- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Afghanistan in the Cinema

About this book

In this timely critical introduction to the representation of Afghanistan in film, Mark Graham examines the often surprising combination of propaganda and poetry in films made in Hollywood and the East. Through the lenses of postcolonial theory and historical reassessment, Graham analyzes what these films say about Afghanistan, Islam, and the West and argues that they are integral tools for forming discourse on Afghanistan, a means for understanding and avoiding past mistakes, and symbols of the country's shaky but promising future. Thoughtfully addressing many of the misperceptions about Afghanistan perpetuated in the West, Afghanistan in the Cinema incorporates incisive analysis of the market factors, funding sources, and political agendas that have shaped the films.

The book considers a range of films, beginning with the 1970s epics The Man Who Would Become King and The Horsemen and following the shifts in representation of the Muslim world during the Russian War in films such as The Beast and Rambo III. Graham then moves on to Taliban-era films such as Kandahar, Osama, and Ellipsis, the first Afghan film directed by a woman. Lastly, the book discusses imperialist nostalgia in films such as Charlie Wilson's War and destabilizing visions represented in contemporary works such as The Kite Runner.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Afghanistan in the Cinema by Mark Graham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

Imperialist Nostalgia

1 Getting in Touch with Our Inner Savage

Before the 1970s, Afghanistan did not exist in the cinematic dreamworld of the West. Afghans featured briefly in lowbrow “Rule Britannia” films like King of the Khyber Rifles (1953) and Carry On . . . Up the Khyber (1968), but Afghanistan itself did not become the subject of a Western feature film until John Frankenheimer’s The Horsemen (1971). Scripted by Academy Award winner Dalton Trumbo, The Horsemen was the first (and only) twentieth-century American feature film ever to be shot in Afghanistan itself, with the cooperation of Afghan Films, the national production company. At the time that Frankenheimer was making his picture, President Richard Nixon was abandoning Afghanistan to increased Soviet patronage, paving the way for an eventual coup that led to the Russian invasion of 1979. The film thus stands as a poignant relic of an Afghanistan at the twilight of its innocence—before the seizure of power by Daoud Khan, before Nur Muhammad Taraki, before the Soviets, before the horror.

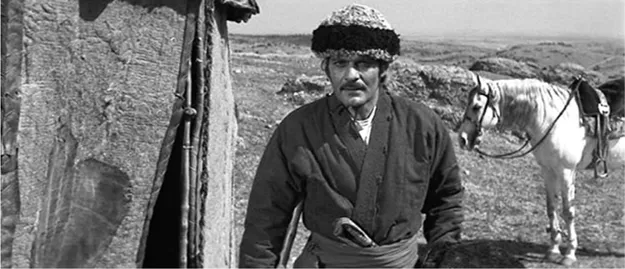

The Vanishing Afghan: Uraz (Omar Sharif) prepares to ride into the sunset.

Based on a novel by French author Joseph Kessel, The Horsemen tells the story of the proud and ambitious Uraz, who seeks to eclipse his father Tursen’s legendary prowess in buzkashi, the Afghan national pastime. In this game that one commentator has called a “cross between dirty polo and open rioting,” riders struggle to transport the buz, a headless goat or calf carcass stuffed with sand (and weighing close to a hundred pounds), around a post a mile away and return to the game’s starting point and goal, the “circle of justice.”1 When Uraz the young chapandaz (master player of buzkashi) fails to win the championship game in Kabul, he embarks on a perilous journey back to his home. Along the way, his servant Mukhi and Zereh, a beautiful and independent Kuchi nomad woman, scheme to kill him and steal his prize horse, Jahil. The redoubtable Uraz holds them off, even after a village doctor amputates his fractured and infected leg. Devastated with the thought that he might never ride again, the chapandaz hides the secret even from his own father until the climax, when he and Jahil are reunited in a masterful display of horsemanship.

In evoking this rough and rugged story, The Horsemen clearly aspires to a documentary way of seeing. The issue of authenticity was a crucial one for the director: “Was this an accurate picture of what life is like in Afghanistan? Yes! Life is like this in Afghanistan, exactly the way I depicted it. I spent a lot of time there, I saw a lot there, but this was a story that I loved reading. I identified completely with that character.”2 On location in Kabul, Frankenheimer made a point to highlight the ethnographic, filming an array of barbers, dyers, bakers of naan, blacksmiths, and snake charmers. Evocative juxtapositions abound: automobile traffic interspersed with donkeys, Mercedes sedans with women in purple chadaris.3 There are mosques and minarets and a muezzin calling to the heights where the camera floats, observing both the pristine Kabul River and the traffic coursing beside it. Frankenheimer sees Afghanistan with an almost childlike wonder and depth of feeling, conscious of having gone where no one had gone before, at least in the American cinema.

