shift ground that day and meet in the marketplace, well below the fortified hilltop. This change of venue was crucial to what was about to take place.

Ismenias led the council that day, as he had for the past two decades. Thebes had changed course under his leadership, tilting away from Sparta, its long-standing ally, in the direction of Athens, its former foe. A cadre of young progressives had backed this policy shift, looking to Athens as the beacon of democracy and resenting Sparta, the reigning superpower, for bullying the Greeks. But others in Thebes despised this new alignment. These Laconists, as they were known, had gone along, grudgingly, as their city dealt insults and slights to the Spartans they favored.

One such insult was being delivered that very day. A Spartan army, commanded by a certain Phoibidas, was camped outside the walls, headed north to Olynthus, its apparent target. Olynthus had defied the terms of a Spartan-led treaty, and Sparta had declared war on behalf of the treaty’s signers, including Thebes. Troops had been requested from all quarters, but Thebes had forbidden its citizens to serve. Now that the enforcement squad was on their very doorstep, the Thebans continued to ignore it, but also made no effort to block its passage. Ismenias and his party might resent Spartan power, but they were not strong enough to challenge it—not yet.

Ismenias was one of three Theban polemarchs, magistrates who, by yearly election, were chosen to run the city. This triumvirate had, in recent years, been politically split. A staunch pro-Spartan, Leontiades, was also part of that board and had been since well before Ismenias came on the scene. Son of a Laconist father, grandson of a great war hero, this man had watched in dismay the rise of an opposition that leaned toward Athens. He did not like sharing power, especially when his own share was on the wane. He needed a bold stroke to regain control and bring Thebes back to the Spartan fold. So, with Spartan help, he’d devised one of history’s boldest.

By a prearranged plan, Phoibidas and his Spartans, in the plains outside Thebes, began marching off that morning, heading for Olynthus. Then around midday they turned and dashed toward a gate in the walls of Thebes. Leontiades was waiting there to admit them. He ushered the troops through streets made nearly empty by summer heat. Up they ran toward the Cadmea, a stronghold unguarded on this day alone. Once inside, they were handed a balanagra or “bolt puller”—a metal sleeve that slid over the bolt that secured the Cadmea’s gate, then caught it with a protruding stud and pulled it free. In modern terms, this was the key to the city. The Spartans cleared the women from the Cadmea, then locked themselves in and locked all opponents out.

The takeover happened so fast that, down in the lower city, the council meeting went on undisturbed in the market square. Suddenly Leontiades appeared to announce the change of regime. A few of his fellow Laconists had arrived shortly before and quietly stationed themselves—with armor and weapons—around the council venue.

“Do not despair that the Spartans have seized our acropolis,” Leontiades intoned, meaning the Cadmea. “They are enemies only to those who are eager to fight them.” Then he pointed to his rival Ismenias. “The law allows polemarchs to arrest anyone who does things that merit death. Therefore I arrest this man, on the grounds that he fomented war. You captains there, get up and seize him and take him away to the place we discussed.” Ismenias was led off to the Cadmea, now the headquarters of a Spartan army of occupation. Leontiades and his Laconist friends took control of Thebes.

Greek cities had known overthrows before, even covert troop insertions by “foreign” powers—that is, by other Greek cities. No previous coup had had such complete success. In only an hour or two, the new regime was installed, backed by an unassailable garrison force. Not a single blow had been struck.

The followers of Ismenias, those who’d “Atticized,” or sided with Athens, had suddenly become enemies of the state. Many made haste to flee, in a pattern seen often in Greek party strife: losing factions went into exile in cities that shared their views. In this case, Athens, the obvious place to seek refuge, could be reached by a two days’ walk or a single day’s ride. Three hundred Thebans made their way there, including Androclidas, a leading Atticizer who’d escaped arrest, the fate that awaited hundreds of his comrades.

Among these exiles was one whose name, though yet obscure, was soon to be heard everywhere. At around thirty years old, Pelopidas was among the youngest and most ardent of the group—a man of thumos, high-spirited anger and pride, as Plutarch termed him. Appalled by the Spartan seizure of his city, he longed to strike back, even if the effort took years—as indeed it would.

Messengers from the Spartans arrived at Athens, demanding Athenians banish the Theban exiles. To these envoys Athens turned a deaf ear. It welcomed the Thebans by official decree and made room for them amid its broad porticoes, bustling streets, and crowded agora, or marketplace. In those venues the exiles gathered and talked of events back home. Through friends and allies in Thebes, they kept a close eye on Leontiades—while he, as they would soon enough learn, was keeping an eye on them.

The Cadmea, the hill that now housed a force of fifteen hundred armed men, had been named for Cadmus, the mythic founder of Thebes. A prince of Phoenicia (in modern Lebanon), he had arrived in the region, according to legend, pursuing his sister Europa, abducted by Zeus. The oracle of Delphi told him to give up that quest and instead find a cow with moon-shaped marks on its flanks, follow its wanderings, and settle on the spot where it first lay down. That cow, called bous in Greek, led Cadmus to a region that then got the name it still bears today, Boeotia. Cadmus made his home where the cow took its rest and set in motion the tragic history of Thebes.

A nearby spring, the best source of water, was guarded by a dragon, so Cadmus slew the monster and planted its teeth in the ground. From those teeth sprang a crop of armed warriors, who fought one another until only five were left. (Some of the same teeth found their way to Colchis, land of the Golden Fleece, where they again sprouted armed men in the tale of Jason and the Argonauts.) Those five, the Spartoi or “sown men,” begot the lines of the leading families of Thebes. With the help of these dragon-teeth men, Cadmus built the enormous walls of the Cadmea and, at the top of the hill, a palace for himself.

Cadmus was now king of the land, and the gods gave him a queen, Harmonia, daughter of the adulterous union of Ares and Aphrodite. The Muses themselves sang the couple’s wedding hymn, at a spot later shown to tourists by Theban guides. But Harmonia brought a curse as her dowry. Aphrodite’s husband, the blacksmith god Hephaestus, hated the offspring of his wife’s love affair. He crafted a charmed necklace for Harmonia’s wedding gift that would bring youth and beauty, but also dreadful misfortune, to those who owned it.

This necklace would pass through the hands of generations of Theban rulers, enacting its doom on each in turn. The sufferings of this royal line became famous throughout Greece. Their horrific fates were staged, over and over, in tragedies composed by playwrights in classical Athens. Thanks to the survival of those plays, the myths of Thebes still claim a place in our collective consciousness.

The necklace passed first to Semele, daughter of Cadmus and Harmonia, a beautiful young woman whom Zeus took to bed. Semele conceived a child by Zeus, but after jealous Hera planted doubts in her mind, she worried that her “divine” lover was only an ordinary man. She demanded that Zeus appear to her in his true form, and the god obliged by descending as a thunderbolt—instantly scorching her to death. Her fetal child was rescued from the ashes and sewn into Zeus’s thigh. It matured there into Dionysus, a god who was thus, in a sense, born at Thebes. Euripides opened his play The Bacchae with the return of Dionysus to his native city, where his mother’s grave was still smoldering, many years later.

Next the necklace came to Agave, Semele’s sister, whose son, Pentheus, had come to the throne of Thebes. The Bacchae tells the story of this wretched pair, aunt and cousin, respectively, to the god Dionysus. Though Agave believed her sister’s son had been fathered by Zeus, Pentheus scoffed, declaring that Semele had only invented the tale to explain her pregnancy. Dionysus was determined to prove his divinity. Working a spell on both Agave a...