eBook - ePub

Beyond the Ninety-Five Theses

Martin Luther's Life, Thought, and Lasting Legacy

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the context of the Reformation's 500th anniversary, Nichols overviews Luther's life and theology and guides readers through his major written works (including an annotated Ninety-Five Theses), sermons, and hymns.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Beyond the Ninety-Five Theses by Stephen J. Nichols in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

LUTHER, A LIFE

MARTIN LUTHER lived an eventful life; consequently, the question of what to leave out becomes every Luther biographer’s major challenge. With only two chapters specifically devoted to biography, we especially face that challenge. Nevertheless, I have attempted to address the crucial events in Luther’s life. These incidents, explored in chapter 1, include such pivotal moments as the vow made during the thunderstorm that sent him to the monastery, the posting of the Ninety-Five Theses that catapulted him to the very center of everyone’s attention in 1517, and the Reformation discovery of justification by faith that “opened the very gates of paradise” for him and that became the fundamental message of all he preached. This chapter ends with Luther’s bold stand before the Diet of Worms and then describes his “kidnapping.”

In the next chapter, we pick up the story as Luther returns from his exile at the Wartburg Castle. The events unfolding during these later years include the marriage of this former monk to a former nun, the establishment of the first parsonage in the modern age, the decisive meeting with theologian Ulrich Zwingli at Marburg, and the tireless commitment to establishing the newly formed church. Through studying the events of both his early and later years, we begin to understand why Luther figures so prominently in the pages of history, and why he continues to fascinate readers five centuries after his death.

1

THE EARLY YEARS

1483–1521

“If there is any sense remaining of Christian civilization in the West, this man Luther in no small measure deserves the credit.”

Roland Bainton

Roland Bainton

“Martin Luther the Reformer is one of the most extraordinary persons in history and has left a deeper impression of his presence in the modern world than any other except Columbus.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson

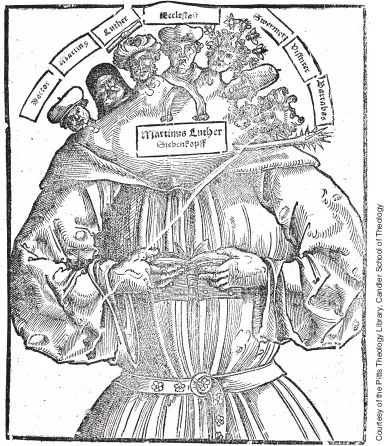

IN I529 JOHANNES COCHLAEUS authored a tract vilifying Martin Luther. Entitled the “Seven-Headed Luther,” the piece featured a woodcut on the title page caricaturing Luther as a dangerously conflicted individual who, according to the writer, threatened great harm to the church through his varied and contradictory personalities. One portrayal depicts Luther as a madman with bees encircling his head. The final woodcut depicts him as Barabbas, implying no less than the charge that he was the very enemy of Christ. Pope Leo X, who originally viewed Luther’s antics as nothing more than the ravings of a drunken German, portrayed Luther as the archenemy of the church, and he succeeded in rallying both church and empire against the German monk. Even at Luther’s death many wondered about his true legacy. Was he an instrument of God? Or, was he a tool in the hands of the devil?

One thing on which scholars agree is that the world “Martin Luder” was born into on November 10, 1483, was quite different from the one he left on February 18, 1546. The decades of his life contained unprecedented change and upheaval, and Martin Luther was at the center of it all. Luther, however, experienced quite modest beginnings for such an enduringly prominent figure in Western history. As he wrote in his old age, “I come from a family of peasants.” In fact, he continued:

Fig. 1.1 Timeline: Early Years

| 1483 | Born on November 10 in Eisleben |

| 1492–98 | Attends school at Mansfield, Magdeburg, and Eisenach |

| 1501–05 | Attends University of Erfurt; receives B.A. (1502), M.A. (1505) |

| 1505 | Makes vow during thunderstorm, July 2. Enters monastery |

| 1507 | Is ordained |

| 1509 | Receives B.A. in Bible. Begins lecturing at Erfurt on the arts |

| 1510 | Makes pilgrimage to Rome |

| 1511 | Enters Black Cloister, Augustinian Monastery at Wittenberg |

| 1512 | Receives doctorate in theology. Appointed to faculty of theology at Wittenberg |