Despite his claim of having “been there” sufficiently long to portray the “real” Afghanistan with exactitude, Frankenheimer, like every other traveler, has packed some ideological baggage to take with him on his excursion into the unknown. Thus he transitions easily from talking about Afghanistan as a place to enjoying it as “a story.” As Steven H. Clark has written, “[T]he appeal to the testimony of the eyewitness itself may be deconstructed into an illusion of an experiential present embedded in a commentary that necessarily exceeds and transgresses those criteria of authenticity. Seeing presupposes believing.”4 But what exactly is it that Frankenheimer sees (and believes)? Nothing less than a cinematic vision of an almost prehistoric, uncorrupted world—what the director himself called “the most beautiful country I’ve ever seen.”5

That almost preternatural beauty is the focus of a series of majestic establishing shots at the beginning of the film. Vast desert wastes of ice appear, so terrifyingly raw and jagged that they look as if they have stood unchanged since the world began. They soon give way, in a startling juxtaposition, to dusty steppes and deserts, cerulean lakes, and irrigated fields that glitter like tesserae in a gentle plain of unremitting green. In such a place, men can be men again and cling to ancient codes both “bold and barbaric” as the film’s trailer puts it. One such man appears astride his horse, a rifle slung across his shoulder, a living icon perched atop the Khyber Pass of our dreams. For a brief moment, the viewer could be forgiven for believing that the frontier has not disappeared, that a lost world lingers on the edge of ours, a savage haven for the self to rediscover what it has surrendered to modernity.

The film’s sublime landscape effortlessly evokes Albert Bierstadt’s nineteenth-century paintings of Yosemite. Both portray an untouched reserve of primitive Eden, a fountain of spiritual youth that Manifest Destiny had placed in our hot and eager hands. Encountering the massive scale of the American continent had all the trappings of a religious experience. This idea of the romantic sublime inspired Thomas Gray to say of the Chartreuse Mountains in 1739: “Not a precipice, not a torrent, not a cliff but is pregnant with religion and poetry.”6 The vast power and presence of nature lies at the very heart of romantic mythology, a stand-in for medieval faith eclipsed by Enlightenment rationality. Into the natural world the romantics projected their need for a primeval place of origins, a sacred space that could act as foil to the deceitful and alienating labyrinths of self and city that characterized the modern metropolis. While the tropes stayed more or less the same from one continent to the next, there were a few local variations. Europeans had their Alps and Roman ruins, Americans had the frontier.

The fantasy of the Wild West so well known today was already being mass-produced by late-nineteenth-century pop culture. Thanks to the likes of Ned Buntline, Buffalo Bill Cody, and Owen Wister, Americans came to imagine a pristine and uninhabited wilderness lying on the rim of their democratic experiment. Like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who described the Alps as “abysses beside me to make me afraid,”7 the West for Americans was a boundary that was both terrifying as well as self-affirming. But where European travelers would face down their existential dread by taking a hike in the mountains, most Americans encountered the sublime with the sole intent of slaughtering and dominating it.

Crossing the Atlantic, the romantic quest transformed into what Richard Slotkin has called a “regeneration through violence,” by which the American national consciousness could define itself by a struggle against the forces of wilderness and savagery. The outcome was Manifest Destiny but required a dangerous yet necessary association with the very forces against which American civilization arrayed itself. Only by merging into the regenerative chaos of Western wilderness could America as a nation be born.8

While such sentiments circulated for many centuries in captivity tales and dime novels before the advent of cinema, the Western genre provided the most visceral and epic expressions of this myth of conquest, transmuting genocide into nation building by producing “an Other whose destruction is not only assured but justified.”9 This narrative became increasingly persistent with the rise of American preeminence following World War II. Not coincidentally, Westerns as a genre in film reached their apex in the 1950s, their popularity paralleling America’s self-consciousness as civilizing agent and superpower. The Horsemen came at the tail end of this trend, with its native hero struggling to live his traditional way of life. That these traditions are doomed to fall before the onslaught of civilization is a given, as it is in most other Westerns that long for a return to the primitive. Thus when the film shows jets streaming overhead, interrupting Tursen’s speech to his chapandaz, it recalls an identical scene in Lonely Are the Brave (1962), also scripted by Dalton Trumbo.10 In this earlier film, a lone cowboy rides across an iconic Western landscape only to have the vision shattered by some fighter planes streaking across the sky. The only difference between the two stories is that in Afghanistan the Indians, rather than the cowboys, are the heroes.

Like the imagined Wild West, The Horsemen represents nature as a kind of social Darwinist paradise: a vicious interspecies battle for power and survival with the strong always coming out on top. The film features many scenes of animals viciously attacking each other, from partridge and camel fights to furious head-butting rams. But more than anything, it is the violence of buzkashi (literally “goat pulling”) that transforms the film’s ideology into visual spectacle. Under Frankenheimer’s direction and Claude Renoir’s masterful cinematography, the sport becomes positively iconic. At the time of the film’s release, film critic Roger Ebert glowingly wrote, “There hasn’t been a sustained action sequence on this scale since the chariot race in Ben-Hur.”11 The costumes of the chapandaz are authentic in every detail, and in the remarkable eleven-minute buzkashi sequence, it is mostly real chapandaz who play the game, no holds barred. Frankenheimer even went so far as to hire Habib, one of Afghanistan’s most famous buzkashi players, to serve as technical advisor as well as appear in the sequence itself.12

Only just two years before filming, Frankenheimer later recalled, the Afghan government had outlawed the use of knives during play.13 Whips, however, were still used to devastating effect on competing riders (and still are), resulting in routine bruises, lacerations, and broken bones. For some, the final outcome can be death. Toward the end of the match, a brief shot catches a dead horse being dragged from the field by a very modern tow truck and crane. Animals were very visibly harmed in this production because that’s what happens in Afghanistan on the mythic frontier, where violence inextricably binds both men and beasts.

