- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Bible claims that God's sovereignty is absolute and that humans make their own choices. Christensen explains two harmonizing views—Arminian and Calvinistic—making a fresh, biblical case for Calvinism's.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access What about Free Will? by Scott Christensen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Road Map for Libertarianism

Walk down Main Street and conduct an informal survey: “Do you believe in free will?” The answer is axiomatic: “Of course; who doesn’t?” The rich and the poor, the schooled and the unschooled, the famous and the forgotten, the pretty and the pedestrian—nearly everybody believes in the freedom of choice.

But what does this really mean?

The default answer usually lies along the lines of what is commonly known as libertarianism. The word sounds delightful, enlightening, positively liberating. But how many know what it means? What does this elusive ideology about the human will espouse?

Mapping the Debate over Free Will

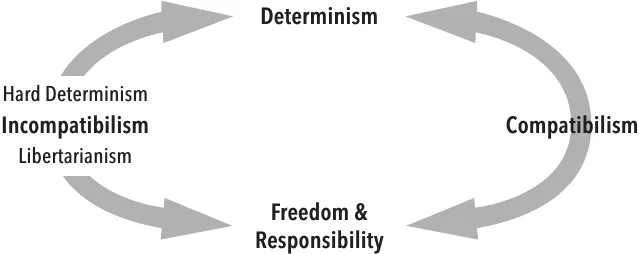

In order to answer that question, we need to unfold a bigger map of the debate over free will (see fig. 1.1 below). Libertarianism falls within a broader landscape of ideas about freedom and determinism. These ideas can be categorized as incompatibilist and compatibilist theories.1 Incompatibilist theories state that freedom and responsibility are incompatible with determinism. Determinism refers to the idea that all things that occur in our world are necessarily and causally determined by prior conditions. Thus, given specific prior conditions, only one outcome could possibly take place. We live in a cause-effect universe. This is particularly true in the natural world. Gravity causes apples to fall. The right combination of oxygen, fuel, and heat causes fires. When the temperature cools to 32 degrees Fahrenheit, it causes water to freeze.

Few people deny that the natural world follows this strict cause-effect principle.2 But when it comes to human choosing, there is not so much agreement. In this case, many accept that the act of choosing isn’t part of the material world of natural laws. This is true of both libertarians and compatibilists. We should interject here that the sort of determinism that Calvinists hold to is not a physical determinism because God is not a physical being. Furthermore, all Christians hold that our thoughts, beliefs, feelings, conscience, imagination, and so forth reside in the immaterial realm. This comports with Scripture, which speaks of the souls or spirits of persons as being distinct from their material bodies (1 Thess. 5:23). For the Christian, to be “away from the body” is to be “at home with the Lord” (2 Cor. 5:8; cf. 1 Cor. 5:3). At the resurrection, our bodies will be rejoined with our spirits. Accordingly, the act of choosing is not the result of material processes, as a materialist or naturalist might conclude.

Now, among these incompatibilist theories are hard determinism and libertarianism. Hard determinism holds that human choices are causally determined but incompatible with human freedom and responsibility, which are regarded as illusions. Secular hard determinists (including some materialists) hold that human choices are the result of environmental factors, genetics, brain chemistry, psychological and social conditioning, and so forth.3 Conversely, libertarianism holds that humans must be free and responsible, which means that our choices cannot be causally determined by forces outside our own control. Libertarianism denies determinism (i.e., choices are indeterministic). See fig. 1.1.

Fig. 1.1. Incompatibilist and Compatibilist Theories of Free Will

This, then, leaves us with the compatibilist theory, which states that determinism is compatible with human freedom and responsibility. Sometimes compatibilism is called soft determinism, in contrast to hard determinism. In this regard, both hard determinism and soft determinism are deterministic theories, while libertarianism is an indeterministic theory. Human moral responsibility is a matter that virtually all Christians have affirmed and that the Bible clearly teaches. Furthermore, both libertarians and compatibilists would agree that some kind of freedom is necessary in order for human responsibility to make sense. Christian brands of hard determinism affirm human responsibility but reject human freedom. Very few Christians have explicitly embraced this perspective, but some of its thinking creeps into otherwise inconsistent beliefs.4

While libertarians and compatibilists agree on the necessity of human freedom, they have fundamental differences about what sort of freedom is necessary for human responsibility. Furthermore, while both Arminians (who are libertarians) and Calvinists (who are compatibilists) affirm the sovereignty of God, they differ in how God exercises his sovereignty in the providential governance of the world. Calvinists believe that God causally determines all that transpires in the world, whereas Arminians believe that God’s providence does not employ causal determinism except in rare cases.

With the scope of the debate set forth, let us now focus our attention on libertarianism. This model of human freedom embraces many nuances, and philosophers advance sophisticated arguments in support of it. Furthermore, not all libertarians agree on the particulars. I will not canvass the thicket of these differences.5 Rather, I will seek to lay out the basic parameters of what the majority of libertarians hold to—particularly Christian libertarians, who are generally Arminians. Reduced to its core, this concept of free will teaches two fundamental ideas.