| 1513–17 | Lectures on Psalms, Romans, Galatians, and Hebrews |

| 1517 | Posts Ninety-Five Theses on church door on October 31 |

| 1518 | Debates Cajetan at Augsburg |

| 1518–19 | Possible date for Reformation breakthrough (or 1515–16) |

| 1519 | Debates Eck at Leipzig |

| 1520 | Writes Three Treatises |

| 1520 | Receives Papal Bull |

| 1521 | Appears at Diet of Worms on April 16–18 |

| 1521 | Is placed under the Imperial Ban and condemned as a heretic and outlaw in May |

| 1521 | Goes into “exile” at Wartburg Castle |

Who would have divined that I would receive a Bachelor’s and then a Master’s of Arts, then lay aside my brown student’s cap and leave it to others in order to become monk, thereby of course earning for myself such shame so that my father was bitterly displeased; and that despite all I would get in the Pope’s hair—and he in mine—and take a runaway nun for my wife? Who would have predicted this for me?

Luther’s Early Education

Few would have predicted the outcome of Luther’s life, especially his parents. Hans and Margeret Luder moved from Eisleben, Germany, the place of Luther’s birth and baptism, to Mansfield in Luther’s first year. At Mansfield, Hans continued his work as a miner, overseeing two smelting furnaces, painstakingly providing for young Martin’s education. Instead of working as a young boy, the lot of most peasant youth, Luther attended school where he studied Latin, elementary grammar, and the essentials of a religious education—the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer, and the children’s creeds. Here he opted for the Latinized version of his name, Luther, instead of the German, Luder. When Luther turned fourteen, his parents sent him to continue his education at the monastery in Magdeburg. This monastery fell under the jurisdiction of the Brethren of the Common Life order, known for its piety, and counting among its members Thomas á Kempis, the author of the devotional classic The Imitation of Christ. Magdeburg was a highly respected school and, consequently, very expensive. The Luther family’s modest income barely funded Martin’s first year, so, like the other peasant students, he took to begging in the street for his bread. “Panem propter Deum,” bread for God’s sake, rolled off Luther’s tongue often as he begged along the streets of Magdeburg.

The next year Luther continued his studies at Eisenach. Presumably, Eisenach appealed to Luther for both academic and financial reasons. Luther’s mother had relatives nearby who undoubtedly offered some relief, as well as occasional meals. It was, however, an elderly town lady who, admiring Luther’s abilities and resolve, took special care of him. Even with this help, Luther’s time at Eisenach was a struggle. Despite these challenges, he excelled in his studies, rising to the head of the class. His achievements allowed him to move on to Erfurt where he could study law to fulfill his parents’ dream for their son’s life. Through entering a noble profession, his parents hoped he would escape the peasant class and bring honor and status to the family name. At Erfurt, he received his Bachelor’s degree in 1502, and his Master’s in 1505. Both were to prepare him for further study of the law and a doctorate in jurisprudence.

I Will Become a Monk

Studying at Erfurt was a turning point in Luther’s life on many levels. On his daily walk, he encountered a sculpture that often captured his thoughts. The image depicts Christ as judge with a sword clenched between his teeth and a piercing stare. This image, not only in medieval renderings of Christ, haunted Luther for years as he contemplated his guilt before God. A particular German word helps us understand the true impact of this image on Luther’s life: anfechtung. Translated as “crisis” or “struggle,” in Luther’s case it is best described as an intense spiritual struggle and a crisis. In fact, it is better to use the word in the plural, anfechtungen, for in reality a series of spiritual crises marked Luther’s early life of study.

After completing his M.A. in January 1505, Luther remained at Erfurt to receive specialized training in law. He excelled in the legal field and was well on his way to fulfilling his father’s wish. In June of that year, he made a trip home to Mansfield. On his return to Erfurt Luther was caught in a violent thunderstorm. He was paralyzed by the storm and attached great spiritual significance to it, and in utter fear he believed God had unleashed the very thunder of heaven to judge his soul. In total desperation he cried out to St. Anne, the patron saint of miners: “Help me, St. Anne, and I will become a monk.” The date was July 2, 1505. Exactly two weeks later, Luther threw a party for his classmates, giving them his law books and his master’s cap and withdrawing from his doctoral studies. Then he told them that on the following day he would enter the monastery.

1.2 Not all responses to Luther were favorable. This depiction of Luther as a seven-headed monster graces the title page of Johannes Cochlaeus’s 1529 book criticizing Luther.