Strong-willed humans like Uraz inhabit that bestial space with animal combatants, defying the forces of nature and time. “They ride today as if it were still yesterday,” the film’s trailer boldly proclaims, “as though there were no tomorrow. They ride with a savage frenzy that defies our civilization. They live by a code as bold and barbaric as the ancient game they play.” Frankenheimer likewise asserted in an interview that, “Afghanistan itself has not changed in over a thousand years.”14

The trailer’s ballyhoo falls squarely within a long-established mode of representing the developing world. Despite the seemingly authoritative medium of the camera, many critics have uncovered the ways in which documentary films and photographic journalism can construct a vision of the globe that reinforces a naturalized hierarchy between civilized and savage, modern and traditional, the West and everywhere else. In step with many other mainstream sources of ethnography (such as National Geographic), The Horsemen revels in exotic dress and ritual, noble and virile savages, the identification of America with the modern future, and the rest of the world with the prehistoric past.

These noble savages are the sole inhabitants of The Horsemen’s dreamscape. Happily they little resemble those Afghan buffoons and treacherous zealots of earlier “Rule Britannia” films. Instead they serve heroically to uphold an admirable and ancient patriarchal social code. They have no need for anything other than their horses, their honor, and their buzkashi.

This representation of the native other also differs from those one could see in contemporary revisionist Westerns like Little Big Man or A Man Called Horse (both 1970). In these films, despite their sympathetic depiction of the Lakota people, the white man remains the locus of agency as well as of the drama itself. Through his eyes, the culture of the Native Americans continues to be interpreted and evaluated. In The Horsemen, on the other hand, Afghans act autonomously in an indigenous social and cultural space that the film represents as meaningful and attractive. By doing so, Frankenheimer takes the logic of revisionist Westerns one step further, dispensing with the white mediator in order to more perfectly immerse the civilized audience into savage spectacle.

Astride his beloved Jahil, the white stallion so reminiscent of the Lone Ranger’s Silver, Uraz evokes all too clearly the lone rider of the western frontier, displaced now in the Afghan landscape. The noble savage par excellence, this premodern Übermensch spends much of the narrative asserting his God-given right to be the alpha male. He and his fellow Afghans synthesize the two archetypal Western characters: cowboy and Indian. They even look like a strange fusion of the two with their knee-high leather boots, long cloaks, and distinctively Asian features. As a result, Uraz unites in one person the American self and its Asian other—not the Asia against which Americans were fighting at the time, but the comfortable and colorful barbarism of travelogue and frontier mythology.

The first time Uraz appears on-screen, he is watching a gruesome and all-too-real camel fight on which he has bet a respectable number of afghanis. The horseman’s isolated presence fills most of the frame, thrown in relief by the background with all its distant little men who hustle and bustle meaninglessly. Not caring if he wins or loses, Uraz represents the quintessential aristocrat, a man who was born to ride, born to win, and born to lead, elevated from the masses by an innate master morality that would make Friedrich Nietzsche envious.15

As the savage par excellence, Uraz displays not only heroism but also a propensity for ignorance and cruelty. After tumbling off his horse in Kabul, he clings to the superstitious belief that pages from the Qur’an can disinfect and heal his gashed leg. He deliberately baits his faithful servant Mukhi, inciting him to steal the horse and slay him in the mountain passes of the ancient road. Similarly he toys with Zereh’s attraction to him, at first spurning her advances because she is “untouchable” (a concept well known in Hinduism but foreign to Islam), and then trying rape her.16 This cruelty, paradoxically, appears to be a by-product of his rebellion against tribalism and against the father whose fame and power he covets. If Uraz embodies certain admirable savage principles, he lives by others that are pathologically antisocial, even sociopathic. This ambiguity lies at the heart of his character as well as the ways in which Westerners have traditionally viewed the Islamic world: as a place where men can be real men but at the same time can thus indulge in excesses that horrify even as they titillate.

For the Western viewer of The Horsemen, Uraz thus facilitates communication between a civilized consciousness and the inner primitive in a dream of unrestrained power. Such a process had become all the more pertinent at the time of the film’s release in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Haunted Eyes

- Part 1: Imperialist Nostalgia

- Part 2: The Burqa Films

- Part 3: Border Crossings

- Conclusion: Ending Charlie Wilson’s War

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author