Contrary Choice

First, libertarianism teaches that humans are fully capable of making choices contrary to the choices they actually make. This is called the power of contrary choice. Arminian theologian Roger Olson declares, “Free agency is the ability to do other than what one in fact does.”6 Norman Geisler states that morally free creatures are able to respond in more than one way in a given situation: “When we did evil we could have not done it.”7 Good and evil are both fair game, and each alternative makes itself an equal-opportunity employer for the liberated will.

A person can choose to do what he wants to do, but he can equally choose to do what he doesn’t want to do. Little Jimmy really doesn’t want to eat his broccoli, but he can also choose to go against this prevailing desire and eat it anyway. Libertarianism is far less concerned than compatibilism about the specific reasons why Jimmy makes one choice over another. Libertarianism prefers to focus on the rainbow of options in the pantry of human choices. It champions one’s power to explore any color he chooses and its multiple variations without being hampered by particular prevailing reasons.

My brother-in-law’s family lived in New Zealand for a time. What a life of limitations. When you go to the store in New Zealand to buy shampoo, you don’t have long aisles of options to choose from. Selecting shampoo is made simple. By virtue of its extremely narrow options, your purchase is virtually determined for you already. If you like freedom of choice, you don’t live in New Zealand; you live in America.

You want to buy shampoo? What kind? Aveda or Aveeno? Maybe Nexxus or Neutrogena will suit you? If not, try Pert or Pantene. The options are bewildering by design, and you get to choose whatever you like—or don’t like. That is the triumph of libertarian free will.

Self-Determining Choice

Second, libertarianism teaches that when we have the ability to make alternative choices, they cannot be determined by anything outside the person making those choices. “The essence of this view is that a free action is one that does not have a sufficient condition or cause prior to its occurrence.”8 Olson states that free will is the power of self-determining choice and that “it is incompatible with determination of any kind.” This idea amounts “to belief in an uncaused effect—the free choice of the self to be or do something without antecedent.”9 In other words, a self-determining choice is not sufficiently caused by anything prior to the agent who makes a choice. Each person is the “unmoved mover”10 who alone puts his choices in motion. We might say that he is the first cause (originator) of his own actions.11

It is important to note that libertarians don’t deny that reasons stand behind our choices. Many things can influence those choices, including both internal and external conditions. For example, we have internal beliefs, values, desires, preferences, motivations, and any number of odd inclinations that can influence the choices we make.12 But in the end, our strength of will has an unequaled power to overrule all our inner dispositions. Jacob Arminius observed that humanity enjoys “a freedom from necessity, whether this proceeds from an external cause compelling, or from a nature inwardly determining absolutely to one thing.”13

As strong as Jimmy’s hatred for broccoli is, in the end that hatred cannot be said to determine his refusal to eat the dreaded vegetable. He could act against this most powerful desire, slaying it like a dragon, and devour the broccoli with defiance—if he chooses to do so. Thus, human freedom is a fiercely independent enterprise. If Jimmy chooses to eat the broccoli that he doesn’t want to eat, his decision isn’t determined by anything other than the power and freedom of Jimmy’s own will.

We are also affected by external conditions, such as our upbringing, our education, people who exert psychological power, favorable or unfavorable circumstances, rules or laws to govern behavior, persuasive arguments in defense of a particular choice, the lure of the culture, and so forth. While all these internal and external influences can serve as reasons for the choices we make, libertarianism states that no particular reason or set of reasons is sufficient to determine our choices. Libertarian Bruce Reichenbach notes, “Freedom is not the absence of influences, either external or internal,” but “we can still act contrary to those dispositions and choose not to follow their leading.”14 In most cases, compelling reasons might appeal to a person, who then chooses to follow its leading. What cannot happen is that a set of reasons becomes “strong enough to move the [person] decisively to choose one thing over another. Even if a person agrees in light of various reasons and arguments presented that one course of action is preferable, that in no way guarantees that it must be followed.”15 Free will means that we always have alternative choices at our disposal and that we exercise complete control over which alternative we choose. Christian libertarians believe that God endows his creatures with this freedom and that he steadfastly refuses to interfere with it except in rare cases.

It is important to note that many libertarians distinguish between reasons and causes. We can have reasons for the choices we make, but those reasons cannot be causal in nature.16 In either case, if a libertarian agrees that reasons can be construed as causes, we can still act contrary to any such causes. Furthermore, if libertarians maintain that desires, pr...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Free-Will Problem

- 1. A Road Map for Libertarianism

- 2. Assessing the Whys of Libertarianism

- 3. How Big Is Your God?

- 4. A Road Map for Compatibilism

- 5. A Dual Explanation for Why Good Stuff Happens

- 6. A Dual Explanation for Why Bad Stuff Happens

- 7. To Be Free or Not to Be Free

- 8. Why We Do the Things We Do

- 9. A Tale of Two Natures

- 10. Exploring Corridors

- 11. Navigating the New Nature

- 12. Absolute Freedom

- Appendix 1: Comparing Libertarian and Compatibilist Beliefs on Free Agency

- Appendix 2: A Review of Randy Alcorn's hand in Hand: The Beauty of God's Sovereignty and Meaningful Human Choice

- Glossary

- Select Bibliography

- Index of Scripture

- Index of Subjects and Names