Luther desired his father’s blessing for exchanging the master’s cap for the monk’s tunic; the blessing, however, did not come. As Luther records, “When I became a monk, my father almost went out of his mind. He was all upset and refused to give me his permission.” Later, in 1521, Luther apologized for disobeying his parents in his dedicatory letter to On Monastic Vows, addressed to his father. Fifteen years before the book, and despite his parents’ refusal, Luther entered the monastery. All candidates were accepted on probation for one year’s time. During this time, as a “novice,” Luther threw himself into the rigors of monastic life and completed his year of probation. He took the monk’s habit in 1506 during a ceremony which culminated in Luther’s prostrating himself before the abbot. Ironically this was over the very slab that covered the grave of a principal accuser of reformer John Hus. And on the slab was that haunting image of Christ as judge. His parents did not respond to the invitation to attend the ceremony. Luther hoped that by entering the monastery he would resolve his spiritual crises. In reality, however, it only fueled them. One year after his vow to St. Anne, Luther was abandoned by his family, and he also acutely felt abandoned by God.

In later years, Luther reflected back on his life as a monk: “I myself was a monk for twenty years. I tortured myself with praying, fasting, keeping vigils, and freezing—the cold alone was enough to kill me—and I inflicted upon myself such pain as I would never inflict again, even if I could.” In fact, Luther carried out his duties with such rigor that he exclaimed, “If any monk ever got to heaven by monkery, then I should have made it. All my monastery companions who knew me can testify to that.” He concludes his reminiscing by noting that “if it had lasted much longer, I would have killed myself with vigils, praying, reading, and the other labors.” But, there was still no resolution to his spiritual crises.

As the first decade of the sixteenth century came to a close, two occurrences profoundly impacted the young monk and set him on a course that would revolutionize the church. His prior, or superior, at Erfurt often expressed to the abbott, Johann von Staupitz, his exasperation with young Martin Luther. Staupitz, though confounded by Luther’s spiritual struggles, recognized the young man’s intellectual abilities and promise. He ordered Luther transferred to the monastery at Wittenberg. Just a few years earlier, Staupitz and others founded the University at Wittenberg. Frederick the Wise spared no expense in making his new university rival the already established universities covering German lands and beyond. He wanted the best and brightest faculty, and he wholeheartedly approved of the choice of Luther. Luther’s training, however, was not in Bible and theology; consequently, before he began his career as a lecturer in Bible and theology, he once again became a student. While studying at Wittenberg, he lectured on both the arts and Aristotle. Staupitz hoped that the mental occupations of academia would crowd out Luther’s many internal struggles. He was wrong.

Luther began his second set of degrees, taking another B.A. in Bible in 1509. He was then sent back to Erfurt to be a lecturer. While there, the monastery at Erfurt needed to send some documents to Rome. Staupitz viewed this request as an opportunity for Luther to make his peace with God, believing the Holy City would do his soul much good. Luther and another monk embarked on their pilgrimage to Rome in 1510, traveling the same route as thousands of monks over the centuries of the medieval era. Anticipating a spiritual paradise, Luther instead discovered something much more akin to John Bunyan’s “Vanity Fair” in Pilgrim’s Progress. “When I first saw Rome,” he recalls, “I fell to the ground, lifted my hands, and said, Hail to thee, O Holy Rome.” That impression quickly dissolved, however. He continues, “No one can imagine the knavery, the horrible sinfulness and debauchery that are rampant in Rome.” As he climbed up and down the stairs of Pontius Pilate, reciting the Lord’s Prayer on each step, his disillusionment only increased. By the time he reached the top, he exclaimed, “Who knows if this is true?”

The trip to Rome failed to quell the storms of Luther’s soul. On one occasion, after his return, Luther met up with Staupitz in the garden at the Wittenberg cloister. Staupitz did not understand why Luther could not comprehend God’s love for him. “Love God?” Luther retorted, “I can’t love God, I hate him.” Staupitz had no solution for the young man, other than to order him to pursue a doctorate in theology. Again, he argued that studying the church fathers and the medieval tradition would end his fight with God. In 1512, Luther received his doctorate, not in his originally intended course of l...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Martin Luther’s Legacy

- Part One: Luther, a Life

- Part Two: Luther, the Reformer

- Part Three: Luther, the Pastor

- Part Four: Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses

- A Brief Guide to Books by and about Martin Luther

- Bibliography

- Index of Persons

- Index of Luther’s Works

- Index of Scripture